THE BURNING OF THE OLD STATE BUILDING

"I was there..."

by Kwazee Wabbitt, a.k.a. Michael Botkin

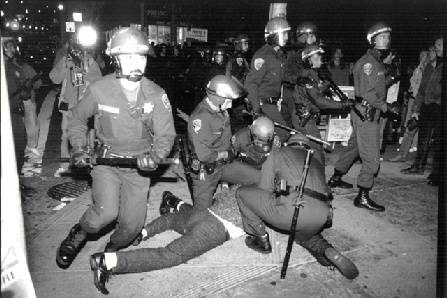

Scene from the Castro Sweep Police Riot of October 6, 1989 with police arresting Gilbert Criswell at the corner of Castro and 18th Streets.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

<flashmp3>http://www.archive.org/download/StateBuilding1991RiotSounds/RIOT1091.mp3</flashmp3>

Sounds from the streets during the protest.

FROM ONE WHO WAS THERE: In early October of 1991 the gay community was simmering with anticipation. The state senate had passed the long-contested gay rights bill, AB101, by just one vote. While running for office the year before, Governor Pete Wilson had specifically promised to sign the bill when it came to his desk. Now he was hesitating, weighing the potential cost to his presidential aspirations. It was also the anniversary of the "Castro Street Sweep," a random cop rampage that had sent several innocent bystanders to the hospital. The honchos who ordered it got off with slaps on the wrist just a few days before the actual anniversary, October 6.

On the ninth we heard that "Sneaky Pete" had vetoed the bill, and that a demonstration had been called downtown. We took the J Church to downtown, because I remember striding up North from Market Street on Polk, past City Hall and its empty park seeking the action. It was late in the day, just getting dark. At McAllister we paused. To our left, about a block away, was a large crowd massed around the steps of the brand new State building on Van Ness; beyond them were legions of cops in riot gear, defending it.

Streaming down McAllister to our right was a growing swarm of several hundred Queers. Members of Queer Nation, a kind of secular ACT-UP post-script, was at its peak at this time, and I recognized many friends from the Queer and street activist crowds, plus a few dark-garbed autonomen types. The main crowd looked less militant: "democratic" clubs and sectarians with banners and bullhorns listening to speeches. Without hesitating we joined the Queers, and I rushed about asking people what had happened, what was going to happen. "To the Old State Building!" was the only comprehensible statement I could get. This made sense: it was part of Sneaky Pete's dominion and the flashier new State building was clearly impregnable for the present. The mob skirted north on Polk en route to the building's main entrance on Golden Gate Avenue.

Indeed, Old State turned out to be defended only by about a dozen cops in standard uniforms, not wearing helmets nor wielding riot batons. The crowd of several hundred gathered in front of building's main entrance, pushing the cops into a frightened half circle in front of it. I climbed a tree across the street from this, where I had a good view. Others began grabbing construction materials, conveniently at hand in neat piles in front of the Federal building, and using them as weapons. Bricks broke windows; 10-foot two-by-fours were used to smash them further, and awkwardly propped up to serve as ladders, with limited success.

The cops remained trapped by the crowd, which was chanting stuff like 'gay rights or gay riots!' and hurling rocks at them. The cops unstacked some metal police barriers, deployed them around the entrance, and edged away from it, leaving only a couple of officers inside. The top honcho was frantically yelling in his walkie-talkie, but there was no sign of reinforcements. Here were no speeches and no bullhorns, only a milling, angry crowd, scenting retreat and fear. The barriers were swept up and wielded as battering rams!

They made short work of entrance and the cops retreated within the building. They were not directly pursued, but some people now used the barriers as ladders to get in through the broken windows. I could see them running about inside from my arboreal vantage, could see flames beginning to lick up from northwest corner of the building.

"Burn, baby, burn!" I yell. My voice carries well above the crowd. I chant it over and over, rhythmically, until some of the crowd picks it up. The cops are silent about 50 yards east on Golden Gate, just watching. Several hundred of us remained gathered between the entrance and the burning corner, somewhat bewildered by our success and wondering what to do next, how far to push it. The flames licked higher, and incendiaries vacated the premises; it looked like the fire was really beginning to catch and reach serious proportions.

Suddenly a pair of fire trucks appeared behind the clot of cops, and several phalanxes of blue-coated riot cops formed up in ranks on Polk. A high honcho stepped out in front with a bullhorn and began to do a formal "this is a restricted area, anyone remaining will be arrested" statement. I was amazed. Such courtesies hadn't been observed at the Oct. 6 "Sweep" (Nor would they be, a few months later, during the Rodney King riots). Our retreat was still open to the south, if we wanted to take it. It certainly looked like the cops were going to allow it in the interest of getting the fire trucks up fast. No one said a word, nobody pulled any "going limp' CD crap; if we could set fire to the Old State Building AND get off scott free, so much the better. We began to deliberately withdraw and disperse.

I lingered at the very tail of the crowd, trying to stay in the growing neutral zone between the cops and the rioters, trying hard to give off "I'm a neutral journalist" vibe. My black leather jacket and my boyfriend dragging me away by it defeated that pose. But we recognized a few friends from Street Patrol, also loitering at the rear of the retreat. All of us whipped out our distinctive lavender berets and put them on, and formed a line between the retreating crowd and the advancing cops.

(Street Patrol was an anti-bashing group that patrolled the Castro on weekend evenings. It was at its peak around that time, with about two dozen members and 8 person patrols. We wore bright fuschia berets and were well known in the gay community and to the cops; some said we had gang, or at least Guardian Angel overtones, and I suppose there was something to that.) The colorful hats (plus the fact that we all wore black leather jackets) and our facility with collective action made us a clearly recognizable barrier between the opposing masses. Half of us faced forward, half backwards, to make our action all the more ambiguous: were we taking responsibility for pushing away the crowd, and defending the cops, or the opposite? The crowd was rabbit-quick to disperse, the cops, tortoise-slow to pursue. In five minutes we were back on Market Street; the cops had halted a block away and the crowd had completely evaporated. We walked back, exhausted, elated, towards the Castro.

There had been absolutely no arrests, and not a drop of blood spilled on either side. I considered it an important victory for the community, a reaffirmation of the potency of the Queer Riot, and the legacy of the Stonewall and White Night riots. Some guilty liberals lamented the shattering of a specially commissioned multi-cultural stained-glass window over the building's entrance; others bemoaned that the burned-out office contained workman's comp. claims. Gay stream opinion, usually hostile to direct action, was smugly supportive of the riot and the rioters, however. I had a glow that lasted for days.

The glow definitely faded when I heard that several arrests had been made, weeks after the action, by identifying activists from tapes taken by a TV camera. I'd seen the camera at the actions but hadn't thought to impede its view or ability to record it; next time, folks, keep such things in mind. If the media can't keep from turning stoolie, they're not really "neutral" nor deserving of non-combatant status, are they?

In an ironic twist, the activists were identified by two openly gay cops who acquired this information by attending a Queer Nation meeting. They'd claimed they were there on their own time, and there were no rules to exclude them; QN was a pure consensus organization, which meant that even one or two people could block a motion. The cops were allowed to attend a couple of meetings, and a majority of the old cadre stopped coming to meetings. It was one of the final nails in the coffin for a group that was already on its last legs.

It was a very tight election year, and most of the charges were dropped. But several people had to do community service. But that Old State Building fire burns bright in my memory, a reminder of how quickly things can catch.

A line of motorcycle cops of flanked a march from the Federal Building in Civic Center to the Castro on October 6, 1989

Photo: Rick Gerharter

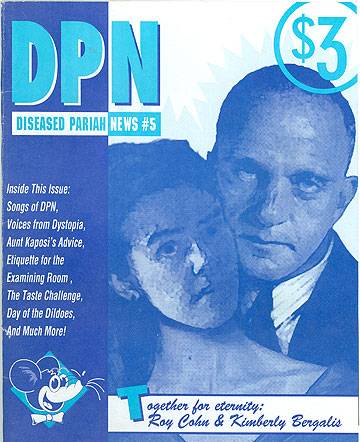

Michael Botkin, author of this short account, was co-editor of DPN ("Diseased Pariah News") for several years before he died in the early 1990s. DPN was a no-holds-barred journal of ribald and black humor by and for those with AIDS before the arrival of the cocktail that made it possible to live for years after testing positive for the HIV virus.