Ecology Emerges 1970s

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Listen to an excerpt from "Ecology Emerges" read by author Chris Carlsson:

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/24TenYears--ecologyEmerges" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

by mp3.

![]()

Previous stop: Bernal Heights life in the 1970s

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/EcologyEmergesEvolutionOfEco-activism" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

View towards Mt. Davidson from south peak of Twin Peaks, April 2011. Both hilltops have been preserved thanks in part to the Open Space Fund that started in a 1974 election.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

“There’s no such thing as environmental victories, there are only holding actions.”

—David Brower

Just a half century ago, ecology as we know it was relatively unknown to the general population. An incredible range of activities and issues is encompassed by today’s ecological movement, from toxic waste remediation, clean water, renewable energy and sustainable transport, habitat restoration and species preservation, to the burgeoning healthy, organic food movement, and much more. The recent arc of human engagement with the environment can be traced from early-to-mid 20th century conservationists focused on wilderness and preservation efforts through 1970s mainstream environmentalists who tried to reform the worst practices of polluters and nature exploiters, to radical ecologists who began to question progress and developed an uncompromising biocentric philosophy, all the way to today’s biological diversity and environmental justice proponents.

The ecology movement emerged from a strange soup of 20th century antecedents and a concentration of specific historical events from 1968-78. By no means was it new in the late 1960s to be concerned about nature and the environment, though it was still unusual to use the expression “environmentalist,” and even less likely to call someone an “ecologist.” Before the word “ecology” gained prominence in the 1970s, defenders of non-human species and wild lands were generally known as conservationists, and they saw their work as essentially apolitical. Such folks were often from wealthier backgrounds, often able to contact politicians and decision-makers and have their opinions listened to. The class background of 20th century conservationists kept it a largely white, patrician movement during most of the century.(1)

The class orientation began to shift after the Save the Bay campaign of the early 1960s, which was led by three women, Esther Gullick, Sylvia McLaughlin, and Kay Kerr, who at the outset, reinforced the upper class origins of environmental campaigns (all had husbands who were University of California men—the president, the head of the Regents, and a professor). Starting as a conservation campaign to stop filling the bay in Berkeley, it became a region-wide effort that ultimately succeeded in getting a new state agency to take control over development on bay shores. The Save the Bay movement remains a monumental turning point in Bay Area history and the environmental movement, but it wasn’t an isolated phenomenon, coming as it did in the wake of a contentious battle over siting a nuclear power plant on the Sonoma County coast in Bodega Bay, and a widespread citizen revolt against new freeways in San Francisco, both in the late 1950s and early 1960s. All of these efforts tapped a broad population to pressure elected officials against blindly going forward with palpably bad development projects.

A ubiquitous ecological activist since the 1980s, San Francisco’s Ruth Gravanis emphasizes the important role Save the Bay played in debunking the notion that strict regulation of shorelines and bay fill would wreck the regional economy. Many people who would later be part of the emergent ecology movement met each other at Save the Bay meetings. Save the Bay also demonstrated a new way to do environmental politics. “Save the Bay and the Bay Conservation and Development Commission [BCDC] were the models of advocacy organization and institution,” explains Larry Orman,(2) longtime director of the Greenbelt Alliance, which started as a conservation organization in 1958 under the name Citizens for Regional Recreation and Parks (meeting at Dorothy Erskine’s home on Telegraph Hill) and in 1969 renamed People for Open Space.

Environmental groups started springing up like mushrooms after a rain, but it was a rain of bad news. Historian Warren J. Belasco captures the time, “The environmental crises peaked in 1969, when an oil spill off Santa Barbara fouled beaches and killed birds, a smog alert paralyzed Los Angeles, and Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River caught fire. On top of this came a rash of news stories on DDT, cyclamates, soil erosion, world hunger, and warnings of impending earthquakes and tidal waves.”(3) By the late 1960s, ecological politics started to move beyond earlier concerns for open space and parks to address urban issues from garbage, pollution, and toxic waste, to questions of food safety, energy production, and transportation, all deeply affecting a quality of life profoundly dependent on air, water, and food. Former San Francisco Digger Judy Goldhaft says, “We were into living in a more harmonious way with the planet right from the mid-’60s. There was natural medicine, natural childbirth, organic foods, sustainable living.”

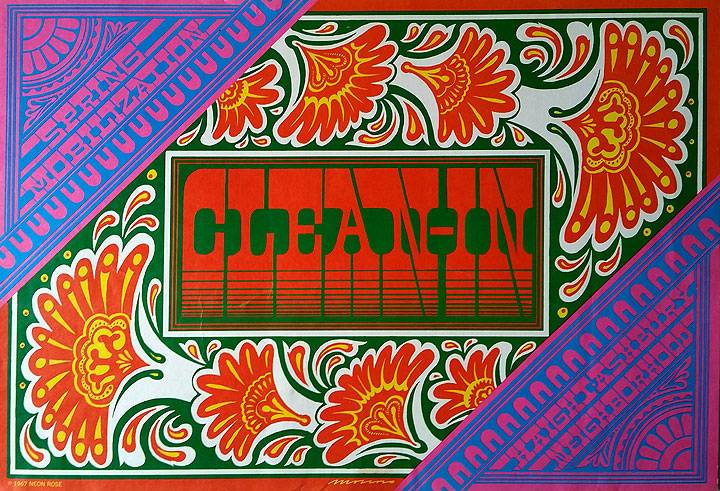

Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood "Clean-In" during Spring 1967 mobilization.

Image: courtesy Eric Noble

Democracy Evolving

At decade’s end there was also a widespread sense of imminent social revolution. As illustrated in other articles in this volume, upheavals were taking place in every area of life, from domestic roles and sexual behavior to the anti-Vietnam War movement, civil rights and urban insurrection, to university strikes and factory wildcats. Insurgencies were breaking out everywhere, and it was only logical that the revolt against “The Man” at work, at school, and in the streets, also would begin to express itself in a rejection of the toxified environment on which modern life depended.

Bill Evers, who had been a founder of the mainstream California Planning & Conservation League in the mid-1960s, and became a longtime board member of the Greenbelt Alliance, found himself surprised at the new kind of politics that had erupted in the streets: “I did not ever envision [protesting in public]. I thought it could even be counterproductive, offend people. They’d say ‘that’s not how democracy works. If you gotta gripe, vote another guy into office.’ But I think the demonstrators have proven the value of it, in at least getting people to focus on the problem. It’s crude democracy, but it is democracy.”(4)

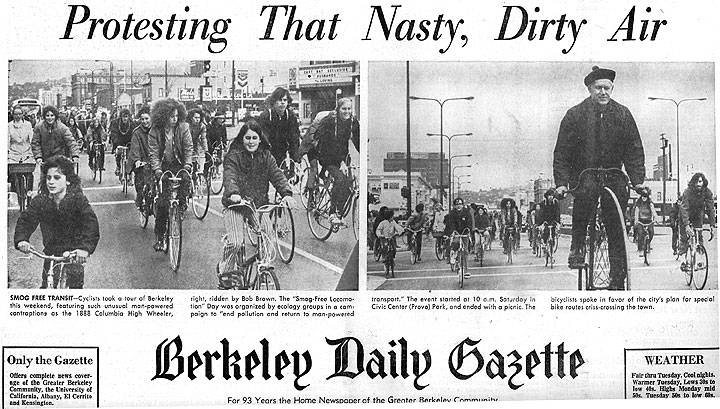

In the fall of 1968, the Whole Earth Catalogue was published, featuring on its cover the first widely disseminated view of Earth from space. It had a galvanizing effect on many people, and gave a major boost to seeing the interconnectedness of life on Earth. Barbara Korr writes in the San Francisco Good Times underground newspaper of October 2, 1969, “We look around and see everywhere the plastic encroachment of the unreal on the natural. In the ecological view man is a member of a community which includes plants and animals—all the forms of life—and when the delicate strands of our mutual interdependence are destroyed or tampered with the result is a ravaged land and a ravaged people.” She was reporting on a Civic Center exhibit put on by Ecology Action, a group that was the ecology caucus within the Peace & Freedom Party, but which also started as an independent group. In 1969 they sponsored many events, including a “Smog-free Locomotion Day” on September 28 (a big bike ride through downtown Berkeley that looks a lot like a contemporary Critical Mass ride), an event that repeated itself in following years.

Long before Critical Mass rides started in the early 1990s, an earlier wave of ecology-minded folks cycled en masse through the streets of Berkeley in an annual "Smog-Free Locomotion Day, this one held February 28, 1971.

The first Earth Day was held in spring 1970. Given the brutal war being escalated at the time in Southeast Asia, and the urban and campus revolts that were still underway (or at least very recent experiences), the government needed to channel this public clamor into a process. The emergent concern for the environment gave the US government an arena to proactively address a rising public demand for action. In his recent book The Rebirth of Environmentalism, Douglas Bevington handily summarizes the flurry of activity:

Following the first Earth Day in 1970, there was a burst of federal legislation on environmental protection. Twenty-three major environmental laws were enacted during the decade of the 1970s, including the National Environmental Protection Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the National Forest Management Act. … This environmental legislation is often presented as one of the foremost accomplishments of the national environmental organizations and as a reflection of their political clout following Earth Day. However, closer examination of the legislative history reveals that the dominant national environmental organizations played relatively minor (and at times even counterproductive) roles in the passage of these laws. (5)

The National Environmental Protection Act, passed prior to Earth Day after little debate in Congress by huge majorities in both houses, was signed by President Nixon in January 1970. It created the President’s Council on Environmental Quality and required for the first time an Environmental Impact Statement for every major federal project. Bevington reports that it provided “substantially increased opportunities for public participation in agency policy making, both by creating a detailed public record of environmental impacts and also by providing for increased public input and oversight.”(6)

Only a decade earlier, Doris Sloan (who in 1975 took the helm of the fledgling UC Department of Environmental Sciences) had attended Sonoma County Board of Supervisors meetings as an activated housewife, only to find the officials sitting with their backs to the unexpected audience. As deliberations took place over PG&E’s proposed nuclear power plant in Bodega on the Sonoma County coast, there was no expectation of citizen participation, and the physical layout of government meetings reinforced the closed nature of the process. In 1970 the democratic surge outside of official channels would be given a seat at the table, at least with pre-arranged limits that reinforced who the real power holders were.

Grassroots activism flourished and provided the public foundation for a challenge to scientific expertise, given impetus by the failure of establishment science to question the uses to which it was put. “Experts” pushed chemicals and chemical warfare, nuclear power, more freeways, increasingly industrialized agricultural systems, and so on. Opposition to the juggernaut of ecological destruction could only come from an emboldened citizenry, one that had learned to think and speak for itself. Karen Pickett was working at the Ecology Center in Berkeley in the mid-1970s, and she remembers “people feeling that even if they weren’t a scientist or an attorney they could go and testify at a BCDC hearing. Even if they didn’t have all the answers they could produce and distribute a factsheet or a booklet on something that people needed to know.”

An influential figure that is not often credited with shaping the modern environmental movement is Saul Alinsky, the author of the 1971 Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals.(7) He inspired Ralph Nader and Cesar Chavez, to name but two of the many important figures who learned about community organizing from Alinsky. Nader of course went on to establish a wide variety of public interest organizations, often addressing consumer safety and health issues, an early type of pre-environmental organizing. But Chavez would use the door-to-door and house meeting techniques he learned as a member of the Community Services Organization, a group affiliated with Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, to found the United Farm Workers Union.

Chavez put together an unprecedented alliance with environmental groups and consumers. The national grape boycott went on for several years before California growers gave in and signed union contracts in 1970-71. What is less remembered from that period was the agitation going on in supermarket parking lots on behalf of the grape boycott that educated middle- and working-class shoppers about the severe problem of pesticides on food. The farm workers were being contaminated by DDT and similar poisons (made infamous by Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring). Historian Robert Gordon summarizes Chavez’s new awareness:

Recognizing the potential appeal of a fight to protect workers, consumers, and the environment, Chavez stated that ‘the issue of the health and safety of farm workers in California and throughout the US is the single most important issue facing the United Farm Workers Union…We have come to realize… that the issue of pesticide poisoning is more important today than even wages.’(8)

With boycotts and a lawsuit filed in collaboration with the early Environmental Defense Fund and California Rural Legal Assistance, the UFW was instrumental in getting DDT banned nationally. Growers began replacing those chemicals with organophosphates (many agricultural pests were developing immunity to DDT by then) but the new pesticides were even more toxic to the workers, albeit quicker to break down in the environment. Because of this, some mainstream environmentalist organizations kept the UFW at arm’s length. But the UFW/EDF alliance, though short-lived, was one example of a broad alliance between environmentalists and labor at the start of the 1970s. Emerging out of the battles to pass the Coal Mine Safety and Health Act (1969), the Occupational Safety and Health Act (1970), and the National Environmental Protection Act (1970), rank-and-file workers along with progressive union and environmental activists, realized that hazardous working conditions, workplace pollution, and the deterioration of the natural environment were closely related.

It’s telling that the United Autoworkers, United Steelworkers, United Mineworkers, Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers, and the International Association of Machinists, worked closely with the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth, Environmental Action, and others to pass many new laws during the early 1970s. Little wonder that there was so little opposition expressed in Congress given the broad alliance pushing these changes. Perhaps it is also not surprising that the successful alliance of the time was soon torn asunder by the divergent politics that followed the oil price shock and the severe recession of the mid-1970s.(9)

War is Ecocide

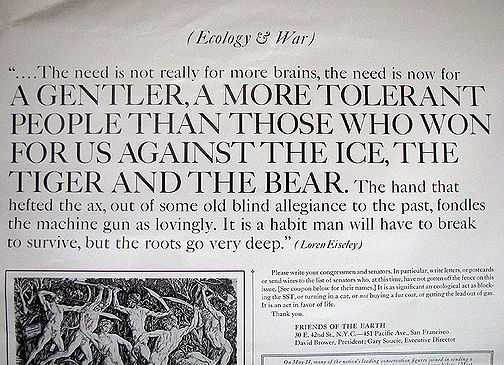

Massive anti-war demonstrations from 1967-1972 were the cauldron in which the modern environmental movement was forged. The devastation inflicted on Vietnam and Southeast Asia through massive bombardment and an unprecedented use of chemical warfare against nature itself in the region, inspired much direct opposition, but also shaped a new awareness of ecology. Here are excerpts from an open letter by Friends of the Earth in support of a telegram sent to President Nixon by dozens of environmental leaders in 1970:

Ecology & War

This advertisement is being placed by Friends of the Earth, a conservation group, but it concerns the war in Southeast Asia, and also wars in general.

Until recently conservationists have been thought of as content to fight the tragedy of a dam, the outrage of pollution, the spread of ugliness and environmental degradation, and also the economic and political solutions to that sort of mindless destruction.

Wars have been someone else’s problem.

It has been as though war is not as destructive as dams. Or that an air pollution hazard in Los Angeles is a more significant danger to life than bombs landing upon non-combatants in a war, or the laterizing (turning to rock) of thousands of square miles of formerly living soil by widespread use of napalm. It is as though DDT in our vital tissues is worse than wartime chemical defoliants in the tissues of pregnant women.

It is not true. They are all of equal order, deriving as they do from a mentality which places all life and its vital sources in a position secondary to politics or power or profit.

Ecology teaches us that everything, everything is irrevocably connected. Whatever affects life in one place—any form of life, including people—affects other life elsewhere.

DDT on American farms, finds its way to Antarctic penguins.

Pollution in a trout stream eventually pollutes the ocean.

Smog over London blows over to Sweden.

An A-bomb explosion spreads radiation everywhere.

The movement of a dislodged, hungry, war torn population affects conditions and life wherever they go.

It is all connected. The doing of an act against life in one place is the doing of it everywhere. Thinking of things in any other way is like assuming it is possible to tear one stitch in a blanket without unraveling the blanket.

Friends of the Earth, therefore, its Board of Directors and staff, wishes to go on record in unanimous support of the recent telegram to Mr. Nixon, signed by the leaders of the nation’s conservation organizations.

The ecology-war connection goes back to the original A-bombs dropped on Japan, of course, and the 1950s campaign to end atmospheric nuclear testing. Anti-nuclear campaigning in that era was largely led by pacifists and religious organizations, especially the American Friends Service Committee of the Quakers. The spread of radioactive fallout around the planet, overwhelmingly produced by US nuclear testing, inflamed world opinion and led to the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, signed by President Kennedy in 1963 (it banned nuclear testing in the atmosphere, underwater or in space), though it was never signed by France or China.

Few remember now that Greenpeace was founded in 1970 in Vancouver, Canada to protest the US government’s testing of nuclear weapons in the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. For the organization’s first five years, its activities focused entirely on combating nuclear testing. Saul Bloom, a San Francisco social justice activist, founder of ARC/Ecology, and long-time ecologist joined Greenpeace in 1977 and worked for the organization for six years. He remembers, “The folks who founded Greenpeace understood the connections between environment, war and peace, and the media—that was fascinating stuff at the time.”

Greenpeace, like a number of other groups in the mid-1970s, embarked on an ambitious program of door-to-door canvassing,(10) which Bloom managed during 1977-78 before eventually becoming a Regional Director.(11) Bloom moved on from Greenpeace in 1983, in part because of differences over organizing philosophies and in part because of disputes over the relative toxicity and damage caused by nuclear vs. conventional weapons systems. Still, the overarching focus was on the military’s role in ecological damage, maintaining the important relationship between eco-activism and anti-militarism that was given such impetus during the anti-Vietnam War movement.

Another slightly later example of the abiding connections between environmental activism and anti-war campaigning emerged in the wake of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua in 1979.(12) When Reagan launched his illegal Contra War against the Nicaraguan government, a group was formed called Environmentalists for Nicaragua, sponsored by the fledgling Earth Island Institute in 1982. Later and better-known as EPOCA, the Environmental Project on Central America, co-founder Dave Henson describes their mission, “We were talking about an effort to connect poverty, war, and the environment in a Sandinista-led Central American country.”

Atomic Power and Chemicals: Energy and Food

Atomic power and chemicals were two overarching symbols of progress in the post-World War II modern world. The “peaceful atom” was heavily marketed to justify the US’s enthusiastic embrace of the nuclear genie for war, while the chemical industry was promoting itself as a cornerstone of improved lifestyles (“better living through chemistry” was one marketing slogan of the time). Both of these state-of-the-art technologies underwent recasting during the late 1960s. The peaceful atom came under sharp attack from many quarters, while the public relations campaign of the chemical industry to tout its “green revolution” in agriculture began to erode under the pressure of counter narratives produced by anti-war activists on one hand, and health food proponents and farm worker organizers on the other. The unquestioned March of Progress had run firmly into a wall by 1970.

Silent Spring had started many people on a path away from agribusiness-dominated food supplies. The search for the natural was on. Belasco provides an excellent overview:

Venturing into a health food store in late 1968, San Francisco Express Times food advisor Barbara Garson assumed the manager would be another one of those ‘proverbial little old ladies in tennis shoes.’ Yet in explaining why Garson should not eat sugar, the manager recounted the sordid role of US refineries in Cuba since the turn of the century. Previously wary of health food ‘cults,’ Garson was pleased—and surprised—that honey, whole wheat, soy noodles, organic raw milk, unusual herbs, and other health food staples could have a progressive context. Other freak explorers of the health food underground reported similar discoveries: dusty copies of hard-to-find works by critics Adelle Davis, Beatrice Trum Hunter, and Rachel Carson—all dismissed as crackpots and cranks by mainstream authorities; and assorted pamphlets with utopian, spiritual, and dietary guidance. Writers of such advice commonly dismissed technocratic experts, worshiped nature, and tended to think in whole systems, not parts. In short, the health food stores offered holistic information that might be called protoecological.(13)

Orman built on this new food consciousness in the following decade. During the mid-1970s, he devised a public campaign to preserve agricultural lands around the Bay Area, arguing for them on food security grounds as well as open space/eco-habitat grounds. He realized that in trying to sharpen the boundaries between urban, suburban, and rural, farmlands were a vital and vulnerable component. His organization People for Open Space, produced a Farmland and Conservation Study of the whole Bay Area. He explains, “Food, food shed, that was my thing and I pushed that along. I don’t care if it’s organic or commercial. It’s important for people to be connected to their local agriculture.”(14)

Goldhaft joined with other Digger women in San Francisco to find a new relationship to food. “For me ecological consciousness is involved also with food production. I went to the wholesale produce markets and learned where all the vegetables came from. We became friendly with a number of the people there. We got a lot of produce that was going to be discarded which was essentially extremely ripe produce that was ready to eat, but wouldn’t hold on the shelves. At about the same time we were also invited to glean fields around Half Moon Bay. We also were given so many donations that I learned how to do canning and preserving of various kinds, because we had to. Either we had to give the food away, or find some way to preserve it.”

Local agriculture was the antithesis of what was happening in the food business. In the 1970s, major grocery chains were consolidating their hold on the national food market. Local grocers and small chains were being gobbled up by Safeway, A&P, Krogers, and Lucky.(15) The march of homogenization was flattening diversity, making food tasteless, and saturating consumers with chemical-laden food. Thousands of people were dropping out and heading to the country in pursuit of a more “natural” life. Goldhaft went to a remote California commune near the Oregon border. “When people left the city and began settling outside, the ‘hippies,’ the back-to-the-land people, were very involved in sustainability and healthy eating, not eating food that was pesticided, preferring organic growing.” This pursuit of self-reliance didn’t always work out as planned, but in general a lot of folks established a new relationship with food, and usually with technology more broadly.(16) A return to artisanship was also fueled by the new embrace of “natural.”

Ecological campaigns were seeded in that first wave migration to the country. Those who retained a political approach turned themselves toward combating nuclear power, one of the most overwrought and self-defeating technologies ever invented. In later years many of these same activists, now much older, would be involved in the timber wars, river restoration campaigns, toxic waste and environmental justice struggles, and more. Barbara Epstein wrote an excellent history of the “nonviolent direct action anti-nuclear and peace movements” and nicely reconnects the anti-war movement’s back-to-the-land exodus with the next wave of ecological activism:

By the early seventies, the focus of the left counterculture had shifted to the countryside. Many of the people who had made up the countercultural wing of the antiwar movement were moving to rural areas in northern New England, Northern California, and elsewhere to construct communities where they hoped to live their values and perhaps begin to build a movement expressive of them… The counterculture’s use of guerrilla theater and other forms of creative expression, its lack of interest in the conventional political arena, its emphasis on the creation of alternative communities, all suggested that revolution had more to do with thinking and living differently, and convincing others to make similar changes, than with seizing power.(17)

In California the anti-nuclear movement had been growing for many years. Doris Sloan was one of the residents of the small apple-farming town of Sebastopol in Sonoma County who joined the effort to stop PG&E from building a nuclear power plant on the Pacific coast at Bodega Head (the struggle lasted from 1958-1963). Her proto-ecological opposition was informed by her sympathetic support for the anti-atmospheric testing movement, which had begun to demonstrate the health hazards of radioactive fallout. She recalls that she and her fellow Sonoma County citizens trying to stop the PG&E nuclear power plant did not identify themselves as conservationists or by any particular label. “We just saw ourselves as a small group of people battling for safety and aesthetic reasons. We were just a bunch of people battling PG&E because we didn’t think there should be a nuclear plant on the San Andreas Fault, y’know?!” PG&E was eventually stopped, but not before digging a big hole at Bodega Head, which at present day is an oceanside lagoon.

The Diablo Canyon controversy started in 1963 when PG&E gave up trying to build the Bodega reactor. Rather than face similar public opposition at Diablo Canyon, PG&E approached the Sierra Club’s president and cut a deal with certain board members where Diablo would be chosen rather than the Nipomo Dunes area, which PG&E had originally chosen. The Sierra Club president forbade any chapter from opposing Diablo Canyon, so the San Luis Obispo Chapter formed the Shoreline Preservation Conference to oppose the construction on the grounds that the area had been proposed as a state park, was a sacred Chumash Indian site, had some of the largest oak trees on the West Coast, was located on the second to last coastal wilderness area in California, and was very likely sitting on the fault that destroyed Santa Barbara in a 1927 earthquake.(18)

After the oil shock of 1974, nuclear development in California was getting new support. In 1974-1975 Alvin Duskin, who played an important role in San Francisco and California environmental politics (he had funded a successful public relations campaign against the first Peripheral Canal plans in 1970, and organized hundreds of San Franciscan voters into a grassroots campaign against high-rises, popularly known as the effort to stop the Manhattanization of San Francisco),(19) was involved in funding and organizing a statewide ballot proposition to ban nuclear power plant construction. The vote was slated for November 1975, and this author and many other young college students spent weeks handing out literature in shopping center parking lots and campaigning on campuses and in neighborhoods. PG&E was pressing ahead with plans to build Diablo Canyon, while Southern California Edison was promoting Sundesert, and an additional reactor at San Onofre. Duskin explains his role in this forgotten saga:

I worked with Another Mother for Peace in getting this thing [Prop 15] on the ballot, the people in San Luis Obispo, fighting Diablo Canyon and all that. We stopped Sundesert. We stopped it. They’d spent money on it, Southern California Edison, they spent on San Onofre. We stopped that. We led to the decommissioning of the plant up in Eureka [in 1983]. [Proposition 15] said you can’t zone land in California for a nuclear power plant until you can solve the problem of waste. And for existing plants after a year or two, if the problem of waste isn’t solved, the plant has to be de-rated by 5% each year. That would mean that Diablo Canyon and San Onofre would be eventually decommissioned. If they just keep losing 5% a year, it would make them uneconomic to operate.

Duskin was contacted by Sacramento legislators and agreed to help them write a law that would do everything his initiative was going to do, except the de-rating of existing plants. They sold it as the rational alternative to “Alvin Duskin’s radical, communistic, anarchistic, free-love initiative.”(20) When the legislature passed the bill a few weeks before the statewide vote, it successfully killed the anti-nuclear campaign and the initiative was defeated that November. Duskin remembers, “People were consoling me on the streets, saying ‘Alvin, I’m sorry that lost,’ and I said, ‘No, we’ve actually won! They’re not going to build any new nuclear power plants in California!’ ”

Diablo Canyon became the object of a six-year campaign of nonviolent action and full-court-press legal opposition from 1977-1983. Another Mother for Peace, along with dozens of new affinity groups and local organizations around California under the rubric of the Abalone Alliance,(21) campaigned against Diablo Canyon. The name Abalone Alliance referred to the tens of thousands of wild California Red Abalone that were killed in 1974 in Diablo Cove when the nuclear unit’s plumbing had its first hot flush. They carried out an escalating campaign of direct action in the attempt to stop the plant from opening. In August 1977, 1,500 people encircled the gates while 47 were arrested. A year later, 5,000 people came and almost 500 were arrested. When the Three Mile Island nuclear plant had a partial meltdown near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, an April 1979 rally drew 25,000 people to an anti-nuclear rally in San Francisco, followed by 40,000 demonstrators converging on San Luis Obispo for the largest anti-nuclear rally held at that point in US history. Their biggest effort came in autumn 1981 when 20,000 people rallied in support of a two-week blockade that led to 1,900 arrests. (Unfortunately the plant opened and having reached its predicted lifespan of 25 years, PG&E is now seeking an extension for its operating license.)

Recycling and NIMBY

On October 29, 1969, a computer lab at UCLA connected to computers at the Stanford Research Institute, and then continued to spread out and connect with computers across the planet, which was the beginning of the Internet. On a much smaller scale on the same day, a dozen activists had an appointment on Montgomery Street in downtown San Francisco with Horace Blinn, boss of the Pacific Division of the Continental Can Company, and also the head of the California Anti-Litter League. The demonstrators were from the Canyon League, Ecology Action, and the Free University of Berkeley’s Street Theatre Group. As they waited on the street, a crowd began to grow around them, and six barrels of empty cans appeared. After one man was arrested for littering when he refused to move the barrels, Jeremia Cahill of Canyon went in the door with a barrel to keep the appointment with Continental Can. The police pursued and forced him back out, whereupon he began a press conference. While everyone’s attention was captured, another small group of demonstrators made their way to the seventh floor only to find the entire Continental Can office closed for a funeral. Their simple questions went unanswered by the one guy present, “Why do you make a product that can only be used once and then has to be thrown away? Why don’t you make something that can be used over and over again, and stop stripping the world of its precious resources?”(22)

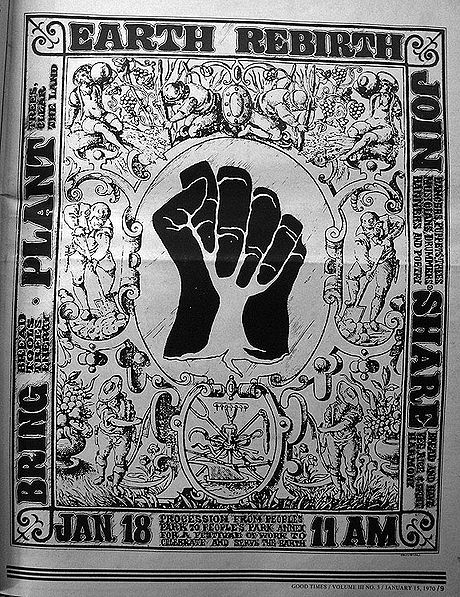

from Good Times of January 13, 1970.

The hypocrisy of the can company executive also being the head of the anti-litter campaign was not lost on the new ecology protesters. It wouldn’t be too long before recycling efforts began in earnest on both sides of the Bay. In Berkeley the Ecology Center was founded in 1970, and a major recycling center was opened that sparked a wholesale effort by thousands of local citizens to begin sorting and recycling their garbage.(23) A similar effort was undertaken in San Francisco: between 1970, when Richmond Environmental Action (REA) was founded, and 1979, when there had grown up a dozen or more individual recycling operations ranging from REA with a yard, equipment, and staff, to monthly paper drives by churches and scout troops. Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Council (HANC) Recycling was founded in 1974 and Bernal Recycling in 1977. Together these centers and programs attempted to apply neighborhood solutions to solid waste management.(24)

Pickett was an early staffer working as a recycler for the Berkeley Ecology Center. She remembers:

We went from working for a long time to get people to see the value in touching their garbage, and separating things. The whole idea was that if they participated in that process, then things would be reused in the highest and best use way. We separated colors of glass, never mind the glass from cans. [It’s] ironic that [since] it’s been institutionalized and it’s so acceptable that everybody is recycling, everything is thrown into the same bin.

Nowadays we have curbside recycling in San Francisco but few realize how that came to be. Sunset Scavenger likes to take the credit for it, but Ruth Gravanis was one of the activists who fought off a plan to build a trash incinerator just south of the city in Brisbane in the late 1980s. Had it been built, there would not be curbside recycling in San Francisco in 2010, “because we would be obliged by our contract to produce as much garbage as possible to burn as much as possible to generate electricity to sell to PG&E to pay for the trash burner!” It passed SF’s Board of Supervisors, Brisbane’s Planning Commission, and Brisbane’s City Council. “Thanks to the good citizens of Brisbane, who put a proposition on the ballot that stopped it, we didn’t get an incinerator. What a lot of people don’t know who talk about San Francisco’s zero waste, was that it was the NIMBYs of Brisbane who made it possible for us to have a curbside recycling program!”

The NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) phenomenon has coursed through environmental activism and fights over all kinds of development. The Brisbane refusal to host a garbage incinerator is a good example, but what NIMBY highlights is that some populations have the political clout to get their way when they refuse a development proposal, and others do not. Evers is enthusiastic (if class unconscious) about it: “You had a great ally in NIMBY. NIMBY was the greatest friend the Greenbelt ever had. The big transition in the Bay Area was when population increased to the point that people could see they had a problem. That’s when the urban boundaries were adopted by a vote in the communities,” arresting the pell-mell pace of urban sprawl, at least in the Bay Area.

The Roots of Biocentrism, Environmental Justice, Open Space

In the decades since the early 1970s, environmental activism has expanded, deepened, and subdivided into hundreds of efforts. As Orman notes, “the organizational ecology in the Bay Area is totally filled out.” In the early 1970s, “before the proliferation of environmental groups, the Ecology Center was where people were meeting each other,” recalls Pickett:

A lot of people got their start being turned on to other people, resources and ideas at the Ecology Center, and went on to do other things. The Ecology Center never ‘owned’ much of anything in terms of campaigns and issues, but was a resource and a springboard. A lot of the people that worked on styrofoam or plastics issues, or started community recycling centers, or brought projects into the schools, or started community garden groups, or creek restoration groups, wouldn’t necessarily credit the Ecology Center, because there was this general sharing of ideas without ownership, but if those seeds hadn’t been planted back then, I don’t think we’d be where we are now.

One of the galvanizing moments for the Ecology Center was the organizing done after the January 18, 1971 oil spill. The event itself “was so dramatic and horrifying that it just totally threw in people’s faces in a very big way what was happening,” says Pickett. Chevron’s Arizona Standard and the Oregon Standard collided beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, dumping over 800,000 gallons of crude oil into the Bay. Thousands of birds and other aquatic life were soaked in crude oil and volunteers mobilized immediately. Volunteer centers were set up in Richmond and at the San Francisco Zoo, where for two months hundreds of volunteers taught themselves how to clean oil from aquatic wildlife. “There was no place for the volunteers to come. People were horrified, people wanted to do something, people could do something, but there was nobody to coordinate that huge volunteer force. There would be today,” notes Pickett. Coming two years after the massive oil spill along the Santa Barbara coast in southern California, the ecological consequences of the car/oil economy were suddenly starkly apparent.

An important achievement of 1970s environmental activism in San Francisco, rarely remembered but one that many of us enjoy every day, is our open spaces and parks. Billed innocuously in the 1974 local election as a “Parks Measure,” San Francisco voters passed Proposition J on November 5 that year by 116,654 to 64,527. It added to the local property tax assessment, raising over $2.5 million per year to fund park improvement, but most crucially, acquisition of open space. The monies raised from this initiative since that time have gone a long way to preserving most of San Francisco’s hilltops as open space, opening new parks, saving remnant habitats, and providing public land for community gardens. It’s difficult to imagine how densely built out the urban environment would be had this initiative not passed at the peak of the first wave of environmental awareness and activism.(25)

A couple of owls made their home at the top of Esmeralda Steps in 2007 on the Bernal Heights ring road, a product of the open space acquisitions made possible by the 1974 Parks Measure.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Planet Drum co-founder and former San Francisco Digger Peter Berg has a different view of the environmental movement than most:

I think the environment movement as an interesting, engaging thing ended with Earth Day [in 1970] and the founding of the EPA. Mainstream environmentalists were stuffed shirts, careerists, anthropocentric. There was a lot of careerism, a lot of middle-class values. There was a whole other approach: to harmonize with natural systems, rather than protect or defend or whatever.

Planet Drum is a small San Francisco organization that grew out of a series of cross-country trips he and his partner Judy Goldhaft made, seeking out radical communities that had gone back to the land. Everywhere they traveled in 1970-71 they encountered groups living adjacent to environmental disasters, whether clear-cutting of forests, toxic waste-spewing factories, or plans to construct nuclear power plants. Traveling with a video camera, Berg made “video postcards” from each commune, ultimately sharing his work at the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Environment in Stockholm, Sweden. On their return to the Bay Area, Berg began working with conservationist Ray Dasmann,(26) who modeled an inquisitive and observational approach to nature that Berg took to heart. Dasmann and Berg spent many weeks driving around California together, visiting unique habitats and remote sites, giving Berg a crash course in California ecology. Later Berg adapted the concept of “bioregionalism” to reorient human politics on a biocentric basis, and Planet Drum began convening “continental bioregional gatherings.”

By 1978, Planet Drum had started a local gathering called the Frisco Bay Mussel Group that held regular meetings at The Farm,(27) bringing in various ecologists and activists to teach each other as much as they could about the local environment and the politics that shaped it. The Peripheral Canal was once again raising its head, with California politicians arguing over how to augment fresh water supplies for the southern part of the state by diverting it from the Sacramento River system and delta. It threatened to destroy the health of the San Francisco Bay.(28) The Frisco Bay Mussels gave Planet Drum impetus to borrow a commonly used tactic of the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth by taking out a full page ad in the San Francisco Chronicle, but this time, turning their successful technique against the mainstream ecology groups. The full-page ad denounced the canal plans, but also had coupons that readers could clip and send to the Sierra Club—urging them to reverse their support for the canal—and Friends of the Earth, urging them to take a firm stand against the canal instead of their then-neutral position. Both organizations were deluged with coupons and came out against the canal. Later Planet Drum founded a Green City effort in San Francisco, to promote bioregional thinking in the urban context. This led to the publication of a book full of practical transformational ideas for a more ecological urban life, many of which have since been implemented.(29)

David Brower was by all accounts one of the most important people in Bay Area ecological history. He led the Sierra Club for 17 years in which he led many high profile campaigns against dams and to save wilderness before arguments over politics, publishing, and priorities pushed him out. In 1969 he was ousted from the Sierra Club, and with core collaborators like Tom Turner and Jerry Mander, founded Friends of the Earth that September. Friends of the Earth immediately became a vital voice for all things ecological. Mander worked on the original ad campaigns in the mid-1960s against building dams in the Grand Canyon. He got to know Brower during that time, and went on to collaborate with him for many years. Moreover, Brower deeply influenced his thinking:

We’re embedded in the natural world, it all comes from that, all the resources, all wealth, all health, and if we’re not cognizant of that, it will die and we will die. It’s absurd to think of it any other way. Brower was my opening to this way of thinking. I didn’t hear ‘biocentric’ in those days. I heard ‘ecology’ from him, back in the early ’60s. He was already talking ‘no growth’ as a crucial element, that growth was the enemy of nature. That if we’re not aware of growth as the central issue we’re not going to succeed at saving the environment or saving the world.

Brower influenced everyone who came in contact with him, and anchored countless initiatives from the 1950s until his death in 2000. His own trajectory prefigures a larger transformation of the environmental movement, as he began as a mountain climber and outdoorsman, and when he became the first Executive Director of the Sierra Club in 1952, he focused his efforts on preserving wild lands slated for damming and industrial development. By the time he started Friends of the Earth, his prodigious talents were focused on specific issues like the Alaska oil pipeline, highway construction and private autos, the Supersonic Transport plan (SST, a competitor to Europe’s Concorde), nuclear power, forest clear-cutting, endangered species, and more. He was good at making alliances and effectively lobbied government at all levels. But as John Knox, director of the Earth Island Institute and long-time collaborator with Brower emphasizes, “[Brower] was kind of wild. Young people would bring him an idea, and he would become the public champion of the idea. He became a machine for listening carefully and getting excited about things that needed attention.” Underneath his enthusiasm and passion, a deeply critical thinker was always at work.

The reframing of urban ecological activism under the aegis of “environmental justice” since the early 1990s can be traced to an early 1970s turning point. When Brower left the Sierra Club and started Friends of the Earth, he and his colleagues could publish more radical writing than they’d been able to under the suspicious apolitical eyes of the Sierra Club Board of Directors.(30) Their new publication Not Man Apart sought to become a regular environmental news source, hoping to become a weekly or even a daily paper. On a shoestring budget, they did an incredible job of bringing to light themes that remain important today. In September 1971 they published an article called “Why Must We Choose Between the Environment and the Cities?” by Marion Edey, who was the Chairman of the League of Conservation Voters (which started out as a Friends of the Earth project but quickly moved out of the nonprofit umbrella to its own life as a directly political organization):

…The rats in the ghetto, the lead paint peeling from tenement walls, the overcrowding, air pollution and inadequate transportation that plague the inner city—all these are environmental problems, and are receiving increasing attention from environmental groups. Environmental pollution is highly discriminatory. The black man in the ghetto and the working man in the factory suffer more acutely for the simple reason that they cannot escape…What is a more general, long-term problem for the rich is an immediate threat to life and health for the poor. Anyone tempted to view ecology as a purely middle-class issue should take a hard look at the following facts.

The rest of the article lays out studies and reports on pesticides, “A comprehensive study by Dr. Emil Mrak for the Dept. of HEW found that black people had almost twice as much DDT in their fat tissues as did white people.” It also highlighted lead poisoning, occupational health hazards, mass transit, solid waste, water pollution, overpopulation, and air pollution, “One out of four patients in the Harlem hospital now suffer from asthma, compared with 5% in 1952.” Edey concludes:

In the past, conservationists have not paid nearly enough attention to these urban environmental problems, but there has been a dramatic change in the last few years. New environmental groups are concerned and active in all the above issues… Do not ask us to make a false choice between a livable city and a livable environment. These are not different problems, but part of the same problem.

Anchoring an environmental critique in poverty and unequal distribution of ecological consequences directly leads to the environmental justice movement emerging a decade later. Contributing even more to the foundation of this movement were the murderous affects of countless acts of industrial disposal that could no longer be hidden as the 1970s unfolded. In 1978, the residents of Love Canal in Niagara Falls, NY, were discovered to be living over a 1940s-era chemical dump. Investigations showed that one-third of the residents had suffered chromosomal damage, and after similar toxic waste disasters emerged elsewhere, the US Congress enacted the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA), better known as the “Superfund,” which is the law that requires polluters to clean up their own pollution. Love Canal residents, and soon after those of Times Beach, Missouri, argued that their working-class communities were living on toxic waste dumps precisely because they lacked the political and economic power to stop it.

Toxic waste sites were soon discovered all over the country, including San Francisco, where radiological and toxic waste still dominates the former Naval Shipyard at Hunter’s Point. Several dozen other sites have been added to the California Superfund list too, many in the predominantly African-American neighborhood in the southeastern part of the City. Just beyond the southern border of San Francisco lie at least five federal Superfund sites in the neighboring jurisdictions of Daly City and Brisbane.(31)

A decade into the 21st century we are still far from having altered the underlying logic of our culture. There are successes to be sure, and countless millions of people have a more profound understanding of our interdependent existence on Earth than those alive in the mid-20th century did. Modern ecological thinking is characterized by an integrative and broadly systemic way of framing planetary life, stretching from the global awareness of climate change down to the local focuses of countless community-based organizations and an abiding awareness of both biological and social interdependence. That’s all to the good. But the hundreds of ecology initiatives and organizations, with their tens of thousands of activists and volunteers, are still fighting a Sisyphean struggle, taking small steps only to be overrun by naked economic power unchecked by ecological sanity again and again. As quoted at the outset of this essay, Brower warned a half century ago that environmental victories are always temporary, and that hasn’t changed much. The evolution of the ecology movement is only starting to come into focus, and this article is at best a tiny contribution to a larger history that we have to learn. A half century hasn’t yet gotten us to the tipping point towards a radically redesigned way of life. But the efforts forged in the heat of the anti-war and anti-nuclear movements back then remain an indispensable foundation for our contemporary efforts to harmonize human life with Earth’s natural systems.

Notes

1. In the 1930s, a group of women organized the Marin Garden Club and raised enough money to hire the first county planner in the state because the Golden Gate Bridge was being built and “we don’t want to be like Los Angeles!” Bill Evers, founder Planning & Conservation League, interview with author, November 2009.

2. BCDC was created by the 1965 McAteer-Petris Act and strengthened after a few years by the state legislature. Author interviews conducted for this article between October 2009 and January 2010 with Sylvia McLaughlin, Doris Sloan, Jerry Mander, Alvin Duskin, Larry Orman, Sam Schuchat, Ruth Gravanis, Peter Berg, Judy Goldhaft, Monica Moore, Tom Turner, Saul Bloom, Karen Pickett, John Knox, Bill Evers, Harold Gilliam, Carole Schemmerling, Julia May, Miya Yoshitani, Juliet Ellis, Jason Mark, Antonio Roman-Alcala, and Kirsten Schwind.

3. Warren J. Belasco, Appetite for Change: How the Counterculture Took on the Food Industry 1966-1988 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989) 23.

4. Evers, interview.

5. Douglas Bevington, The Rebirth of Environmentalism: Grassroots Activism from the Spotted Owl to the Polar Bear (Island Press: 2009).

6. Ibid., 241.

7. Saul Alinsky’s influence goes back to his original Reveille for Radicals, 1946.

8. Robert Gordon, “Poisons in the Fields: The United Farm Workers, Pesticides, and Environmental Politics,” The Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 1 (February 1999): 51, 59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3641869?origin=JSTOR-pdf (accessed February 2, 2010).

9. By 1999 in Seattle for the WTO protests, it could be treated as remarkable and unprecedented to have an alliance of “Teamsters and Turtles,” but a closer reading of history shows that just such an alliance helped produce a good deal of the legal foundation for environmental protection and workplace safety in the early 1970s.

10. I moved to San Francisco on January 1, 1978 to work for Citizens for a Better Environment (CBE, now Communities for a Better Environment). We were hired to canvas for the new California office, CBE having just migrated from Chicago and Milwaukee where they’d established themselves as a grassroots environmentalist group focused on air and water pollution around Lake Michigan. I spent the first six months of 1978 knocking on doors in every neighborhood around the greater Bay Area, getting a crash course in the issues of the day (toxic pesticides and herbicides, acid rain, sewage and waste management, and much more). It was a bit difficult to “sell” the organization door-to-door as no one had ever heard of them and during those first months they had not yet managed to file any lawsuits or achieve any policy changes through their interventions. Nevertheless, we entered the fray, crossing paths with canvassers from Greenpeace and Citizens Action League, hoping to be the first to hit a given neighborhood before they were saturated with earnest requests for money.

11. Bloom had previously canvassed for the Citizens Action League, another organization firmly rooted in the community organizing philosophy of radical reformer Alinsky.

12. See Alejandro Murguia’s essay “Poetry and Solidarity in the Mission” in this volume for more on the San Francisco–Sandinista connection.

13. Belasco, Appetite for Change, 16.

14. In the 1980s, Orman helped bring Alice Waters, Baywolf, Green’s, and local producers together, in what soon exploded into the many strands of a broad new food movement with much of its initial creative impetus emerging in the Bay Area.

15. See Pam Peirce’s essay “A Personal History of the People’s Food System” in this volume for a completely different story about food stores in the 1970s.

16. See Matthew Roth’s essay “Coming Together: The Communal Option” in this volume.

17. Barbara Epstein, Political Protest & Cultural Revolution: Nonviolent Direct Action in the 1970s and 1980s (University of California: 1991) 51.

18. The Sierra Club’s internal dispute over Diablo Canyon was one reason for the ouster of David Brower.

19. Duskin was a successful women’s fashion designer with his own factory in San Francisco at 3rd and Bryant in the mid-1960s when he got involved with Jerry Mander and became the public figure who undid the sale of Alcatraz to Texas oilman Lamar Hunt. Duskin credits Alinsky’s influence for some of his success in those early organizing campaigns. They were neighbors in 1961.

20. Alvin Duskin, interview with author, January 12, 2010, San Francisco, CA.

21. The Clamshell Alliance united hundreds of affinity groups around New England in a campaign of nonviolent direct action to stop the building of the Seabrook nuclear power plant on coastal New Hampshire. Their April 1977 attempt to occupy the construction site led to 1,414 arrests, and a movie, The Last Resort that was shown around the country to spread the model. I was involved in screening the film in late 1977 in Santa Rosa, California, as a benefit for a fledgling group we started called Sonoma County Citizens for Understanding Energy. It raised about $82 which we banked, and within the following year, I’d moved to San Francisco and someone else had taken that money and started a chapter of the Abalone Alliance called SonomorAtomics—a much better name!

22. San Francisco Good Times 2, no. 43 (October 30, 1969): 6-7.

23. In 1967, Cliff Humphrey, a former archaeology student at University of California, Berkeley founded Ecology Action and set up the country’s first drop-off recycling center.

24. The City Office of Recycling had been formed in 1979 to plan, coordinate and expand the various activities attempting to reduce the City’s waste stream. Activists from the nonprofit recyclers were involved in the effort to create this new city program. San Francisco Community Recyclers was founded in 1980 in response to two important points in the city’s recycling development. First was the growth and maturation of the non-profit community based recycling centers. The second was the emergence of the city recycling program.

25. A renewed and expanded Open Space Fund was passed by a 3-to-1 margin in March 2000, proving again how much San Franciscans appreciate their open space and parklands.

26. Ray Dasmann was the author of The Destruction of California (New York: MacMillan, 1965), an important early environmental analysis of statewide ecological destruction.

27. See Jana Blankenship’s essay “The Farm by the Freeway” in this volume.

28. As it still does today in 2010, when like Frankenstein, it is being proposed AGAIN.

29. Peter Berg, Beryl Magilvy, and Seth Zuckerman, A Green City Program for San Francisco Bay Area Cities & Towns (Planet Drum Books: 1989).

30. A decade later, Friends of the Earth split too, with Brower pushing for a more decentralized organization against those who favored an “inside the Beltway” (DC-focused) lobbying approach. Brower and others then put their energies into the Earth Island Institute, an umbrella organization that provides incubator space and a home to dozens of local, grassroots organizations.

31. Locally, ARC/Ecology, GreenAction, Literacy for Environmental Justice, and Communities for a Better Environment all campaign against the toxic environment of southeast San Francisco. In Richmond near the massive Chevron refinery, the West County Toxics Coalition organizes political opposition to the multinational’s continuing poisoning of the local air, water, and soil, along with the Asia/Pacific Environmental Network’s work with the Laotian refugee community there, and Communities for a Better Environment. Parallel efforts exist in Silicon Valley in the South Bay.

reprinted from the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.

Find the book at City Lights!

Find the book at City Lights!

The research for this article was based in part on a series of oral history interviews done as part of the "Ecology Emerges" series.