Homebrew Computer Club

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

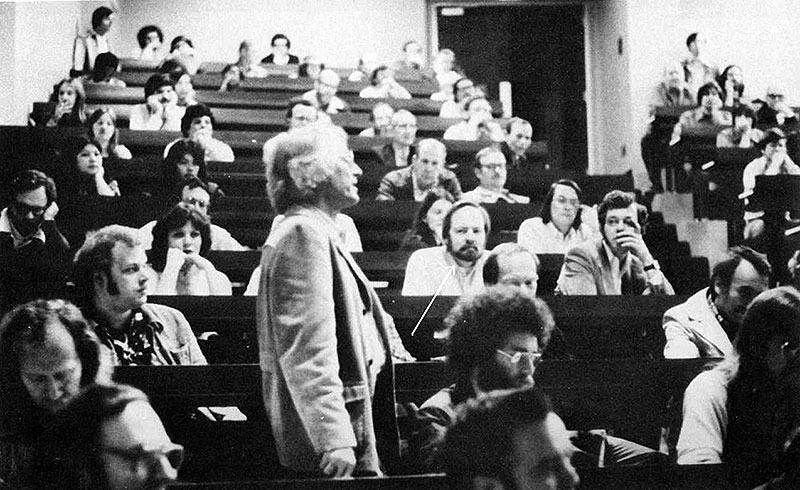

Gordon French addresses Homebrew attendees, 1979.

Photo: widely reproduced online

In 1974, I moved my workbench out of my little apartment to facilitate my contract work as Bob Marsh set about trying to devise a product to build which would include some fine center-cut pieces of walnut that he could get from a friend in Wisconsin (a digital clock was one idea). Then, without warning, we entered the future. One day in November 1974 Bob came to me in our shared garage waving a copy of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics magazine and blurting out, “Have you seen this?”

“Project Breakthrough—World’s First Minicomputer Kit” shouted the text on the cover, “Altair 8800—Save Over $1,000." The cover photo showed a nondescript box with many switches and LEDs.

Bob was excited, though. He paged to the article itself, which displayed an unhelpful block diagram (with no details) and a photo of what was said to be inside the box. “There’s nothing inside!” he crowed, "it’s going to need lots of plug-in boards to do anything useful—we can make those boards!”

And so Marsh, along with with Gary Ingram, his former co-worker from his previous career, and Steve Dompier (handling software) formed Processor Technology Corporation (slangily “Proc Tech,” which I mischievously warped into “Proctology”). I remained outside the company, doing drafting and design contracts for them but avoiding management problems assiduously.

While this was happening Fred Moore, the pacifist activist haunting the Community Computer Center in Menlo Park, was trying to establish a resource-sharing network of people from that community. The motivation was the same as for Community Memory, but he did not expect to use hands-on computer technology, and he collected index cards with contact information from people he met at CCC who expressed interest.

In February of 1975 the first Altair 8800 computer hit town, sent by its maker, Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (or MITS), to Bob Albrecht's People’s Computer Company newspaper as a review object. It was passed through the hands of various people within PCC’s community. I showed it to Efrem Lipkin who scorned it as a toy or less, but Fred Moore had an idea, which he discussed with Gordon French, a contract programmer who ran a small hobby shop near the Community Computer Center.

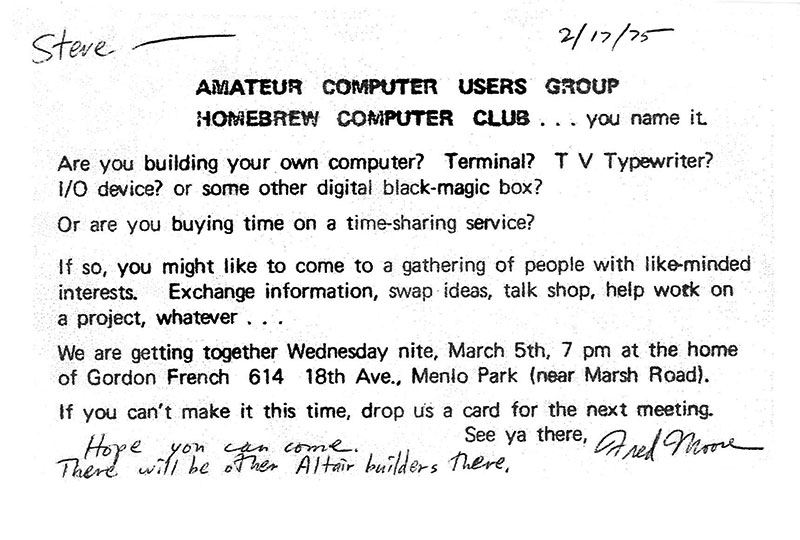

Invite to the first Homebrew Computer Club meeting.

Moore printed up a hundred or so half-page flyers announcing an “Amateur Computer User Group / Homebrew Computer Club” meeting to be held in Gordon French’s garage on March 5, 1975. Bob Marsh came into possession of one and showed it to me. Bob asked me to take him in my borrowed pickup truck, and around Silicon Valley people told other people they knew who might be interested. In Palo Alto, one Allen Baum received the flyer, and convinced his introverted friend Steve Wozniak to come with him.

On the appointed evening, during a pouring rainstorm, 30 people converged on Gordon's double-wide garage in Menlo Park, where the review copy of the Altair sat as a conversation piece, turned on but doing nothing. Steve Dompier, never passive about new developments, told the crowd of his trip to the MITS “plant” in Albuquerque to inquire about delivery on the 8800 he had ordered—we all learned of MITS’s huge backlog and limited capabilities.

Applying Community Memory’s methodology of handling secondary information, I suggested passing a signup sheet around on which each person could leave their contact information and a brief explanation of their interests. It would be copied and sent out as the first club newsletter.

Wozniak wrote that he had designed video games and his own TV Typewriter (much later I learned that he had never read about the original TVT). We decided to meet again in a month and collected some money for the newsletter's postage. At the end Marty Spergel, who ran a small business selling parts kits for Popular Electronics’ construction articles, offered any taker a free processor chip (an Intel 8008, the precursor to the MITS 8080), which was eagerly snapped up.

We had met some of our current and future customers and would meet plenty more. Processor Technology was struggling to meet orders for the company's RAM and ROM memory boards and its serial interface boards (without which there was no way to plug a Teletype terminal into the 8800) along with the kit-construction manuals. All had to be designed and documented, and I helped on all of them. Our garage began to fill up with workers, most from acquaintances within our new industry.

The Homebrew Computer Club did not have an official name until its second meeting. Someone working at the Stanford Linear Accelerator (a Federal nuclear laboratory) signed us up to use the “Orange Room,” an annex of the lunch room there. Fred Moore had called the group the “Amateur Computer Group” in his invitation, but Bob Albrecht, the editor and publisher of People’s Computer Company, had another name in mind.

An aficionado of steam beer, produced by the local Anchor Brewing Co., he suggested “Steam Beer Computer Club.” The group meeting in the Orange room reached a compromise, settling on the name “Homebrew Computer Club.” The group decided to meet every two weeks on Wednesday nights. The meetings were conducted by Gordon French, who, as a programmer of IBM computers, felt that he had a lot to teach the motley crowd.

At the third club meeting, held in the auditorium of the private Menlo School, French lectured the attendees about the right way to look at programming. When he made an incorrect statement stating that the “exclusive-OR function was asymmetric”, I vacated my seat and moved to the lobby (exclusive-OR is a completely symmetric Boolean function, no matter what IBM wants us to believe). There in the lobby an equal number of attendees were actively meeting each other—an agora was in full function. I made a mental note that we needed a way to bring this agora activity into the meeting structure on a regular basis.

This was the meeting where Steve Dompier demonstrated “Dompier Music.” He brought his Altair computer and a portable weather radio (he held a pilot’s license). After a false start when someone knocked the computer’s power plug out of its socket, Dompier loaded his program through manipulation of the front panel switches (MITS had not yet offered a way to connect a terminal to the 8800), turned on his weather radio, and pressed the computer’s “RUN” switch. Synthetic music immediately burst forth from the radio! The tune was the Beatles’ “Fool On The Hill,” rendered in scratchy low-resolution digitally generated sound. The audience was transfixed.

Then the recital ended, and Dompier urged us to “Wait—wait!” A new tune began—“Bicycle Built for Two,” otherwise known as “Daisy, Daisy,”—the tune to which the supercomputer HAL-9000 regressed as it was lobotomized in the movie “2001: a Space Odyssey”. Many in the audience recognized the tune as the world's first computer-synthesized music, programmed by Max Mathews at Bell Labs in 1961 using an IBM 7094 computer. Dompier had secured his spot as a successor to Mathews! The audience leapt to its feet in a thunderous standing ovation!

It was well-earned given how he had managed to create the event. Dompier had one of the first Altair 8800s in the Bay Area, and had been experimenting at home, writing simple programs to carry out sorting functions on a block of random numbers. The programs had to be written in the language manufactured into the Intel 8080 microprocessor, very simple instructions indeed. They had to be converted into binary codes—strings of 1’s and 0’s—by hand, on paper. Those patterns were then entered by hand through the switches and confirmed by viewing the lights on the front panel.

While testing his programs he had left his weather radio operating. As he ran his sort program a strange thing happened—the radio emitted rising tones, “Ziiip—Ziiip!—Ziiip!” as the program repeatedly ran through its sort. Dompier investigated. As his program ran through the list of numbers building the list of sorted data, the size of the unsorted list grew smaller and the sorting loop ran faster and faster. The operation of the Altair produced a lot of radio noise, and its repetition rate could be heard as tones. It was analog output unintentionally generated by the poor design of the Altair’s wiring!

Thirty hours of straight coding and testing later, Dompier emerged with a program that operated on a data “sheet music” file. The first piece of sheet music Dompier could find was “Fool on the Hill,” and he immediately converted it by hand into a list of binary numbers on paper, like the code to be input by hand using the front panel switches.

Steve later published his program with its sample music file as “Music of a Sort” in People’s Computer Company. For years thereafter Steve was serenaded by people using the program to perform their own music and play it over the phone. One group played him a multi-part piece on a conference call which they no doubt had created through skilled use of “blue box” pirate dialing devices.

Letters soon arrived at People’s Computer Company in response to Steve’s article. One was from Bill Gates, of Micro-Soft company (the name before the hyphen was dropped), who complained that the program was clearly a fraud. It did not include an output command, and how can you output anything from a computer without using the command for that purpose? It was a wonderful illustration of how someone can become stuck in the digital domain and not realize that everything material is stuck in the analog domain.

Dompier, a Navy veteran who loved learning interesting things, had come to computers as many had, through Ted Nelson’s dual flip-over book Computer Lib / Dream Machines. The latter half-title was a history and overview of computer graphics presented in nonlinear format that seemed to resonate with Dompier’s slightly manic multi-dimensional perception.

Steve later showed me a crude flight simulator he had written in BASIC, which was slow and blocky, using the VDM-1 screen as a 64 by 16 pixel display. It could calculate two screens per second, using character-size blocks as pixels, but it gave a general impression of flying. In that conversation he laid forth his overarching dream to live in a real-time simulation of Lord of the Rings and—on a nearer time scale—to navigate through data as if flying an imaginary aircraft in a flight simulation, deleting files by shooting their images. Dompier’s visions stirred in me an urge to explore what sorts of hardware might make such realizations more practical—in particular how one might empower their analog kinesthetic perception and expression to enable “flying by the seat of your pants” on the computer display.

At the fourth meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club, held at John McCarthy’s AI lab behind Stanford University, Gordon French announced that he would have to step down as leader of the meetings (and as self-appointed instructor in programming). He had accepted a six-month contract to program for the Social Security Administration in Baltimore, Maryland. We would have to choose a new meeting chair right away from the approximately 40 people present.

Marty Spergel instantly put my name forward, which may have seemed to be a pre-arranged setup but was not—I had been considering how to implement my wish to bring the activity in the lobby of the previous meeting into the main meeting. No one objected, and I modestly stepped up and took the podium.

My original idea was to divide the meeting into time segments, first calling on one person at a time for brief self-introductions and expositions of their interest that brought them to the meeting. This would allow everyone to construct a mental “map” of who was of interest to them and why. At the end of this “mapping session” the meeting would break up and people could converse freely in a series of simultaneous encounters—a “random-access” session. After that session, my concept held, we would enter another mapping/random access cycle since attendees would no doubt have new interests based upon their conversations. Perhaps three such cycles would fill the time available and many new cross- connections would be made by the end. While elegant from the standpoint of control theory (with participants’ minds stabilizing onto new trajectories through feedback) it proved impossible to reconvene after one cycle—a symptom of its success.

The fifth meeting and many thereafter were held at the auditorium of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, where I found a blackboard pointer and began to experiment in using it as a prop, primarily to indicate with precision which person in the 274-seat auditorium I would recognize for the next micro-presentation. I could also use it as a clown prop, twirling it clumsily (the only way I could) and recovering it clumsily when dropped, sometimes glowering at the audience and snapping “that didn’t happen!” I experimented with a persona of a minor boss with a Nixonian personality.

A few years later, in a different auditorium, Dr. Ed Butler brought an 8mm movie camera and shot a few minutes of film that later turned up in the documentary “The Machine that Changed the World”. I was hamming it up brandishing the pointer and pretending to be screaming at the audience—it was not a reflection of reality. I have been asked many times for the rest of that footage, but I have been unable to obtain it from the Butler family.

Unlike Gordon French, I knew I had to prevent myself from becoming part of the information flow I facilitated. In my standard introduction I warned the audience not to expect me to remember who had said what—they were to form their own mental maps. I explained that I would be concerned only with my image and not with any substantive information. I announced a rule that anyone addressing the meeting was to stand up so as to be identified by all and abide by a “selectively enforced” 90-second time limit for a mapping presentation.

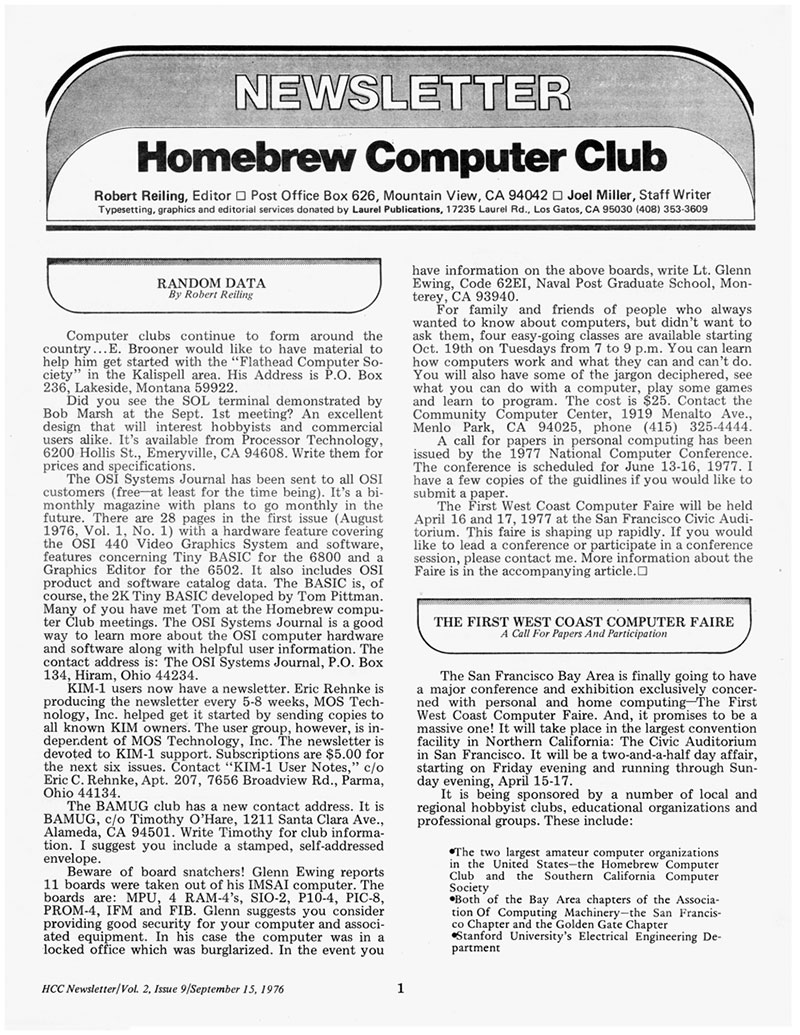

Someone appointed themselves taker of notes, which were Xeroxed up into a newsletter. A mailing list was started, printed out on Teletype roll paper and snipped into labels. Making a monetary contribution was broadly hinted as the way to increase one’s chances of receiving a newsletter in the mail. I began meetings by announcing, “The Homebrew Computer Club—(pause)—does not exist,” since we had no overall legal entity. The meeting was its only activity.

Meanwhile, some of the people active in the Homebrew Club decided to form a nonprofit corporation, and drew up the required papers. I was asked to be on the five-person board, which performed its pro-forma functions without effort. When the corporation was announced the entire meeting was energized—here was an opportunity to exert power! I threw cold water over that concept, saying that this was my meeting and I had the power to take it anywhere I wanted, so please, folks, abandon your coalition-building hopes.

At the March, 1977 meeting it was announced that the mailing list had 350 names—a sheaf of Xeroxed pages was made available (I have one). A year later the mailing list had 3,500 names. The printout roll was unfurled across the auditorium stage. Since the capacity of the room was limited to 274 it demonstrated the high “churn” of people who came, participated, and left, presumably having changed their trajectory as a result. At that 1978 meeting, I took a triptych of three photographs of the entire audience. These are the only pictures that have been published of a club meeting, and as I am behind the camera, they do not include me.

Homebrew Computer Club at the Stanford Linear Accelerator auditorium.

Photo: Stanford University

They show Robert A. Reiling, a dignified older aerospace engineer, speaking at the rostrum—he was the president of the corporation and usually made the call for donations. His meticulous record-keeping and on-time filing of forms kept the club from legally dissolving until after his death. I think of him whenever some ignorant writer describes Homebrew as consisting of nothing but hippies.

Many subcultures came through the club meetings. From tightly-buttoned amateur-radio rule-followers through the general dweebs and slobs who populated the lower technical ranks of Silicon Valley to a relatively few acid heads and psychedelic rangers, it displayed a fairly accurate cross section of Silicon Valley technological culture. The largest identifiable group (aside from ham radio licensees) was comprised of medical doctors who probably should have pursued careers in engineering.

Steve Wozniak always arrived before me and claimed the only seat with an electrical outlet (laptop computers were well in the future and the only use then for an outlet was for the cleaning crew), where he set up his development system. Together with his high-school-age acolytes Randy Wigginton and Chris Espinosa, he was designing the Apple-1 and writing Apple Integer BASIC, the interpreter language included on the ROM of the Apple computers. Many people in the club helped him with that task, as he has acknowledged.

Driving down from Berkeley where I lived, I was asked to take someone’s 13-year-old son along with me—his father would show up at the end of the meeting to retrieve him. The young fellow, Philip Robinson, later became a professor of computer science.

Homebrew Computer Club newsletter, September 1976.

In the spring of 1976 Wozniak was briefly joined by Steve Jobs. I recognized him from an encounter at Atari in 1974 when I had applied for an engineering position—Jobs was the young man in a narrow tie and neatly trimmed beard who had escorted me into (and out of) an interview with Al Alcorn, the VP of Engineering. I had equipped myself with some printouts from Community Memory, hoping to sell the concept of social media to the company, but Alcorn informed me that they were hiring only manufacturing engineers and called Jobs to escort me back out. On the way I attempted to make my pitch to Jobs but met only with slight bobbles of the head as he purposely strode forward, signifying a silent plea to “get me out of here” and away from this proselytizer. And that is how Steve Jobs missed out on social media.

Of course, that episode was before Jobs’ enlightenment-seeking voyage to India, so he was then yet to become “himself”. At the Homebrew Club meeting I was struck by the fact that he said nothing (Wozniak also never spoke up during his time there—he has cited shyness).

Once I announced the start of the Random Access meeting segment, however, Jobs came down to the well of the auditorium and dashed madly about attempting to listen to every conversation. I know he showed up twice and believe he did the same each time.

Jobs and Wozniak turned up to demonstrate their Apple-1 computer in the lobby of the auditorium a few weeks later, and I inspected it with mild interest. I saw a plain microcomputer board, admittedly including a video terminal, but limited by slow display rates.

The VDM-1 was approaching commercial release, and I knew what it could do—the Apple-1 was incapable of the same tricks. It was also situated within the 6502 software universe, which was not where most others were, and therefore had, I thought, a dubious future. I asked no questions and left them in the lobby when it as time to start the meeting. We can thus discard the screenplay fantasies that:

(a) Wozniak had to be forced to attend Homebrew for a halting presentation of Apple-1,

(b) I was boring the meeting to death lecturing with my trademark pointer when the Apple boys intruded and amazed the audience, and

(c) we were a den of shaggy hippies from a different planet (this last only appeared in a few places).

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

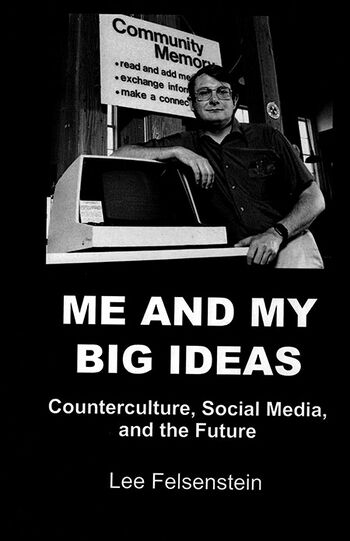

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns