Beat Generation and San Francisco's Culture of Dissent

Historical Essay

by Nancy J. Peters, originally published as "The Beat Generation and San Francisco's Culture of Dissent" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998)

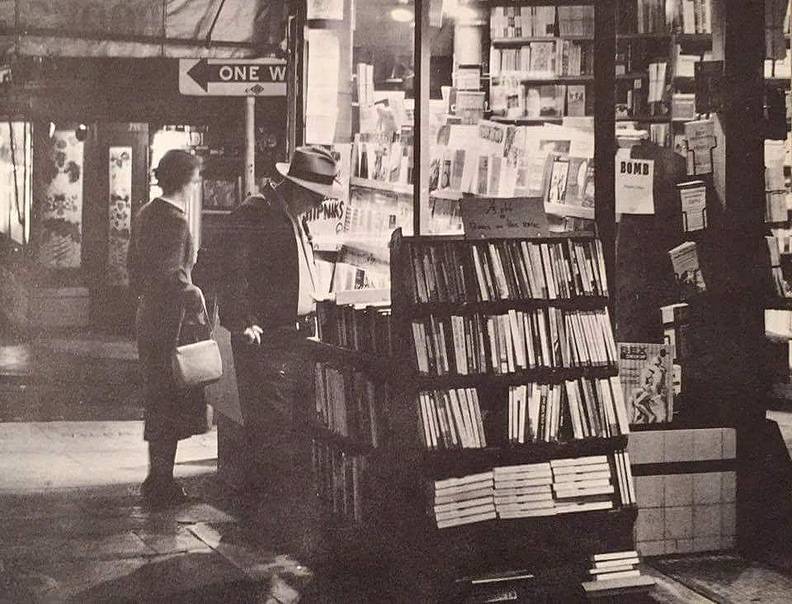

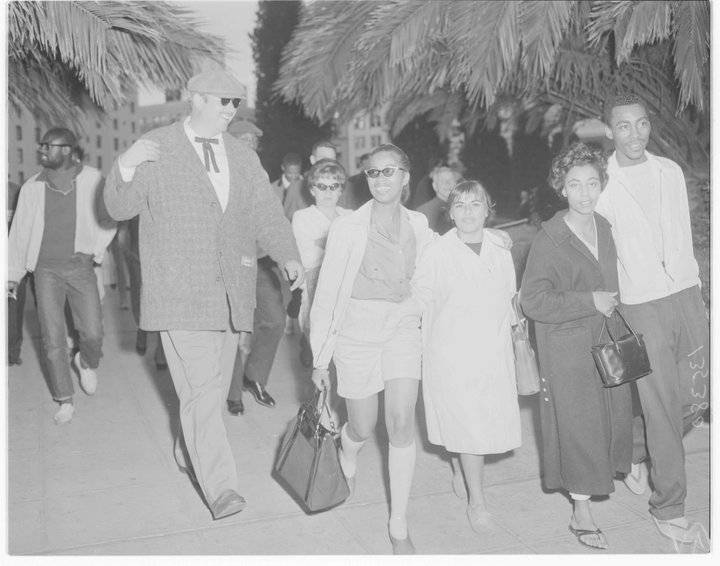

Browsing on Columbus outside City Lights, 1950s.

Photo: City Lights Books

More than two thousand people from diverse communities and generations gathered in April 1997 at a memorial service for Allen Ginsberg at San Francisco’s Temple Emanu-El. The presence of so many celebrants from the liberatory movements that followed in the wake of the Beat Generation demonstrated the strength and range of the city’s abiding culture of dissent. San Francisco has always been a breeding ground for bohemian countercultures; its cosmopolitan population, its tolerance of eccentricity, and its provincialism and distance from the centers of national culture and political power have long made it an ideal place for nonconformist writers, artists, and utopian dreamers. An outsider literary lineage originated with the Gold Rush satirists, continuing on through such mavericks as Frank Norris, John Muir, Ambrose Bierce, Jack London, and the San Francisco Renaissance writers of the 1940s. The beat phenomenon that took shape in San Francisco in the mid-fifties not only dislodged American poetry from the academic literary establishment, it invigorated a democratic popular culture that was to proliferate in many directions: the antiwar and ecology movements, the fight against censorship, the pursuit of gay, lesbian, minority, and women’s rights. Drawing on Whitman’s ecstatic populism, the prophetic radicalism of William Blake, and the performance heritage of oral literatures, the beats created a style of poetic intervention that inspired following generations to challenge oppressive political and cultural authority.

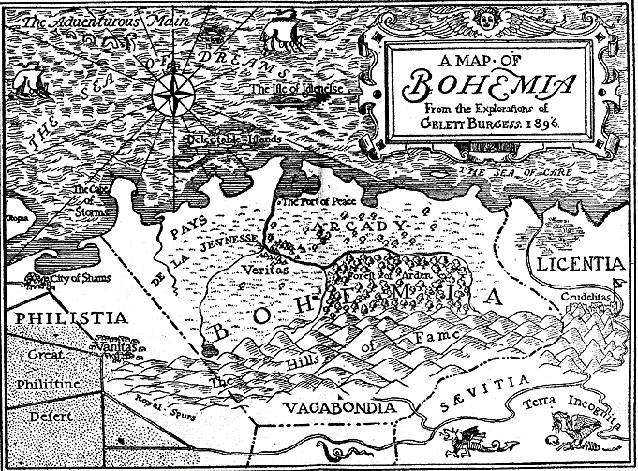

A map of "Bohemia" from 1896.

The idea of bohemia caught the imaginations of writers in early San Francisco with Henri Murger's Scénes de la Vie Bohéme (1844), which depicted life in the Latin Quarter of Paris, where artists had been renouncing their bourgeois origins since the revolution of 1830 to live for love and a more egalitarian society. It was thought that Bohemia was the country of origin of Gypsies, who were regarded as an ideal nomadic community that flourished outside the constraints of established society.

Murger's book enjoyed immediate popularity, and by the 1860s word of it had reached San Francisco writers. In those days San Francisco was a rapacious society that offered boundless opportunities for the savage exploitation of man and nature. There was certainly no literary canon; and literary expression took the form of exaggeration, hoaxes, and the kind of boisterous humor that reached its high point in Mark Twain's mining novel Roughing It. Many writers were manual laborers, shopkeepers, housewives, and transients; and the realistic narratives of pioneers and miners who survived the hazards of emigration and settlement were often so harrowing that they surpassed the wildest fiction.

The city's earliest literature, then, was both democratic and anarchic; at the same time, the lawlessness of the city seemed to elicit from some of its poets a nostalgia for classical literary forms and an imagined lost civility of remote times and places, so that a vaguely Apollonian standard of order and proportion coexisted anachronistically with violent and macabre stories and homespun accounts of daily life. Literary carpetbaggers from the East Coast occasionally tried their hand at taming the literary frontier, but most left town in defeat, proclaiming the city illiterate, chauvinistic, and pretentious. Although class society in San Francisco bore little resemblance to that of Paris, the city's writers were not blind to the obvious attractions of la vie bohéme, and they reveled the nights away in Montgomery Street bars and restaurants. The popular press was full of references to bohemians. Before he struck it rich with his sentimental gold-field fables, Bret Harte used the pseudonym "The Bohemian" and even wrote a column of whimsical vignettes in The Golden Era called "The Bohemian Feuilleton". Although women intellectuals and writers such as poet and actress Ada Isaacs Mencken and journalist Ada Clare, who had been friends of Walt Whitman, found San Francisco appallingly provincial, they welcomed the sexual and social freedom the frontier town's literary scene offered.

Bret Harte

Photo: courtesy Stephen Mexal

Another, later, bohemian community developed in the 1880s and 1890s around the intersections of Pacific, Washington, Jackson, and Montgomery Streets, where food was cheap and low-rent artist's studios were abundant. When the Montgomery Block building (at Montgomery and Columbus), which in the 1850s had been the center of business, banking, and mining speculation, emptied out as the commercial center moved south, artists and writers moved in. Over the years, more than 2,000 of them are reputed to have had spaces there, making the loss of this historic building in 1959 a black episode in the city's cultural history. (The Transamerica Corporation Pyramid now occupies the site.) Some of the notable writers and artists who lived in the Monkey Block were Ambrose Bierce, Joaquin Miller, George Sterling, Jack London, Sadakichi Hartman, Frank Norris, Yone Noguchi, Margaret Anderson, and Kenneth Rexroth. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera lived there while Rivera was painting the allegory of California's riches on the ceiling of the California Stock Exchange (now a tiny private luncheon club).

Montgomery Block, 1930s

Photo: Courtesy of Jimmie Schein

Doorway in the Montgomery Block, c. 1955.

Photo: © Shein & Shein

When the Montgomery Block studio space was taken over by business offices following the earthquake and fire of 1906, the writing community dispersed. The city’s unofficial poet laureate, George Sterling, moved to Carmel, where between 1906 and 1912 he and a small group of writers and artists attempted to create an alternative community that would use art as the basis for an ideal society. Hardworking writers, idealistic social reformers, muckrakers, and various classes of bohemian artists made up the population of the colony. Sterling and his friend Jack London, both ardent socialists, brought a political orientation to the group; Jimmy Hopper and Fred Bechdolt collaborated on a novel, 9009, that exposed prison conditions; and Upton Sinclair, who had come West after Hellicon Hall, his utopian colony in New York, had ceased to be viable, worked on plays and new social reform plans. One of the most gifted members of the group was Mary Austin, who was a feminist and early champion of Native American languages and cultures. Other residents and visitors to the community were writers Ambrose Bierce and Sinclair Lewis, photographer Arnold Genthe, poet Nora May French, painters Xavier Martínez and Ernest Peixotto, and muckrakers Lincoln Steffens and Ray Stannard Baker.

“There are two elements, at least, that are essential to Bohemianism,” Sterling once wrote in a letter to Jack London. “The first is devotion or addiction to one of the Seven Arts; the other is poverty. . . . I like to think of my Bohemians as young, as radical as their outlook on art and life, as unconventional. . . .” (Walker 1966) About as far as you can go from poverty, art, and radicalism is San Francisco’s Bohemian Club, of which both Sterling and Jack London, ironically, were once members. Organized in 1872 as a drinking club for male journalists, the Bohemian Club’s membership soon solicited wealthy businessmen to support its theatricals and other activities. Since World War II, this “official” bohemia has been composed of the city’s political and financial elite, along with some establishment writers and commercial artists. Members meet in town (to hear readings of poetry by the likes of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Edwin Markham) and also at the Bohemian Grove, a notoriously exclusive retreat on the Russian River that hosts an annual summer exercise in ruling-class cohesiveness, where CEOs and directors of the Fortune 500 companies camp out in secrecy with presidents and congressmen, cabinet members, and Pentagon brass. (Domhoff 1974)

After the Carmel experiment foundered, Sterling returned to San Francisco, depressed and feeling isolated. His hopes for a literary community were dashed and his ornamented verse failed to find favor in the East. He committed suicide in the Montgomery Block in 1927. That same year the poet Kenneth Rexroth arrived in San Francisco in quite a different mood, delighted to find a literary scene so underdeveloped and noncommercial—an inviting tabula rasa. Neither the modernism of Eliot and Pound nor the latest critical fashions had reached the city, which despite its pretensions was in the late 1920s a real cultural backwater. Rexroth, with his wide-ranging intellect, prodigious memory, and ferocious temper, believed himself just the man to transmute the city’s literature and culture along radical new lines. Rexroth had come out of the anarchist tradition of socialism and during the Depression worked as a labor organizer and for various WPA projects; he was active with the Randolph Bourne Council, the John Reed Clubs, and the Waterfront Workers Association. An admirer of Kropotkin’s Ethics and Mutual Aid, he was a fiery advocate of a communalist society that would be created through civil disobedience. Rexroth opposed European cultural chauvinism, and introduced translations of Asian poetry to American readers. Confronting the Eastern literary establishment, which was by the 1940s immersed in formality, ironic distance, and a value-free aesthetic, he insisted that poetry should have moral significance and bear personal witness against the “permanent war state.” Rexroth’s “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” a polemic against consumer culture, was a precursor to Ginsberg’s “Howl”—but was much more vitriolic.

Office workers of the 1940s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

After World War II, the United States began to solidify its enlarged role as an imperialist power and to incorporate useful features of fascism: militarization, nationalist ideology, state support of large corporations (“What’s good for General Motors is good for America”), and the creation of enemies for purposes of social control. The mass media celebrated common sense, social adjustment, conformity, churchgoing, and togetherness. The good life was defined by a house in suburbia, a new car, and synthetic products; the economics of planned obsolescence fanned the flames of market growth. Blacks who had served in the armed forces were mustered out to segregated neighborhoods, and women who had worked in war industries went to the new suburbs to be housewives, childbearers, and the principal victims of restored sexual puritanism.

However, returning GIs brought home with them a new interest in foreign cultures, and San Francisco, with an eye on potential markets abroad, stepped up its commercial contacts with Asia. In fact, the city then was receptive to many outside cultural influences and offered a receptive environment for radicals, anarchists, communists, populists, Wobblies, abstract expressionist painters, assemblage artists, and experimental theater troupes. Jazz and bebop began revolutionizing music and pulling in enthusiastic crossover audiences. And behind the rhetoric of consumerism and togetherness a current of dissent ran just below the surface. Philip Lamantia recalled the city in the late 1940s:

San Francisco was terribly straight-laced and provincial, but at the same time there were these islands of freedom—in North Beach at bars like the Iron Pot and the Black Cat, where intellectuals met to talk. There was a whole underground culture that went unnoticed by the city at large. An amazing music scene was going on, black music. Ebony magazine ran a story about how San Francisco was the best city in the country for blacks. Down in Little Harlem around Third Street and Howard you could hear all-night rhythm and blues. The Fillmore was the center of the bebop revolution, with frequent appearances by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and San Francisco was unique for the open and friendly relations between blacks and whites who had gone underground, much more so than in New York. Blacks accepted the white hipster poets, and the musicians generously let a few talented young white musicians jam with them.

Writers who were conscientious objectors during World War II and interned at the Waldport, Oregon, CO camp came down on furlough to meet with Bay Area writers. Among them were Adrian Wilson, an innovative fine press printer, and the poet William Everson, whose Untide Press published Kenneth Patchen’s poetry of social protest. Between 1946 and 1952, Rexroth held Friday evening soirées at his home at 250 Scott Street to discuss poetry and ideas. Regular participants included William Everson, Robert Duncan, Philip Lamantia, Muriel Rukeyser, Morris Graves, Gary Snyder, James Broughton, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, and Thomas and Ariel Parkinson. (Hamalian 1991)

Additionally, the anarchist Libertarian Circle met on Wednesdays on Steiner Street, where a community of free spirits drank plenty of red wine and set about refounding the radical movement. They met for big parties at Fugazi Hall on Green Street in North Beach, and the writers and artists of the Rexroth group were joined by old Italian anarchists, longshoremen, doctors, cabbies, professors; sometimes as many as two hundred people attended these gatherings, which featured political debate, dancing, picnics, and hiking trips. Out of this Libertarian Circle came Lewis Hill, who conceived the idea of a listener-sponsored, cooperative radio station as a means to reach greater numbers of people. He and Richard Moore aspired to make available a life of the mind for working people who couldn’t afford a university education. Thus was born KPFA/Pacifica, which aired experts on public affairs and philosophy, literature and film, classical music and jazz, expanding the social influence of the region’s progressive intellectuals.

Literature began to be a communal experience, with poetry readings and discussions drawing substantial audiences. Regular readings were organized at San Francisco State College by Robert Duncan and Madeleine Gleason, and in 1954 Ruth Witt-Diamant formalized them with the foundation of the San Francisco Poetry Center there. English professor Josephine Miles coordinated similar events in Berkeley, and the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) was a center for literary performances as well. Spirited literary journals sprang up on both sides of the Bay: Goad, Inferno, and Golden Goose. George Leite published Circle magazine (1944–1948), influenced by surrealism, which attempted a new synthesis of antiauthoritarian politics, pacifism, and internationalism in letters. The Ark urged spontaneous revolt in order to transform social relations. This constellation of political engagement and literary expression became known as the San Francisco Renaissance, and it marked the beginnings of a shift of cultural gravity from East to West.

In 1947 Harper’s published an article by Berkeley writer Mildred Edie Brady, “The New Cult of Sex and Anarchy,” which unwittingly drew national attention to the Bay Area’s special appeal. She took a dim view of the region’s art and intellectual life, describing two camps of bohemians. The first, she said, were devotees of Henry Miller who were attracted by the sex in his books and by his pacifist manifesto, “Murder the Murderers”; they were embroiled in “mysticism, egoism, sexualism, surrealism, and anarchism.” The second group could be found in association with Kenneth Rexroth: these read Peter Kropotkin and Wilhelm Reich. Both groups, she reported, glorified the irrational and did nothing but count their orgasms. Two young New York writers, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, would remember this summons to possibilities far more appealing than Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity and the agenda of the New Criticism.

The principal writers of the Beat Generation—Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and Jack Kerouac—had met in New York City in the early 1940s, when Ginsberg and Kerouac were students at Columbia University. They were experimenting with new writing based on uncensored self-expression and altered states of consciousness induced by trance or drugs. Joined by Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso, and Herbert Huncke, they hung around Times Square, fascinated by marginal subcultures, and picked up the style and language of addicts, con men, carnies, hustlers, and small-timers. (Schumaker 1992) In the world of the dispossessed urban dweller they saw an escape from postwar mass society. These Easterners were disaffected, urban, noir, while the poets of what would later be considered the Bay Area branch of the Beat Generation—Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia, David Meltzer, Joanne Kyger, Bob Kaufman, Michael McClure, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Philip Whalen—were more politically and ecologically oriented. And while the vitality of African American culture influenced writers on both coasts, the Western poets were more open to Asian and Native American traditions.

The poet hipsters converged in San Francisco in the mid-fifties, when, for a brief few years, an energetic literary community produced readings, small publications, and multimedia events in collaboration with assemblage artists Jay de Feo, Wally Berman, Joan Brown, Wally Hedrick, and Bruce Conner. (Solnit 1990) Lawrence Ferlinghetti had come from Paris to San Francisco in 1950, where he met Peter D. Martin, son of the anarchist Carlo Tresca, and together they founded the City Lights Bookstore in 1953 as a literary meeting place. Two years later Ferlinghetti issued his first book of poems, Pictures of the Gone World, launching City Lights Publications. Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady sped back and forth between New York and San Francisco, measuring the disappearing landscape of freedom, an experience portrayed in Kerouac’s novels. With the publication of On the Road in 1957 the Village Voice noted that “Jack Kerouac, the Greenwich Village writer (with Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso), had to go to San Francisco to become a San Francisco writer and become famous.” Ginsberg arrived in 1954 and wrote “Howl” that same year and the next, while living at 1010 Montgomery Street in North Beach. Ferlinghetti had rejected Ginsberg’s earlier poems, but when he heard Ginsberg read “Howl” at the Six Gallery in 1955, he knew it was the defining poem of the era. This long incantatory work describes the destruction of the human spirit by America’s military-industrial machine and calls for redemption through the reconciliation of mind and body, affirming human wholeness and holiness.

Howl and Other Poems, which City Lights had had printed in England, came to public notice after the second edition was seized by U.S. customs in March 1957 on charges of obscenity. On April 3 the American Civil Liberties Union (to which Ferlinghetti had submitted a copy of the manuscript before it went to the printer) informed Chester MacPhee, Collector of Customs, that it would contest the legality of the seizure. City Lights announced that a new edition of Howl was being printed in the United States, thereby removing it from customs jurisdiction. A photo-offset edition was placed on sale at City Lights bookstore and distributed nationally. On May 19, the San Francisco Chronicle printed a defense of the book by Ferlinghetti, who stated, “It is not the poet but what he observes which is revealed as obscene. The great obscene wastes of Howl are the sad wastes of the mechanized world, lost among atom bombs and insane nationalisms.” Customs released the books, but then the local police took over, arresting Ferlinghetti and the bookstore manager, Shigyoshi Murao, on charges of selling obscene material.

A long court trial lasted throughout summer, during which City Lights and Howl were supported by poets, editors, and critics. J. W. Erlich, an attorney of national renown who had defended Billie Holiday and other artists, agreed to take the case, along with Albert Bendich and Lawrence Speiser of the ACLU. (Erlich 1960) When it was learned that Municipal Judge Clayton Horn, a devout Christian who taught Bible classes, had been appointed to hear the case, Ferlinghetti’s lawyers foresaw trouble. It was unusual for the Municipal Court to hear constitutional cases, and Horn took his responsibility seriously, especially in the wake of his previous case. Several young girls visiting the city from Los Angeles had been caught shoplifting, and Judge Horn had sentenced them to read passages from the Bible and to see Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, which was filmed partly in San Francisco and had just been released. The sentence provoked a great public outcry: Judge Horn had violated the principle of separation of Church and State. So Horn asked for a recess so he might read other obscene books that had been banned throughout history, and then proved himself a conscientious man, determining that Howl was not obscene because it was “not without socially redeeming importance.” He then went on to set forth certain rules for the guidance of authorities in the future, establishing the legal precedent that enabled publication in the next decade of Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, and other prohibited literary works.

Like Mürger’s book about Paris bohemians, the novels of Jack Kerouac chronicled the half-imagined, half-real lives of the artists. His On the Road and Ginsberg’s “Howl” seemed to awaken the collective American id, arousing desire and fear, rage and envy. To the astonishment of the poets, who were going about their work writing poetry and editing small literary journals, the Luce empire unleashed its full arsenal at a perceived challenge to the Puritan ethic. The beat poet was excoriated as juvenile delinquent, drug addict, and sexual outlaw. In one piece, Life magazine asserted that “bums, hostile little females and part-time bohemians are foisted into polite society by a few neurotic and drugged poets. . . . [They are] talkers, loafers, passive little con men, lonely eccentrics, mom-haters, cop-haters, exhibitionists with abused smiles and second mortgages on a bongo drum—writers who cannot write, painters who cannot paint, dancers with unfortunate malfunction of the fetlocks.” Paul O’Neil wrote a piece in Life called “What Is It That Beats Want?” paraphrasing Freud’s famous question about women, noting that the beats, too, were illogical, emotional, and irrational. Things went so far that at the 1960 Republican Convention FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover warned that America’s three greatest enemies were Communists, Eggheads, and Beatniks.

Beatnik parade downtown in Union Square, August 13, 1958.

Photo: Bancroft Library

A cry of outrage came from yet another quarter: establishment intellectuals disliked beat populism and the lack of respect for tradition, the latter a complaint that continues in academia today in new guise in the debates over multiculturalism, curriculum, and the canon. Writers Herb Gold, James Dickey, and John Updike attacked the beats; and Diana Trilling labeled them “unholy barbarians.” The poet and critic John Hollander saw in “Howl” the “ravings of a lunatic fiend,” and John Ciardi wrote in the Saturday Review: “The fact is that the Beat Generation is not only juvenile but certainly related to juvenile delinquency through a common ancestry whose name is Disgust . . . little more than unwashed eccentricity.” Norman Podhoretz was hysterical: “We are witnessing a revolt of all the forces hostile to civilization itself—a movement of brute stupidity and know-nothingism that is trying to take over the country. . . . The only art the new Bohemians have any use for is jazz, mainly of the cool variety. Their predilection for bop language is a way of demonstrating solidarity with the primitive vitality and spontaneity they find in jazz and of expressing contempt for coherent, rational discourse. . . .” This diatribe calls up the usual racist stereotypes in its comparison of beats to African Americans, to whose marginalized culture the writers were much indebted, as they openly claimed. Conservatives nearly a half century later are still sputtering about those who make careers of “execrating American values,” as George Will observed in an April 1997 syndicated obituary of Allen Ginsberg. In September, New Criterion editor Roger Kimball said in the Wall Street Journal that “Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and the rest of the Beats really do mark an important moment in American culture, not as one of its achievements, but as a grievous example of its degeneration.”

Even the anarchist Paul Goodman, who was sympathetic to the beats and applauded their “dropping out of the system of sales and production,” regretted that “They have no moral code, no positive political or social program, are merely the symptom of the failure of industrial society to provide a challenge to the young.” (Goodman 1959) He went on to regret the beats’ cynicism, neglect of ethical goals, and ignorance of civilized values. Radicals of the old left (many of them now of the new right) opposed the beats’ apolitical stance and their anarchist views. “[They] are only reflections of the class they reject,” wrote Irving Howe in the New Criterion, and he attacked them for having no political program. Indeed, the beats had no programmatic politics and rejected institutional forms of protest, declining party memberships and sect affiliations altogether.

Countercultures offer an irresistible narrative opportunity, with a colorful cast of characters and the seductive themes of transgression, exile, and utopia. The beat story, set in San Francisco, New York, and the long American highway in between, is part fiction, part autobiography—a narrative in the counterpoint voices of author and media. With a nice blend of condescension and malice, Chronicle columnist Herb Caen coined the word “beatnik” after the 1957 launch of the Russian satellite sputnik, conferring on the writers just a hint of anti-Americanism. A city reporter dressed in all-black, donned beret and false beard and went to the pads of North Beach to report on the exotic sexual practices of the misfits. (Watson 1995) All this coincided with the inordinate attention sociologists were then giving to alienated youths stuck at the “aggressive stage,” and doomed to be social pariahs. The juvenile delinquent was being represented in an exciting way in such films as The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1959). A film company offered Kerouac and Cassady a huge sum of money (which they refused) to pose as armed and vicious killers to promote a beatnik genre film: Albert Zugsmith’s The Beat Generation featured a sociopathic rapist pursuing suburban housewives. Exploitation novels had such titles as Lust Pad, Bang a Beatnik, and Sintime Beatniks. The popular sitcom The Lives and Loves of Dobie Gillis introduced the unthreatening beatnik for family consumption in the goateed Maynard G. Krebs, a figure reprised in the 1980s in Happy Days as “the Fonz.” For the kids there was even a muppet called Ferlinghetti Donizetti (“I don’t wash. I don’t have to!”). Press coverage finally brought young people to North Beach from all over the country; they dressed as hipsters and tried to be beats; they were followed by tourists who came to see beatniks; and finally, commodities were created to sell to both beatniks and tourists. This commercial appropriation would be replicated a decade later in the Haight-Ashbury, with the hippies.

By the time the Coppolas began working on their definitive film of On the Road in the early nineties, the beat writers had become subjects of doctoral dissertations and as iconic as the city that claimed them for itself. A San Francisco Examiner story, “Icons” (Nov. 1996), noted “the cultural detritus” being exhibited at museums: art works featuring Elvis, Marilyn, Lucy, and “Beat Culture and the New America: 1950–1965,” which had shown the year before at the Whitney in New York. “Whether it’s Dennis Hopper’s photos of alienated youths, Michael McClure, Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg gathering in hip colloquy or a slouching Jack Kerouac, the Beat attitude is integral to the Bay Area’s identity.” Billboards of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac in Gap khaki have loomed over the downtown freeway, while William Burroughs was pictured in Vanity Fair in Nikes. Major corporations regularly solicit the City Lights Bookstore for location shots against which to display their products. In efforts to turn the neighborhood into a theme park, the North Beach Chamber of Commerce modified its logo to “Little Italy and the Home of the Beat Generation.” A recent float in the Italian Heritage Parade (formerly the Columbus Day Parade until Native American protesters motivated a name change) revives the stereotypical image of the “beatnik” with beret and bongos. In fact, a steady exodus of Italians from North Beach to the Marina, the Mission, and the Excelsior has been going on since the 1906 earthquake, making “Little Italy” a misnomer today. And although a bohemian community established itself in North Beach, with coffee houses, galleries, and the City Lights bookstore as pivot points, the brief period of close collaboration of beat writers and artists was over by 1956, when Ginsberg, Burroughs, Kerouac, and others left San Francisco, just as North Beach was moving center stage in the public mind.

The beats succeeded surprisingly well, however, in sidestepping mainstream appropriation. For one thing, they were not a school; formal stylistic agenda was something they avoided. For another, they were more a historical moment than a cohesive literary movement in which Ferlinghetti’s Chaplinesque populism could coexist with William Burroughs’s paranoid dystopia or Philip Lamantia’s urban surrealism with Gary Snyder’s bedrock common sense. Moreover, most of the Western writers never identified themselves as “beats” at all. We see over the years that a succession of independent press publications and loosely organized readings and other events brought together writers who were distinctly individual in aesthetic sensibility, subject matter, and personal interests. The beats marked a point of transition between the old bohemian utopias and the postmodern era of decentralization and “difference.” The writers had the advantages of both mobility and a unifying narrative. Ginsberg’s resolute vision of a community of poet comrades and his energetic media skills perpetuated the larger story of a “generation” with a common agenda, which helped to focus attention on the writers and to give them a public forum. However, the wide compass and heterogeneity of the beats was fundamental to their far-reaching appeal: Diane di Prima’s feminism, Phil Whalen’s zen whimsy, Bob Kaufman’s dada black humor, Jack Kerouac’s apolitical romances. City Lights, too, played a role in widening the definition of “beat.” Ferlinghetti, who never considered himself a beat writer, saw the group as part of a larger, international, dissident ferment. His idea was to encourage crosscurrents and cross-fertilizations among writers and thinkers from different cultures and communities both in the books sold at the store and in its publication program. In this sense the beats are just one phase of the outsider literary line, and “the beat goes on” in City Lights’ books and journals that presented such younger writers as Anne Waldman, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Sam Shepard, Sara Chin, Andrei Codrescu, Karen Finley, Ellen Ullman, James Brook, Rodrigo Rey Rosa, Charles Bukowski, David Henderson, Gary Indiana, Ward Churchill, Michael Parenti, Alberto Blanco, Rebecca Brown, Janice Eidus, Gil Cuadros, Jeremy Reed, Nathaniel Mackey, La Loca, Rikki Ducornet, and Peter Lamborn Wilson.

With no set allegiances to political parties or agendas, the beats were important as exemplars of creative resistance. As Allen Ginsberg often claimed, candor—the expression of authentic personal experience—was foremost, and beat work helped to bring private life into public discourse. The beat challenge to power was in the practice of a kind of mobile guerrilla poetics. Because the beat period is usually dated 1945 to 1960 (or 1965), the writers’ mature years are seldom taken into account, the years in which they were most active in national and community issues, especially Ferlinghetti, Snyder, Ginsberg, and di Prima, who had moved permanently to San Francisco in the early 1970s. Snyder was a leading force in the back-to-the land ecology movement. Di Prima taught in schools and prisons and founded a school of healing arts. San Francisco’s poets gave benefit readings, marched and demonstrated and sometimes went to jail. Some were active in support of the United Farm Workers and other union struggles; others were at the forefront of protests of the Vietnam War and, later, U.S. military and CIA interventions in Latin America. Allen Ginsberg was a Pied Piper of poetic interventions: levitating the Pentagon in 1967 and chanting with the Yippies at the 1968 Democratic Convention, and then testifying with humor and common sense at the ensuing Chicago Conspiracy Trial. He spent many years documenting evidence of CIA drug dealing. On one stay in San Francisco in the mid-seventies, he so pestered CIA chief Richard Helms on the telephone that Helms made a bet with him. He promised to investigate Ginsberg’s charges and vowed that if Ginsberg proved to be right about the agency’s heroin trafficking he would meditate every day for the rest of his life. Within a couple of days, the City Lights publishing office received a call from Helms: “Please tell Mr. Ginsberg that I began my first meditation session this morning.” Another prolonged investigation that Ginsberg undertook with PEN American Center uncovered reams of documents proving extensive FBI sabotage and destruction of the independent press that had been a vigorous force in the 1960s and 1970s. (Rips 1981)

The “rucksack revolution” Kerouac had prophesied in The Dharma Bums arrived in the Bay Area in the early 1960s. Once again, a new music—this time rock—drew a new generation of rebellious youths to San Francisco. The hopes of this massive counterculture to enlighten national consciousness through a psychedelic-erotic politics eventually proved futile. Although breakthroughs were made in sexual liberation and the arts, particularly multimedia and performance work, the community self-destructed under the weight of Dionysian excess, political naïveté, and the impossibility of creating a utopia that would serve macrocosmic needs. As in other bohemias, a society of dropouts is never as free as it seems and cannot exist outside the organized catastrophe of oppression. This later became clearer as the numbers of the hippie counterculture grew. (Smith 1995)

A post-hippie underground sensibility emerged in the early seventies in the social-critique proto-performance work of such artists as Sam Shepard, Karen Finley, and in projects by filmmakers and photographers at the San Francisco Art Institute. At the Mabuhay Gardens later in the decade punk musicians began mocking the star system of stadium rock and repossessing their own creativity. V. Vale perceived in the punks a healthy defiance of commercial youth culture and, with seed money from Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti, began documenting (and catalyzing) this impetus in his tabloid Search and Destroy and in the publications of Re/Search, which covered—in addition to the punk scene—reggae, situationism, surrealism, marginalized artists, and the particular legacies of Burroughs, Lamantia, and J. G. Ballard.

By the mid-seventies, oppositional communities began to be based on gender and ethnicity. “Difference” was the focus, and difference no longer referred to white male bohemians dropping out of mainstream society, but instead to perceived “genetic” difference. (Davidson 1989) Aware of multiple histories, writers grouped themselves as gays or lesbians, Latinos, blacks—with subdivisions within those groups. Ethnic writers and artists gathered in the neighborhoods to explore issues of identity and to foster small-group cohesiveness. Such groups as the Kearny Street Workshop and the Mission Raza Writers in San Francisco and the Before Columbus Foundation in Berkeley discovered and published fresh ethnic voices who had different stories to tell and had never had the opportunity to be heard. Interlingual poetry flourished, as did new performance work. These developments were instrumental in alerting New York publishers to a substantial new audience they had scarcely touched. In the eighties, a new formalism began to obscure the popular voice. In the ferment of deconstruction and postmodern theory, elitist language and theory in the universities began to dominate as they had in the 1950s. Globalized ideologies make pluralism and diversity useful in eluding appropriation, but the doctrine of fragmentation and decentralization makes problematic recognizing and acting on common interests. It is instructive to note that when the Berlin Wall fell, East German Stasi (secret police) documents revealed that the government had paid agents to infiltrate the literary underground in order to put an end to beat-inspired writing by subsidizing “pomo” theory and the new formalism, which was believed could divert attention from social issues.

The renewed popularity of the beats in the nineties goes beyond nostalgia for a period that now seems innocent in its freedom of the road and for its pleasures of unrestrained sex and drugs. The 1950s and 1990s have much in common, both periods characterized by paradigmatic technological and economic change, government capitulation to corporate power, the rise of religious fundamentalism, and a media-imposed anti-intellectual culture. Public resources for education, libraries, and the arts have been savagely curtailed, bringing to crisis a long period of cultural vigor in the Bay Area. An oppositional culture today faces formidable challenges now that the global economy has transformed work and the dynamics of urban life. In San Francisco, as elsewhere, upscale development, real estate speculation, and consequent high rents make the marginalized life of the independent writer and artist almost impossible. Additionally, the commodification of transgression and the instant appropriation, re-formation, and marketing of dissent have eliminated older channels of social contention. While the much-heralded democracy of electronic communication makes it easier to disseminate radical ideas, they are more easily drowned out in the glut of information pouring through the Babel of the Internet. Corporatization of bookselling and publishing also contribute to the dumbing-down effect. Fortunately, many people in San Francisco and the Bay Area have resisted the lure of Starbucks-Best-Seller culture, continuing to support independents. Talented writers and artists still manage to survive in the Mission and South of Market, producing experimental theater, performance works, digital arts, chapbooks, and zines; and so there remain in the city vital pockets of dissident culture that continue to confront the question of how to create art that uses anger and desire to motivate adventure, self-realization, and community. The future viability of this culture depends on what directions the city takes now.

References

Davidson, Michael. 1989. The San Francisco Renaissance: Poetics and Community at Mid-Century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Domhoff, G. William. 1974. The Bohemian Grove and Other Retreats; a Study in Ruling-Class Cohesiveness. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Erlich, J. W. 1960. Howl of the Censor. San Carlos, CA: Nourse Publishing Co.

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence, and Nancy J. Peters. 1980. Literary San Francisco. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Ginsberg, Allen. 1956. Howl and Other PoemsSan Francisco: City Lights.

Goodman, Paul. 1959. Growing Up Absurd. New York: Random House.

Halperin, Jon. ed. 1991. Gary Snyder: Dimensions of a Life. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Hamalian, Linda. 1991. A Life of Kenneth Rexroth. New York: W. W. Norton.

Rexroth, Kenneth. 1957. “Disengagement and the Art of the Beat Generation.” Evergreen Review 1, 2.

Rips, Geoffrey. 1981. Unamerican Activities: The Campaign Against the Underground Press. San Francisco: City Lights.

Schumaker, Michael. 1992. Dharma Lion: A Critical Biography of Allen Ginsberg. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Smith, Richard Candida. 1995. Utopia and Dissent: Art, Poetry and Politics in California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Solnit, Rebecca. 1990. Secret Exhibition: Six California Artists of the Cold War Era. San Francisco: City Lights.

Walker, Franklin. 1939. San Francisco’s Literary Frontier. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Walker, Franklin. 1966. The Seacoast of Bohemia; an Account of Early Carmel. San Francisco: Book Club of California.

Watson, Steven. 1995. The Birth of the Beat Generation; Visionaries, Rebels, and Hipsters, 1944–1960. New York: Pantheon.