Arab Immigration Patterns to San Francisco

Historical Essay

by Ahmed Sharaf, 2025

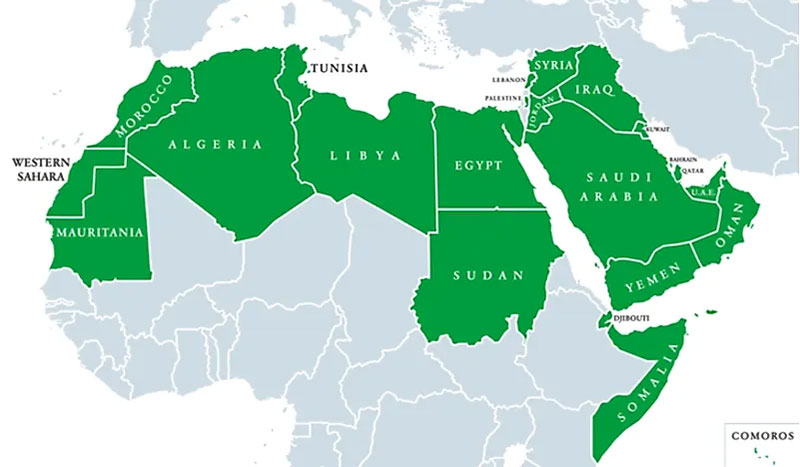

Arab speaking world, 2025.

Source: World Atlas

When you take a walk through the Tenderloin neighborhood, most probably you will hear Arabic conversations mixed with English, smell cardamom wafting from coffee shops, and see signs in Arabic script above halal butcher shops. This vibrant Arab community didn't appear overnight, it's the result of over 140 years of immigration, struggle, and community building. What began with a small group of Syrian and Lebanese peddlers in the late 1800s has now grown into a community of thousands. Their story shows how a small invisible minority became an integral part of the city's cultural fabric.

What defines an Arab?

An Arab is a person that has roots from the area encompassed by the 22 current Arab countries in the Middle East: Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoros Islands, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. The borders of these states have shifted throughout the years, but they are all united by history, culture, and most importantly one language: Arabic. (Arab American Development Center n.d.)

Early Arrivals (Late 1800s - Early 1900s)

Arab immigrants first came to America during the late 1800s when the Ottoman Empire was falling apart. U.S. immigration officials usually labeled them as "Syrians," even though most of them came from Mount Lebanon and some were just non-Syrian Christians who happened to speak Arabic. They left home to escape military conscription, religious conflicts, or simply for better economic opportunities. (Jones n.d.) (Little 2022)

San Francisco was not the first choice for Arabs to settle in the U.S. as cities like New York, Boston, and Detroit were more popular destinations. Their total number was pretty small compared to European and Asian immigration here. Fewer than 100,000 came to the entire United States before World War I. (Jones n.d.) Many of these early Arab immigrants became traveling salesmen, going from town to town selling linens, spices, and religious items. By 1900, most Arab immigrants in America worked as peddlers. Eventually some made their way to California by following railroad lines and trade routes.

In the early 1900s, a small tight-knit Arab community formed in San Francisco. They typically lived around South of Market and Downtown close to the port and train stations. According to Sam Mogannam—a second-generation Arab San Franciscan and a child of Bi-Rite store's founders—many of the early immigrants worked in the small businesses of their relatives or fellow Arabs, in convenience stores or at any other available jobs, until they were ready to afford their own shop or business. Some also had shops selling Oriental rugs or imported goods, or they operated coffeehouses, capitalizing on Americans' fascination with "exotic" products. They would work until they earned enough money to support welcoming other members of their families back home as well, then the cycle would repeat.

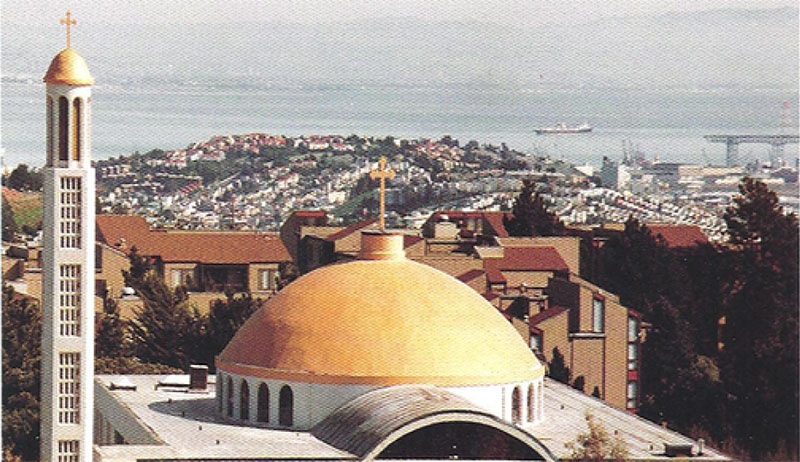

St. Nicholas Church.

Source: St. Nicholas Church

The 1906 earthquake disrupted everyone's lives, but by the 1910s the Arab community was stable enough to start building lasting institutions. In 1924, however, the U.S. passed immigration quotas that basically shut the door on Middle Eastern and most other immigration. For about forty years, from 1924 to 1965, Arab San Francisco grew very slowly, mostly through kids born to earlier immigrants. During this period however, there were some big milestones like Arab Christians establishing St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church in 1937, which was the first Arabic-speaking church in the city. By World War II, there were probably only a few hundred Arab Americans in the entire city. (Jones n.d.) (St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church n.d.)

New Waves After 1965

Everything changed in 1965 when Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which threw out the restrictive quotas. Almost immediately, new waves of Arab immigrants started arriving, and the community's size and diversity grew quickly. Many people came from countries going through serious turmoil. Palestinians fled after the Arab-Israeli wars, especially following the 1967 Six-Day War. Lebanese families escaped their country's civil war which lasted from 1975 to 1990. Egyptians came for graduate school or tech jobs. Iraqi refugees arrived in the 1990s, running from the Gulf War and Saddam Hussein's regime. (AAPIPMEC 2011)

San Francisco attracted many of these newcomers because of its reputation for activism and progressive politics. Arab students at local universities formed some of the first Arab student organizations in the country. Mogannam mentioned how the 1967 war was one of the factors which brought his family here from Ramallah, and that his father’s cousins were founding members of the Ramallah Club in San Francisco. The Ramallah Club brought together Palestinian Americans from the West Bank town of Ramallah and launched the annual Palestinian Cultural Day Festival in 1978. (Palestinian American Coalition Bay Area n.d.)

Bi-Rite Market on 18th Street between Guerrero and Dolores, 1960s.

Source: Bi-Rite Market

According to Mogannam, Arabs were scattered all over the place in San Francisco. There were groups of Arabs in multiple districts. However, the Tenderloin neighborhood was the main hub for Arab immigrants, especially Yemenis and Palestinians dating back to the 1960s. The Tenderloin had always been a landing spot for new immigrants because it had cheap residential hotels and was centrally located. Many immigrants from these countries had initially worked as farm laborers in California's Central Valley. (Kelley 1986) But some eventually moved to San Francisco looking for year-round jobs and a real urban community. Mogannam notes that the Tenderloin was a good starting point because it was full of corner stores and was easy to start one or find a fellow Arab that would let you work at their business. His dad and uncle, Ned and Jack Mogannam, worked in the Tenderloin for two years at their cousin’s shop before buying their own store in 1964 which they called Bi-Rite. The workload was sometimes huge. Sam remembers his dad and uncle working in their cousin’s shop from 8 am to 2 am and sometimes even continued to work from their car. Most new immigrants would try to secure as much money as possible in order to support their lives in San Francisco.

Yemeni Kebab Shop in Tenderloin.

Source: US Menu Guide

The 1980s also brought waves of refugees from war-torn parts of the Arab world. Lebanese civil war refugees, along with Iraqi refugees fleeing various conflicts, were resettled through U.S. refugee programs. (Migration Policy Institute n.d.) Many found affordable housing in the Tenderloin and South of Market neighborhoods. You could see the neighborhood changing: Alongside Vietnamese Pho restaurants, there were now Yemeni kebab houses and corner stores selling sambusas and Middle Eastern spices.

Building Community Institutions

Arab Community members leaders meeting to start the Arab Cultural Center.

Source: Arab Cultural and Community Center

As San Francisco's Arab population grew, community leaders realized they would need more formal organizations. In 1973, more than 60 Arab Americans from different backgrounds came together to create the Arab Cultural and Community Center. They bought a Victorian house near Twin Peaks and opened the Arab Cultural Center in October 1975. This was finally Arab San Franciscans own public space. (Arab Cultural and Community Center n.d.)

Masjid Darrussalam.

Source: Islam SF

Religion also has always been central to Arab immigrant life. On the Christian side, Arab churches multiplied with services for Lebanese and Palestinian congregants. However, the major developments happened in Islamic worship. In 1959, the city's small Muslim population established the Islamic Center of San Francisco in Bernal Heights, the first mosque in the Bay Area. (Bernal Heights Neighborhood Center n.d.) The Muslim population continued to grow after 1965, so they needed bigger facilities. The breakthrough came in 1991 when the community bought a building at 20 Jones Street in the Tenderloin and turned it into Masjid Darussalam, the largest mosque in San Francisco. (Islamic Society of San Francisco n.d.)

Islamic architecture-themed mural on the mosque's exterior wall.

Source: Frederic Larsen, 2003, SFGate

In 2003, local artists painted a massive 54-by-30-foot mural on the mosque's exterior wall showing Islamic architecture inspired by Spain's Alhambra. This was San Francisco's first official Arab-themed mural. (Vargas 2003)

Life in Today's Tenderloin, or "Little Arabia"

The Tenderloin today is considered the heart of Arab San Francisco. When you walk down Jones or Eddy Street you'll encounter Yemeni coffee shops where you’ll find cardamom smell filling the air, you’ll see Palestinian-owned falafel joints, and storefronts with Arabic signs for halal butcheries. The Tenderloin now has the largest Yemeni community in Northern California, but it's also home to Palestinians, Jordanians, Egyptians, Syrians, and Moroccans. San Francisco has also become a refuge for Arab LGBTQ individuals who can't live openly in their home countries.

First Eid celebration in Tenderloin, SF 2025.

Source: ABC News

Daily life revolves around connection, faith, and small businesses. The Elder Arab men love to gather at Yemeni coffeehouses, and sip spiced tea while discussing news from home. Women shop at Middle Eastern groceries and walk their kids home from Islamic schools. Arabic and English conversations blend with the smell of fresh pita bread in local restaurants. In 2025, the Tenderloin hosted San Francisco's first Eid Street Fair where they had a night market celebration with vendors selling homemade baklawa, grilled meats, and jewelry under strings of lights. (American Community Media 2025)

To keep the community flourishing and integrated with neighboring communities, second-generation Arab Americans are also trying to leave a mark by contributing to chains of coffee shops and restaurants. The growth of Sam Mogannam's Bi-Rite stores across San Francisco is a great example of a successful local community-minded business. (Bi-Rite Market n.d.) Phil Jaber is a Palestinian American that decided to turn his corner grocery store into the popular Philz Coffee chain. (Philz Coffee n.d.) Mokhtar Alkhanshali grew up in the Tenderloin and wanted to revive Yemen's coffee industry, so he got Yemeni beans into Blue Bottle Coffee where they sold for $16 a cup. (Eggers and Bassett 2018)

Conclusion

Today there are tens of thousands of Arab Americans in San Francisco. They're incredibly diverse, spanning different religions and economic backgrounds. What ties them together is shared heritage and the common experience of making a home in this ever-changing city.

The community has left its mark everywhere. There are Arabic churches and mosques, annual festivals, performances by Arab orchestras and folk-dance groups, and restaurants serving everything from Yemeni mandi to Palestinian musakhan that have won over San Franciscans' hearts.

The story isn't over. New conflicts continue to send immigrants and refugees to American shores, and some will choose San Francisco as home. The existing community stands ready to help newcomers just like earlier generations did.

Resources:

Mogannam, Sam. 2025. Interview by Ahmed Sharaf. June 2025.

Arab American Development Center. “Facts about Arabs and the Arab World.” ADC. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Asian American Pacific Islander Policy Multicultural Education Center. “AMEMSA Fact Sheet.” AAPIP, November 2011.

Bernal Heights Neighborhood Center. “How the Islamic Center of San Francisco Meets Modern Needs.” Bernal Connect. Accessed June 9, 2025. .

Bi-Rite Market. “Our History.” Bi-Rite Market. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Eggers, Dave, and Dave Bassett. “Dave Eggers’s ‘The Monk of Mokha’: Mokhtar Alkhanshali Reviving Yemen’s Coffee Industry.” Vanity Fair, January 2018.

Islamic Society of San Francisco. “About.” ISLAMSF. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Jones, J. Sydney. “Syrian Americans.” Countries and Their Cultures. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Kelley, Ron. “The Yemenis of the San Joaquin.” Middle East Research and Information Project, March/April 1986.

Little, Becky. “Arab Immigration to the United States: Timeline.” History, March 23, 2022. Last updated May 28, 2025.

Migration Policy Institute. “Middle Eastern and North African Immigrants in the United States.” Migration Policy Institute. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Palestinian American Coalition Bay Area. “About Us.” PAC-SF. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Philz Coffee. “Our Story.” Philz Coffee. Accessed June 9, 2025.

St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church. “History.” St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church. Accessed June 9, 2025.

Vargas, Jose Antonio. “Arabic Mural Brightens Tenderloin: Artwork Helps Local Community Feel Represented.” San Francisco Chronicle, November 15, 2003.

Arab Cultural and Community Center. “About.” ACCC. Accessed June 9, 2025.

American Community Media. “In the Heart of San Francisco, Yemeni Immigrants Reshape a Community.” American Community Media, May 2025.