The Palace of the Legion of Honor

Historical Essay

Part One by James Brook

Part Two by Bernie Lubell, Dean MacCannell, and Juliet Flower MacCannell

The Palace of the Legion of Honor in the mid-1990s.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Palace of the Legion of Honor in the time of Covid-19, June 2020.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Over Whose Dead Bodies?

Grave Ironies at the Legion of Honor

No architect or patron could ask for a more dramatic site for a museum of art: designed by George Applegarth for Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor sits atop a bluff at Lands End overlooking San Francisco Bay. The Court of Honor, the formal peristyle of the U-shaped, neoclassical memorial to Californians who fell in the First World War, opens via a Roman triumphal arch toward the Golden Gate. Ionic columns march past a copy of Auguste Rodin's Thinker to the museum entrance, framed by Corinthian columns, at the bottom of the U. Over the entrance porch a motto in French admonishes museum-goers: “Honneur et Patrie.” Just over the door is the middle panel of a triptych in relief depicting a suovetaurelia, the Roman ritual sacrifice of a pig, a ram, and bull to Mars, god of war. Panels 1 and 3 of the triptych cap the ends of the U. Equestrian statues of Christian soldiers Joan of Arc and El Cid stand at the ready in the broad sweep of lawn before the Legion, defending the approach to the Roman arch from the parking lot below. The façade at the other end of the building at the bottom of the U turns outward to the Pacific Ocean.

Even a casual glance reveals the almost hysterical dedication to empire this building embodies. If the Palace of the Legion of Honor were a dream, you would want to wake up and write it down for historical analysis. . . . How did imperial images of the Greeks, Romans, Spanish, and French become implanted on this spot in San Francisco, and what does this art museum have to do with the California dead of the First World War? Are there deeper meanings to be read from this wish-fulfillment in poured concrete?

Digging a little into the dream life of Alma Spreckels turns up some answers. Born in 1881 to poor Danish immigrants trying to farm the sand dunes at the edge of San Francisco, Alma de Bretteville was a descendant of a French nobleman who had fled to Denmark during the Revolution. She left school early to help her mother with the family laundry business before working first as a stenographer and then as an artists model. Nude portraits of this teenager with “a buxom, Rubenesque figure” gained pride of place in San Francisco watering holes of the time.

Alma Spreckels, 1903, apx. 20 years of age.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

In 1902, at the age of nineteen, she took up with an Alaskan gold miner, only to sue him to the tune of $50,000 for breach of promise. She won the case and an award of $1,250; the trial made her famous.

Soon she modeled for a memorial statue to President William McKinley, who had been assassinated the year before by anarchist Leon Czolgosz. Adolph Spreckels, son of sugar baron Claus Spreckels, who had made his fortune in Hawaii, was chairman of the selection committee. Alma's lightly draped form is still on view atop the Dewey monument erected in Union Square to celebrate the American fleet's victory at Manila Bay that spelled the end of the Spanish Empire and the beginning of the American domination of the Pacific.

Alma and Adolph began a long affair that culminated in marriage in 1908. In 1913, architect George Applegarth, trained at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, built her a splendid neoclassical mansion on Washington Street in Pacific Heights (the house, now owned by novelist Danielle Steele, was based on the Petit Trianon at Versailles). During her 1914 shopping expedition to France—the house needed filling up—Alma met the expatriate modern dancer Loie Fuller, who then brought Rodin to her attention. This connection resulted in Rodin sculptures coming to San Francisco and Alma throwing herself into war-relief efforts on behalf of the French and Belgians, despite Spreckels' family sympathy for Germany.

In 1915, Alma persuaded the French to participate in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in the teeth of war. Architect Henri Guillaume based the French pavilion on the Palais de la Légion dHonneur on Rue de Bellechasse in Paris. In three month's time, he produced a three-quarter-scale model to display a selection of Rodin sculptures.

Interestingly, the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur is itself a reproduction; the original building was constructed in 1788 just before the "Revolutionas" a nobleman's townhouse, the Hôtel de Salm. Even though M. de Salm was a partisan of the Revolution, he did not escape the guillotine. Nor did his palace escape falling into the hands of an unscrupulous wig-maker assistant who had acquired a suspect fortune!

In 1804, Napoleon, the Stalin of the French Revolution, “repurposed” the building as the headquarters for his recently created Légion, a substitute aristocracy meant “to bring together all the partisans of the Revolution.” The Légion survived as an arm of the French state through successive governments, none of them revolutionary; this fact was not lost on the communards of 1871, who set fire to the Palais de la Légion dHonneur as government troops retook Paris at the close of the Franco-Prussian War. As part of the restoration of order, which included shooting thousands of revolutionaries and putting the Vendôme column back on its pedestal whence it had been toppled with Gustave Courbet's assistance, in 1878 a replica of the Palais was built on the original site. It was this recreated building, triply a symbol of counterrevolution (ancien régime, Empire, post-Commune governments), that Guillaume copied for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

Thus, when Alma decided to base the design of her museum on the French pavilion of the PPIE, her building was fated to be a copy of a copy of a copy with complex links to her own history as well as to her present interests. The French Revolution made the Hôtel de Salm available to Napoleon, usurper of the Revolution and creator of the Empire, at the same time it provoked the flight of Alma's ancestor, General Louis Claude de Bretteville, to Denmark, making Alma, absolutely an original, available to San Francisco at a time when the city imagined itself as “the Paris of the Pacific,” the capital of the Pacific Rim.

If Alma was enthusiastic about the war and if much of the business elite supported American intervention against Germany out of sympathy for the French and with an eye on profits, this was not the case for many San Franciscans. The Spreckels family was officially neutral (being explicitly pro-German was ill-advised). Local working-class, socialist, and anarchist militants saw the war as detrimental to their interests, as did their comrades across the nation. As the PPIE closed in early 1916, the city was deeply divided along class lines, with employers intent on forcing open shop rules on the waterfront. A summertime waterfront strike was decisively won by the employers on July 17, 1916. An already tense situation came to a head at the massive Preparedness Day parade on July 22, 1916, when a bomb went off at the corner of Steuart and Market Streets as 20,000 businessmen, professionals and veterans marched in support of American participation in the war. Nine were killed, forty injured.

Labor and the left--including Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman--had denounced the parade, whose organizing committee included the likes of bankers William H. Crocker and Herbert Fleishhacker, and M.H. de Young of the San Francisco Chronicle. Now the usual suspects--workers, socialists, and anarchists--were accused of the bombing. Of the five people arrested, two were rapidly convicted in rigged trials: Warren Billings was sentenced to life in prison, and Tom Mooney received the death penalty.

Generally, throughout the country labor was on the defensive and dissent was suppressed, as situation that only grew worse after American entry into the war in 1917. When President Wilson declared his intention of making the world “safe for democracy,” the phrase was widely understood by businessmen and their opponents as code for making the world safe for American business.

Official suppression of dissent was often coupled with mob violence against people suspected of disloyalty. German-Americans, religious pacifists, union organizers, and left-wing militants were routine targets. Socialist leader Eugene Debs was sentenced to ten years in prison for lecturing on the economic causes of the war. Hamburgers were renamed “liberty sandwiches.” Vigilantes and law-enforcement officers fought pitched battles with the anarcho-syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World.

If anything, things turned worse at war's end. Strike waves and the Bolshevik Revolution triggered a Red Scare that culminated in the arrests of thousands and the deportation of hundreds of foreign-born radicals, including Emma Goldman. The same period saw a dramatic rise in lynchings and other violence against black Americans.

Against this background of intense social and political reaction, Alma continued planning her art museum. Groundbreaking was delayed until 1921 because of wartime shortages, but this didn't prevent Alma from arranging a visit to the construction site first by Supreme Allied Commander Ferdinand Foch and then, a few months later, by Marshal Joseph Joffre. These First World War generals were also veterans of the Franco-Prussian War, which triggered the Paris Commune, whose defenders had destroyed the original Palais de Légion d'Honneur. Finally, on Armistice Day 1924, George Applegarth's version of the Palais, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor (perhaps the name commemorated Alma's induction into the French Légion for her war-relief work) was ceremoniously handed over to the City of San Francisco.

However derivative the form of the building, Applegarth used modern methods in the construction of the museum. The reinforced concrete walls were left hollow to regulate temperatures, and the heating and ventilation system eliminated radiators and filtered the air. Applegarth's building also has a distinctive relationship to its site and setting: this Palace of the Legion of Honor stands in a bucolic setting radically different from the close urban site of the first replica on Rue de Bellechasse. And the entire structure is rotated 180 degrees, so that Applegarth's rendering of the street-side façade of the Paris building turns away from most visitors. There's not even a service door to be seen. Instead, a decorated wall faces in the general direction of Hawaii, the source of the Spreckels' fortune. Because Adolph died before the buildings completion, the Palace of the Legion of Honor is also dedicated to him; the averted façade seems mute acknowledgment as well as repression of the role his money played in its construction.

Alma de Bretteville Spreckels' collection reflected her conservative and at times bizarre tastes in art, appropriate for a social climber who married into the provincial bourgeoisie. No works by the likes of Picasso, Schwitters, Malevich or Ernst. As Alma put it, “The screwy art of today is done on purpose . . . to make the people miserable and dissatisfied.” Instead, visitors saw animal sculptures by local artist Arthur Putnam, Gobelins' tapestries, Sèvres porcelain, French furniture, and a number of objects “from the workshop of.”

Especially appreciated were donations by royalty, including Alma and Loie Fullers' old friend, Marie, Queen of Romania. The galleries of the Palace of the Legion of Honor would make her and the people she wanted to please and impress happy (one doubts that “the people” in the democratic sense entered into Alma's thoughts). By and large, the collection, with the exception of the Rodins, which remain explosive, memorialized the old order of Europe, specifically of Alma's fantasy of a prewar Europe of monarchy, old families, and established hierarchies. Even if San Francisco society still viewed Alma as an uncouth arriviste and gold digger, European society appeared to confer legitimacy on her claims to aristocracy.

In later years, the collection expanded in more interesting directions, and the museum has even hosted Picasso exhibitions and a major Surrealist show. The demographics of museum visitors have also shifted: like other museums around the world, the Palace of the Legion of Honor is no longer genteelly unfrequented by the rich or the studious. In Alfred Hitchcock's 1958 film, Vertigo, “Madeleine” (Kim Novak) is able to gaze transfixed and quite alone at the portrait of “Carlota Valdes” in one of the Legion's galleries. Nowadays, she would be jostled by crowds with timed tickets to a blockbuster show in hand or ejected by security-conscious guards. One could imagine Alma trying to take back her gift. . . .

But there's no going back on the gift, on time, on the times. Alma and the Palace of the Legion of Honor were embedded in history from the start. Personal quirks were inextricably woven into panoramas of revolution and restoration, war and class struggle, dispossession and expropriation. The building and the artworks it contains were intended to honor the dead who fell in a war that shattered the warrior code as it shattered the civilization that called young men to the defense of empire and business profits. The war brought down the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires; it provoked the Russian Revolution and revolutionary attempts in Germany and Hungary; it established American power in Europe.

In Alma's beloved France, the war discredited the old regime, the Fochs and Joffres who had the blood of millions on their hands. In Europe, disgust with the war and its aftermath was almost universal, and that disgust sharpened the critical edge of the modernist art that so annoyed Alma and the art-lovers of Pacific Heights. The Palace of the Legion of Honor belongs to a subgenre of memorials, to which most traditional memorials belong: these are memorials to the triumph of motivated forgetting. They repress disturbing contents and conflicts as they preserve a lifeless image.

In the early 1990s the museum underwent considerable renovation. The operation included seismic upgrading and massive expansion of the underground portion of the museum to include new work areas and a new restaurant. Excavation uncovered a grisly secret: the Palace of the Legion of Honor had been built atop the unmarked graves of a nineteenth-century potters field. More than 750 graves remained from a cemetery that was supposed to have been relocated to Colma a hundred years before. “It is speculated that Golden Gate Cemetery was in fact never relocated, but instead the headstones were simply removed, leaving the burials for future generations to deal with.” In a final irony, Alma made good her escape from an impoverished childhood in the dunes, but even her proudest accomplishment remains haunted by the poor.

— James Brook

My account of the facts of Alma Spreckels' life relies on Bernice Scharlach, Big Alma: San Francisco's Alma Spreckels (San Francisco: Scottwall, 1995).

Ibid., p 9.

Maurice Colinon, “Un palais pour un perruquier,” in François Caradec and Jean-Robert Masson, eds., Guide de Paris mystérieux (Paris: Editions Tchou, 1985), pp. 9697.

Napoleon quoted in Georges Lefebvre, Napoleon: From 18 Brumaire to Tilsit 17991807 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), p 150. For “partisans of the Revolution” read “supporters of Napoleon.”

This account relies on William Issel and Robert W. Cherny, San Francisco 1865-1932: Power, Politics, and Urban Development 178.

Scharlach, Big Alma, p 119.

YOU ARE HERE (YOU THINK)*: A SAN FRANCISCO BUS TOUR

The Palace of the Legion of Honor was a gift of Alma de Brettville Spreckels in 1922. Conceived as a 3/4 size replica of the Hotel de Siam in Paris, it serves as a memorial to the California soldiers killed in the First World War. The building is surrounded by wind-swept trees and a golf course on the bluffs overlooking the outermost corner of the Golden Gate. There are views of the Golden Gate Bridge, the Marin Headlands, and the northern part of the city. Below the sheer cliffs are nude beaches, ruined roads, and paths created by people in their search for golf and empty space.

View of Golden Gate from Palace of Legion of Honor

Photo: Chris Carlsson

When excavation began in the courtyard (beneath Rodin's "Thinker") some archaeological remains were anticipated, although the extent of the finds was both a surprise and a problem. It seems that the palatial memorial to the dead had been built directly atop the graves of paupers from the Gold Rush era. Bodies of gold diggers from all over the world were interred here. These earliest settlers had been buried in the San Francisco Cemetery and were moved to Lincoln Park (the site of the Palace) in the 1870's to make room for the burgeoning city. In 1909 the graves were supposed to have been moved again to Colma to make way for a golf course, but most of the graves were never moved--the markers had simply been kicked over and covered with dirt.

Palace of Legion of Honor excavation with bodies.

Photo: Provenance unknown

When the Palace was built in 1922, its foundation was poured on the redwood coffins of the city's pioneers. Would-be nude bathers routinely find headstones and markers in the gullies that lead down to China Beach. Every time there is any construction human skeletons will appear.

About 800 bodies were recovered while thousands more remain, some as backfill against the walls of the new museum cafe. The opportunity for discoveries about life in early San Francisco was immense and there was even the possibility of identifying some remains. But the rainy season was approaching and further archaeological removal of bodies was consuming time. After months of supporting the archaeology the coroner suddenly cut it off. Bodies were rushed off to Colma without detailed study, and field notes and photos from the dig were confiscated by the Museum. Only a cursory analysis of the immense store of knowledge has been undertaken to date.

The Museum took the project out of the hands of the archaeologist, even disallowing a private fundraising effort proposed by the archaeological team. Why was this research stopped and the affair covered up? One answer lies in the legal minefield of obligations that the identification of any bodies might lead to.

Influential and wealthy families setting out to build memorials to themselves faced wildly escalating costs brought on by the dead. If these had been the bodies of the wealthy with important descendants, would they have been treated differently? This new rush to ship off the bodies mirrors the original disinterment and successive cover-ups of 1909--when the bodies weren't moved--and the construction of the museum on their coffins in 1922.

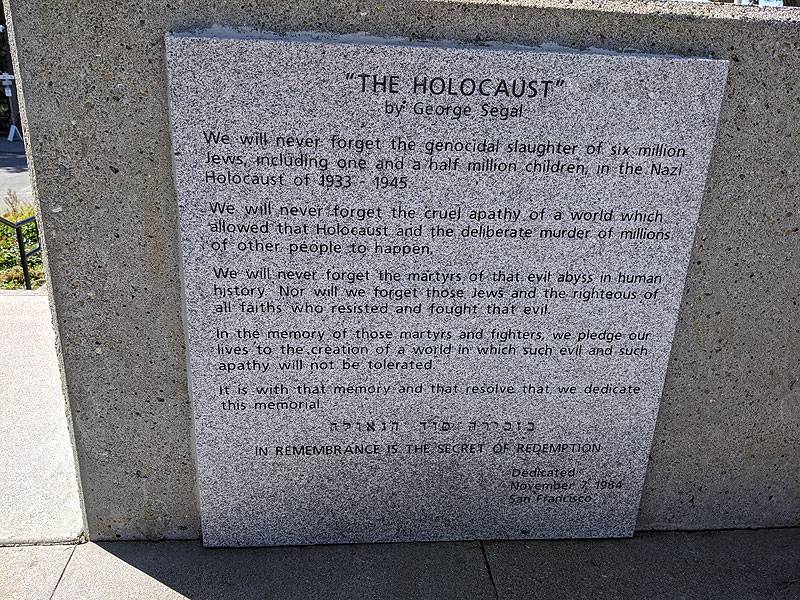

There is even more death around this peaceful hillside. Across the road, tastefully hidden below a corner of the parking circle in the sweep of a 270-degree turn with vistas of the ocean to distract your vision, is a poignant holocaust memorial by George Segal.

Holocaust Memorial adjacent to Palace of Legion of Honor parking lot, overlooking Golden Gate

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Explanatory plaque

--from "YOU ARE HERE (YOU THINK)*: A SAN FRANCISCO BUS TOUR: A reflection by Bernie Lubell, Dean MacCannell, and Juliet Flower MacCannell" in City Lights Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture January 1998.