The Great Bicycle Protest of 1896

Historical Essay

by Hank Chapot

ED. NOTE: The 1890s popular movement for Good Roads, pushed most ardently by bicyclists, is of note for several reasons. Primarily the fight for better conditions for bicycling unknowingly set the stage for the rise of the private automobile. Within a decade of the big demonstrations detailed here, better roads and improved tire technology combined with breakthroughs in internal combustion to launch the car industry. Obviously the private automobile has played a pivotal role in transferring the cost of transportation to the individual (thereby intensifying financial needs, summed up in the absurd conundrum of “driving to work to make money to pay for my car to drive to work”). It has also been central to the speeding up of daily life, especially in the sprawl of the post-World War II era. (Of course if you’re stuck in a traffic jam during every commute, you may question how “speeded up” the car has made your life.) In any case, the colorful popular demonstrations that filled San Francisco’s decrepit streets in the 1890s find a contemporary echo in the monthly Critical Mass bike rides that started in San Francisco in 1992 and spread across the world. The unintended consequences of the 19th century popular mobilization for Good Roads provide important food for thought as we engage in political movements of resistance and imagination.

—C.C.

In the last decades of the 1800s, the bicycle became an object of pleasure and symbol of progress to Americans. Enthusiasts hailed it as “a democratizing force for good, the silent steed of steel, the modern horse.” The Gilded Age was the Bicycle Age. Millions of new bicyclists demanded good roads to accompany their embrace of this newfound means of transportation.

San Francisco, though third wealthiest city in the nation, was an aging boomtown. Streets were muddy, cobbled, unpaved and increasingly crisscrossed with streetcar tracks and cable slots—an unpredictable, hazardous riding surface. The city’s old dirt roads and cobblestone thoroughfares, originally laid for a village of 40,000, now served a metropolis of 360,000.

On Saturday night, July 25th of 1896, after months of organizing by cyclists and good roads advocates, residents cycled the streets in San Francisco, inspired by the possibilities of the bicycle.

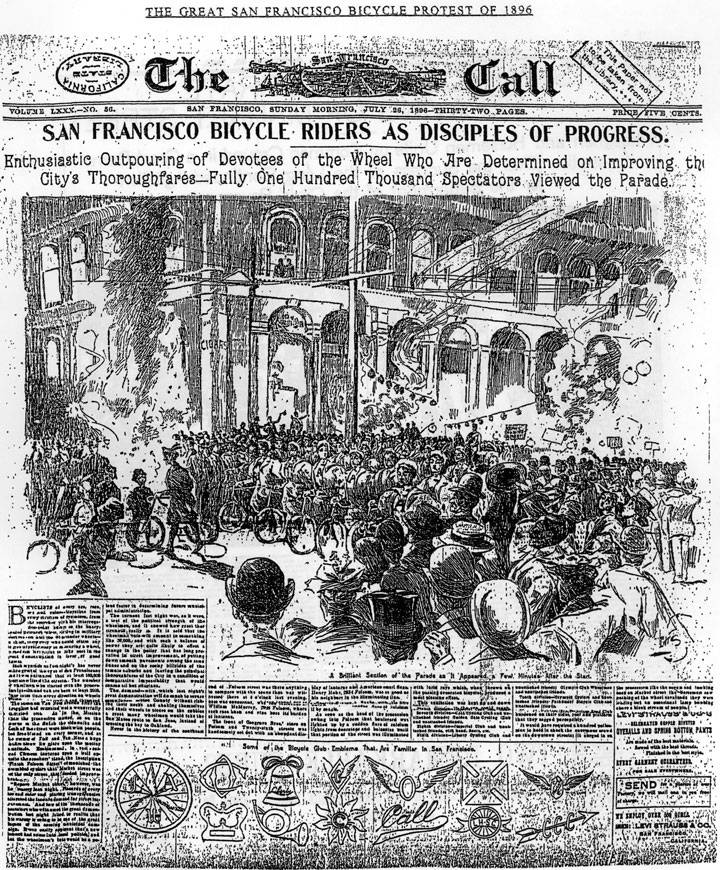

Enjoyed by perhaps 100,000 spectators, the parade ended in unanimous resolutions in favor of good roads and a near riot at Kearny and Market. The next day’s headlines in the S. F. Call captured the rally’s success: “A Most Novel And Magnificent Wheel Pageant Did Light Up Folsom Street” and “San Francisco Bicycle Riders—Disciples Of Progress.”

Since the 1880’s, riders across the country agitated for access and safer urban streets. Increasingly organized, their mission was political and social as cycling became a way of life. Bicyclists demonstrated in large American cities like Chicago, where wheelmen and wheelwomen held riding exhibitions and mass meetings, eventually forcing the city to withdraw a rail franchise for a West End boulevard.

The bicycle’s popularity exploded with the Safety Bicycle in 1885 which eliminated the danger of riding the giant “high wheelers.” The invention of the pneumatic tire in 1889 cushioned the ride. Bicycle ownership exploded in the 1890’s among all classes, shop owners purchased delivery bikes and businesses purchased fleets. Riders worked in organized “wheel clubs” that in addition to political activism, promoted social events, elected officers, ran competitions, sponsored dances and country rides. Many had clubhouses in the city and ran “wheel hotels” in the countryside. The women of the Falcon Cycling Club ran one in an abandoned streetcar near Ocean Beach.

Through the League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W.), founded in 1880 in Rhode Island, cyclists across the country joined the movement. Bicycle organizing was already in full swing by 1887 when the New York Times editorialized “. . . since bicycles have been declared vehicles by the courts, they should be declared by statute entitled to the privileges and subject to the duties of wheeled traffic.” As local agitation grew into a national clamor, the L.A.W. became the umbrella organization for the wider good roads movement. Bicycle agitation spread globally and locally. Candidates for local office found that unless they supported good roads, they stood little chance against well-organized L.A.W. chapters.

The San Francisco Movement

The 1896 protest was tied to the campaign to pass a City Charter that nullified unused street rail franchises. The charter was a core project of the Southside Merchants Association and the cyclery owners of the Cycle Board of Trade were unanimous in support. The protest offered a chance to rally San Francisco to the cause.

Cyclists risked crashing upon the raised steel slot in the roadbed through which cable cars gripped the cable, or slipping on the unpaved trackways. Most cyclists hated “the slot” and the street railways that ran upon it. Companies were killing old franchises to maintain their monopolies but leaving the tracks in place while more and more Mission District bicyclists needed access to downtown. They wanted abandoned rail tracks removed, pavement between the rails and reduction of the height of the slot, Market Street sidewalks reduced and overhead wires put underground when streets were rebuilt—common practices in eastern cities. They also wanted a road from their neighborhood to Golden Gate Park, and because thousands were riding there at night, they wanted illumination with electric lights like Central Park.

Meeting at the Indiana Bicycle Company Thursday before the parade, cyclists discussed their greatest opponent, the Market Street Railway, whom they blamed for the sorry condition of their main thoroughfare. “A person takes his life into his own hands when he rides on that street” someone said, accusing the streetcar company of sprinkling the street when many wheelmen and women were heading home from work. Another predicted that “with good roads, urban workers would ride to their places of business ...a good thing because it would cut into the income of the tyrannical street railroad.” They had a friend in the Street Department, a wheelman himself, who promised that all obstacles would be removed from the route Saturday and streets would not be sprinkled.

Folsom Street was the main boulevard through the Mission and cyclists worked diligently for pavement from 29th to Rincon Hill. The July 25th rally would celebrate the opening of a new portion. The Call interviewed owners and managers of some of the numerous cyclerys in town, who spoke as one. Each was a sponsor of “the agitation” and each would close early on Saturday. In San Francisco that July, their demand was “Repave Market Street,” their motto, “Where There Is a Wheel, There Is a Way.”

A five-year wheelman named McGuire, speaking for the South Side Improvement Club stated: “The purpose for the march is three-fold; to show our strength, to celebrate the paving of Folsom Street and to protest against the conditions of San Francisco pavement in general and of Market Street in particular. If the Press of this city decides that Market Street must be repaved, it will be done in a year.” Asked if southsiders were offended that the grandstand would be north of Market, McGuire exclaimed, “Offended! No! We want the north side to be waked up. We south of Market folks are lively enough, but you people over the line are deader than Pharaoh!”

The Emporium Department Store paved Market Street at 5th at its own expense, using tarred wooden blocks laid over the old basalt as an example of what Market Street should look like. Unfortunately, much of the Emporium’s efforts would be undone during the commotion later on Saturday evening.

Several politicians had been invited and most sent letters assuring their friendly disposition toward the wheelmen. With the appointment of so many vice-presidents to the parade committee including the Mayor, two Congressmen, both Senators and the City Supervisors, political notice seemed assured. From the Cycle Board of Trade and the Southside Improvement Association, the call went out to bicyclists and “all progressive and public-spirited citizens to participate.”

The Great Bicycle Demonstration July 25, 1896

Thousands of spectators from “the less progressive sections of the city” were expected. The decorations committee had distributed 8,000 Chinese lanterns. Citizens along the route were invited to decorate their properties, cyclists encouraged to decorate their wheels, with prizes offered for the finest displays.

By early evening, homes and businesses along Folsom Street were ablaze with firelight as the committee made its rounds. Businesses decorated their storefronts; one with colorful bunting and flags surrounded by lanterns, while a homeowner used carriage lanterns to cast colored lights onto the street. The Folsom Street Stables were a mass of torchlight.

Promoters had wished to get electric lights strung the length of Folsom Street, but the mansions, businesses and walk-ups “were not content to burn a single hallway light as usual but were illuminated basement to garret, a full stream of gaslight in every room commending a view of the street, with an abundance of Chinese lanterns strung from eaves to buildings across the street.” Calcium lights cast the brightest glow but many windows “were lit in the old fashioned style, rows of candles placed one above the other.” Every window was full of cheering spectators.

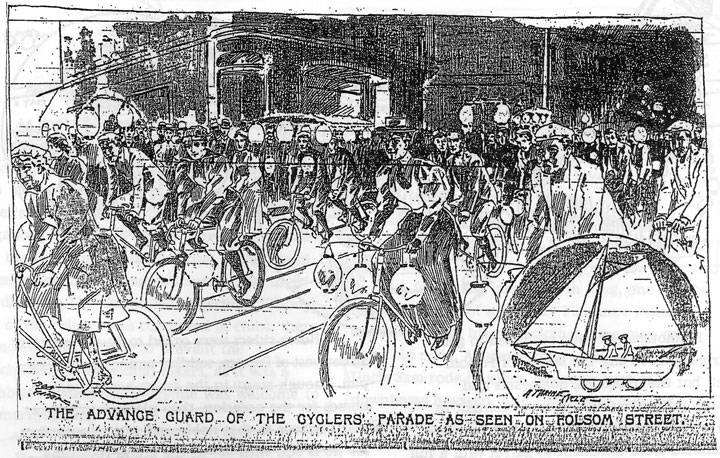

The divisions gathered on Shotwell Street in their finest riding attire and street clothes or their most gruesome costumes. The largest (from the L.A.W.) dressed as street-laborers. The Bay City Wheelmen, YMCA Cyclers, the Pacific, Liberty, Olympia, Call and Pathfinders bike clubs were all represented. Members wore insignias of their affiliations. “Unattached friends” were invited to join a favorite division.

Bicycles were adorned with ribbons and painted canvas with lanterns strung from the handlebars or from poles above—creating “a sea of Chinese lanterns as far as the eye could see.” One was decorated with a stack of parasols, another intertwined with flowers and garlands, others “revolving discs of light guided by mystic men in garbs of flame.” A few rode the old-fashioned “high-wheelers.” Tandems were joined to create a pirate ship, another pair carried “a little chariot from which a child drove through the air two beautiful little bicycles.” Many carried cowbells that “turned the night into pandemonium.”

Clubs from as far away as Fremont, Vallejo, Santa Rosa and San Jose lined up alongside worker’s divisions, letter carriers, soldiers from the Presidio and sailors from Angel Island. The SF Call stated cheerfully, “Though most of the column was composed of clubs, there was no restraining line to prevent the participation of individuals. Everyone was welcome to the merrymaking.”

A few men rode in drag, one “in the togs of a Midway Plaisance maiden,” another as an old maid beside a young woman as the “Tough Girl.” Uncle Sam rode in bloomers next to a downhome hayseed. There were meaner stereotypes: Sitting Bull and Pocahontas, a man in bloomers mocking “the new women,” one in blackface, one “imitating a Chinese in silks.”

One riding club did not attend. For three years, the Colored Cycle Club of Oakland had sought membership in the League. Three days earlier they were again denied. But the Sunday Call would exclaim, “Bicyclists of every age, race, sex and color—bicyclists from every stratum of cycledom, the scorcher to the hoary-headed patriarch . . . turned out for the great demonstration in favor of good streets.”

The parade president had invited liverymen and teamsters to join the march, and though many southsiders had to rent horses, they planned to “pay a silent tribute” later at the reviewing stand near City Hall, “to that noble and patient animal, for he is still with us.”

The Parade Begins

Late in starting, the Grand Marshall “hid his blushes in the folds of a huge sash of yellow silk” and called the march. Orders had been passed down that candles not be lighted until commanded, but the streets were ablaze as the horsemen began. As the order to march came down the line, the glowing lanterns began to bob and weave above the crowds. Fireworks filled the air and the new pavement hummed beneath the wheels.

The children’s division proceeded with the Alpha Ladies’ Cycling Club in their first public ride. It had taken some effort to induce the Alphas to attend, yet the women’s clubs were greeted with heavy enthusiasm. The procession quickly stretched ten blocks in “literally a sea of humanity.” The children and a few others dropped out at 8th Street, but the majority of cyclists pressed on, all the while “good-naturedly” bombarded by Roman candles.

By 8th Street, the cyclists were forced to dismount and push their wheels through a narrow strip above the rail tracks as the police began to worry about the “over-enthusiastic crowds.” Upwards of 100,000 San Franciscans “watched the energetic wheelmen speed upon their whirling way.” The disturbance caused by the streetcars and the narrowness of the space available in the center of the street began to separate the bicycle divisions.

At Market, streetcars were “so burdened, their sides, roof and platform sagged perceptively.” The crowd filled the street and only a few lanterns appeared above the spectators. Riders had planned to dismount and push for three blocks to show “the pavement is too bad for any self-respecting wheel to use,” but ended up pushing much of the way. Approaching Powell and Market, “the cyclists encountered a surging mass.” Bells of a dozen trapped streetcars added to the chaos. When a number 21 car got too close to one division, some in the crowd began rocking it, attempting to overturn it.

Not surprisingly, some in the crowd had destructive intent, including, “an army of small boys from the Mission who ruthlessly smashed and stole the lanterns.” The Chronicle decried, “They stole them by the score and those they couldn’t pluck they smashed with sticks . . . others filled respectable spectators with dismay by their language.” Before the last cyclists had passed up Market Street a larger disturbance broke out among the spectators. “The hoodlums began a warfare upon the streetcars,” gasped the Chronicle. People were pulling up the Emporium’s tarred blocks and throwing them beneath the streetcar wheels and at the cars directly, breaking windows while passengers cowered inside. When a car stopped, they attempted to overturn it by rocking it and when one got away, they fell upon the next. Squads of police chased and clubbed the crowds back uptown.

At City Hall, both sides of Van Ness were “black with people,” when the lead firewagon finally appeared, well after 9:30 p.m., greeted by a great roar. At the grandstand in the gathering fog, accompanied by bursting fireworks, the crowd cheered as each new division straggled in.

On the reviewing stand sat many important San Franciscans; a Senator, a Congressmen, several Supervisors and the fine ladies and gentlemen of San Francisco’s southside community. A gigantic bonfire blazed in City Hall Square, another burned at Fell and Van Ness; fires glowed around the plaza. Behind the stage hung a huge banner lighted by the ubiquitous lanterns stating simply, “FINISH FOLSOM STREET.” Under a festoon of lights, speeches of “varying qualities of oratory” received tremendous applause.

Julius Kahn, an enthusiastic wheelman, preached good roads and great civilizations. Senator Perkins promised pavement to the Park, and lighting too. The last speaker claimed the bicycle had solved the age-old question that perplexed both Plato and Mayor Sutro, who rarely left the Heights in the evening: “How to get around in the world!”

Aftermath

Although the disturbance at Kearny and Market was not completely out of character for San Franciscans, the cyclists, to say the least, were not amused. Meeting Sunday after the parade, argument raged. Someone shouted “Chief Crowley is dissembling when he declares he could not put enough men out for a bicycle parade,” Mr.Wynne agreed. “They are perfectly able to be out in force around boxing night at the Pavilion when some ‘plug-uglies’ are engaged in battering each other.”

The final resolution declaring victory was approved unanimously.

“The parade exceeded any similar events held west of Chicago and the objects of the demonstration have been fully accomplished and we have aroused the sympathy and secured the support of the well-wishers of San Francisco.”

They decried the inefficiency of the Police Department and especially condemned the Market Street Railroad Company’s “outrageous, high-handed actions in operating and insolently intruding their cars into the ride, thus breaking into the route and materially interfering with its success.” A vote of thanks was extended to the Street Department for the fine manner in which it had prepared the road.

The Sunday papers estimated five thousand riders had taken part. The Examiner was effusive: “It was the greatest night the southsiders have had since the first plank road was laid from the city gardens into the chaparral and sand dunes where 16th Street now stretches it’s broad road.” The Call heralded “An Enthusiastic Outpouring of Devotees of The Wheel.”

That Sunday morning, the Examiner sent a reporter to Golden Gate Park to count cyclists, who had exclusive use of the drives. He recorded the number of women and men, types of wheels and clothing styles. “The men riding in the early morning, erect and never exceeding six miles per hour, wore knickerbockers, sack coats and scotch caps.” These were “the best type of cyclist.” Later, “the hard riding element appeared with a perceptible change in attire, their speed increased.” The clubs followed and finally those on rented wheels, their garb “apparently hastily improvised.” He observed numerous tandems. “Bloomer maids outnumbered their sisters in skirts 4 to 1.” The paper published hourly figures totaling 2,951 cyclists between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m.”

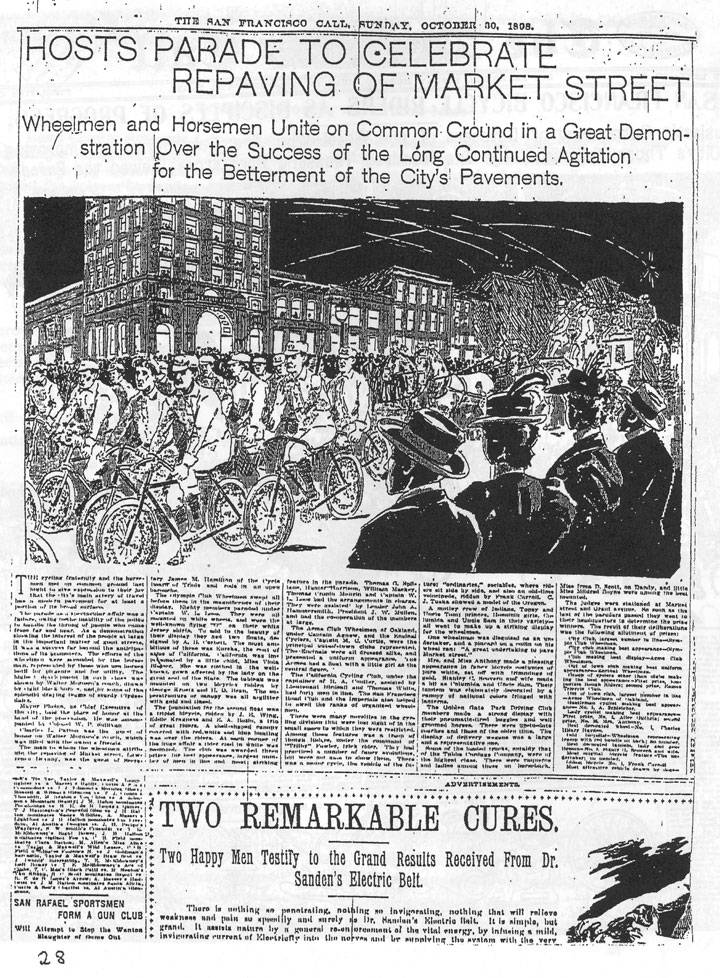

Great change took place, and swiftly. Cyclists rode in victory on a paved Market Street in 1898, but the victory was short lived. Roads were improved at about the time the bicycle lost public fascination to the automobile, and oil began to power transportation. Membership in the L.A.W. slipped heavily by the turn of the century. National bicycle sales dropped from 1.2 million in 1899 to 160,000 in 1909.

The bicycle remained an important option for workers and businesses for decades before being redefined as a child’s toy following World War II. Its popularity rebounded in the 1930’s and again strongly in the 1990’s. In much of the world, it never left. Appearing between the horse and the automobile, the bicycle had helped define the Victorian era and aided the liberation of workers, women and children, as it changed concepts of personal freedom. On two wheels, individuals were free to move across distances at a greater speed than ever before, independent of horse or rail.

The Great Protest of 1896 remained unique for 101 years until, on another July 25th, in 1997, bicyclists again took over Market Street, this time as Critical Mass—in direct lineage from the wheelmen and wheelwomen of 1896!