GEORGE STERLING

Historical Essay

by Jim Fisher

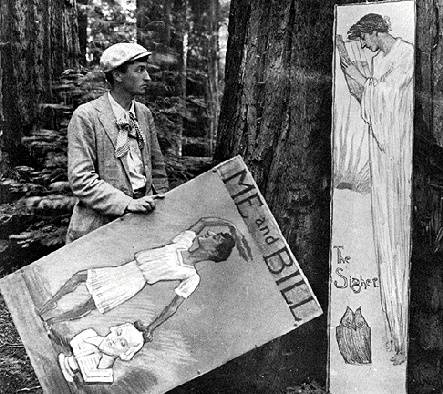

George Sterling prepares for the performance of The Triumph of Bohemia at the Bohemian Grove, Sonoma County, c. 1907

photo: City Lights Books, San Francisco, CA

Though once hailed by Ambrose Bierce as the future "poet of the skies, prophet of the suns," the San Francisco poet George Sterling is no longer read, even locally. Yet among California writers and poets, a peculiar affection still remains for the original Poet Laureate of San Francisco, despite his being remembered more for his personality than for his verse.

A recent tour of local bookstores, including several regional collections, turned up a single out-of-print play at a price only curators would consider. It is an interesting position: to have become, in the words of Kevin Starr, "tragically passé," yet to have the few books you did publish sell at prices that rival your most successful contemporaries. For a person who was compared to Spenser, Milton and Keats during his lifetime, the hype is not all that surprising.

Despite his modest poetic talent, Sterling was a truly charismatic figure, able to charm artists and patrons alike. This, combined with backing by Ambrose Bierce, a manic ambition, and (it didn't hurt) a classical aquiline profile, quickly established him as a poet of great promise. Nicknamed "The Greek" by his friend Jack London, he frequently appeared decorated with laurels at the Bohemian Club's yearly Russian River festivals -- christened 'Midsummer Jinks' -- for which he was soon composing grove plays, including The Triumph of Bohemia and A Forest Play. It was these plays that were later anthologized, becoming the novelty pieces now occasionally found in city bookstores at appropriately decadent prices.

Virtually every literary circle in the Bay Area between 1895 and 1925 could count Sterling a member, if not a congregating force. The Piedmont crowd, which included Jimmy Hopper, Jack London, Jim Whitaker, Blanche Partington, Xavier Martinez and Austin Lewis, knew the Sterlings' villa as their most popular meeting site. After Sterling and his wife Carolyn moved to Carmel in 1905— initially to escape the social distractions of the city—the artists and writers followed. By 1907 a colony had formed, with Sterling again playing host, his plans for writing vanishing in favor of seaside abalone hunts and evenings of performance, recitation and consumption. An austere Upton Sinclair, who joined the colony in 1909 expecting to find an industrious group of fellow socialists, was so taken aback by what he deemed dissipation that he left after three months.

Photographs of the period were very often group shots, with Sterling and his entourage sporting clubs, Greek gowns, and other fanciful costumes; or fantasy portraits, such as one of the critic Porter Garnett, naked except for artificial horns and a goatee, squatting on a hillside at one of the Bohemian Jinks. Although there is strong possibility that "[Sterling] had portraits taken of himself in the nude or near-nude, striking classical stances," (Starr, p.277) the closest we have is Sterling in a grove of redwoods, posing before two oversize paintings of himself in a toga, his hand on a bust of William Shakespeare.

It was arguably this flirtation with symbolic roles that gave the bohemians, and George Sterling in particular, their contemporary attraction. Unfortunately, the bohemians themselves were not always up to the symbolic roles they elected to assume. After the identities were hastily affirmed by a community impatient to recognize its great minds, many artists came to believe the illusion of their audience, with the predictable relaxation of output.

It wasn't that George Sterling was fundamentally misguided, or that his enthusiastic group of followers lacked sustainable talents, but the enchantment of California, and especially San Francisco, seemed to tempt artists into premature self-congratulation. As Kevin Starr observes:

San Francisco's isolation might give rise to a splendid originality, but it could also lead to narcissism and a self-justifying tolerance for the third-rate the soothing critical climate, as well as the sunshine, was in danger of filling up San Francisco with poseurs, unchallenged by circumstances of discernment. Bohemia often concealed a colossal idleness. (Starr, p.260)

Although there were certainly exceptions--Mary Austin for example, continued to produce plays, anthropological studies, and novels until late in life-- individuals of the period had a tendency to concentrate on the social aspects of being writers and artists to the detriment of their work.

At Coppa's, the bohemian rendezvous on the famed Montgomery Block in San Francisco, Sterling's lines, "the blue-eyed vampire, sated at her feast / Smiles bloodily against the leprous moon" were inscribed on the wall-length mural, his name beside such immortals as Dante, Goethe and Rabelais. In the same restaurant, writer Isabel Fraser is said to have mounted a ladder and been christened "Queen of Bohemia" to the applause of the assembled "Coppans."

In time, one could find the names, quotes or sketches of most notable local artists on the wall alongside the acknowledged masters. One quote was by Nora May French, a flamboyant journalist and poet, who once remarked famously over lunch, "I have an idea that all sensible people will ultimately be damned." It turned out to be a prophetic statement. One year after the 1906 earthquake destroyed Coppa's and its ambitious mural, Nora May French swallowed poison at Carmel-by-the-Sea, beginning a trend of self-destruction among the bohemian generation.

Sterling himself was the culmination of the trend, and his suicide by ingestion of cyanide in 1926 was perhaps the archetypal response to the city's turn-of-the-century bohemianism. As the unofficial Poet Laureate of San Francisco, Sterling was visible, social, yet discreetly dissolute. To many he embodied the heart of the Bay Area literary scene, and his death, the final and most publicized suicide associated with the San Francisco art scene, lent a grim legitimacy to the fate of his precursors, including: Nora May French (cyanide, 1907); Jack London (morphine, 1916); Carolyn Sterling (cyanide, 1918); David Lezinsky (gunshot, 1921); Richard Reaf (poison, 1922); and Herman Sheffauer (defenestration, 1926).

Nonetheless, in San Francisco today, the myth of Sterling still survives. In Golden Gate Park, the city maintains a George Sterling Glade. And Robinson Jeffers, the great Californian poet who took up residence in Carmel after the colony disbanded, called Sterling "the sweetest voice of the iron age," composing a memorial poem and prose retrospective on his death. For William Everson, another influential California poet, Sterling possessed something of "the accessibility of a saint," arguing that "despite the record, one ventures to believe him a truly beautiful spirit." (Everson, 63-4)

Although he may have fallen short of his poetic goals, Sterling was by all reports sincere in his efforts to represent a regional identity. In a young city "ever unsure of its exact relationship to the great world," (Starr, p.254) he was willing to risk a dynamic aesthetic role. That one was due is perhaps no better demonstrated than by how readily, if precipitously, the community claimed him as their own and glorified his accomplishments.

FURTHER READING:

Everson, William. Archetype West. Oyez Press, 1976.

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence and Nancy Peters. Literary San Francisco. Harper and Row, 1980.

Garnett, Porter. The Bohemian Jinks, A Treatise. San Francisco, 1908.

Gullette, Alan. A George Sterling Page.

Saunders, Richard. Ambrose Bierce: The Making of a Misanthrope. Chronicle Books, 1985.

Starr, Kevin. Americans and the California Dream 1850-1915. Oxford University Press, 1973.

Walker, Franklin. The Seacoast of Bohemia, an Account of Early Carmel. San Francisco, 1966.