Chinatown Life at Turn of 20th Century

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

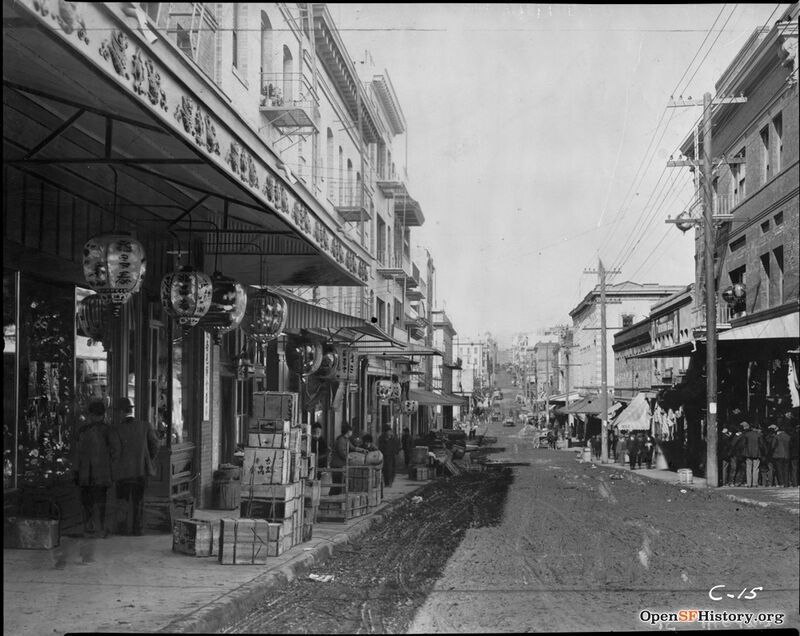

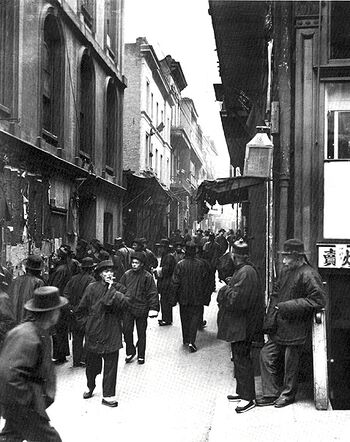

Grant Street near Washington, c. 1910.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.1228

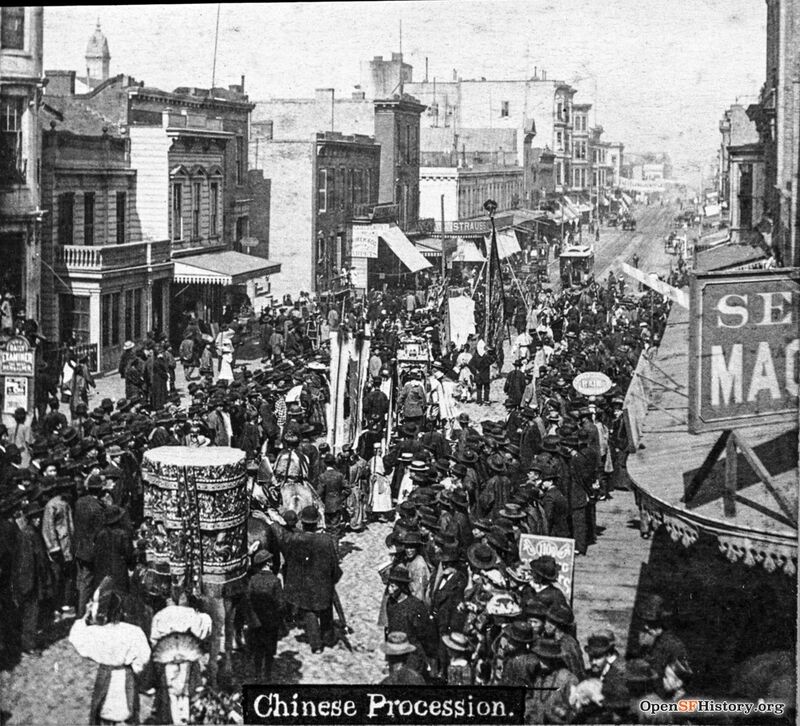

The intersection of California and Mason streets lies at the crest of Nob Hill, location of the Flood and Hopkins mansions and of the Fairmont Hotel (the foundation of which James Fair intended, until his death, as the base of the grandest Nob Hill house of them all). Three blocks down California Street toward the bay is Grant Avenue (Dupont Street until 1908), center of the densely populated Chinese quarter that in the late nineteenth century took in the blocks from California to Broadway, between Kearny and Stockton streets. To white San Franciscans, Chinatown seemed sometimes bizarre, sometimes revolting, but always exotic. It was a city within a city, with its own social and economic systems, virtually autonomous with its own forms of government exercised through clan and district associations and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the “Six Companies.” The physical appearance of Chinatown today, without the neon signs and some of the pseudo-Chinese architectural flourishes, is probably very close to what it was in the late nineteenth century.(32)

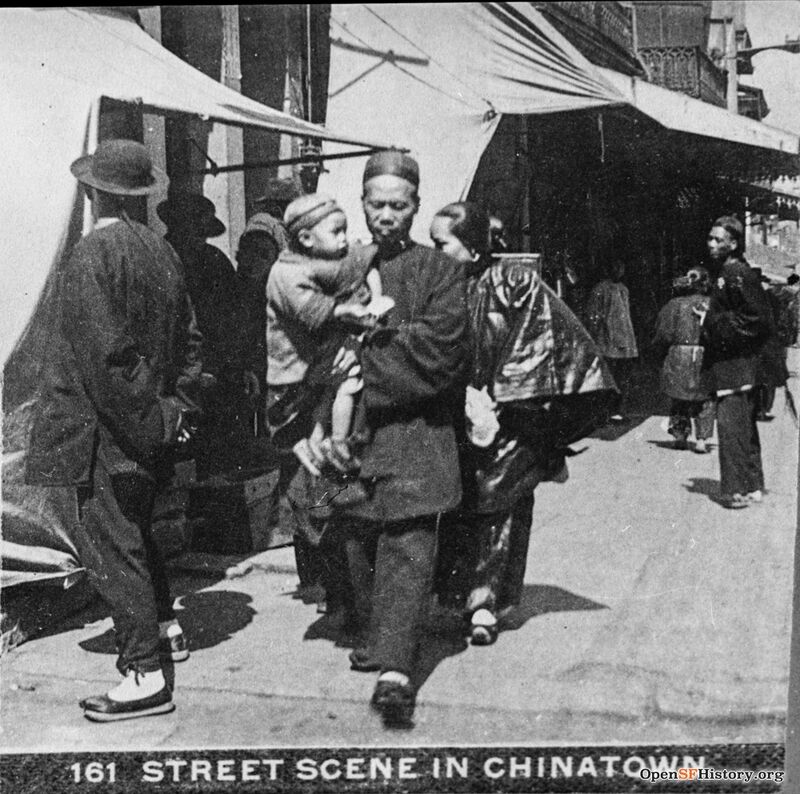

Chinatown street scene, 1880s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.00579

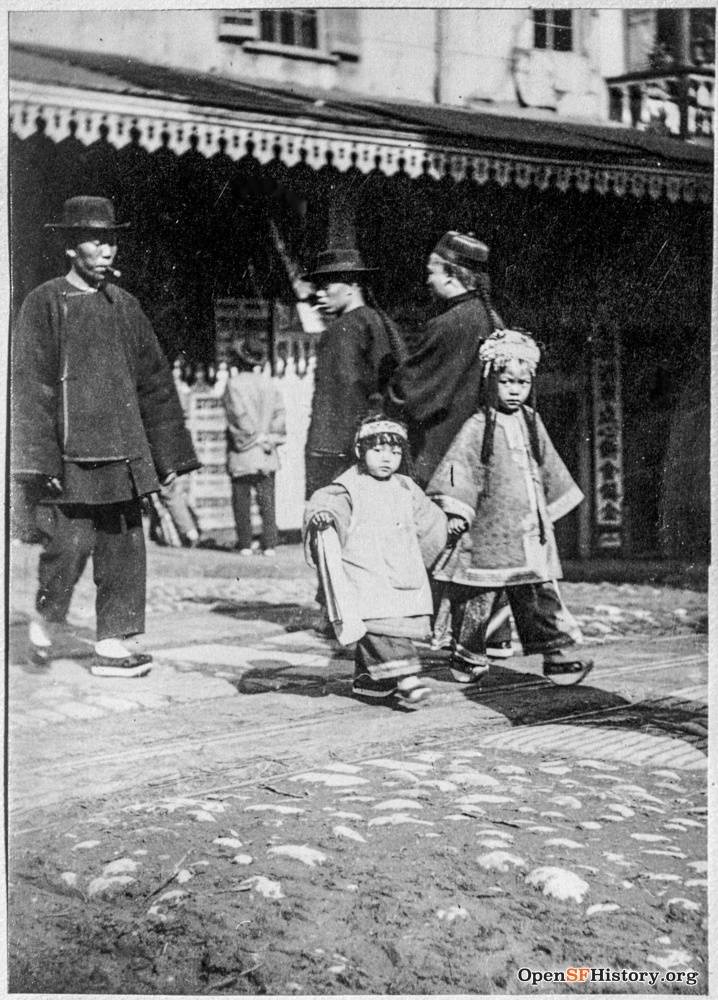

Architectural historian Randolph Delehanty notes: “When the district burned down completely in 1906 it was almost immediately rebuilt (most of it with salvaged bricks) to be much like the downtown Civil War city.” Although the buildings looked much like those in the rest of the city, the banners, signs, and other aspects of Dupont Street made it distinctly Chinese. One visitor in the 1870s described the scene: “The Chinamen were clothed in plainly-cut blue tunics, had straw or cloth covering their heads, and shoes on their feet resembling slippers down at the heels. The shops were adorned with pendant flags bearing inscriptions in Chinese. The entire street was filled with these strangely decorated and strangely arranged shops.” Arnold Genthe, a German-born photographer who has left the largest collection of pictures of the area, described Chinatown at the turn of the century: “The painted balconies were hung with windbells and flowered lanterns. Brocades and embroideries, bronzes and porcelains, carvings of jade and ivory, of coral and rose crystal, decorated the shop-windows. The wall spaces between were bright with scarlet bulletins and gilt signs inscribed in the picturesque Chinese characters.’’ Buildings covered every part of each block. Narrow alleys, wide enough for several people abreast, but too nar¬row for vehicular traffic, ran every which way through the centers of blocks, connecting buildings in the center to the larger streets.(33)

Clay & Grant 1890s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.04128

Throughout its existence, Chinatown has been densely crowded. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, men from the same village with the same name frequently shared a room:

In 1913, all the cousins from the Liu family in my village had one big room so all the members could fit in it, and we slept in that room, cooked in that room, one room. Anybody who had a job had to sleep outside the room, because he could afford space and get a bed for himself. Anybody who couldn’t find work slept in the beds in this room. At the end of the year, all the members would get together and figure out all the expenses.

At times in such rooms, beds were attached to the walls like shelves and used in shifts.(34)

In 1890, the Chinese population of San Francisco was 90 percent male. As late as 1920, the figure was 78 percent. This imbalance between the sexes helped to create a thriving vice traffic in Chinatown, just as a similar imbalance along the waterfront created a similar traffic there. In 1885, a special committee appointed by the Board of Supervisors contributed to prevailing anti-Chinese sentiments by locating 567 Chinese prostitutes, 104 houses of prostitution, 26 opium “resorts,” and 109 “barricaded gambling dens,” all within the six square blocks of Chinatown. During the 1920s, the San Francisco Police Department’s Chinatown Squad made a determined effort, largely successful, to eradicate vice activities, although many gambling establishments survived.(35)

Three occupations accounted for 36 percent of all Chinese workers in 1870: laundry workers, 64 percent of whom were Chinese; textile mill operatives, 64 percent Chinese; and cigar and tobacco industry workers, 93 percent Chinese. Chinese were also disproportionately represented among boot- and shoemakers, tailors, fishermen, hucksters and peddlers, laborers (25 percent), and servants (18 percent). During the 1870s and early 1880s, many Chinese worked truck gardens in parts of the Western Addition, others fished on the bay, and still others were door-to-door peddlers, selling vegetables grown and fish caught by their countrymen. Truck farming and fishing later became Italian occupations, but the Chinese peddler was long a familiar sight, delighting children of the Mission District and the Western Addition with his visits.

Chung Ling was fruit and fish man. He carried the combined stock, suspended in two huge wicker baskets balanced upon a long pole, across his shoulders. . . . The uncertainty of the contents of the baskets—today only apples and cauliflower; tomorrow, cherries and corn; today, shiny silver smells; tomorrow, red shrimps with beards and black-beaded eyes—made a delight of his coining.

Another memoir noted that “if there was a Chinese holiday, tucked with the vegetables [would be] little bags of Chinese candy and nuts, gifts to us children.” In 1870, there were some 1,100 miners resident in San Francisco, 31 percent of whom were Chinese. Since the city had no mining operations, most of these were probably unemployed miners who had left the Sierra for the city, possibly driven from the mineral areas.(36)

Asians, most of whom were Chinese, constituted 7 percent of the city’s workforce in 1900. Laundry workers were still predominantly Asian (52 percent), as were cigarmakers (68 percent): garment workers were 31 percent Asian. However, Italians were replacing the Chinese as hucksters and peddlers. Italians made up 28 percent of that occupation and the Chinese only 15 percent. The same pattern appears in fishing, where the Chinese had outnumbered the Italians in 1870. By 1900, Italians accounted for 51 percent of fishermen. Chinese for only 13 percent. The proportion of Chinese among servants and waiters held stable, but the proportion of Chinese laborers declined markedly, from 25 percent in 1870 to 5 percent in 1900.(37)

Manufacturing industries with many Chinese workers showed lower wages than other manufacturing occupations. The average men's clothing worker earned $319 per year in 1900, and the average cigar worker made only $358, both well below the citywide average of $525. One factory owner in 1876 acknowledged that “to Chinamen, on an average we pay less. ... If the Chinamen were taken from us, we should close up tomorrow.” One woolen goods factory in 1880 employed both Chinese and white labor for some tasks. Carders prepared wool for spinning by brushing it to disentangle the fibers; a Chinese carder was paid $1.00 per day in 1880 (down from $1.08 for 1870–1879), but a white boy made $1.75 for the same work. Between 1870 and 1880, the wages of white carders fluctuated considerably, between $1.25 and $2.00, but the general trend was upward. The wage paid Chinese carders was stable until 1880 when it was cut by eight cents per day. Similarly, white weavers made $1.25 per day throughout the period 1870–1880, but Chinese weavers made only $1.08 from 1870 to 1879, and $1.00 in 1880. Chinese laborers earned $1.00 per day, and there were no white laborers. The only other employees paid only $1.00 per day were white women. White laborers in a furniture factory, by contrast, earned $2.00 per day, and in some years $2.50. In a boot and shoe factory employing white labor, the wages varied from $2.50 to $3.00 per day, but in a woolen mill, wages for Chinese workers varied from only $1.00 to $1.20 in 1880.(38)

Procession on Stockton near Jackson, c. 1885.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.01162

Ross Alley from Jackson Street, c. 1898

Photo: Arnold Genthe

Most Chinese worked in or near Chinatown. The 1885 supervisors’ committee found 427 sites for cigar making, 599 for boot and shoe making, 974 for clothing manufacturing, 255 for underwear, and 71 other work rooms, with a total of 2,326 employees and 1,245 sewing machines. Such work rooms were to be found everywhere, from the third and fourth stories to “cellars which are certainly dark, and probably unhealthy” (the observation of an English visitor around 1870). Other Chinese worked outside Chinatown—as fishermen, launderers (Chinese laundries existed throughout much of the city, places of both work and residence), and as servants in the Western Addition and on Nob Hill and Pacific Heights. Travel outside Chinatown, however, was potentially dangerous.

I myself rarely left Chinatown, only when I had to buy American things downtown. The area around Union Square was a dangerous place for us, you see, especially at nighttime before the quake. Chinese were often attacked by thugs there and all of us had to have a police whistle with us at all times. . . . once we were inside Chinatown, the thugs didn’t bother us.(39)

Chinatown was a segregated area, as thoroughly segregated as black districts of the South during the same time period. Chinese could not become citizens through naturalization, could not present testimony in court, could not marry a white person, could not live outside Chinatown except in laundries or as domestic servants, and had been driven from many occupations. There was a school in Chinatown, and Chinese children were not allowed to attend any other public school until the period just before World War I. Discrimination became especially intense during the last quarter of the nineteenth century not only in San Francisco but also throughout the West. One immediate consequence was that Chinese from small towns throughout the West flocked to the relative safety of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Another consequence was that many returned to China. Between 1890 and 1900, the Chinese population of San Francisco dropped by about half, and it continued to decline until 1920. Some remained in the Bay Area, as fishermen in small villages outside San Francisco, but the Chinese population of the entire state fell by at least a third during that decade.(40)

Notes

32. For one example of the reaction of white San Franciscans to Chinatown, see Atherton, My San Francisco, pp. 53–56, where she recounts a visit to a Chinatown restaurant and theater in the 1880s, complete with encounters with an opium smoker and a group of prostitutes. Ivan Light, “From Vice District to Tourist Attraction: The Moral Career of American Chinatowns, 1880–1940,” Pacific Historical Review 43 (Aug. 1974):367–394; Stanford M. Lyman, “Conflict and the Web of Group Affiliation in San Francisco’s Chinatown, 1850–1910,” Pacific Historical Review 43 (Nov. 1974):473–499; Victor G. Nee and Brett de Bary Nee, Longtime Californ': A Documentary Study of an American Chinatown (Boston, 1974), pp. 65–69, 272–277; William Hoy, The Chinese Six Companies: A Short General Historical Resume of the Origin, Function, and Importance in the Life of the California Chinese (San Francisco, 1942).

33. Delehanty, Walks and Tours, pp. 197–198; W. F. Rae, Westward by Rail (London, 1871), quoted in Oscar Lewis, ed., This Was San Francisco: Being First-Hand Accounts of the Evolution of One of America's Cities (New York, 1962), pp. 172–173; Arnold Genthe, As I Remember (New York, 1936), quoted in Laverne Mau Dicker, The Chinese in San Francisco: A Pictorial History (New York, 1979), p. 16; a map of streets and walkways may be found following p. 214, in San Francisco, Board of Supervisors, Municipal Reports (San Francisco, 1884–1885). See also Helen Virginia Gather, The History of San Francisco's Chinatown (San Francisco, 1974).

34. Wei Bat Liu, quoted in Nee and Nee, Longtime Californ’, pp. 64–65.

35. Table 14, “The Chinese Population by Counties: 1890, 1880, 1870,” and Table 20, “Population as Native- and Foreign-Born and White and Colored, Classified by Sex,” U.S. Census Office, Department of the Interior, Compendium of the Eleventh Census: 1890, 3 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1892), 1:516, 668–669; “Supplemental Tables for Indian, Chinese, and Japanese Population,” U.S. Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce, Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920, 11 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1922–1923), 3:128. Each house of prostitution, gambling establishment, and opium den is located and identified as Chinese or white as of 1885; see “Condition of the Chinese Quarter,” in San Francisco, Municipal Reports (1884–1885), pp. 160–214, esp. the map following p. 214, which locates sixty-six houses of prostitution for Chinese and thirty-eight for whites; Dicker, Chinese in San Francisco, pp. 23–24; Mildred Crowl Martin, Chinatown's Angry Angel: The Story of Donaldina Cameron (Palo Alto, 1977), pp. 36–211; Flamm, Good Life in Hard Times, ch. 6.

36. Table 66, “Occupations: Fifty Cities,” U.S. Census Office, Department of the Interior, Compendium of the Ninth Census (Washington, D.C., 1872), pp. 618–619; Table 36, “Persons in Selected Occupations in Fifty Principal Cities,” U.S. Census Office, Department of the Interior, Tenth Census of the United States: 1880, 22 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1883), 1:902; Gather, The History of. . . Chinatown, pp. 33–39; Dicker, Chinese in San Francisco, pp. 3–6; Alexander Saxton, The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley, 1971), pp. 57–66. For descriptions of door-to-door peddlers, see Levy, 920 O'Farrell, pp. 196–198; Hedgpeth, My Early Days, p. 17; and Amelia Ransome Neville, The Fantastic City: Memoirs of the Social and Romantic Life of Old San Francisco (Boston, 1932). Levy also describes their Chinese laundryman (pp. 198–200), Hedgpeth describes both their laundryman and a door-to-door Chinese ragpicker (p. 18), and Neville tells of Chinese door-to-door peddlers selling silks and brocades, carved ivory and sandalwood, lacquer ware and tea.

37. Table 43, “Total Males and Females 10 Years of Age and over Engaged in Selected Groups of Occupations, Classified by General Nativity, Color, Conjugal Conditions, Months Unemployed, Age Periods, and Parentage, for Cities Having 50,000 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, 20:720–724; Elgie, “Development of San Francisco Manufacturing,” pp. 89–91.

38. Table 8, “Manufactures in Cities by Specified Industries: 1900,” Twelfth Census, vol. 8, pt. 2, 52–57; U.S. Census Office, Department of the Interior, Report on the Statistics of Wages in Manufacturing Industries (Washington, D.C., 1886), pp. 15, 41, 379; Nee and Nee, Longtime Californ’, p. 45.

39. Rae, Westward by Rail, quoted in Lewis, This Was San Francisco, p. 173; a survey of the 1900 Census Schedules for various neighborhoods will show the laundries and, for the Western Addition, Nob Hill, and Pacific Heights, the live-in servants; Gim Chang, quoted in Nee and Nee, Longtime Californ' , p. 72. For another account of the dangers posed to Chinese by “hoodlums” outside Chinatown, see Samuel Williams, “The City of the Golden Gate,” Scribner's Monthly 10 (July 1875):276. For a list of manufacturing done in Chinatown, see San Francisco, Municipal Reports (1884–1885), pp. 215–219.

40. For the decline in population, see the census sources cited in note 35; for school segregation, see Charles M. Wollenberg, All Deliberate Speed: Segregation and Exclusion in California Schools: 1855–1975 (Berkeley, 1976), pp. 31–44; Nee and Nee, Longtime Californ’, pp. 32–33, 61.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”