Berkeley Barb and People's Park: Difference between revisions

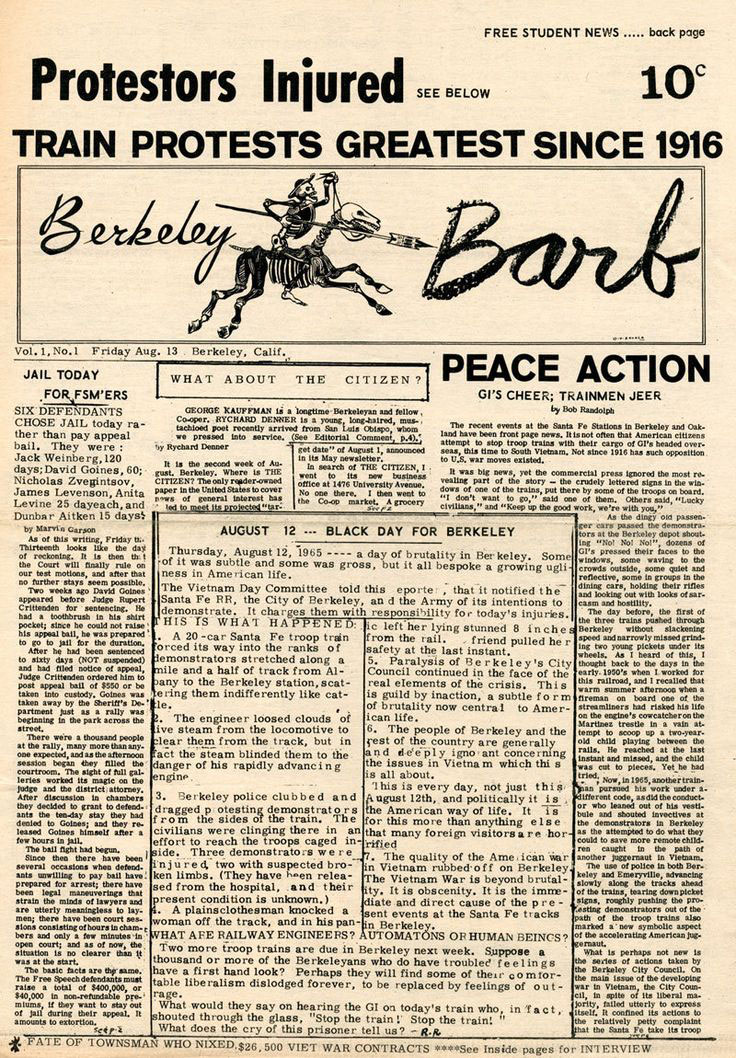

Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>"I was there..."</font></font> </font>''' ''by Lee Felsenstein'' Image:Barb-Vol-1-No-1.jpg '''Volume 1, No. 1 of the Berkeley Barb, 1965.''' In 1965 and 1966 I went every Thursday night to Pepe’s pizza parlor on Telegraph Avenue and, while enjoying a slice of pepperoni pizza, awaited my connection—a young fellow peddling a handful of thin (8 page) tabloid papers, one of which I would buy and read..." |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Later the following year I volunteered to help at the ''Barb'', following my path of exploration of media and ways in which I might apply my technical skills in developing such media. It was becoming clear to me that agora structures, such as the FSM had developed, would be the key to successful mass action and community formation—I had seen it happen. | Later the following year I volunteered to help at the ''Barb'', following my path of exploration of media and ways in which I might apply my technical skills in developing such media. It was becoming clear to me that agora structures, such as the FSM had developed, would be the key to successful mass action and community formation—I had seen it happen. | ||

I had become the editor and publisher of the 100-circulation weekly house newspaper of Oxford Hall, the co-operative residence hall where I was by then living. I implemented a free- speech policy of printing, unedited, any manuscript submitted so long as the author used their true name. This quickly created some controversy, and I felt it my responsibility to organize community reaction to egregiously offending authors rather than simply quashing their submissions as an editor normally would. Also, as a non-coercive editorial technique, I added footnote commentary to the articles. | I had become the editor and publisher of the 100-circulation weekly house newspaper of Oxford Hall, the co-operative residence hall where I was by then living. I implemented a free-speech policy of printing, unedited, any manuscript submitted so long as the author used their true name. This quickly created some controversy, and I felt it my responsibility to organize community reaction to egregiously offending authors rather than simply quashing their submissions as an editor normally would. Also, as a non-coercive editorial technique, I added footnote commentary to the articles. | ||

Of course, that was within a closed community with close, stable networks of relationships. What might be possible on a wider scale? My efforts to become a columnist at the campus newspaper came to nothing and I took my submissions to the ''Barb'', where I showed up on a deadline night. | Of course, that was within a closed community with close, stable networks of relationships. What might be possible on a wider scale? My efforts to become a columnist at the campus newspaper came to nothing and I took my submissions to the ''Barb'', where I showed up on a deadline night. | ||

Max Scherr, the editor and publisher, took time to read my samples and complimented me on good self-editing, offering me the opportunity to edit press releases down to the smallest possible length. My hope was that the Barb could become a community newspaper like the “throw-away” paper published in the large and cohesive Philadelphia Jewish neighborhood of my youth, filled with tiny items sent in by neighbors about local goings-on. | Max Scherr, the editor and publisher, took time to read my samples and complimented me on good self-editing, offering me the opportunity to edit press releases down to the smallest possible length. My hope was that the ''Barb'' could become a community newspaper like the “throw-away” paper published in the large and cohesive Philadelphia Jewish neighborhood of my youth, filled with tiny items sent in by neighbors about local goings-on. | ||

The ''Barb'', however, developed away from community information to an organ of spectacle and outrage—all of which was good for circulation and the bottom line. The ''Barb’s'' classified “relationship ads” brought in a lot of cash flow but attracted prostitution and institutional display advertising which grew into a large erotic display ad section that was even more lucrative. | The ''Barb'', however, developed away from community information to an organ of spectacle and outrage—all of which was good for circulation and the bottom line. The ''Barb’s'' classified “relationship ads” brought in a lot of cash flow but attracted prostitution and institutional display advertising which grew into a large erotic display ad section that was even more lucrative. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

I claimed a byline and an area of expertise by applying a practical viewpoint to commenting on demonstrations—I styled myself the “Barb Military Editor.” This began when I opened a press release we received from the ''USS Valley Forge'', an aircraft carrier at the nearby Navy base. It reported on the arrival of another ship from Vietnam, a “Landing Ship Dock” numbered 26. I wondered why we had received it, then looked again—LSD-26!—one digit beyond the scientific name of the “acid” drug LSD-25! I wrote an ironic piece which opened by reporting on the Navy’s rumored introduction of a new psychedelic drug into the area, spoiling the fun only at the end by pointing out that it was a warship. | I claimed a byline and an area of expertise by applying a practical viewpoint to commenting on demonstrations—I styled myself the “Barb Military Editor.” This began when I opened a press release we received from the ''USS Valley Forge'', an aircraft carrier at the nearby Navy base. It reported on the arrival of another ship from Vietnam, a “Landing Ship Dock” numbered 26. I wondered why we had received it, then looked again—LSD-26!—one digit beyond the scientific name of the “acid” drug LSD-25! I wrote an ironic piece which opened by reporting on the Navy’s rumored introduction of a new psychedelic drug into the area, spoiling the fun only at the end by pointing out that it was a warship. | ||

I published the piece under my newly invented byline, and a week later opened a letter from the press room at the Valley Forge, addressed to the Military Editor. It included a subscription and the news that my article had been the first time the non-military press had published any story based on their press releases. I continued to use the “Military Editor” title when writing about the reality versus the symbolism of demonstrations, especially in the pseudo-revolutionary milieu of the time where people could really get into trouble by confusing the two. Eventually I published a few longer pieces of my thoughts about organizing telephone trees, decentralized political networks of communal households, and dealing with wiretaps. Some of these articles later appeared in my FBI file. | I published the piece under my newly invented byline, and a week later opened a letter from the press room at the ''Valley Forge'', addressed to the Military Editor. It included a subscription and the news that my article had been the first time the non-military press had published any story based on their press releases. I continued to use the “Military Editor” title when writing about the reality versus the symbolism of demonstrations, especially in the pseudo-revolutionary milieu of the time where people could really get into trouble by confusing the two. Eventually I published a few longer pieces of my thoughts about organizing telephone trees, decentralized political networks of communal households, and dealing with wiretaps. Some of these articles later appeared in my FBI file. | ||

For the wiretap article I included as an insert a schematic diagram of a one-transistor oscillator that, when connected to a tapped phone line, would bedevil its tappers by constantly triggering their recorders when the phone was hung up (I had built and tested that circuit with great success). The insert was printed under a false name and point of origin, but I was in the office when a visitor asked me, “did you see the article by Felsenstein?” I replied “I am Felsenstein—how did you know it was me?” He replied that it was obvious—that only I could have written it. | For the wiretap article I included as an insert a schematic diagram of a one-transistor oscillator that, when connected to a tapped phone line, would bedevil its tappers by constantly triggering their recorders when the phone was hung up (I had built and tested that circuit with great success). The insert was printed under a false name and point of origin, but I was in the office when a visitor asked me, “did you see the article by Felsenstein?” I replied “I am Felsenstein—how did you know it was me?” He replied that it was obvious—that only I could have written it. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

For two weeks the city was under a form of military occupation, though without live ammunition. Agitators took the line that the Guardsmen were not the enemy like the sheriffs were, and local girls eroded morale by propositioning the Guardsmen, in a dress rehearsal for actual occupation. Symbolic actions raged back and forth, with young people planting saplings at unauthorized sites and the police arriving to disperse them and tear out the plants, providing a nearly perfect metaphor for ecologically-based community revolt. | For two weeks the city was under a form of military occupation, though without live ammunition. Agitators took the line that the Guardsmen were not the enemy like the sheriffs were, and local girls eroded morale by propositioning the Guardsmen, in a dress rehearsal for actual occupation. Symbolic actions raged back and forth, with young people planting saplings at unauthorized sites and the police arriving to disperse them and tear out the plants, providing a nearly perfect metaphor for ecologically-based community revolt. | ||

[[Image:1969-National-Guard-on-Telegraph.jpg]] | |||

'''National Guard on Telegraph near Dwight, 1969.''' | |||

''Photo: TelegraphBerkeley.org'' | |||

At one point a National Guard helicopter discharged tear gas from the sky over the campus. I was below directing people to clear out of a surrounded campus area which emptied by the time the attack took place. The gas drifted over half the city of Berkeley and raised major community hostility against the occupation. | At one point a National Guard helicopter discharged tear gas from the sky over the campus. I was below directing people to clear out of a surrounded campus area which emptied by the time the attack took place. The gas drifted over half the city of Berkeley and raised major community hostility against the occupation. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 63: | ||

'''People's Park poster''' | '''People's Park poster''' | ||

''Photo: Berkeleybarb.net'' | |||

''(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)'' | |||

[[Working at Ampex|previous article]] • [[Founding of Ohlone Park|continue reading]] | [[Working at Ampex|previous article]] • [[Founding of Ohlone Park|continue reading]] | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

| Line 68: | Line 77: | ||

''Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future'' | ''Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future'' | ||

by Lee Felsenstein | by Lee Felsenstein | ||

published by [https://www.FelsenSigns.com FelsenSigns] | published by [https://www.FelsenSigns.com FelsenSigns] | ||

[[category:East Bay]] [[category:media]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:anti-war]] [[category:military]] [[category:newspapers]] [[category:Dissent]] | [[category:East Bay]] [[category:media]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:anti-war]] [[category:military]] [[category:newspapers]] [[category:Dissent]] [[category:Book Excerpts]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:08, 15 June 2025

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

Volume 1, No. 1 of the Berkeley Barb, 1965.

In 1965 and 1966 I went every Thursday night to Pepe’s pizza parlor on Telegraph Avenue and, while enjoying a slice of pepperoni pizza, awaited my connection—a young fellow peddling a handful of thin (8 page) tabloid papers, one of which I would buy and read with great interest. This was the Berkeley Barb, the third “underground paper” in the US, published out of a house a mile away by a former lawyer who had operated a bar in Berkeley. It reported on the growing anti-Vietnam war activities and other events of interest to the developing “underground” community. Marvin Garson, whose analysis of the Free Speech Movement I had found so seminal, had a column which was generally the first item I read.

In the summer of 1965, while listening to radio reports of the perils experienced by civil rights workers in the South, I began to consider whether there could be such a thing as a nonviolent weapon which I might be able to develop for use in such environments. There were plenty of violent weapons down there and nothing I could invent would change that, so I began to hypothesize something which could mark an attacker, thereby destroying the cover of anonymity under which racial terrorism was committed. I never pursued the development of any such device, but my thinking led me to an important conclusion—a nonviolent weapon would be an information weapon! From that time, I began to think about information networks and their structures.

Later the following year I volunteered to help at the Barb, following my path of exploration of media and ways in which I might apply my technical skills in developing such media. It was becoming clear to me that agora structures, such as the FSM had developed, would be the key to successful mass action and community formation—I had seen it happen.

I had become the editor and publisher of the 100-circulation weekly house newspaper of Oxford Hall, the co-operative residence hall where I was by then living. I implemented a free-speech policy of printing, unedited, any manuscript submitted so long as the author used their true name. This quickly created some controversy, and I felt it my responsibility to organize community reaction to egregiously offending authors rather than simply quashing their submissions as an editor normally would. Also, as a non-coercive editorial technique, I added footnote commentary to the articles.

Of course, that was within a closed community with close, stable networks of relationships. What might be possible on a wider scale? My efforts to become a columnist at the campus newspaper came to nothing and I took my submissions to the Barb, where I showed up on a deadline night.

Max Scherr, the editor and publisher, took time to read my samples and complimented me on good self-editing, offering me the opportunity to edit press releases down to the smallest possible length. My hope was that the Barb could become a community newspaper like the “throw-away” paper published in the large and cohesive Philadelphia Jewish neighborhood of my youth, filled with tiny items sent in by neighbors about local goings-on.

The Barb, however, developed away from community information to an organ of spectacle and outrage—all of which was good for circulation and the bottom line. The Barb’s classified “relationship ads” brought in a lot of cash flow but attracted prostitution and institutional display advertising which grew into a large erotic display ad section that was even more lucrative.

By way of contrast, my attention was drawn to the page in each issue where notices of events were posted for free—the “Scenedrome.” This was the remaining vestige of the community-based information exchange into which I had hoped the Barb would evolve. This would become significant later.

I claimed a byline and an area of expertise by applying a practical viewpoint to commenting on demonstrations—I styled myself the “Barb Military Editor.” This began when I opened a press release we received from the USS Valley Forge, an aircraft carrier at the nearby Navy base. It reported on the arrival of another ship from Vietnam, a “Landing Ship Dock” numbered 26. I wondered why we had received it, then looked again—LSD-26!—one digit beyond the scientific name of the “acid” drug LSD-25! I wrote an ironic piece which opened by reporting on the Navy’s rumored introduction of a new psychedelic drug into the area, spoiling the fun only at the end by pointing out that it was a warship.

I published the piece under my newly invented byline, and a week later opened a letter from the press room at the Valley Forge, addressed to the Military Editor. It included a subscription and the news that my article had been the first time the non-military press had published any story based on their press releases. I continued to use the “Military Editor” title when writing about the reality versus the symbolism of demonstrations, especially in the pseudo-revolutionary milieu of the time where people could really get into trouble by confusing the two. Eventually I published a few longer pieces of my thoughts about organizing telephone trees, decentralized political networks of communal households, and dealing with wiretaps. Some of these articles later appeared in my FBI file.

For the wiretap article I included as an insert a schematic diagram of a one-transistor oscillator that, when connected to a tapped phone line, would bedevil its tappers by constantly triggering their recorders when the phone was hung up (I had built and tested that circuit with great success). The insert was printed under a false name and point of origin, but I was in the office when a visitor asked me, “did you see the article by Felsenstein?” I replied “I am Felsenstein—how did you know it was me?” He replied that it was obvious—that only I could have written it.

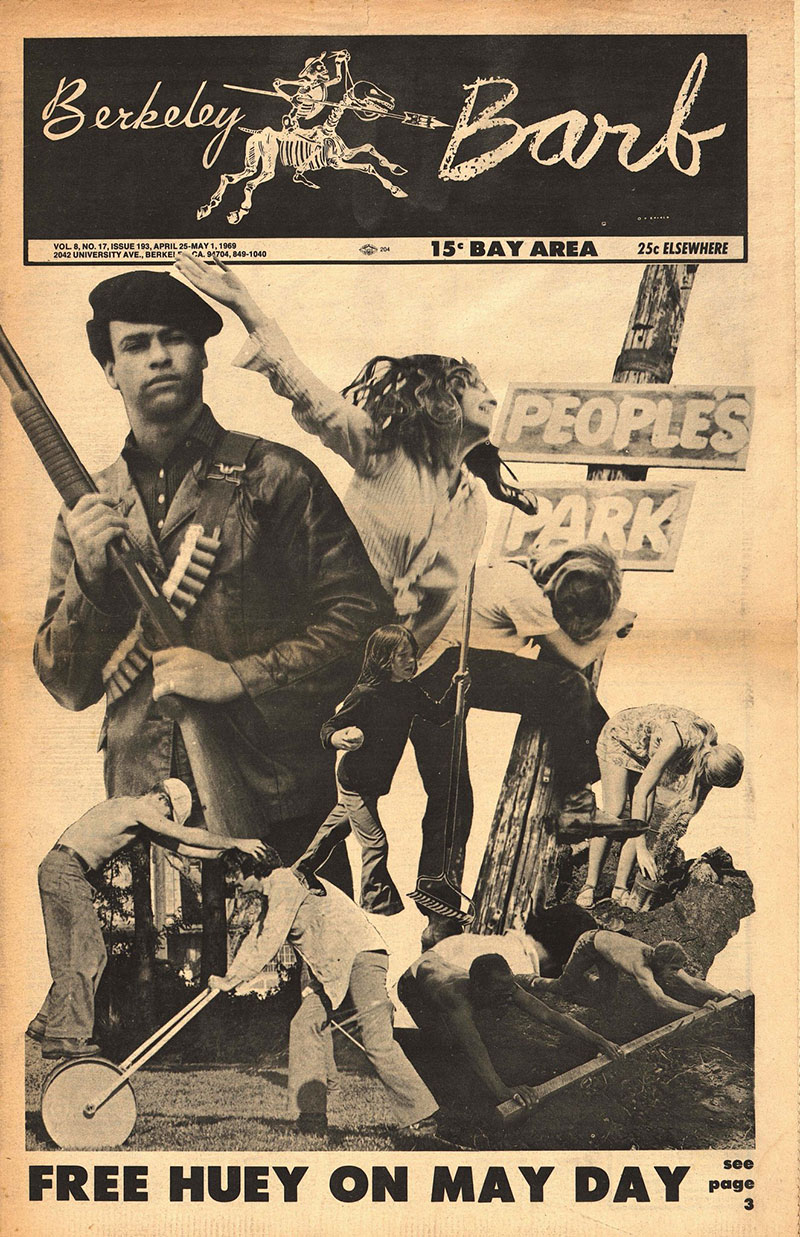

People's Park

In 1969, the “People’s Park” mini eco-revolt took place. The University had demolished a block of houses near campus that had been inhabited by the sort of people—students and former students—who had been stalwarts of the Free Speech Movement and subsequent antiwar activity. It was a ham-handed “urban renewal” solution to having the wrong type of people around.

Funding evaporated at that point and the block became an unfenced mudhole used as an informal, uncontrolled parking lot. A local radical, unencumbered by any organization, declared that the land must be reclaimed as a park and community area for the young hippies and runaways who had gravitated to the Telegraph Avenue area. Everyone was invited to participate in the renovation project, which began with an announcement in the Barb and the purchase of a truckload of sod.

At a time when the Vietnam war was reaching a maddening peak this provided an outlet for the energy of a lot of young people, who came together now with a focus of creating something that appeared to breach the boundaries of property and bureaucracy and coalesce an instant community.

Unburdened by planning, the work surged back and forth. In one corner of the block people began digging, for what end they did not know. A large pit resulted, and at some point a large meeting was held to discuss what it should be, resulting in the pit being filled back in. The radical approach held that leadership was tyrannical and that people would organically become their own leaders.

The climax came on May 15, 1969, when the University erected a cyclone fence around the lot, and after a rally on Sproul Plaza a horde of angry young people headed down Telegraph Avenue to tear the fence down. A bloody riot ensued, with county sheriff’s deputies firing shotguns loaded with lethal ammunition at people. One was killed and another blinded—many were wounded. Street fighting ensued and spilled onto the campus. The National Guard mobilized that day, and that night I found myself merging through their convoy in an old Volkswagen microbus overloaded with bales of inflammatory Barbs.

For two weeks the city was under a form of military occupation, though without live ammunition. Agitators took the line that the Guardsmen were not the enemy like the sheriffs were, and local girls eroded morale by propositioning the Guardsmen, in a dress rehearsal for actual occupation. Symbolic actions raged back and forth, with young people planting saplings at unauthorized sites and the police arriving to disperse them and tear out the plants, providing a nearly perfect metaphor for ecologically-based community revolt.

National Guard on Telegraph near Dwight, 1969.

Photo: TelegraphBerkeley.org

At one point a National Guard helicopter discharged tear gas from the sky over the campus. I was below directing people to clear out of a surrounded campus area which emptied by the time the attack took place. The gas drifted over half the city of Berkeley and raised major community hostility against the occupation.

Resolution came on May 30, with a permitted march past the park (a contingent split off to lay sod on the street) and the establishment of a committee to negotiate with university and city authorities on the disposition of the land. The community had had its symbolic trial run of revolution, occupation, and resistance, and wisely everyone pulled back.

In the aftermath of People’s Park the staff of the Barb organized and tried to buy out the publisher but failed due to internal divisions. They set up their own paper, the Berkeley Tribe, excluding me in the process as I was considered too close to the publisher.

I was quickly asked to join, however, because I appeared to know more about the operations of the paper than most of them. The Barb was quickly sold to a fast-talking hustler who did not meet his payment schedule—it was eventually recovered by Max Scherr after a court case lasting more than a year.

People's Park poster

Photo: Berkeleybarb.net

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns