The Battle for the International Hotel

Historical Essay

by James Sobredo

The International Hotel at 848 Kearny Street at Jackson, 1978.

Photo: courtesy Nina Serrano

| The International Hotel’s brick face and leftist politics earned it the nickname of the “Red Block.” In the late 1960’s, new development projects threatened this home of primarily Filipinos in San Francisco’s Manilatown. Feeling drawn to defend this cultural landmark and the rights of Filipinos, UC Berkeley students and activists joined with I-Hotel residents to resist. In San Francisco history, the Battle for the International Hotel marks a moment of solidarity to preserve culture and the right to the city in the face of new urban development. |

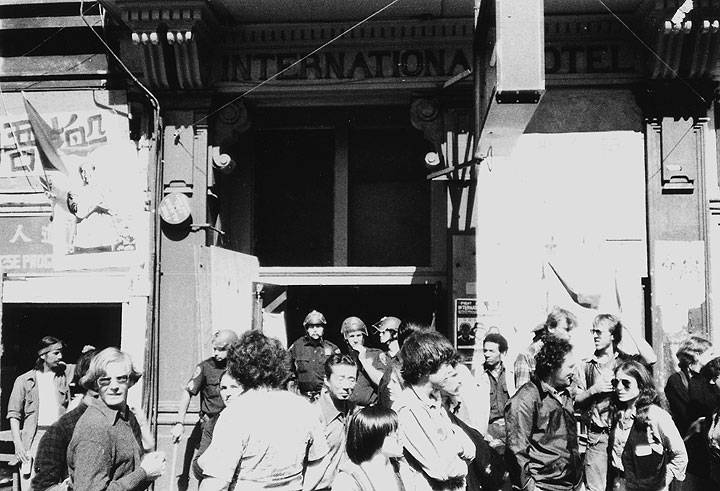

A face-off at the I-Hotel, 1970s.

Photo by Eddie Foronda

At the very heart of Manilatown was the International Hotel, a three-story, red-brick building at 848 Kearny Street at the corner of Jackson. In the 1970s it also became the most famous residence of Filipinos. The I-Hotel symbolized the Filipino American struggle for identity, self-determination, and civil rights. It was a struggle that involved not only Filipinos but other Asian Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, student activists, religious groups and organizations, gays and lesbians, leftists, and community activists.

The eviction was part of a larger development project occurring in the Bay Area. As early as 1946, corporate organizations proposed ambitious urban development projects: organizations such as the Bay Area Council proposed the Bay Area Rapid Transit system, and the San Francisco Planning and Housing Association proposed neighborhood urban renewal by eliminating urban blight in the Western Division. (Mollenkopf 1983, pp 159-160) Other proposals included building the Golden Gateway project, a series of freeways intersecting through San Francisco -- a project rejected by the City -- and the Yerba Buena Center project, which, when completed, also displaced thousands of residents from South of Market. By the late 1960s, as part of this Manhattanization of San Francisco, the expanding financial district was encroaching on Manilatown and neighboring Chinatown. In the autumn of 1968, Milton Meyer and Company, which owned the hotel, started sending eviction notices to the tenants of the I-Hotel. "To my mind," explained Walter Shorenstein, chairman of Milton Meyer, "I was getting rid of a slum." (Calvin Trillin, U.S. Journal: San Francisco, Some Thoughts on the International Hotel Controversy, The New Yorker, December 19, 1977) In response, the tenants organized the United Filipino Association (UFA) to battle the eviction.

Photo by Chris Huie

Among the earliest Filipino activists working with the I-Hotel was Violeta Marasigan, then a recent graduate of San Francisco State College who was hired as a social worker by the UFA as part of their Multi-Service Center: "When I started working with the old men, I saw that they were discriminated against in terms of their access to social services. A lot of them had been here for over 30 years, but they could still barely speak English or write. These manongs were mostly single retired farmworkers and seamen living on social security retirement benefits." Marasigan, known as Bullet X to her friends, discovered that they were not receiving their full benefits. At that time, when the SSI benefits were around $200 a month for the maximum, Filipinos were only getting around $90 to around $130, recalled Marasigan. None of the Filipinos knew that they were not getting the full benefits due to them. Marasigan accompanied the Filipinos to the SSI office and spoke with their caseworkers. After that, everybody had their full SSI benefits.

The late sixties were the height of the anti-war movement and Third World student strikes at San Francisco State and UC Berkeley. Student activists became among the strongest supporters of the I-Hotel.

Housing protesters at City Hall, 1977.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

Emile De Guzman, a young Filipino student leader of the 1969 Third World Strike at Berkeley, had been working with Pete Velasco, Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and other Filipino members of the United Farmworkers Union in Delano. Born and raised in San Francisco, De Guzman grew up visiting Manilatown with his father. When he heard about the eviction notices and the subsequent fire that killed three hotel tenants, he rallied other Berkeley students to protest the eviction: "I got really involved in the I-Hotel and organized students to go down there and picket outside Walter Shorenstein's office."

The International Hotel Tenants Association (ITHA) eventually replaced the UFA, and Filipino student activists like De Guzman assumed the leadership. It was through a coalition of students, tenants, and community activists that the ITHA was able to sign a three-year lease and avoid eviction. In order to avoid further public criticism of his role in the eviction, Shorenstein would sell the hotel to the Four Seas Investment Corporation, a Hong Kong-based company that planned to demolish the building and replace it with further commercial development: an underground parking garage.

August 5, 1977, the day after the eviction of the I-Hotel.

Photo: Jesse Drew

It was not just Filipinos, however, who got involved in the I-Hotel struggle. Jean Ishibashi, a third-generation Japanese American born in Chicago, was pregnant at the time but still came to the I-Hotel protests. "For many decades, I carried my family's unspoken anger from eviction and internment," said Ishibashi. "When I learned that elderly Asians who were my father's age were being evicted, I identified with them, and that's why I showed up." For Ishibashi, the I-Hotel symbolized a time when the Asian American community as a whole came together. It was mostly, however, the more progressive and left-leaning members of Asian America.

Protest at City Hall during final months before eviction, 1977.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

Elderly Chinese also resided in the I-Hotel. The Asian Community Center and the Chinese Progressive Association were located in the I-Hotel. Both organizations strongly supported mainland China and Chairman Mao Zedong's Communist government, and this conflicted with the Chinatown leadership, who supported the Koumintang Government (KMT) in Taiwan. This was also part of the continuing attacks against the I-Hotel, said De Guzman. The Chinese leftist organizations would always show a lot of films about China.

Not surprisingly, Filipino activists at the I-Hotel shared the same political leanings as their Chinese neighbors. During that time, Joe Diones was the manager of the I-Hotel, said Marasigan, herself an anti-martial law activist who would later be imprisoned by Marcos. He was a very good manager, you see, but he was also a card-bearing member of the Communist Party of the USA. The leftist Kalayan newspaper was also published at the I-Hotel, and its members would go on to form the Katipunan ng mga Demoratikong Pilipino (KDP), which became the largest Filipino socialist organization in America. With its left-leaning management and tenants, the red brick building quickly became known as the Red Block.

African Americans and whites were among the supporters of the I-Hotel. The Rev. Jim Jones of the infamous People's Temple church brought members of his congregation, mostly elderly African Americans, to the protests.

The reverends Cecil Williams (Glide Church) and Jim Jones (People's Temple) at an anti-eviction rally at the I-Hotel, January 1977.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

Members of the Peoples' Temple at the anti-eviction rally January 1977.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

“We even had a terrorist group that supported the I-Hotel,” recalled the poet Al Robles. The Weathermen group planted a bomb at the Herbst Theater, and they went on radio and said, We did this because the I-Hotel was being oppressed. The bomb did not explode, but upon hearing the news at the time, Robles looked out an I-Hotel window, saw hundreds of people marching and chanting, and said, “We don’t even know who these guys are. What kind of manongs are these?”

Joe Diones looks out the window of the I-Hotel at 848 Kearny Street.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

The I-Hotel also became a bastion of Asian American cultural expression. Formed by Asian Americans from the Bay Area, the Kearny Street Workshop (KSW) had an office at the first floor of the Hotel. Luis Syquia, a poet and activist of the I-Hotel struggles, explains, “The main focus, rationale, and philosophy behind the Kearny Street Workshop was to really reflect the communities that we came from, and also to contribute to those communities through our art.” KSW brought together Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and Korean artists and writers into one community. Rejecting the idea of art for art's sake, Luis believed that art was always a tool for social change. Among some of KSW's members were artist Jim Dong, playwrights Lane Nishikawa and Norman Jayo, photographers Crystal Huie and Leny Limjoco, silk-screen artists Leland Wong and Nancy Hom (KSWs current director), and poets Al Robles, George Leong, Doug Yamamoto, Genny Lim, Russell Leong, and Jeff Tagami and Shirley Ancheta.

For Manilatown and its Filipino residents, the I-Hotel represented a life and community. Explained Robles, the unofficial Zen Master of the Filipino community, “The I-Hotel was the life of the manongs, the life of the Filipinos. It was their heart, it was their poetry, it was their song. Robles, whose poetry was recently collected in Rappin' with 10,000 Carabaos in the Dark elaborated: "It wasn't only a hotel: it was a gathering place that brought them together. It was celebration; it was ritual. It was bringing back a life."

—James Sobredo, excerpted from "From Manila Bay to Daly City: Filipinos in San Francisco" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, and Culture, A City Lights Anthology, 1998

Protesters at an anti-eviction rally in January 1977.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

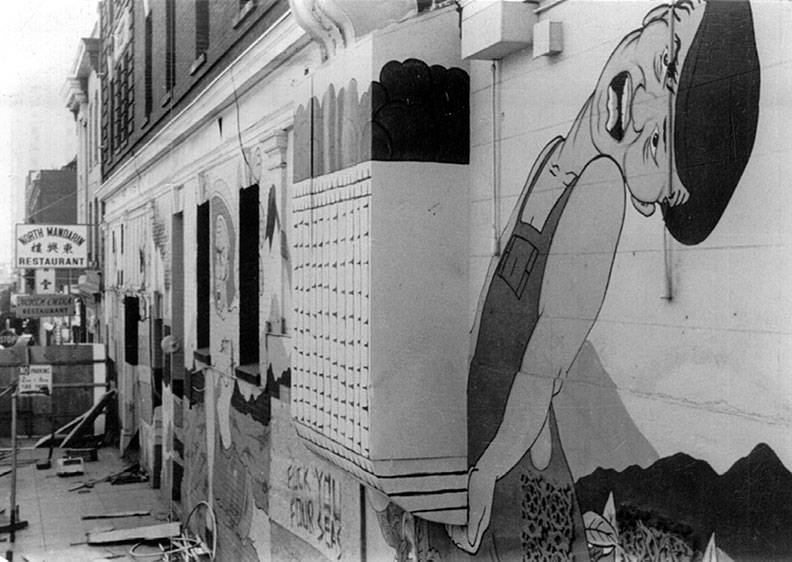

Non-permissional art comments on the I-Hotel hole, sitting empty for 25 years after the eviction.

Photo: D.S. Black