Resource One

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

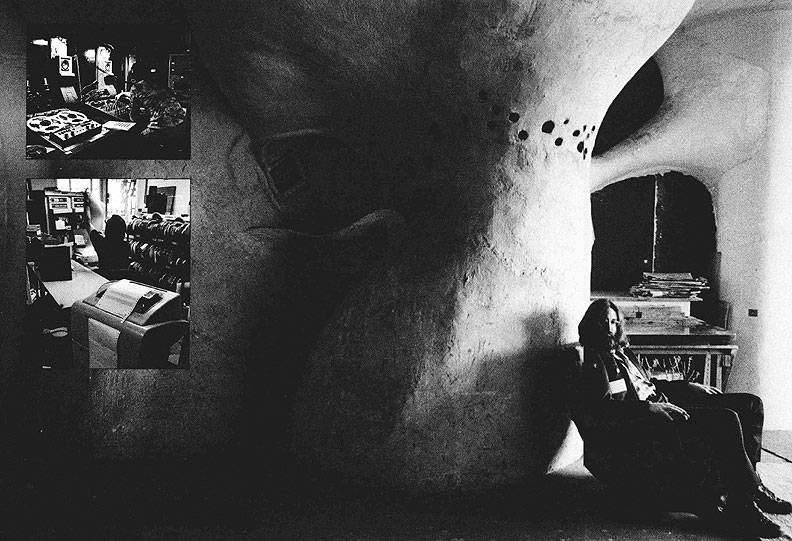

Project One recording studio, the original SDS-940 computer, and a sculptured wall.

Photo by R. Valentine Atkinson

One evening in 1971 I was walking on Telegraph Avenue in Berkley when I was accosted by Arnie, someone I knew from my work with various political groups. I knew him as somewhat "off" in his halting speech and the intensity with which he pursued ideas and details.

“Lee!” he shouted at me as he ran up, “That stuff you’ve been talking about! There’s a group in San Francisco that’s getting a computer to do that!” I got the phone number from him. But for that encounter I might not have heard about Resource One until years later.

On a later evening that fall I showed up at a four-story industrial building at 1380 Howard Street in San Francisco, at the corner of Tenth and Howard streets in the South of Market district. There was probably no other place like it in the world at the time. Built in 1928 as a candy factory made of poured reinforced concrete, it looked no different from the outside than many other industrial buildings in the area. Prior to the 1906 earthquake and fire the area had been a ramshackle residential/industrial district.

1380 Howard Street was a model of the new, totally fireproof and earthquake-proof buildings erected to stringent new post-quake codes, each floor a grid of cylindrical pillars flaring out conically to the ceiling, all floors reinforced with grids of steel rods, built to last for centuries. By 1970, however, the candy company had moved out and the owner was having little luck in attracting an industrial tenant.

Then the trauma of Kent State University happened on May 4, 1970. The invasion of Cambodia (“incursion” in sanitized official language—a word without a verb form) had precipitated nationwide protest and shutdowns of colleges and universities, setting the stage for the Ohio National Guard to play kill-the- hippies with live ammunition.

The trauma was nationwide among college-age people. At Berkeley the school of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science was the first to declare a strike, I later learned. A lot of students paused their studies to meet and debate possible strategies and tactics and to organize protest activities. In microcosm, three Computer Science students left school and set out to bring computer power, however they could, to the counterculture.

Pam Hardt, Niels Neustrup, and Chris Macie struck out on a path that led them to 1380 Howard, where the San Francisco Switchboard had set up after breaking away from the Haight Ashbury Switchboard, leaving it in that neighborhood where it functioned since 1967. Neustrup, pursued by the draft, could not continue with the others. The building had been inhabited over a short period during the Cambodia crisis based on an announcement on an FM radio station with a counterculture listenership. “Help build a community in a warehouse” was the basic message, and many people showed up.

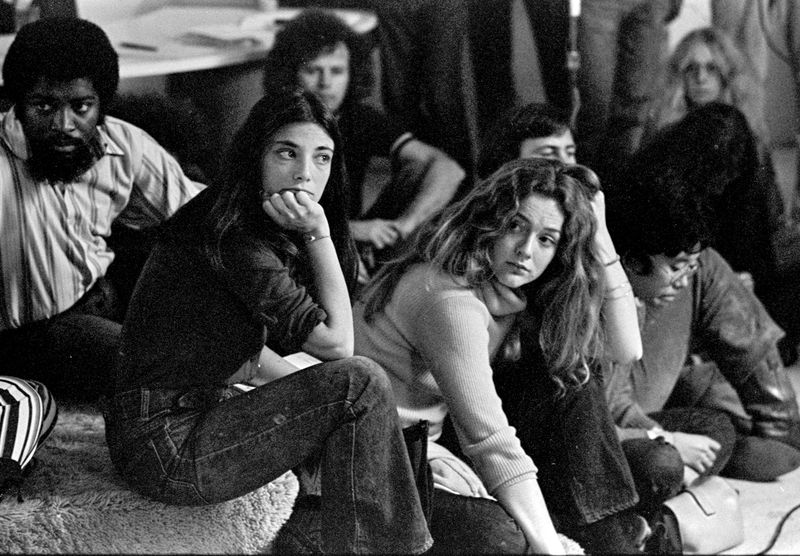

Meeting in early days of Project One.

Photo: Lynn Adler

The organizers were a few architects and one structural engineer. Later I would joke that a group like that, motivated by traumatic events, would inevitably seek a solution in renovating a building. Meeting in the cold caverns of an unheated, unlit concrete building, they set to work constructing their environment in which to live and work as a community. Everyone involved learned construction skills needed to install sheetrock walls. Gunpowder-driven hammers blasted threaded bolts into the concrete, to which the metal runners and studs for walls were attached.

The landlord was amenable to all this. The new inhabitants agreed to pay rent and anything permanently attached to the building legally became the landlord's property. He participated in many of the parties held during the inhabitation process.

Lawyers among the inhabitants discovered a type of legal entity, originally invented for the Elks Club, called an “unincorporated nonprofit association” that could enter into contracts—they set one up and named it “One.” The building became known as “Project One.”

Techno-commune

This was all in progress in January 1971 when two Standard Oil tankers collided under the Golden Gate bridge, unleashing a massive oil spill. Ecological damage was extensive, and a hue and cry arose within the counterculture as well as the middle-class “conservation culture” in the Bay Area. The underground FM radio stations were full of appeals for help of all sorts in the cleanup.

Project One threw itself overnight into setting up a “war room” for coordinating volunteer efforts. Telephone switchboard equipment routinely left behind in vacant buildings was scrounged and re-installed by people with the requisite skills. The war room served as an effective nerve center for volunteer cleanup and wildlife rescue efforts, raising Project One’s profile within the community. “Technological commune” was one term that was bandied about, though it never had a common economic structure.

The San Francisco Switchboard, which had retained its nonprofit corporate structure when it split from the Haight Ashbury Switchboard, was a founding original member of Project One and served a significant function in handling the telephone traffic and giving referrals. Pam Hardt worked with the Switchboard when she first showed up, and when the founder departed she inherited the corporation and changed its name to Resource One.

Like myself, Pam had been converging on setting up a computerized switchboard system focused not so much on finding people as on finding resources. Hardt, Macie and others began to seek donations of time on time-sharing computers. Through Project One they met Pacific Change, a group of children of the San Francisco business establishment seeking ways to understand and assist the counterculture.

This led to a unique instance of fundraising. The San Francisco establishment parents of the Pacific Change folk had been taken aback by the emergence of the counterculture, and together they formed a group called “Youth Meets the Establishment.”

It was there that Pam performed heroic work selling the idea of computer technology organized at Resource One as a tool for unification of switchboard files and other methods of bringing coherence to the alien culture that had sprung up to entice the young. I heard of how Pam, during a retreat, managed to back the Chairman of the Board of the mighty Bank of America into a corner, haranguing him about the paltry donation to which his foundation had committed. “You have to do better!”, she insisted—and he did.

The Nexus of Personal Computing

Books are only now being written describing the network of individuals, organizations and interactions that led to the development of personal computers. I will describe it only as I experienced it, not from any global viewpoint. The center of the Silicon Valley counterculture ("bohemian culture” before Theodore Roszak invented the later phrase) was Kepler’s Bookstore. Roy Kepler had been a pacifist conscientious objector during World War II and opened a new/used book store in Menlo Park in 1955, which became a center for pacifist and other nonconformist thinkers and activists. Kepler’s Books became a place to browse not only for books, but for kindred people (as per my experience when I spent my first summer away from Berkeley in 1967 working in Silicon Valley).

It qualified as a “third place” for Stanford students and faculty, one of a few stores where obscure literary quarterlies could be found and where there was seating and coffee to facilitate discussion. When speakers on political topics gave talks there Roy Kepler would participate from the front—always ready to criticize them for not taking a sufficiently pacifist position.

In 1967 Roy Kepler helped establish the “Midpeninsula Free University” in a nearby storefront. It served as the organizing point for a network of pop-up classes offered by members of the community, enriching the interconnections among people who considered themselves independent thinkers. The next year saw the opening of the Palo Alto Research Center by Xerox, which joined the Stanford Research Institute and Prof. John McCarthy’s Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL) as attractants to creative and free-thinking researchers, engineers and scientists. It is noteworthy that this community had a technologically-oriented base as compared with the literary base of the San Francisco beats.

That year, 1968, Stewart Brand, who had engaged with the “Beat” writers and artists after leaving Stanford, set up the offices of the Whole Earth Catalog a block away from Kepler’s and the Free U. The Catalog was a counterculture magazine with the slogan "access to tools," featuring articles and product reviews that helped people become self-sufficient in various ways. The second edition of the Catalog has a page picturing a brush-cut Bob Albrecht teaching the use of an electronic desk calculator to elementary school students under the aegis of the Portola Institute, a nonprofit set up by consultant Dick Raymond.

The Portola Institute served as the origin point for the Whole Earth Catalog and later for Albrecht’s People’s Computer Company, a tabloid newspaper for readers interested in teaching computer programming to children. All of this was operating within a one-block radius of Kepler’s Books.

Out of this milieu came the Community Computer Center, set up in a tiny strip mall two miles away as a sort of laboratory for Albrecht’s ideas for introducing kids to computers. Initially it had Teletype 33 terminals with modems, and rented computer time on timesharing commercial computer systems. Albrecht made his games available on the timesharing system—users paid 50 cents an hour and its clientele were primarily children of the researchers and engineers who frequented Kepler’s.

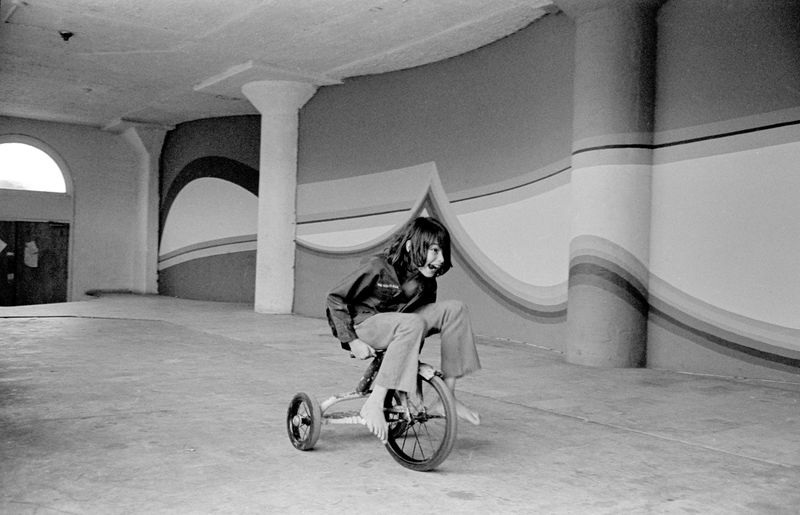

Kids had the run of the place in the early days at Project One.

Photo: Lynn Adler

The contact list at Resource One included people at all of these places—Pam had done a remarkable networking job. There were many names on that list that would become part of computer history, including a future CEO of mine.

When I showed up at Resource One one evening I was still working at Ampex during the day. I was directed to a room in the basement where I met Pam and some others, including Al Montoya, said to have been a maintenance technician for the SDS-940 mainframe computer that had been committed to Resource One “on long-term loan."

I began to contend with learning about a completely unknown computer, fitting in with a new set of people, and discovering what I could do that could be of help going forward. As I write this, I realize how poor I was (at age 26) with social skills and with navigating in unknown technical territory.

The only professor not to have bestowed an “F” grade upon me in my previous quarter was Prof. Otto J. M. Smith. I had to meet with him to discuss my “Incomplete” status in his EE128 course and how the grade could be settled. Smith met with relevant deans several times in the process and was assigned as my adviser (I imagine the deans concluding, “you’re so interested in him—you take him!”). I would re-take his course as well as the other courses I had flunked. What I learned from Smith about “s-plane” and “root-locus stability analysis” served me very well later and counts as one of my lucky strikes.

In my interactions at Resource One, however, I still tended to think of other people as threats rather than as potential helpers, and to look at the unknown as something to be avoided rather than explored. Through the group I was nonetheless able to begin my exploration of the nascent personal computer underground in and around Menlo Park, California. I had a foothold in a new world.

previous article • continue reading

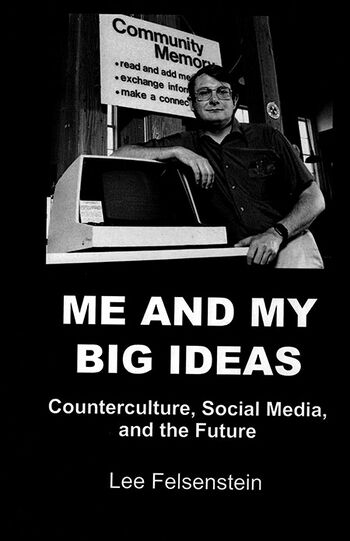

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns