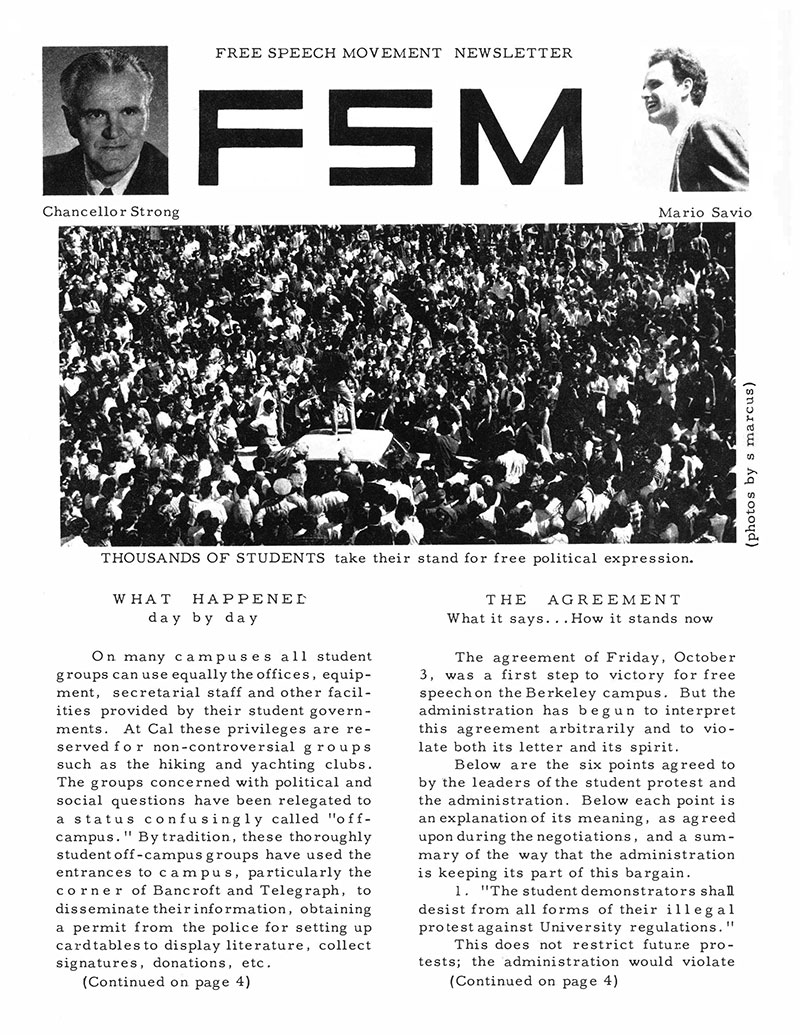

Free Speech Movement 1964

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

November 20, 1964: March to Regents' Meeting—L to R: Mona Hutchin, Ron Anastasi, ... John Leggett, John Searle, Michael Rossman, Jack Weinberg, Sallie Shawl, Mario Savio, Ken Cloke.

Photo: Bob Johnson photo © FSM Archives All rights reserved

My 1964 revolution was the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley—an outgrowth of the civil rights movement that “blew back” onto the University of California campus. That September administrators caved to local political pressure, trying to further restrict students’ political activity in support of demonstrations for equal employment opportunity that had broken out in the San Francisco Bay Area.

At that time Freedom Summer had wrapped up in the Deep South, with students straggling back to campus as battle-shocked veterans, telling stories of the terrorism and repression they had faced while helping with voter registration and literacy. No one was in any mood to yield an inch when the university declared off limits a strip of land apparently outside the campus limits that had served as the permitted site for tables used by political and civil rights groups. These tables were the connection point for a lot of students to the issues of the day and the events organized around those issues.

They were a crucial part of the fabric of communications among students with little time to spare for making and maintaining lines of communication. The university had some years before agreed to deed the land back to the city of Berkeley but no one had executed this move.

In any conflict, when your opposition attacks and disrupts your lines of communication you have to counter the move. The student political groups met and formed an umbrella organization—initially called "The United Front"—to protest and oppose the university's prohibition of using the land.

The organization included groups from across the political spectrum, from the Maoist Progressive Labor on the left to Students for Goldwater and Cal Conservatives for Political Action on the right. They adopted a position that UC, as a public university, should be bound only by the US Constitution—specifically the First and Fourteenth Amendments—when constraining speech on campus.

The administration took the position that “we’re in charge here—if you don’t like it, leave.” In nicer language to be sure, but in keeping with their power position based upon the legal concept of in loco parentis. Under this principle the university acted in place of the parents of undergraduate students, who at the time were legally minors (the age of majority then was 21). It was this paternalistic authoritarian order that was confronted by the Free Speech Movement.

The student groups, after some fruitless negotiations, went on the offensive and began committing civil disobedience—they set up tables well inside university property.

Fill the Jails

When administrators issued a citation to a student sitting at the table another would take their place. Some of those cited were called to the Dean’s office. All 150 who had been cited showed up and demanded to be punished—the classic "fill the jails" tactic. In the resulting chaos all were told to leave.

As this was happening the groups turned their information-dissemination efforts (a common function of them all) to publicizing the conflict, through leafleting. Then the administration did something spectacularly stupid: they called in the campus police.

Jack Weinberg, a former student and activist with Campus CORE (one of the civil rights groups that were staging demonstrations) and a recent graduate in mathematics, was cited at the table. The campus police were called to arrest him for trespassing—in an area traversed every day by tens of thousands of students. At noon, just when the lunch rush was about to begin, they brought up a police car to the center of the plaza and placed Jack in the back seat.

“Sit Down!”

From several throats in the crowd witnessing these events came the cry “sit down!” and the car was immediately surrounded first by scores and progressively by hundreds of seated protestors—as many as thousands at some times. The roof of the car soon became the podium of opportunity for various speakers seeking to explain the situation to bystanders and give their interpretations. The political groups had access to a public address system and quickly set up a microphone with speakers. Impromptu public free speech—prohibited by university regulations where political topics might be involved—had broken out as a direct result of efforts to prevent it. The sit-in went on day and night for 32 hours (Jack was occasionally escorted to a rest room when necessary but had every incentive to remain in the car otherwise).

October 1, 1964: Jackie Goldberg speaks atop police car.

Photo: © Ronald L. Enfield

The university president returned from a trip to Japan and negotiations began (as a faculty member his field had been labor negotiation). Parents' day was approaching and the matter came to a head on the second night with tough motorcycle police from the tough adjacent city of Oakland arriving in force, gunning their engines nearby.

An agreement was patched together that allowed Jack to go free without charges being filed, and the group’s leaders urged all those sitting in to leave peaceably. The issues were referred to several committees of faculty, including a new one. The horrible prospect of visiting parents finding a blood-soaked plaza was averted.

Free Speech Movement

That was October 2, 1964. The United Front retreated for a few days and constituted themselves as the Free Speech Movement, with the same program. “First and Fourteenth or Fight” sums it up. There followed a few weeks of negotiations that sometimes turned to farce. A faculty committee on student discipline mentioned in the agreement turned out not to exist, and the matter fell back into the administration’s hands. In the time-honored tradition of bureaucracies progress slowed to a crawl.

I was not present for all of this and had no idea what was happening. I had been in Southern California pursuing a work-study job that fell through and found myself bounced back to my old job on campus. The only mention I had seen of the whole affair had been a couple of articles in the Los Angeles papers about a “riot” on campus. The only photograph I saw showed the police car with students standing around it—I could not fathom why that counted as a riot. I arrived back on campus on October 16 and spent a week informing myself about the situation.

First issue of the Free Speech Movement newsletter

After that week I decided that the Free Speech Movement cause was worth supporting and I showed up at the house that held the headquarters of the “FSM” inquiring as to how I could help. I had a good-quality tape recorder and knew how to use it, so I was soon sent to the "press central”—a basement near campus. My idea for audio press releases came to nothing but I had skills operating mimeograph duplicators and could help with the one there which ran every night turning out leaflets.

The FSM carried on agitating and countering the administration’s moves until a climactic sit-in within the admin building on December 2 and 3 in response to their announcement ending negotiations. I was there at the noon rally in front of Sproul Hall when Mario Savio, our best orator and an original founder, gave the rationale in an immortal passage:

“There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart that you can’t take part—you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the wheels and the gears and levers and all the machinery and make it stop, and you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”

Mario Savio on Sproul Plaza, 1964.

Photo: TelegraphBerkeley.org

Over a thousand people, mostly students, surged into the building in an orderly fashion and occupied the hallways, closing it down for about 24 hours until hauled out by police on December 3. I was one and spent that evening in the Berkeley City Jail until vouched for by the professor who employed me.

On December 8 the Academic Senate met and debated the issue of speech on campus, concluding with a lopsided vote to support the position of the FSM. Much other drama surrounded all these events and can be researched on the web page of the Free Speech Movement Archives, which I founded in 1998.

The University Regents met and decided not to oppose the faculty position, while reserving the right to make the rules. The Free Speech Movement, its goals realized, dissolved itself as an organization in January, leaving behind a legal defense committee to handle the trials.

The World Opens

But nothing was the same on and around the campus. Thousands of students had tasted victory in a struggle that very few predicted would not meet a bad end. Ten thousand or more students, at least, had witnessed the mass of alienated students come together as a community to contend with and triumph over the vaunted university administration (which held the contract to administer the nation’s nuclear weapons research and development labs).

The political tables moved into the heart of the main plaza and proliferated. Innumerable students at Cal became engaged in changing their lives in small and big ways. I estimate that perhaps 5,000 dropped out to seek community elsewhere, thus seeding what eventually became the Haight-Ashbury community in San Francisco.

Some students started publishing an irreverent magazine about “Sex, Politics, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll (SPIDER). They had to take down their mobile of a huge spider, and the publication lasted perhaps 3 issues, but it was a prototype of publications like Rolling Stone—whose future publisher was on campus at the time.

I enrolled in a political science course and wrote a pamphlet on organization of a decentralized “Free University”. But the magical effect was the collective euphoria that seemed to permeate the environment (“Bliss was it...” as Wordsworth wrote of the French revolution in The Prelude). All seemed possible, and all were involved!

I believe that the Free Speech Movement was the proximate cause of the counterculture of the ‘60s, which spread from the San Francisco area to the world. At the time, I wanted urgently to do what I could to keep alive the sense of possibility—the enthralling realization that large numbers of people could move together to change the world in both large and small ways.

I had seen it! I had been one of those people! And I was in training to wield the most powerful tool available—technology. How then could I play a larger role in this process? Fortunately, I did not subsume my judgement to some organization but followed my nose and kept my eyes open.

Free Speech Movement executive committee meeting—L to R: Dunbar Aitkens, Brian Turner, Bill Mandel, man behind Bill, bearded man, man in tie, man with glasses, Bob Starobin, woman in glasses, Stevie Lipney, Brian Mulloney, man back to us, man in v-neck

Photo: courtesy fsm-a.org

I heard a significant part of the explanation soon after our December victory in a small forum addressed by Marvin Garson, one of the members of the Steering Committee of the FSM. In his analysis, the crucial fact was the lowering of barriers to communication among members of the campus community—the crisis enabled strangers to strike up conversations on the topic, and by so doing, create bonds that needed no intermediary structure. This analysis resonated with me.

The key was therefore the structure of communication among people, through non-hierarchical means (this excluded edited publications but included the telephone and postal media). Empower those means and the euphoria of the Berkeley experience could become permanent!

It was my first revolution, and it led me to participate in the longer, larger personal computer revolution that overturned the hegemony of the mainframe priesthood over information technology.

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

Excerpted with permission from:

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns

Lee Felsenstein (b. 1945) is an electronic design engineer who designed several early personal computer devices and who created the first public-access social media system. A veteran of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964, he embarked on a process of exploration of media intending to develop technology to enable the creation of communities. In 1970 he determined that this technology would be a network of computers, and in 1973 his project opened the first computer bulletin board for public use—Community Memory.

Realizing that personal computers would be necessary for a public system, Lee did some of the first design work on personal computers more than a year before the first personal computer was announced. He designed several of the first generation of personal computer products, including the first video text generator for personal computers, and the first successful portable computer.

He has been named a Fellow of the Computer History Museum (2016) in recognition of his pioneering efforts and continues his efforts at developing community-enabling designs.