Installing a Mainframe at Project One

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

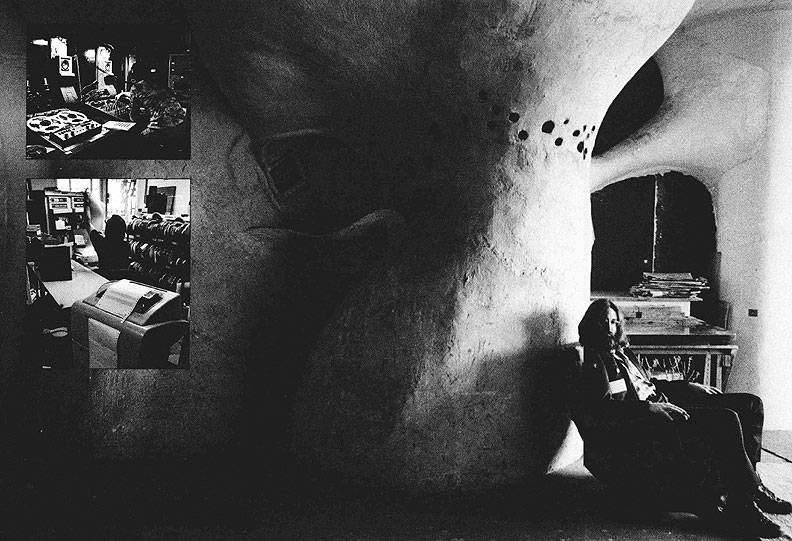

Project One recording studio, the original SDS-940 computer, and a sculptured wall.

Photo by R. Valentine Atkinson

As the sands of 1971 ran through the hourglass, I struggled to understand the documentation that Resource One received in advance of delivery of the SDS-940. Much of the description was in terms of logic equations and signal block diagrams with which I was not yet familiar. I was told not to worry, that Montoya would train me in the technology and its maintenance.

I had already rented a basement room at Project One, the four-story “warehouse community” where Resource One was installing the SDS-940 mainframe. I threw myself into the work of installing the computer. It required 23 tons of air conditioning, and a sealed room built within the two-story-high space.

When the equipment racks were installed, Montoya, my tutor-to-be in maintenance, disappeared. When months later he reappeared and I demanded to know where he had gone, he off-handedly replied, “I’m here now.” Of course, he soon disappeared permanently. I now understand this to be the behavior of an addict.

The SDS-940 was designed for timesharing use, originating in a project named Genie at UC Berkeley. That project created memory-management hardware to add to an earlier SDS-9300 and Butler Lampson, the project leader, forced Scientific Data Systems to put the resulting 940 on the market against the CEO's wishes. A total of 57 were built, of which half were in service at Tymshare Corporation in Silicon Valley—the computer's name changed to XDS-940 when Xerox bought the company in 1968.

The computer at Resource One had been leased by Stanford Research Institute, where the legendary Doug Engelbart used it to stage his history-making demonstration of personal use of computers in 1968. After the expiration of Stanford's lease it was returned to Transamerica Leasing Company. Transamerica had very close financial ties to Bank of America, who directed Transamerica to give it to Resource One on “long term loan,” with terms basically specified as “please don’t give it back.”

The Crew Assembles

We also got $120,000 in cash. We were very stingy about pay, and many of the programmers were conscientious objectors required to work for a nonprofit though supported informally by their families. I was not so fortunate and had to take on contract work to stay afloat.

Our contact network gave us access to many people who had worked on or with the SDS-940. I brought in a friend, Efrem Lipkin, who was a systems programmer, a skill we needed. He brought in some friends of his—Ken Colstad and Mark Szpakowski from Buckminster Fuller's World Game event in San Francisco, as well as Judeth Milhon, Efrem’s long-term partner, later to be known as Saint Jude when she edited the neo-cyber-psychedelic Mondo 2000 magazine.

With the help of L. Peter Deutsch and Paul Heckel we obtained and installed a copy of the defunct Berkeley Computer Corporation’s operating system, written on an SDS-940 in a language named QSPL (Quick Systems Programming Language), which could be found on almost no other computers. We had a lot of help, very little of which I solicited. I took charge of the telephone interface and constructed a modem rack.

We spent some of the cash we had raised on a double-wide 120 MB disc-pack drive (considered pretty big at the time). Fred Wright designed an adapter for a commercially available disc controller (emulating the same Nova minicomputer I had programmed in 1970).

People from Project One were paid to perform the wire-wrap construction of the adapter under Fred's direction while I designed the necessary sheet metal frame and had it fabricated by a craftsman in the building. Fred and I went deep into the guts of the 940, discovering and fixing an incorrect voltage connection that must have made the 940 unreliable—it had been part of the original construction.

I spent every available moment working, telling myself that this was my calling. I prepared my own breakfast in my quarters on a hotplate, my lunch was a sandwich from a nearby shop and dinner was a hamburger steak dinner from a coffeeshop on nearby Market Street that closed at midnight.

Walking out of the building, I would experience feelings of shame at being away. I later learned that this was a symptom of psychological “institutionalization,” the condition that causes released prisoners to re-offend so that they can return to the order and familiarity of prison.

I made progress in my therapy, at one point discarding my signature rumpled work clothes in favor of a colorful turtleneck and sweater-vest outfit. Eventually, in 1974 Efrem and his household pried me out by pressing to have Resource One rent a Berkeley apartment as a local office where I would live and they could work. I am grateful for that move and spent a couple of weeks there recovering from institutionalization through domesticity.

Gradually the 940 came alive. We got some used Teletype 33s donated along with some old modems, most built in wooden boxes which hinged open to allow a telephone handset to be cradled inside. We also received a donation of a “portable terminal,” a Teletype mechanism repackaged in one of two lumpy plastic housings, the other containing the modem and power supply. I repaired the mechanism and loaned it to Michael Rossman, who used it for conferencing on the EIES system in New Jersey, one of the earliest bulletin-board systems, though not open to public use.

Visit of a Hacker Eminence

One day we were visited by Richard Greenblatt, a famous MIT hacker, who stayed in the building for a few days. I recall him holding forth before a small group of programmers, arms spread wide, proclaiming, “Let’s write an information retrieval program in 24 hours!” There followed much discussion in jargon of which I recall only the term “cluster-buster routines.” A key factor for information retrieval is the use of indexing words, or keywords—a user enters an index word and receives all of the information indexed by that word. The existing systems we knew of allowed only a predetermined list of indexing words—a user adding new information could use only those words that were already defined in the system.

The work initiated by Richard Greenblatt became the foundation of ROGIRS—"Resource One Generalized Information Retrieval System". Any user of ROGIRS could declare an indexing word—it was not constrained to a predetermined list. All of our effort was directed at getting the 940 into dial-up operation, with ROGIRS operational, but very little work had been done on marketing—finding a way to get it used. Our only concept was either to use it as an in-house “resource center” for Project One or to get switchboards in the San Francisco area to use it as a common file—Resource One’s original concept.

The Devil in the Details

While the unified database for switchboards was a good idea in general, the mechanics of making that happen turned out to be elusive. Leasing a Teletype cost $150 per month, far beyond the budget of a threadbare switchboard at the time. While we had started as a renaming of the San Francisco Switchboard we had not kept in touch with the others, and by the time ROGIRS was ready we were but a vestigial rumor within the switchboard community, as we discovered when we tried to re- establish contact.

Not only did the cost in cash prove an obstacle, but the conceptual effort needed to move from a simple card-file box to a system on a computer was prohibitive. Typically, the filing system of a switchboard resided in the head of its director, who would “burn out” and leave, with the files reconstituted by the next director. The last thing any switchboard was ready for was the work of transitioning its files to a real-time computer information retrieval system.

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns