Marty MacIntyre and the Lake Street Bike Lanes

Historical Essay

by Andy Thornley

You probably ride on Lake Street’s bike lanes now and then, and you may know that they’re the first bike lanes ever striped in San Francisco. But you may not have heard the story of how those lovely lanes came to be back in 1971, how an ordinary neighbor rolled up his sleeves, got some clipboards, printed some flyers, and organized his neighbors to tame Lake Street.

Martin MacIntyre is the fellow to thank for getting bike lanes rolling in the Richmond District. He still lives nearby, on the shoulder of Lone Mountain, and he just celebrated his 80th birthday. In all these years Marty’s never ridden a bike on Lake Street (it’s true!), he just loves healthy civilized neighborhood streets, and he’s still working with neighbors to shape them.

Marty MacIntyre at the 1971 opening of the Lake Street bike lane.

Photo: courtesy Andy Thornley

Pedal back for a moment to San Francisco in autumn 1970. Joe Alioto was mayor, Ronald Reagan was governor, and Richard Nixon was president. The 1960’s had nurtured a growing awareness of the environment and community, intertwined into struggles to combat pollution and freeway expansion and “blight clearing” urban renewal. 1970 brought the first Earth Day and creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency, NEPA and CEQA, among other initiatives.

The corrosive effect of automobility on neighborhoods was starting to be understood by 1970; European cities saw growing grassroots movements for traffic calming, as in the Dutch city of Delft where angry residents fought cut-through traffic by turning their streets into “woonerven,” or “living yards.” Other cities began to reclaim streets from cars and prioritize people getting around on foot and on bicycles.

In 1970, 33-year-old Martin MacIntyre signed a lease on a house on Lake Street between 12th Avenue and Funston Avenue. A US Public Health Service dentist, Marty had been transferred from Buffalo NY to the Public Health Service Hospital located just inside the Presidio at 15th Avenue (the old PHSH closed in 1988 but it’s still standing, converted to the Presidio Landmark apartments in 2010).

Marty’s commute to the hospital was a walk of just a few blocks, but he soon grew annoyed and alarmed at the traffic-tormented condition of Lake Street. Drivers zoomed along heedlessly on too-wide lanes (rush hour commute traffic was especially perilous) and there were no STOP signs between Arguello Boulevard and 25th Avenue, save for a traffic light at Park Presidio. Marty and his wife Rosemary thought it was inexcusable that their six-year-old daughter couldn’t safely cross the street to get to Mountain Lake playground, and started asking neighbors whether anything could be done about this problem.

And so the Lake Street Traffic Safety Committee was formed in early December 1970, “to improve safety for pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists along Lake Street and adjoining avenues.” Marty got to work on a campaign plan, and quickly fielded a small cadre of volunteers brandishing petitions and writing letters. The committee power-mapped the people who needed to say Yes to fix the street, from the mayor to the board of supervisors, city agency heads to business groups, the AAA and SPUR and churches and schools. Their key target was Public Works Director S. Myron Tatarian, in charge of traffic engineering and streets generally (the SFMTA wouldn’t be created till 1999).

During the first two weeks of December, a swarm of three dozen volunteers gathered over 700 petition signatures, and on December 15, 1970, the Committee sent the petitions with a letter to Myron Tatarian, laying out the case to tame Lake Street and summoning him and various officials to a community meeting one month hence. Copies of the letter were sent to identified VIPs and influencers.

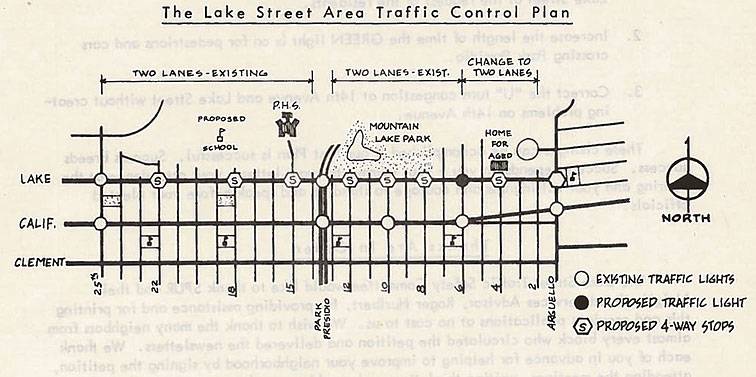

The Lake Street Committee organized and hosted a public meeting at Sutro Elementary School on January 28. City traffic engineer Norman Bray presented his team’s traffic study and some initial recommendations to the community. “Those present at the meeting authorized the Committee and others who volunteered to consult with the City traffic engineer and develop a traffic-control plan which would be acceptable to the community,” the Committee’s newsletter reported. “After several meetings, a Plan was accepted by the Committee and it will be presented at a hearing of the Board of Supervisors Committee on Fire, Safety and Police on March 11.”

The 1971 Lake Street plan

On Thursday March 11, the Board of Supervisors’ Committee on Fire, Safety and Police (Terry A. Francois, Chairman) held a hearing on the Lake Street Traffic Safety question, and the following Monday (March 15, 1971) the full Board of Supervisors approved installation of STOP signs on Lake at 4th, 6th, 9th, 12th, 15th, 19th, and 22nd Avenues.

Victory! But what about the bike lanes?

The Committee didn’t win a traffic signal at 6th Avenue (still none there), but they did keep talking with Myron Tatarian and Norman Bray and others. Marty connected with Ed McDevitt, Director of Recreation for the Department of Recreation and Parks and a member of the brand-new SF Bicycle Coalition, who was working to establish a network of designated bicycle routes in the City. Bike lanes were quite novel in the US; the nation’s first bike lane had been created in Davis, CA, in July 1967 and state law had been signed by Governor Reagan establishing the right for California cities to install bike lanes.

In early May, the Lake Street Committee wrote to the neighbors:

Five months ago we began a project that many of us thought would be a waste of time. After all, many of us had tried before to get stop signs to no avail. Well, one more time. Maybe this time something will be done. A petition, a flyer, a public meeting, another flyer, still another flyer, a hearing at the Board of Supervisors and EUREKA!!! They passed it!!! That was March 15th. “Where are those signs? Probably a hitch somewhere.”

There was a hitch. Your Lake Street Traffic Safety Committee had decided to ask for separate bicycle lanes. “What bicycle lanes? -- you got to be out of your minds. They’ll never do that!!!”

You want to bet? The Department of Public Works has just approved bicycle lanes for Lake Street. “I won’t believe it until I see it. When will this all happen?” . . .

The Lake Street Committee sent out a press release in late May: “A neighborhood’s victory of man over machine will be celebrated with a noontime parade this Sunday on Lake Street in the Richmond District. San Francisco’s first traffic lane reserved exclusively for bicycles will be dedicated, and seven new stop signs designed to slow traffic on that street will be unveiled.”

Lake Street celebration parade 1971.

On Sunday May 23, 1971, the neighborhood gathered for a great celebration of the newly-tamed Lake Street. Marty had secured a parade permit for the day, and planned out a great celebration:

INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE PARADE PARTICIPANTS

- 1. Make lots of NOISE.

- 2. Do not litter.

- 3. Take pictures and make tape recordings--this is history and you are here.

- 4. Do not touch cars no matter what you think of them.

- 5. Carry a sign with an appropriate slogan--Who knows, you may get on TV.

- 6. Put a name tag on anyone you think may not be able to find his or her way home.

- 1. Make lots of NOISE.

VIPs mixed with little kids and locals. At noon the new bike lanes were inaugurated, with ribbons cut by Jack Murphy of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, Superintendent of Recreation Ed McDevitt, and State Senators Peter H. Behr and Milton Marks, Jr. A bike race from 3rd Avenue to 4th Avenue served to break the final ribbon on the bike lanes.

Next, the new STOP sign at 4th Avenue was unveiled, with Supervisor Dianne Feinstein sharing honors with SPUR’s Roger Hurlbert, DPW traffic engineer Norman Bray, and Lake Street Committee member Douglas Cornell, Jr. The parade got underway with cheers and sousaphone blasts and made its way toward 25th Avenue, stopping every few blocks to unveil new STOP signs. The best signature-gatherers were given the honor of revealing the signs together with VIPs including Supervisors Terry Francois, Robert Mendelsohn, and Ronald Pelosi (Nancy Pelosi’s brother-in-law).

By 1:00 the parade had arrived at 22nd Avenue where the last set of STOPS was unveiled, after which the merry band of traffic calmers retired to Golden Gate Park for a picnic in a meadow near the Pioneer Mother statue.

The new bike lanes were complemented with painted islands at some intersections, along with all the new STOP signs. One grumpy motorist wrote to the SF Examiner later that summer: “Lake Street has become a paint manufacturer’s dream and a street painter’s joy . . . what has happened, of course, is that one can no longer drive with any sanity along this pleasant, wide street from Arguello to 28th Avenue . . . and the silliest part is that while EVERY do-gooder loves the bicyclists, I have yet to see one using the lanes reserved exclusively for them. What a waste of good space!”

A few months later (Sept 1971) the city measured traffic and speeds on Lake Street, and found that vehicular traffic had been reduced by 30% and average speed cut from 35 miles per hour to 25 miles per hour.

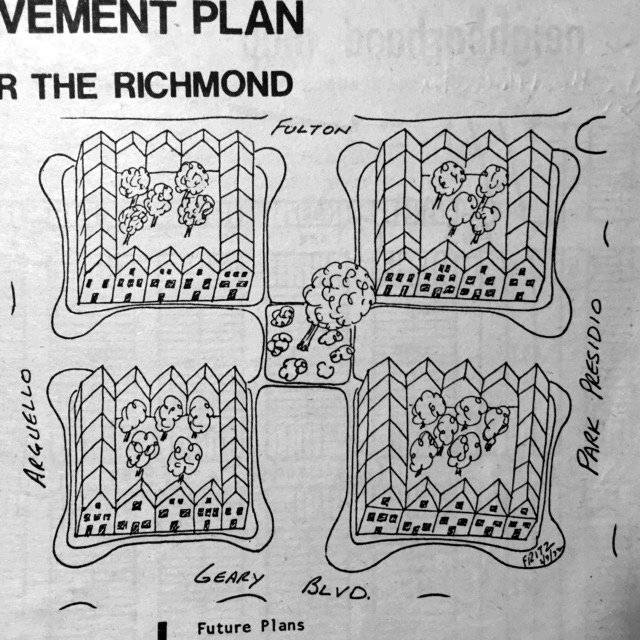

Even before the Lake Street bike lanes had been installed, the momentum of the Lake Street Committee had led to formation of the Planning Association for the Richmond (PAR), one of the city’s oldest neighborhood groups. And PAR and Marty and SPUR and partners began moving forward with an ambitious plan to civilize the streets of the Inner Richmond and establish “parks in the streets” (as we now admire in Barcelona). And Marty took up the charge for district elections for the Board of Supervisors, and other civic adventures . . .

Marty MacIntyre recounts the story of 1973’s Prop K campaign at an SFBC Survey Ride in June 2016

But those stories will have to wait for another time – for now let’s just say Happy Birthday, Marty, and thanks for the bike lanes!