Reflections on the End of Community Memory

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

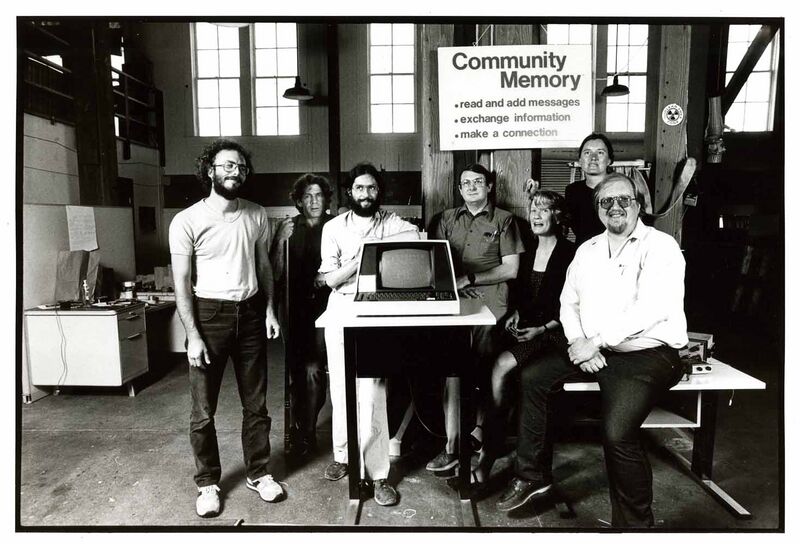

Staffers of Community Memory, early 1980s (Lee Felsenstein in darker shirt in middle under sign).

Courtesy Computer History Museum

One important change we wanted to effect with Community Memory was “demystification of computer technology,”—counteracting the tendency of the general public to draw away from computer equipment based on the industry’s propaganda aimed to create fear and awe of the technology. (The early use of the term “giant brains” is a good example, implying that the hulking computer was capable of superhuman thought when in fact it had to be large because it was capable of such puny “thought”.)

Unfortunately, some computer-adepts would unconsciously play that card—often, I believe, out of an inability to relate to non-adepts. Many of our cohort had taken refuge in learning the technology in place of learning basic social skills, and their clumsy efforts to bridge the gap and inspire awe instead exacerbated their relational shortcomings.

We knew we had to expend effort to minimize that gap by combatting the general public's tendency to think that our product was only for “computer people.” This was an ongoing issue throughout the generations of Community Memory design. We were apparently reasonably successful, as shown by the bystander’s comment I overheard while preparing to perform maintenance on one of our second-generation terminals—“That’s the people’s computer.” The only vandalism at any of our installations took place when we had shut down the system and left a useless terminal exposed.

We had also to break through the assumption that ordinary people had to be prevented from using computer equipment. When we installed our first teleprinter terminal without advance notice in the Berkeley record store, the general response to our five-second pitch to people walking toward it (“would you like to use our electronic bulletin board? We’re using a computer”) was “Oh—can I use it?” It was important that the sound-suppressing cover on the terminal had hand openings offering immediate access.

We emblazoned the terminal’s cardboard housing with informal lettering, posted a hand-drawn set of posters with instructions in psychedelic script and cartoons, and programmed the system to spring to life after a period of disuse by printing “Touch me! Type a word and press the green button.” (Pressing the green carriage return without entering a word elicited a brief set of instructions.)

Perhaps most important in breaking down the invisible barrier was the location. The record store terminal was directly in front of a physical bulletin board used heavily by musicians. While we didn’t do a study, it certainly appeared that many who used the bulletin board came over to the terminal. I was attending the terminal when a fellow in full hippie regalia whose mind seemed not to be on this planet approached, ignored my pitch, and performed what appeared to be a very effective search, leaving with a printout to drum up some business making music. However, when we moved the terminal from that location it became apparent that the musician’s traffic did not follow.

For the first generation, from August 1973 to December 1974, our primary concerns were finding ways to enhance the search methodology beyond asking the user to imagine what words might have been attached as index words as others entered an item. We made weekly printouts of database segments and placed them at the terminals as a “digest” for people to peruse. Our analysis showed a very broad spread of index words, leading us to think of ways to cluster them so that a search on one word would yield a result of more than one item. This led to further experimentation during the second version, which lasted from 1984 to 1989.

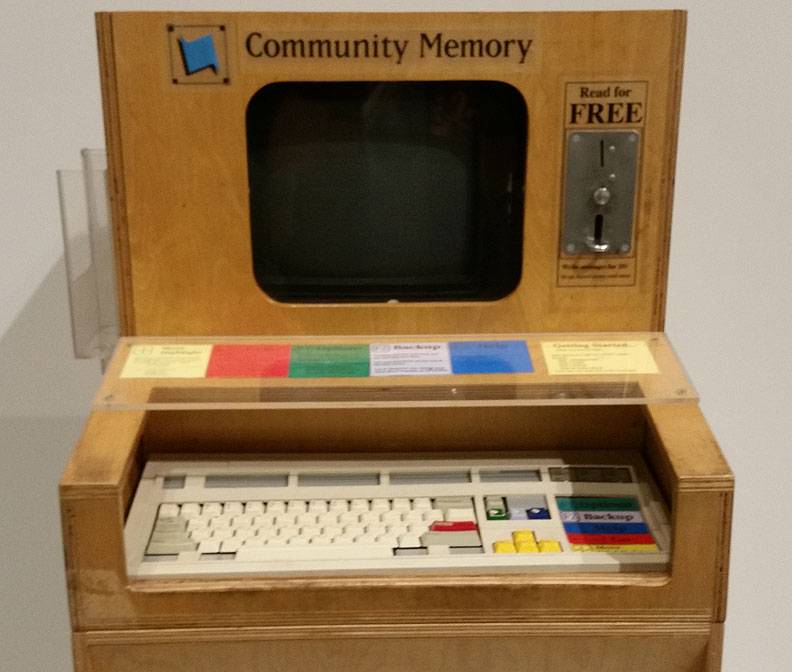

During that second version we began to encounter “spamming” and “flaming” by high school age kids who flooded their items with index words (leading us to impose a limit), and who entered items with zero useful content but loaded with rhetoric, bragging, and offensive language that might be expected of unsupervised adolescents. This occasioned our decision to add a coinbox as a small obstacle to promiscuous entries while keeping searches free. It was physically implemented in our third version but never turned on.

During the third version (1990–1992) the issue of speech conflict began to arise. In a few instances users contacted us demanding removal of items mentioning them. We worked to mediate the conflicts with only fair success and the issue eventually became moot when we closed the system down due to loss of funding from a state grant.

The spread of personal computers led to a growing request from users to have a dial-in capacity, and we developed a “Dial-Up” disc for generic IBM-compatibles that would work, but this came into conflict with one of my basic principles. It was a long-term belief of mine that we should not allow connection of external computer equipment to the system, on the grounds that it would give the owners of that equipment advantages over the general usership.

Close-up of 1990s Community Memory kiosk.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

By 1992 the prevalence of individually-owned computers was nothing like today—they were distinctly associated with a stratum of people who could be distinguished by their technical skill level and their identification with the larger computer industry’s membership. “Computer People” would describe them. Opening the floodgates to them would have resulted in social fragmentation and the likely prospect of loss of walk-up traffic. The possibility of “going commercial” and opening the system to online users while collecting fees was one solution to our financial problem that loomed ahead.

The messy prospect of imposing a system of resolving conflicts and avoiding legal liability for users’ speech was something that we could no longer evade if we “went commercial”. We had not made much progress on that aspect. These issues contributed to my decision to shut down Community Memory when funding ran out in 1992. My own shaky finances had been resolved by my employment at Interval Research, which would take me away from CM at a time when we had lost many of our employees. We would have required a significant amount of capital to tide us over into profitability—capital that was unavailable due to the lack of models on which to base projections.

Community Memory thus predated the commercialization of social media with its attendant problems. We did provide a proof of concept given that the concept was limited to feasibility in the social domain. This could easily be ignored by deflecting attention to the volunteer bulletin board system (BBS) experience along with The WELL, which opened in 1985 and grew to survive for decades, eventually bought out by its users in 2012, and continuing to this day. Its parent company attempted to set up many similar systems, but all of them failed to survive. While Community Memory did not become hegemonic like the giants of social media today, the environment of today is in no way comparable to that of the 1970s and 1980s, and we were not about to change our purpose from expanding the possibilities for community to fattening our investors’ bank accounts.

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns

Lee Felsenstein (b. 1945) is an electronic design engineer who designed several early personal computer devices and who created the first public-access social media system. A veteran of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964, he embarked on a process of exploration of media intending to develop technology to enable the creation of communities. In 1970 he determined that this technology would be a network of computers, and in 1973 his project opened the first computer bulletin board for public use—Community Memory.

Realizing that personal computers would be necessary for a public system, Lee did some of the first design work on personal computers more than a year before the first personal computer was announced. He designed several of the first generation of personal computer products, including the first video text generator for personal computers, and the first successful portable computer.

He has been named a Fellow of the Computer History Museum (2016) in recognition of his pioneering efforts and continues his efforts at developing community-enabling designs.