Small Places Close To Home

Photo Essay

by Ken Stein… With a little help from Eleanor Roosevelt

All photos © by Ken Stein / All Rights Reserved

In a recent PBS American Masters episode “Janis Ian: Breaking Silence,” Ian said of her archives, “What I wanted them to do was to communicate a life, not my life, but the life of the times I lived in.” So it is very much in that spirit.

- —Ken Stein, July 2025

Eleanor Roosevelt at the United Nations, 1958.

Photo: United Nations

- Where, after all, do universal human rights begin?

- In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.

- Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood [she or] he lives in; the school or college [she or] he attends; the factory, farm, or office where [she or] he works.

- Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination.

- Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.

- Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.

- —Eleanor Roosevelt, speaking at the United Nations on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, March 27, 1958.

So where, after all, did disability civil rights begin? For many, they began in Berkeley and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Most of the photos here date from 1979-1989. For the Disability Rights Movement, these were key years of “l'entre-deux-guerres.” The years between the successful implementation of the “504” regulations in 1977—which ensured non-discrimination by entities receiving Federal Funds—and the successful passage of the ADA in 1990.

The 1980’s were a time when people with disabilities tasted and enjoyed the first fruits of Independent Living… of the 1977 implementation of both Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA); of de-institutionalization; of sexuality and parenting; and of integration in the community, in education, and in civic life.

It was also a time when disability advocates and activists from all over the country took to their legislatures, to the courts, and to the streets, demanding equal access and non-discrimination in areas not covered by 504—in stores, restaurants, hotels, access to housing, public transit, and private employment. Culminating in 1990 with the successful passage of the ADA, when for the first time ever, people with disabilities were granted their civil rights in virtually all areas of public life.

In the 1970s, Berkeley and the San Francisco Bay Area were widely recognized as being both the birthplace and spiritual center of the modern Independent Living Movement.

#A Brief History of the Bay Area Disability Rights Movement

In the 1980s, that message was carried into the schools and parks of Berkeley, and onto the streets of San Francisco.

And in fact, while it is true that much of the script of this early history had been written in Berkeley, much of the drama was played out on the streets of San Francisco.

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin?”

Adam Bertaina at Disabled Peoples’ Civil Rights Day March And Rally, San Francisco, October 20, 1979. “Keep Our Kids OUT Of State State Hospitals – Support Community Services”

Photo: © Ken Stein

A Gift Of History: Remembering Adam Bertaina

“In small places, close to home”

Replacement curb ramp being installed at Shattuck and University Avenue in Berkeley (1985).

Photo: © Ken Stein

“So close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.”

Ramp at the Ed Roberts Campus

Photo: © Ken Stein

“Yet they are the world of the individual person”

Sharon Hamner and her daughter in front of Hinks Department Store, Berkeley 1979.

Photo: © Ken Stein

A Gift of History – The High Cost of No Curb Ramps: Remembering Sharon Hamner

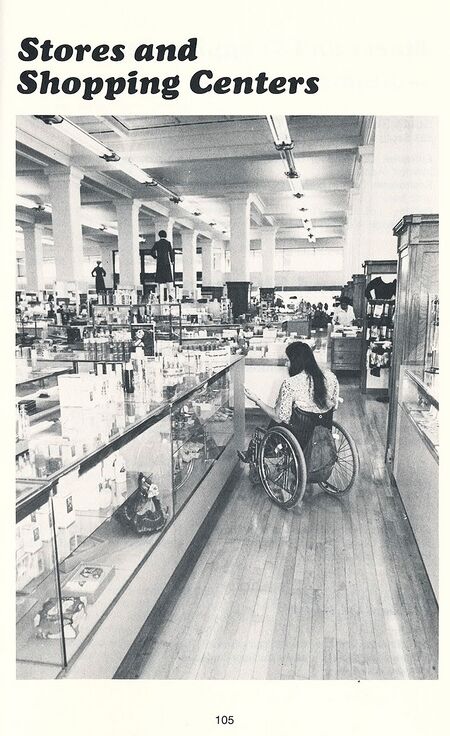

Marilyn Golden at Hinks Department Store in downtown Berkeley. From “Let Your Fingers Do The Walking: A Wheelchair Access Guide to the Oakland Berkeley Area,” Ken Stein Editor / Photographer, Access California, City Of Oakland, 1980.

Photo: © Ken Stein

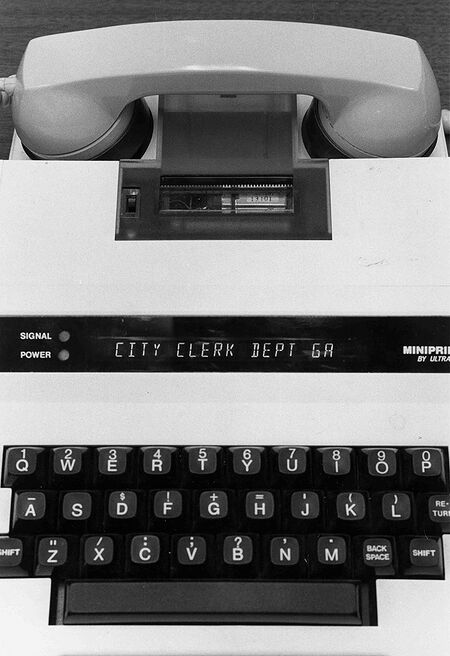

TTY machine for Deaf / hard of hearing telephone access. On screen: “City Clerk Dept GA (Go Ahead),” ca 1990.

Photo: © Ken Stein

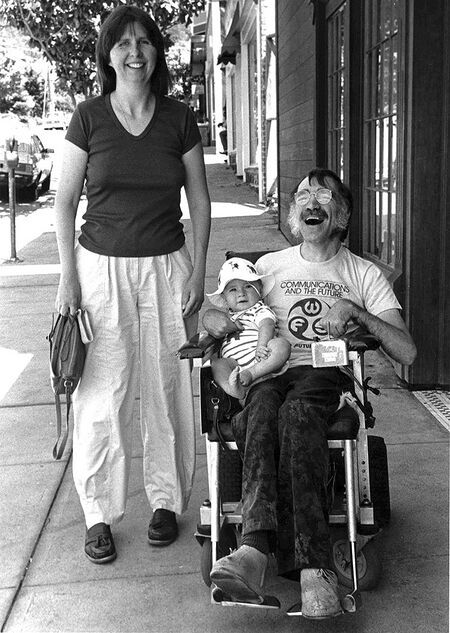

“The neighborhood [she or] he lives in”

Carole Krezman, Michael Williams and baby Malcolm, ca 1984.

Photo: © Ken Stein

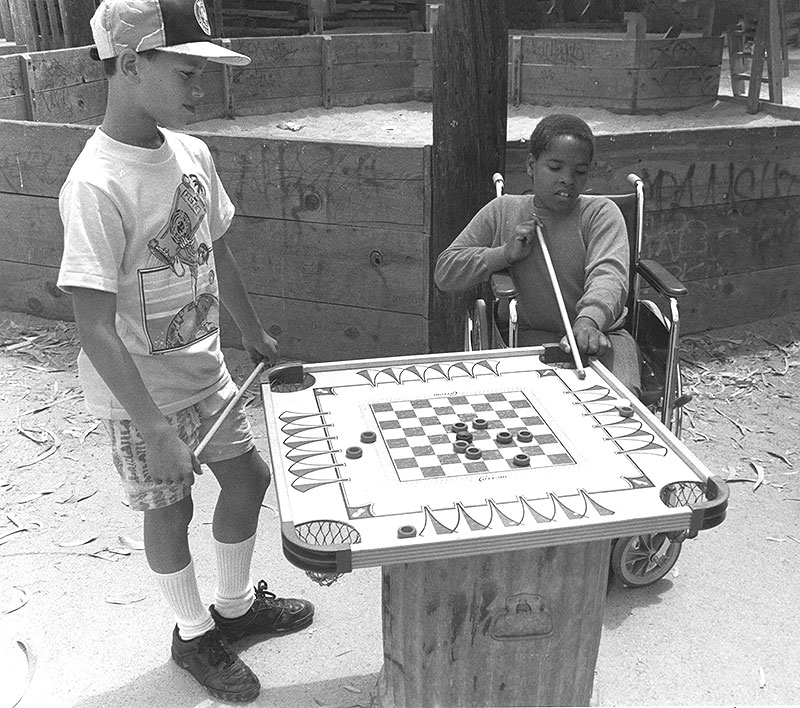

“The school or college [she or] he attends”

Two boys playing carems in the Franklin School playground, Franklin School. BUSD After-School Program, h/t Elaine Belkind.

Photo: © Ken Stein

Laney College, in “Let Your Fingers Do The Walking: An Access Guide To Public Facilities In The Oakland Berkeley Area,” Access California, City Of Oakland, 1981. Chapter heading page for Colleges and Universities, h/t Marilyn Golden.

Photo: © Ken Stein

“The factory, farm, or office where [she or] he works.”

Johnnie Lacy at the Berkeley Center for Independent Living, ca 1977.

Photo: © Ken Stein

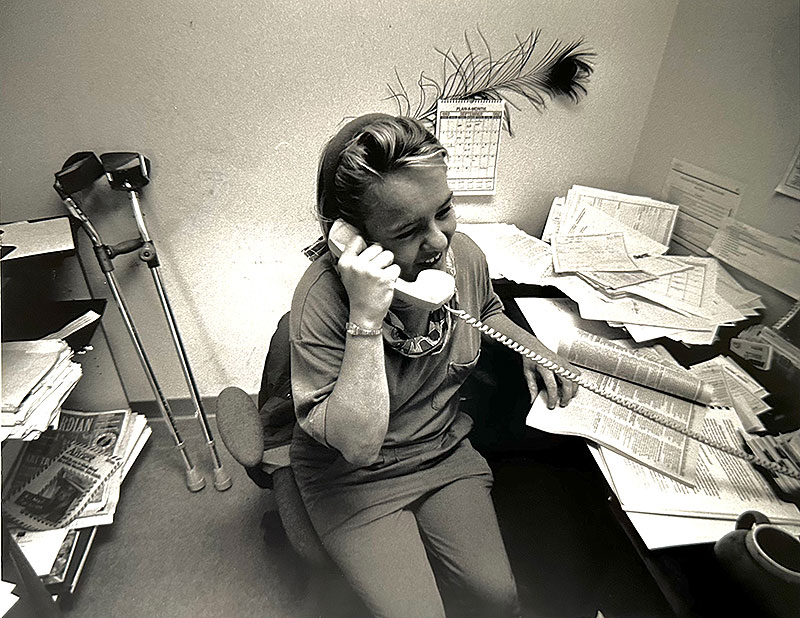

Maud Steyaert on her phone at the Pacific ADA Tech Center, 1990.

Photo: © Ken Stein

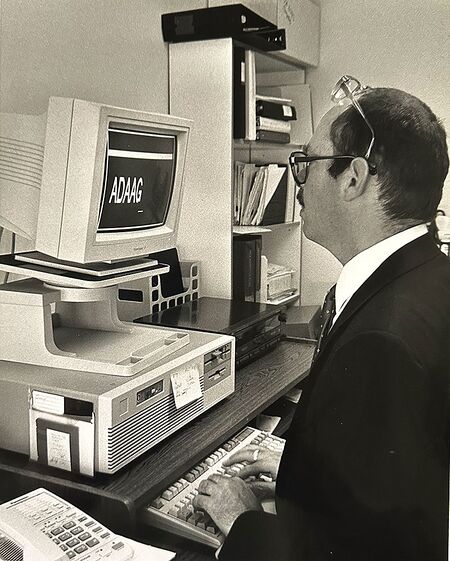

Guy Guber working on his computer / large print monitor at the Pacific ADA Tech Center, 1990.

Photo: © Ken Stein

“Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice”

Joyce Jackson at Disabled Peoples’ Civil Rights Day, October 20, 1979. Joyce is holding one side of a banner reading “Full Rights For Disabled People – Implement 504”

Photo: © Ken Stein

Judy Dadek and her daughter Emily in front of Berkeley City Hall. Berkeley Tenants Union pro-Rent Control Demonstration, ca 1980.

Photo: © Ken Stein

“Equal Opportunity”

City of Berkeley Recreation Department Summer Day Camp Program, 1983. H/t Elaine Belkind.

Photo: © Ken Stein

“Equal dignity without discrimination.”

Jerry Wolf at the UC Berkeley Art Museum looking at the huge wall-size painting of George Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth by Emanuel Leutze.

In “Let Your Fingers Do The Walking: An Access Guide To Public Facilities In The Oakland Berkeley Area,” Access California, City Of Oakland, 1981. The chapter heading page for Museums and Galleries.

Photo: © Ken Stein

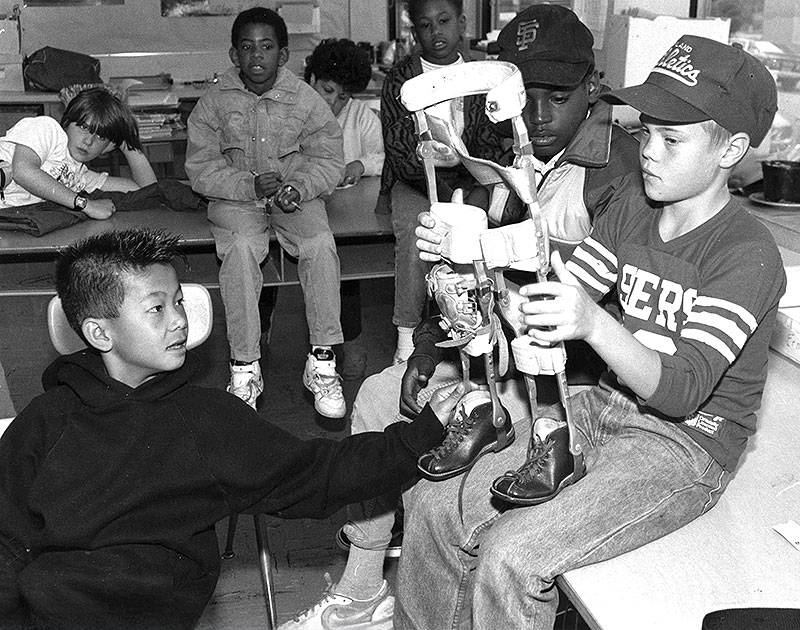

Two boys in a grammar school class examining an old fashioned pair of leg braces.

Photo: © Ken Stein

From the K.I.D.S. Project (Keys to Introducing Disabilities in the Schools). The K.I.D.S. Project taught disability awareness to primary school children, h/t Elaine Belkind.

“Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.”

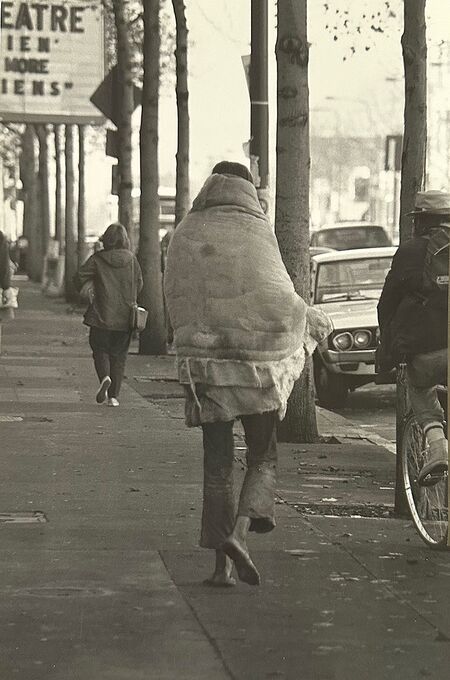

A homeless man (who had a severe psychiatric disability) walking down the sidewalk barefoot in the cold, with a dirty torn / stained blanket wrapped across his back. Berkeley CA, ca 1978.

Photo: © Ken Stein

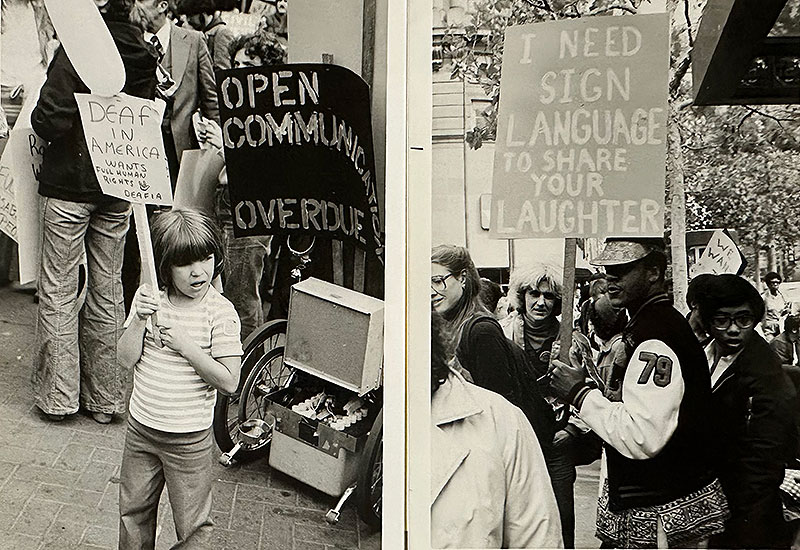

Deaf Demonstrators at Disabled Peoples’ Civil Rights Day, October 20, 1979. Picket signs reading “Deaf In America Wants Full Human Rights–DIA (Love ASL hand Sign)” “Open Communication Overdue,” and “I Need Sign Language To Share Your Laughter”

Photo: © Ken Stein

Remembering Disabled Peoples’ Civil Rights Day

“Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.”

- —Eleanor Roosevelt, speaking at the United Nations on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, March 27, 1958. United Nations,

Banner: “Disabled Kids Have Rights Too!!” Disabled Peoples’ Civil Rights Day March And Rally,” October 20, 1979.

Photo: © Ken Stein

Dale Dahl at the APTA (American Public Transit Association) Demonstration 1980, holding picket sign: Support 504.

Photo: © Ken Stein

Remembering Dale Dahl: A Decisive Moment, And The Gift Of History

Note: In the years after 504 was passed and before the ADA … The APTA demonstration was protesting the American Public Transit Association’s opposition to putting wheelchair lifts on public buses in their support of the “Cleveland Amendment.” They were holding their annual meeting inside the hotel. The Cleveland Amendment would have allowed local public transit providers to decide whether or not they wanted to make their busses accessible, or to provide an alternative / separate and unequal / “public option” service. The Cleveland amendment lost I believe by one vote.

Anti-Electroshock Demonstration, Herrick Hospital Berkeley, 1982.

Photo: © Ken Stein

In 1982, NAPA (the Network Against Psychiatric Assault) spearheaded a successful drive to ban electroconvulsive “shock” therapy in Berkeley. The ballot measure was passed by Berkeley voters in 1982, but was later overturned by the courts.

And remembering Leonard Frank ...

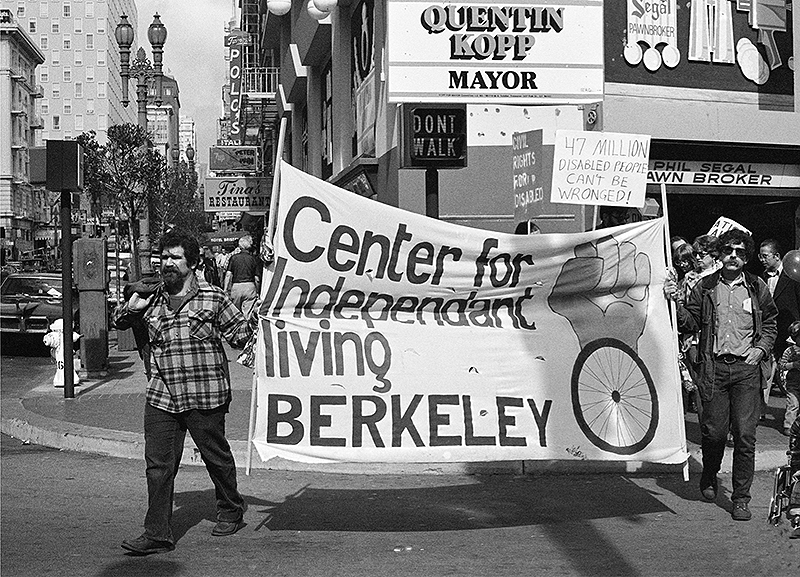

CIL employees Doug Brown and Gene Turitz holding the Center for Independent Living (CIL) Banner at Disabled Peoples' Civil Rights Day March and Rally, San Francisco, October 20, 1979. The Disabled Peoples' Civil Rights Day March and Rally was organized by CIL's Disability Law Resource Center (DLRC / later DREDF). It was held in response to continued non-implementation of Section 504 and a number of unfavorable court decisions, including the Davis decision by the Supreme Court.

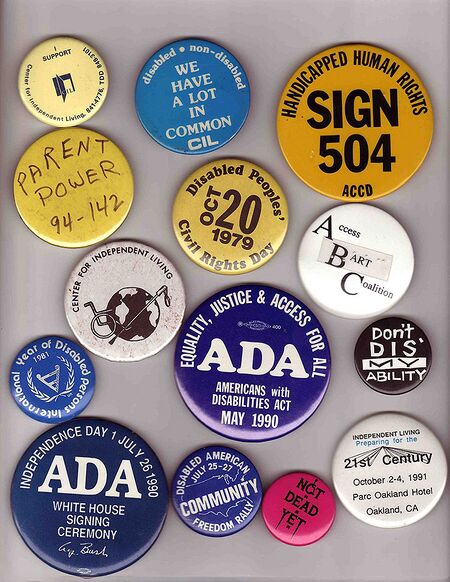

Disability Buttons Collection.

Photo: © Ken Stein

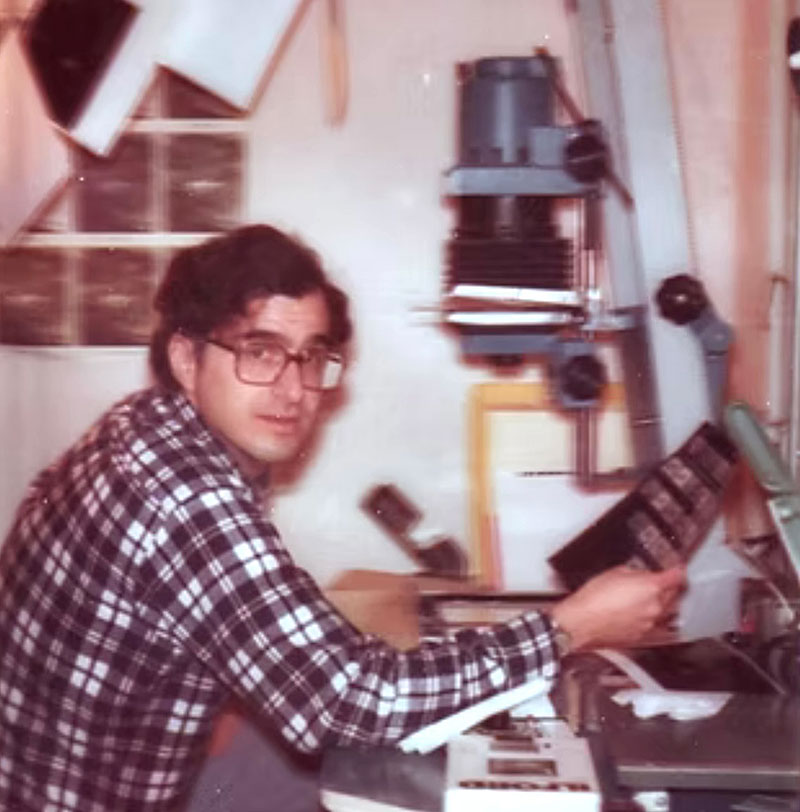

Me raising hell about rent control at a Berkeley City Council Meeting ca 1982.

Photo by Jane Scherr, Grassroots Newspaper.

At work in the Grassroots Newspaper darkroom, ca 1980.

Photo: © Ken Stein

A Brief History of the Bay Area Disability Rights Movement

Presentation by Ken Stein, Program Administrator, S.F. Mayor's Office on Disability, Mayor’s Disability Council Meeting, San Francisco City Hall, July 16, 2004.

Four or five years ago, I was working at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, some people from the World Institute on Disability and the Center for Independent Living and I did a series of classes for fifth and sixth graders in the Berkeley public schools about disability rights history, where they interviewed people and we talked about the movement and showed movies and so on. It was a great program.

I started out each of those classes reading this poem. And then later, when I would talk to smaller adult groups I would also start out with this poem. It's by a young girl who is about 10 or 11 years old who is from Poland. It's in a book entitled "Creative Expressions of Augmented Communication." Augmented communication means where people might use a message board or head stick or point with their eyes to type out things on some sort of gadget that gives voice output.

This poem is by Magdalena Raczkowska and it's called "The Different One In Society."

- "I do not like when people pity me.

- Like those ladies in the shops or people in the streets.

- They stare at me as if I were a weirdo.

- I really hate that look.

- I want people to accept me as I am.

- Sometimes I just want to stick my tongue out at them.

- But I never do.

- I think to myself, it's not worth it.

- Often, I ask myself the why don't people want to understand me.

- Isn't it so simple?"

And I like to start out with this poem because I think it expresses feelings that everyone can relate to. I think it points out also that disability is something that affects people of all ages, in all countries. Even though today, we're going to be talking about laws and movements and leaders and struggles, the poem points out that it's important to remember that ultimately, disability rights comes down to something very individual and very personal.

Why is disability rights history important?

History isn't only something that's happened. It's also something that's happening in the present. It's a truism that history really is our key to understanding the present. This is especially true in the arena of disability rights.

In spite of the passage of a number of disability civil rights laws over the past three decades, much of the public at large, including the media still operates philosophically and attitudinally on the centuries old medical and charity models of disability. At the time the 1963 Civil Rights Act was passed most Americans of all ethnic background got it. They'd seen Black demonstrators being beaten up and fire-hosed by the police in Montgomery and Birmingham. They had learned about racism and inequality, the murder of the freedom riders, understood it all, and have transmitted it down to new generations in the home, in media and the schools, in a civil rights context. For the most part, it's true that people today do not understand disability issues in a civil rights context.

Several years ago there was a movie called "Pay It Forward," where Haley Joel Osment, the boy who was in "The Sixth Sense," was given a homework assignment to do something to change the world.

Well, 30 years ago, I began working at an organization called the Center for Independent Living (CIL). I had no idea at that time that this was an organization that was literally going to change the world. It would change the way that people had thought about people with disabilities for centuries, and it would change the way that people with disabilities thought about themselves.

When I started working at CIL in 1974, there were 12 people working there in a small office on University Avenue. When I left 8 years later, there were 30 departments, over 100 employees, a million dollar annual budget, and it had become a model for what would eventually become currently over 400 independent living centers across the country, as well as a major international movement.

Throughout history, the biggest problem for people with disabilities, just like other minority groups, has been the stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination that they've faced.

I think those are ideas well expressed in the poem I read earlier.

However, in speaking about disability, we tend to use shorthand by referring to "attitudes." But to really understand disability rights, we need to get back to the basics.

A stereotype – A way of thinking about a person or group that follows a fixed common pattern, paying no attention to individual differences.

Prejudice – An opinion formed without knowing the facts, or by ignoring the facts, an unfair or unreasonable opinion. Unreasonable dislike or distrust of people or feeling uncomfortable around people just because they belong to a group that's different from one's own.

Discrimination – The practice of treating certain groups of people unfairly or unequally because of prejudice, as in discrimination against minority groups. The stereotypes that people have about a certain group results in prejudice and discrimination.

And what about civil rights?

Civil rights are laws that ensure the rights of all citizens (regardless of race, religion disability, or gender), to vote, to enjoy life, liberty, property, and equal protection under the law. That is, the right to not be treated differently than others just because of one's race or sex, or sexual orientation, or disability.

We take a lot for granted today, and a lot has changed for many of us since we were children. And we're talking about some very recent history. I think it's particularly surprising that in this land of "liberty and justice for all," it took over 190 years for a civil rights act to be passed and 215 years for a comparable law, the ADA (the Americans with Disabilities Act), to be passed for people with disabilities.

When I was growing up in the 1950s and '60s there were virtually no children with disabilities in schools. Many children with disabilities were either kept at home or sent to special schools or at most, were in segregated classes in public schools or in institutions. Housing wasn't accessible, people with what were regarded as having severe disabilities weren't expected to work, and even if they wanted to, nothing was accessible. Buildings weren't accessible, bathrooms weren't accessible, there were no curb cuts, offices where people worked weren't accessible. Millions of children with developmental, physical, and psychiatric disabilities were labeled, institutionalized and warehoused for their entire lives.

As the folk singer Carolyn Hestor sang about her own family, in the early 1960s:

- "My little sister Donna

- was sent to school today.

- They locked the door behind her

- and they threw the key away."

- And that's the way it was.

I grew up near Chicago, Illinois in a town called Skokie. I remember when we first moved there, there was a big golf club nearby, the Evanston Golf Club, which had a big wooden sign on the front gate, "RESTRICTED." That meant that they would let anybody in the public join, but they wouldn't let Blacks or Jews be members of that golf club. That would be against the law now but it wasn't then.

At that time there would be ads in newspapers about jobs for "women only" or "men only" and it wasn't against the law to pay women less than men were paid for the same job. There was a GI Bill that millions and millions of Americans reaped the benefits of after World War II, but Blacks were excluded from the benefits of that law, and were denied housing, maintaining a segregated society.

One thing that made a big impression on me at the time when I was young in Skokie, was that one time in the Skokie News there was an article about a woman who had taken her ten year old son who had cerebral palsy, to the miniature golf course in nearby Morton Grove. The manager told them they would have to leave because it would upset the other miniature golfers if they saw someone with a disability at the golf course. They would have to leave.

That would be against the law now, but it wasn't then. So what changed? Well, in large part, what happened was the 1960s.

Recently, I had the pleasure of re-viewing a movie called "Berkeley in the '60s," a documentary. And what I found most fascinating about that film was that the very first scene in that movie isn't in Berkeley at all, it's in this building – San Francisco City Hall. The House Un-American Activities Committee, HUAC, was holding hearings in the Supervisors' Chambers two floors below us. Well, what the movie showed was demonstrators being fire hosed by the San Francisco Police and Fire Department, being dragged down the steps, in the rotunda of this building.

Subsequent to that, the FBI made a promotional video about the communist danger in this country, and kids all over the country saw that and said, "Hey, that's where I want to be!"

And they came running to San Francisco and they came running to Berkeley. This is a demonstration put on by Berkeley students.

I know this seems kind of tangential, but really, there is a parallel between Berkeley in the 60's drawing young people from all over the country, and the national publicity about the local disability rights movement drawing people here with disabilities as well. And it's also more than that, because it's also true that to understand the disability rights movement of the '70s, we need to understand Berkeley in the '60s. There is a super direct connection.

What was going on during that time of course was that civil rights was a huge issue. Berkeley students, a number of them had been down South to register Black voters, they'd come back north, they were organizing, there were huge protests at the Sheraton Palace Hotel, and it was a huge victory for the civil rights movement when the Sheraton Palace Hotel agreed to hire black workers.

It was also a major threat to the status quo. The directors of the University didn't want these kids distributing literature on campus and the Free Speech Movement was essentially born. The Free Speech Movement was modeled on the African American civil rights movement, which had a huge overflow impact on the development of other movements to follow – the women's rights movements, the gay rights movement and as we're talking about today, the disability rights movement.

The reason I talked about all of that at some length is because in 1962, Ed Roberts started going to school at Cal. Ed Roberts was somebody who had a severe disability who lived for the most part in an iron lung. His Department of Rehabilitation (DR) counselor had told his mother there was no point in him being a client because he could never get a job. Well, as it turned out 15 years later, Ed was the Director of the Department of Rehabilitation, but at this time he was a student entering Cal.

And this was the newspaper article that accompanied his admission to the school. If we could have the document camera, please.

The article I believe is from the Berkeley gazette, December 5th, 1962. It shows Ed in a bed, and the headline reads, "Helpless Cripple Attends U.C. Classes Here in Wheelchair". Well, what were they going to do with somebody who was in an iron lung, in an inaccessible city? They put him in a hospital and he stayed at Cowell Hospital when he wasn't in classes, and it worked out really well, and he did very well at Cal.

In the second year they said, "Well, this seems to be working out OK . . . We'll let some other disabled students come here and they, too, can stay in the hospital." By 1967, there were 12 students with disabilities in what was now the Cowell Residence Program. And what was going on around them of course was that the campus was going nuts with the Free Speech Movement. Students were out on campus every day demanding no "In Loco Parentis," which means we don't want the university to be our parents. We're adults, living in a hospital, with nursing charts and dating patterns being recorded, and it was no way to live. And unfortunately, there were no options out in the community.

It was clear to all of them that they were not living independent lives, and they understood very well the barriers that were keeping them from living out in the community. Basically, they were living out the medical model in the very midst of all of this turmoil for freedom and self-determination.

In 1972, Ed Roberts discovered that there was some federal money that they might be able to use to set up a program. What they did was to set up U.C. Berkeley's Physically Disabled Students Program (PSDP). Later the name was changed to DSP, the Disabled Students Program. It would allow students with severe disabilities to live out in the community. It offered housing assistance, personal care assistance / attendant referral, benefits counseling, etc.

In the past, services for people with disabilities had been provided to people in a very fragmented manner. Go here for this, go there for that, and these services were provided by non-disabled professionals who didn't know or understand what people with disabilities really needed or wanted. Basically, they were running on attitudinal models that were based on very low expectations.

So this organization, the U.C. Physically Disabled Student Program, was set up and run by people with disabilities themselves. It provided a whole variety of services under one roof that would help people to live independently in the community. They also had a wheelchair repair department. Before the independent living movement, people with disabilities weren't expected to be out living in the community. Wheelchairs were made for being used in hospital corridors, so they'd always be breaking down because they weren't designed for sidewalk use. So "wheelchair repair" became very important and some people in the community began designing wheelchairs that worked a lot better.

PDSP was based on three basic principles:

- That those who know best the needs of people with disabilities and how to meet those needs, are people with disabilities themselves;

- That the needs of people with disabilities can be met most effectively by comprehensive programs that provide a variety of services under one roof; and that

- People with disabilities should be as integrated as possible, as fully as possible, into the community.

And it worked out great. In fact, it was the very first organization of its kind in the world, and it was very successful.

But because of funding it could only provide services for students, and it couldn't provide these services for people moving into the community. So they set up an organization called the Center for Independent Living which opened its doors in 1973. And just like PDSP, what it did was, it provided a variety, a wide variety of core services under one roof to enable people to live independently in the community.

They had attendant referral, housing assistance, wheelchair repair, van modification, orientation & mobility training, deaf services, blind services, job placement, etc. As I said earlier, even the idea of living independently was a new idea. By and large, people with disabilities were thought of as sick and helpless and pathetic, to be helped by charity and the goodness of people's hearts. People with disabilities weren't expected to live out in the community, to go to school like other kids, take buses, shop in stores, work.

I think it's worth pointing out that as one of the great early disability advocates, Judy Heumann once said, "Independent Living isn't doing everything by your self; it's being in control of how things are done."

Pretty soon, the idea spread and now there are over 400 independent living centers in the country.

It was very clear to the founders of the independent living movement that there was a lot more to be done than what they were doing. What good was it to live in the community if you were unable to get anywhere if there were no curb cuts, if transportation wasn't accessible? If schools weren't accessible? If people could discriminate against people with disabilities in getting jobs, and there were no laws against it?

So early on, the leaders of the disability movement worked to create laws that would ensure accessibility and civil rights. Early on, at CIL, a department called the Disability Law Resource Center was set up that later incorporated as the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF), which is the organization I worked at for ten years prior to coming to working for the City of San Francisco. DREDF has had a very proud role in the drafting, passage, and implementation of every major piece of disability civil rights legislation of the last 30 years.

As I mentioned earlier, the disability rights movement owes a huge debt to the Black civil rights movement. The disability rights leaders modeled their movement on the Black civil rights movement . . . working to get laws passed, having demonstrations, singing freedom songs, you name it.

And here we come to 504.

In 1973, Congress passed the Rehabilitation Act. There was a section of that law, Section 504, which is only a sentence or two long, and what it said was that any entity that receives any Federal money may not discriminate against people with disabilities. That included all public schools and universities and city and state governments. But by 1977, four years later, the rules that needed to be written to explain what that law meant, the Regulations, had never been issued and approved by the government. And so the law couldn't take effect.

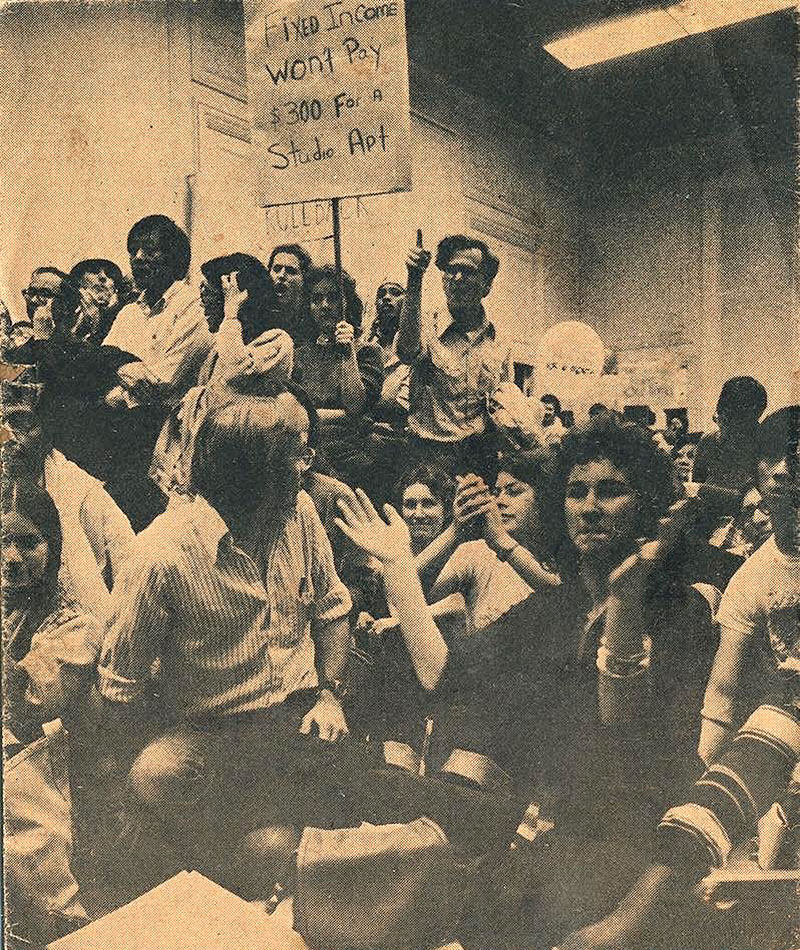

In April 1977, a lot of people with disabilities around the country organized demonstrations about that. The largest demonstration in the country was organized by leaders at the Berkeley Center for Independent Living. The demonstration was here at the San Francisco's Federal building, 50 United Nations Plaza, at the offices of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW).

The sit-in lasted for 28 days. Over 100 people sat in at that demonstration, and it still holds the record for the longest sit-in of any federal building in U.S. history. For the first time, a broad range of disability groups had joined together in coalition, as would also be the case with the ADA.

Also, now is a good time to point out of the important role of women in key leadership positions of the movement. There were people like Judy Heumann and Kitty Cone and Mary Lou Breslin, Cece Weeks, Debbie Kaplan, Diane Lipton, Arlene Mayerson, and Suzie Sygall, and many many more. And that's really something very different from other early rights movements. From the outset, women have held powerful leadership positions in the disability rights movement.

The 504 sit-in was successful. The demonstrators got the regulations signed that they wanted to get signed. And it's super-important that that happened, because what they got was a definition of disability that included physical and psychiatric disabilities, it included alcoholism and a history of drug abuse, and it did not allow for the provision of "separate but equal" as being okay, as the Carter administration had proposed. In opposition to the Carter administration, the demonstration resulted in all of those things being a part of the law. It's what people were sitting in for, for 28 days.

So why is this so important? —Why it's so important is because these 504 Regulations were the exact model, almost an identical overlay, for the Americans with Disabilities Act (the ADA) and its implementing regulations, which passed in 1990. The ADA made it against the law for private companies, including stores and restaurants, as well as city and state governments, and private employers, to discriminate against people with disabilities. So for the first time in our nation's history, people with disabilities were brought under the broad umbrella of the Civil Rights Act, which protected other groups.

I need to emphasize that I've only given a tiny piece of disability rights history. There were things going on before what happened in Berkeley and San Francisco, and there's a lot that's gone on since. In 1940, the National Federation for the Blind (NFB) organized on a national level to fight for their rights. It was the first time that people with a specific disability had done so. Decades later, NFB served as the model for other organizations of people with disabilities.

Jacobus Ten Broek, the first president of the National Federation for the Blind, once said, "Of course we cannot be required to love one another. But we can be prevented from expressing our hatred, our superstitions and our prejudices in terms of public law and social policy. We cannot require the sighted to embrace the blind as brothers, but we can stop them from placing obstacles in their path."

What the independent living movement has shown is that the greatest barrier to the integration of people with disabilities, lies not in the disability, but in the physical, attitudinal, and communication barriers that stand in their path. What the disability, independent living, and civil rights movement has done, has been to help knock down a lot of those barriers.

While a lot has changed, a lot remains the same. Today, just as was the case in the 1950s, as well as when 504 was passed, as well as when the ADA was passed, too many adults and young people with disabilities are being unnecessarily warehoused in institutions, and we still see too many media images showing people with disabilities as either being pitiable or else on the flip-side of that coin, inspirational. And there's still a lot that needs to be done.

Nonetheless, we have a lot to brag about. As was pointed out earlier, several years ago we celebrated the 20th anniversary of the 504 Demonstrations. We put on a party for over 600 people at the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, we served dinner and we showed a video history of the demonstration that we had produced, and we produced an hour-long radio documentary on the history of 504. We also used that opportunity to get video histories of people that were at the demonstrations. I was the Chair of that committee. We also put out a commemorative book, in which I wrote:

"Those of us who participated in the 504 sit-in, those of us who have shared in the growth and development of any of the multitude of independent living, disability access and disability rights organizations, those of us who have participated in and supported public policy development and advocacy, or who have demonstrated for the rights of persons with disabilities over the past three decades, all of us have reason to be proud and reason to celebrate. It is no exaggeration to say that we each have participated in and have been an integral part of one of the greatest and most successful people's movements of the 20th century."

The effort continues and we can all be proud to be a part of it. Thank you.

For the past half century Ken Stein has actively worked to further the cause of Independent Living, Disability Access, and Disability Rights. From 1971-73 he was an early staff member of Bonita House, Berkeley's first Halfway House for persons diagnosed with psychiatric disabilities; and before that was a volunteer at Napa State Mental Hospital. He began working at Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living in 1974, and was the Program Administrator at the City of S.F. Mayor's Office on Disability from 2002 until his ‘retirement’ in 2013. For the ten years prior, he was the Manager of the National U.S. Department of Justice ADA Information Hotline at DREDF (The Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund). Over the past six decades, Ken’s speaking, writing, photography, and collection of artifacts have greatly informed and given voice to the history of the Bay Area Disability Rights Movement.