Community Memory: The Beginning

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

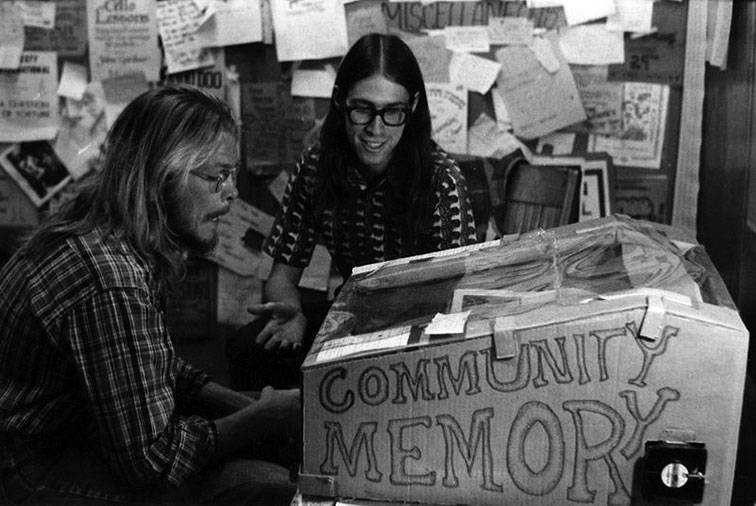

First iteration of the Community Memory Project at Leopold's Records in Berkeley, 1974.

Some of our people met with the council of county librarians who maintained an inter-library index system. They told us that we appeared to be a library with nothing on the shelves—their advice was to put something on the shelves and see who wanted it. Efrem Lipkin had been a participant in the meeting (I was not), and he returned with the suggestion that we simply put a terminal in a public place and see what accumulated, whereupon we would have a better idea of who would find it useful.

I was dubious, as I thought we would require sponsorship from community organizations to function in the community-building context that motivated my participation. But I wasn’t about to veto the idea, and I joined Lipkin in advocating it.

Leopold’s

The student government at Berkeley (the Associated Students of the University of California) had responded to student dissatisfaction with the high cost of phonograph records by founding a record store of its own dedicated to bringing prices down. We made a presentation to their board (the student council) about placing a terminal at the store as an electronic bulletin board. They were perfectly agreeable and approved the request immediately without opposition.

The store, the "Leopold Stokowski Memorial Service Pavilion" (later shortened to "Leopold’s Records" after hearing from Stokowski’s lawyers), was located on the second floor of a retail building at 2518 Durant Way, one block from campus.

Access from the street at the time was up a stairway and down a long hall having walls papered with notices and posters. Near the end of the hallway was a bulletin board used primarily by musicians—we chose that spot for our terminal.

We knew that a small number of telephone prefixes in Oakland would provide free local service to San Francisco, so we ordered a line installed on one of them, enabling the terminal to remain “on line” all day for the cost of a local call.

The terminal was one of our donated Teletype 33s, a device too noisy for use in public spaces. We had already dealt with the silencing issue at our office, and I hand-built a cardboard enclosure insulated inside with urethane foam and a Velcro-secured clear flexible vinyl flap as a window. Two holes on the front of the box with star-cutout vinyl gaskets allowed a user to reach through to the keyboard. A small vent fan prevented overheating and we hand-lettered “Community Memory” on the side in psychedelic script. This sat on a card table with a chair in front and another to the side where our minder sat.

“It’s Alive!”

We opened on August 8, 1973, without prior notice. As people approached down the hallway our minder greeted them with the words “Would you like to use our electronic bulletin board? We’re using a computer.” The chair in front was empty. I expected many people to approach it with trepidation or hostility, but was pleasantly surprised to see this happen only once. The typical response was “Oh—can I use it?”

We made the instructions as simple as possible—“Think of a word, type it and push the green button” (the carriage return key was covered with green tape). If the user pressed the green return key without typing anything, the null input caused a short explanatory sentence to be printed. Since the great majority of students had never interacted with any sort of computer terminal, it was novel for them to see the terminal self-animate and explain how it could be used.

There was no list of index words—in later generations we would experiment with suggestions through different methods. While Lipkin had expected only three categories to be used (jobs, cars, and housing), we found that people entered quite a broad range of index words.

We had stumbled into an unsuspected “sweet spot.” Trusting the user to imagine the right index word worked, as long as retries were easy and free. Each word or group of words displayed the first lines of retrieved messages—at slow Teletype speeds we had to conserve the users’ attention span. The full message could be printed by entering the number of the displayed line.

The message contents displayed creativity and a broad range of interests. At least one image in typewriter graphics (a sailboat image formed by text characters) appeared—someone had to have entered it from a pre-existing data file through the paper tape reading capability of the Model 33—entry direct from the keyboard would have been impractical. A street poet (known as j. Poet) became a regular, entering doggerel with the footer line “for more poetry call me at (phone number)”. I planted an article in the Berkeley Barb, which by that time had been recovered by its original owner, announcing the system's opening. There was no shortage of users. Years later I summarized the effort by commenting, “We opened the door to cyberspace and found that it was hospitable territory.”

Someone in our circle of supporters was on the staff of the Mission branch of the San Francisco Public Library. The second terminal was set up there a few months later. Community Memory was a reality—whatever it was going to be.

Leopold’s was a busy store, and apparently word spread of our strange new machine. Traffic from the musicians’ bulletin board began to show up on Community Memory. Jude Milhon and Mark Szpakowski began seeding questions on it, trying to get users to offer answers, mostly about where to obtain unusual or scarce objects or foods.

Bagels were one of those foods. I grew up eating those toroidal rolls, dense and distinct in flavor, cooked floating on boiling water and with an egg glaze finish, but that was in one of the largest Jewish communities in the world. Bagels were a specialty food in San Francisco, a novelty. Jude and friends entered an item asking “Where can I find good bagels in the Bay Area?” with index word “bagels.” Three responses showed up almost immediately. Two were as expected, giving the names and locations of stores that carried bagels. The third was the winner—“If you call xxx-yyyy and ask for (name), an ex-bagel maker will teach you how to make bagels”, it read in its entirety.

In 1970 Ivan Illich published a book titled Deschooling Society. Its thesis is that the institution of public education should be replaced by the sorts of informal learning that is prevalent in rural village cultures. It is a radical book, somewhat too much so for my blood, but it ends with a coda that appears to result from talks with the artificial intelligence gurus at MIT. In it, Illich suggests that computers might be useful to connect people having something to teach to others who wish to learn it, as “learning exchanges,” one way of implementing his vision of human “learning webs.”

This “bagels dialogue” that appeared on Community Memory was confirmation that learning exchanges were not only possible but were latent within the community of users and required only the technological substructure to manifest. This did not mean that a whole structure of learning exchanges would spontaneously appear—that requires organization, funding and effort—but this incident, I believe, demonstrated the possibility. Community Memory users created personae. A Dr. Benway (out of William S. Burroughs’ novel Naked Lunch) cropped up and others (one Dr. Sunway, for example) played along with him (or her?). Once users realized that there was no way of establishing verified identities, the limits to discourse became much broader, though generally constrained within limits of objectionability. We had created an ideal medium for short textual graffiti, apparently.

Starting almost immediately after the initial opening we began to collect and select database items for weekly publication as sheaves of printouts, the “CM Digest.” Some of these are part of the collection at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. As I have determined personally, reading through them can be exhausting, in large part because they are pdf image files and not organized for indexed retrieval—but they can be read through a web browser.

Poring through even a small sample of the 1974 database drives home the point that there was significant use of the terminals at Leopold’s and the Mission library branch (a keyword prefixed by a delta symbol identifies the terminal used—entries from the terminals at the Resource One office did not add the delta symbol). There was much discussion of learning exchanges and apparently a private conference on the topic was organized in 1974 among various interested parties using Community Memory.

Protecting the Hardware

I was facing a philosophical problem of whether to take the advice of others and armor the [Community Memory] terminal to protect it from the public or to use a different approach. [Ivan Illich’s concept of] conviviality provided that alternative. The protection, support, repair, and improvement of the future Community Memory terminal could be provided by its users and their communities, if it were designed with that in mind and supported by other information.

Efrem Lipkin had introduced me to the technical manuals describing the operation of Digital Equipment Corporation’s PDP-11 minicomputers, which were much better designed from the standpoint of conviviality than the Nova minicomputer I had dealt with at Ampex. Many engineers and hackers have learned digital design from those excellent DEC manuals, just as I learned about bus-oriented design from them—they provided a great example of conviviality at work.

Rather than a haystack of data channels going from and to individual destinations, the PDP-11 architecture was organized around common data and address busses. In electrical terminology a “bus” is a wire connected to multiple places—our familiar utility power lines (or mains) are busses by this definition. In computers, busses are groups of wires that conduct digital patterns to multiple destinations, with the definition of the patterns defining their intended functions. Interconnecting computers’ modules through a common bus provides a simple, low-cost method of assembling a computer. Due to the propagation times of signals the bus cannot be much longer than 18 inches (45 cm), so they came into use only with the advent of minicomputers.

A “bus-oriented architecture” was therefore the physical key to a convivial design that could start life as an “unintelligent terminal” and grow, given that additional modules would function properly wherever they were installed along the busses. Upgrade would be simple.

This was the genesis of what I came to call the “Tom Swift Terminal”—a terminal that could grow into an intelligent terminal, and from there to a full computer and possibly an array of interconnected computers. It could be configured by people involved in its use who were sufficiently interested in tinkering with the equipment. I named it after Tom Swift, a teen-age Thomas Edison character in a boys’ book series created in the 1910s, wherein Tom and his friends invented their way through improbable adventures.

I began writing an engineering specification for such a device. It had to work as a terminal without a “central processor,” implying an architecture in which the central element was memory (a basic element of the design philosophy). Data transfer would be through "direct memory access" (DMA), performed by hardware working in place of the missing central processor—hardware that could be replaced by a central processor module when it finally arrived at an acceptable price.

I summarized my design philosophy in the sentence; “In order to survive in a public-access environment, a piece of computer equipment must grow a computer club around itself.” I included a page explaining the concept of “Convivial Design” as I understood it.

Leaving Leopold's

The first version of the Community Memory system lasted from August 1973 to January 1975. In Early 1974 we closed the Leopold’s Records terminal and opened one a few blocks away in a new “Whole Earth Access Store,” which had appeared on Shattuck Avenue without the blessing of the publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog (which bestowed its blessing retroactively). The few blocks’ distance was significant, as Shattuck Avenue was firmly in the downtown business district of Berkeley whereas Leopold’s was in the Telegraph Avenue student area, a focal point for hippies, artists, runaway youth and people living by their wits. When we moved the terminal we saw the musicians’ traffic decline dramatically. Location was apparently all-important and the musicians were not inclined to follow the terminal to a different part of town.

In the fall of 1974 the Community Memory Project separated from Resource One. The system was shut down in an orderly fashion and the group began the long process of creating the necessary software and hardware for future versions.

The Resource One computer was used thereafter to publish a printed San Francisco Social Services Referral Directory, a task more in line with their original proposal for the use of the machine. As its name implies, it was distributed to agencies around San Francisco and updated monthly to provide a common data base of available services and resources.

Community Memory was a different animal from a commercial system. It was a civil system whose success would be a function of the degree to which functioning communities could be built and sustained through its use. We had no plan for measuring the system’s effectiveness. We never chased down the ex-bagel-maker, for example, to see if anyone had taken him up on his offer to teach his art. Our goals did not lend themselves to quantization or measurement—what units would one use to measure the quality of a community? Computers are, of course, excellent at recording events such as accesses of items, with time, date, and terminal location, but that’s only within the system. The important dynamic lies in the follow-up contacts outside the system.

We did do some measurement of index words and their frequencies of appearance. On the first version the vast majority of words were used only once. We considered this to be a problem, an indication of individual isolation. We tried different experiments in the second version, attempting to compile and present suggested index words in the opening screen (we stopped using Teletypes after the first version, replacing them with video display terminals).

Finally, in the third system, we abandoned the relational databases as too clumsy when queries had to be generated and went to an architecture using two types of retrieval systems. A user could both enter index words freely and/or link to another item. Maps of such linkages would be complex and it's not clear what they would have shown. What we specifically did not do was to force users into groups or classes for directing their attention in ways that would profit us.

We did attach coinboxes to our terminals in the third system, with the intention of placing a low cost on entering an item (as opposed to simply reading it), but we never implemented them. Community Memory was not designed to be economically self-contained. If it created value for the community then we believed the community would support it.

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns