Community Memory Evolves

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

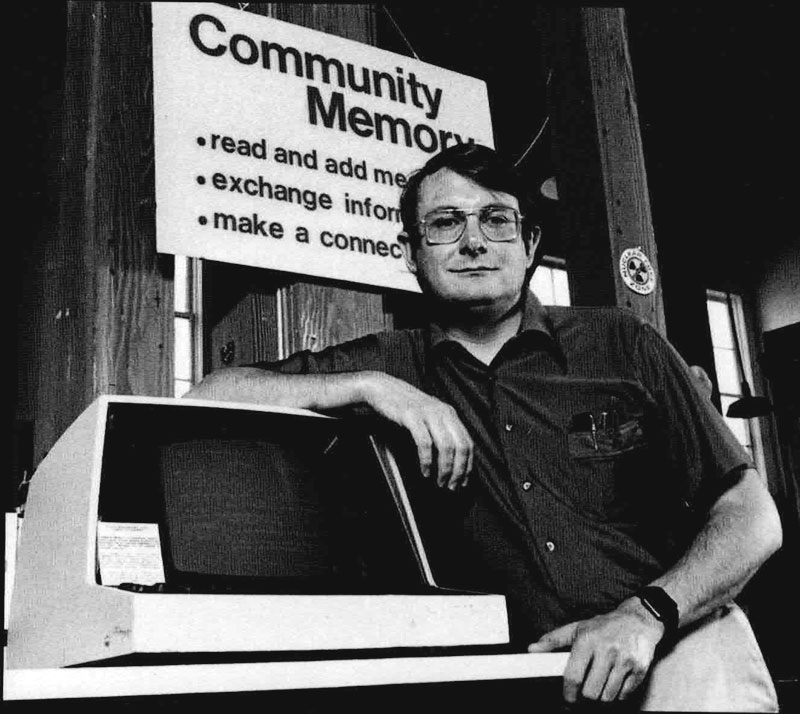

Lee Felsenstein with a later model of the Community Memory terminal.

Photo: Cindy Charles

Throughout the time I worked at Processor Technology, I retained my primary focus on Community Memory as it entered a years-long period of development work. Using my royalty income, I bought development equipment, set it up and maintained it.

Efrem Lipkin, head of Community Memory’s software effort, made some good calls. Rather than continue to trudge behind obsolescent computers that were expensive to obtain and maintain, we looked toward DEC minicomputers, especially the PDP-11 family. We would use the C language as we worked toward operating under the Unix environment, which was not possible at the outset as AT&T's license fees were prohibitive. What we could afford was DEC’s RSTS multi-user system running on a homemade PDP-11/03 that I assembled from an LSI-11 single-board computer and other a la carte components.

Community Memory developed a relational database system as its foundation and the X.25 high-speed protocols required for packet switching. In 1977 the Internet was Arpanet, restricted to military and university use, but Lipkin could see it coming as an open network.

We formed a non-profit 501 (c)(4) corporation. It could not offer tax write-offs for donations but was much more loosely constrained—it could earn tax-free income from “program related” efforts, as well as royalties from any number of sources.

The Problem of Growth

I gained insight from changes at Processor Technology. For the first year of operation (1975-1976) Proc Tech grew in the shared Berkeley garage on 4th St. until it was nearly bursting (the rule of thumb in Silicon Valley was 200 square feet minimum per employee—we had 1,100 square feet and grew to 12 employees). While it did seem like a “puppy pile” it had one advantage in its common audio space—everyone could hear everything that was happening. Several times I found myself able to shout answers to unasked questions as I overheard them develop during a phone call.

The new Proc Tech plant in Emeryville had a modern key-set phone system with lighted buttons, multiple lines, hold-and-transfer, and intercom capability, and I saw how it dampened productivity. A “professional” intercommunication system requires professional discipline in its use. That lesson has remained with me and I continue to think of ways in which the culture of a shared audio space could be developed.

Although I spent a fraction of my time at the Proc Tech plant, I did not close down my own consulting business. Efrem had paid a calligrapher to draw up the phrase “Loving Grace Cybernetics” in graceful lettering and kept it posted at his home. The phrase came from the poem by Richard Brautigan, “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”, written during his time as poet-in-residence at Cal Tech. To me, that poem evokes not the submission of humanity to presumably benevolent machines (any engineer would know what a fool’s paradise that would be), but rather a symbiosis of machine and human (which are inseparably entwined), enabling and requiring us to extend our concept of “natural culture”, which we now see as opposed to mechanistic forms, to a synthesis in which humans’ love of nature and love of creation can be fused (“... where we are freed up from our labors and joined back to our mammal brothers and sisters ...”). The phrase compels me to think in this direction—“How can technological creation be reconciled with humanistic modes of creation? How can I design to enable such reconciliation?” With Efrem's "Loving Grace Cybernetics" poster in mind, I decided to name my consulting business “LGC Engineering.”

In 1974, shortly after I took over responsibility for the rental of my Berkeley apartment from Community Memory, an antiwar activist with whom I had worked years before contacted me. He was leaving town and needed someone to take over the rental of his back yard carriage-house apartment in Berkeley (the owner was absentee). That became my home until 1991, when the property was sold. I did my design work there as my workbench moved from place to place. Berkeley soon implemented rent control, which enabled much of my creative work—otherwise I would have had to seek employment to meet “market rents.” My workbench moved first to the basement of a house in Oakland where Community Memory had its development under way, then it followed them to a house in Berkeley that was being remodeled around us.

My royalty income enabled me to set up a spacious office for my new corporation, Golemics, Inc., in 1978, but I had to give it up in 1980 after my royalties ended abruptly. Community Memory and Golemics then moved into another large, two-story space in a former woolen mill in Berkeley.

As was typical in Silicon Valley, I shifted my base of operation every few years to accommodate my income and the sizes of the projects I was working on. Most of my projects required more than my full-time attention for engineering, and recounting all the details would make it sound crazy, as it probably was. I was quoted in the book Fire in the Valley about that era as saying “A year was a lifetime in those days.”

Over the Rainbow from Osborne

The year 1980 saw me contract to provide the design of the Osborne-1 portable computer, which was delivered in January of 1981. I entered employment with the newly incorporated Osborne Computer Corporation, with 24 percent of the founders’ stock and the title of Vice President for Engineering. Unfortunately, neither I nor anyone else in the company understood the responsibilities of that position, and I acted instead as chief engineer, working with one subordinate engineer and a documentation clerk. Needless to say, I made little progress as I had to spend most of my time solving manufacturing engineering problems at the insistence of our general manager. Eventually I was moved out of the VP slot and given my own title as “R&D Fellow,” under which I set up a product development shop in another building in the same industrial park.

The whole Osborne story is another narrative, relevant here only because it was the source of funding for Community Memory. My records show that my corporation received approximately $450,000 derived from sale of some of the founders’ stock it owned to other qualified shareholders—a legally permissible transaction. The lion’s share of this money went to Pacific Software Manufacturing Company, a for-profit corporation that employed most of Community Memory’s workers. In theory, Pacific Software was supposed to amplify the money I made available, but while it came quite close to having products, it never achieved a positive cash flow. Pacific assumed the lease from Datapoint Corporation for a posh suite of offices in the high-rise Fantasy Records building a few blocks away from the Community Memory offices. I had Golemics take over the lease from Pacific as it ran out of money.

By 1983 Osborne failed to make an “IPO” (initial public offering) of its stock, also known as “going public,” and its financial house of cards crumbled. In September it entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy and my remaining stock became worthless.

Pacific Software and Community Memory were on their own. I was immediately approached by two Japanese companies from a group of five with which I had led technical negotiations at Osborne about a possible laptop design. They were both interested in my contracting with them for the design of an IBM-PC compatible laptop. I eventually signed a contract with Oki Electric Co. Ltd.

The final Vice President for Engineering of Osborne, John Hanne, had actual experience at that level, and a background in mathematics. He studied the problem of IBM compatibility and concluded correctly that “better is different is incompatible.” For the Oki development, I was able to hire some of the basic talent that Hanne had assembled as well as finding enough contract workers to carry out the development. It took 18 months and $800,000 to assemble ten prototype “Rainbow” computers. One is in the collection of the Computer History Museum (alas—the Oki floppy discs we were required to use went out of alignment and had no adjustment capability, so those prototypes are not functional).

At the project’s peak, Golemics had six employees and ten contractors at work, but after the prototypes were delivered Oki decided not to proceed with the laptop project, which would have landed us a significant contract. Thus passed the peak of my career at Golemics, with a string of smaller jobs following.

Community Memory decided to make a push to implement a second-generation system when the money stopped, and Steve Wozniak saw a demonstration of our software in 1983. He was impressed and told us in his casual way that if we “needed any grants” we should write up “a brief description” and he would come across with the money. I believe that the moment was caught by a video camera as we all gaped at each other in disbelief.

Our group was not capable of producing a proposal as small as one page. The eight-page document that resulted produced a reaction of something like panic on Steve’s part, who shouted, “I’m not going to read all that!” He became unavailable as I continued to try to contact him about the $10,000 he had promised.

Finally, conflict began to develop within Community Memory, and I called Wozniak to urge him, “they’re beginning to eat each other—we’ve got to get some money now!” He told me to come and pick up a check at his office at Apple. I raced down to Cupertino and found him out of the office but he had left a check—for $20,000. This enabled us to field the second system—Woz made a big difference at a crucial time.

With a little help from several other people we got the second version of Community Memory installed and running. All I can recall is terminals in the three Co-op markets in Berkeley (Telegraph Avenue, University Avenue, North Berkeley) and one at La Peña (a cultural center established by Chilean exiles).

The terminals were our modified Soroc IQ-120s, tied to their tables with a lock underneath, and tied to the computer through the wire-line modem extending from the serial data connector. We had a default “splash screen” with basic instructions for using the computer—enough idle time and the system would revert to it.

Community Memory was using a command-line type of interface. We wrote a relational database program, and as I understand we started out using it but moved away at some point due to the difficulty of specifying searches. The application we wrote, named Sequitur, used a spreadsheet presentation for specifying and displaying results from searches.

At Resource One the computer had a line printer with which we quickly printed off weekly digests of transactions—in Berkeley we had only character printers (daisywheel type) incapable of line-at-a-stroke operation. Accordingly, there are many fewer records of the earlier transactions in the Computer History Museum’s collection.

The Discovery of Spam

Obviously, when a bulletin-board system first opens up there is little incentive for users to enter items. At the very least someone needs to seed some questions in the hope of starting discussions. While this was developing we turned our attention to methods of encouraging clustering of index words. We created a window on the screen for suggested index words we had chosen, to encourage the use of words from within the suggested set.

Unfortunately, we noticed a tendency for some users to choose too many index words from the menu when they composed a message—in effect, the first instance of what has come to be known as spam—forcing many users to see the message almost regardless of what words they chose for their search. Like spam messages of the future, they turned out to be mostly adolescent boasting and invective. Adolescent males discovered the terminals and used them as a stage to flaunt their newfound abilities to write. We later discovered that the son of the primary theater critic of the San Francisco press claimed to have learned to write at our terminals (he now holds his father’s old position).

I think it would be fair to say that a number of other boys learned to write this way, and likely some girls, too (we had no way of knowing the gender of our users). During adolescence the young expand their boundaries, discovering what new efforts yield positive or negative results. The ones who survive will have the experience to build upon for the rest of their lives.

The impulse to play is strong and universal among humans (and even in some animals)—I was relying on it when I conceptualized the Tom Swift Terminal. We would be fools if we never accommodated it in our societal institutions, though as Illich and Paul Goodman have pointed out, our educational structure tends to beat it out of our youth.

In 1984 Steve Levy’s book Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution was published. He had sought me out for an interview while he was still groping for a unifying concept. I recall one long session in a laundromat near Osborne in 1982 while my clothes washed. Levy, who graduated from my high school (Central High School in Philadelphia) about ten years after me, had apparently started out working on a book or a series of articles on computer games for Rolling Stone magazine. At our third interview he announced that he now had a thesis—the “Hacker Ethic,” which provides the basis of the book. It can be summarized, I believe, as the rules for playing the game of hacking—applying one's creative faculties in a playful fashion, in a group, to learning how to circumvent rules and prohibitions placed around access to the important technologies of modern society.

Hacking is for the most part non-remunerative—the benefit lies in self-improvement and in gaining respect from one’s cohort. And that self-improvement is distributed over a small community, since a sufficiently complex target system requires that most problems be attacked by a group. In one of the concluding interviews, I spoke of how hacking was the response to society’s stricture—“This you shall not know,”—hacking was part of the continuing struggle against suppression of knowledge, and could be defined as turning one’s own creative capabilities toward that struggle. Unfortunately, Levy’s transcriber of our taped interview apparently got confused and typed, “This you shall not do,” reducing the significance of hacking to simple disobedience of reasonable rules.

I have disputed this with Levy and he claims that the transcription reflected my actual words, but I know what I said and will some day be able to prove it (the tapes survive, though Levy says that it would be difficult finding the right one, and he appears not highly motivated to do so).

Much of his original material on computer games makes up the final two-thirds of the book, and I tell readers that they can safely skip or skim over it. Better, I tell them, to invest the time in reading the section titled, “Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums” in Stewart Brand’s 1974 book II Cybernetic Frontiers, expanded from a Rolling Stone article published in December 1972. There Brand explores the world of hackers working in the advanced development labs on the San Francisco Peninsula, at Stanford University, Stanford Research Institute and Xerox PARC. He describes the wonders under development at PARC—the article revealed the name of the company, which resulted in an explosion at corporate headquarters—in the book Xerox is renamed “Shy Computer Company.” Brand is enthralled by the playfulness of the programmers, their references to Tolkien in naming their rooms, for example, and their whole-body involvement in Spacewar!, a game of realistic warfare in space using accurate physical simulation of orbital behavior.

At the end of the book he reports on a visit to Resource One, then still writing its software and checking out the computer. I appear in the corner of a group photo (by the now-famed Annie Liebowitz, who worked for Rolling Stone at the time) and I was the source of half of Brand’s information, since he interviewed only me and Pam Hardt. His conclusion was that while we were sincere in our societal goals we were “short on true hacker time-wasting frivolity; they’re warm, but rather stodgier than some of the Government-funded folks.”

I will take some credit for that evaluation, crawling as I was out of my depressive mental pit. Several of Resource One’s programmers were conscientious objectors to the Vietnam war, required to work in the nonprofit sector under threat of imprisonment. None of us felt comfortable living in a fantasy world.

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns