San Bruno Mountain

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

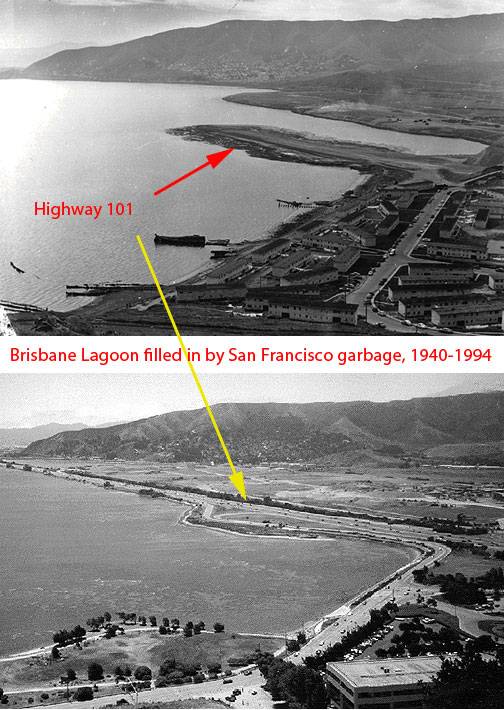

San Bruno Mountain in the foreground, looking north-northwest with the Golden Gate visible at the northern edge of San Francisco and Marin County across the water. Highway 101 runs across the lower right hand corner, enclosing the remains of Brisbane Lagoon to its left (west). Pacific Ocean in upper left corner.

Photo: San Bruno Mountain Watch

“Here lies one of the greatest assemblages of rare and endangered plants and animals in an area of such small size anywhere in the continental United States ... a natural area supporting close to twenty varieties of exceedingly uncommon organisms, all of which are in some danger of disappearing clean off the face of the earth.” —Mountain defenders David Schooley & Larry Orsak

San Bruno Mountain, early 2000s, from above.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

| Lying just south of San Francisco, San Bruno Mountain is a sanctuary of wilderness for rare and endangered species. The mountain has been the subject of years of litigation and lobbying, a contest between competing interests of development and wildlife protection. Despite making further development illegal in the 1970s, a legal loophole known as the Habitat Conservation Plan enabled developers to build on protected land if they submitted plans to replace lost habitat elsewhere or otherwise mitigate losses. While such plans have largely failed and generally worsened ecological conditions, San Bruno Mountain still remains home to a vibrant and unique biosphere and home to many endangered species. |

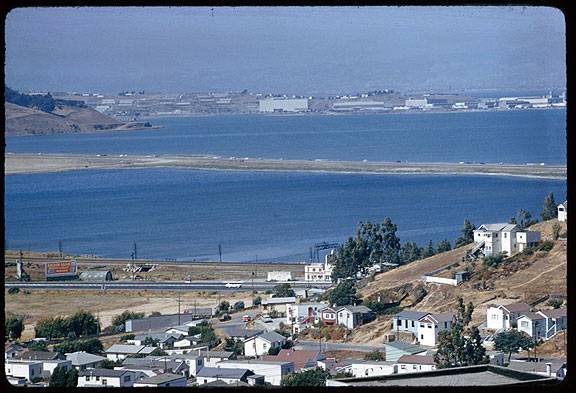

San Bruno Mountain is the last island of wildness at the southern edge of San Francisco and its peninsula. The first view of it is north on Highway 101 from the airport toward San Francisco. We see a very large, apparently barren hill, which is marked with the white letters on its low southern side “South San Francisco: The Industrial City.” As the freeway jogs east around it at Sierra Point, Candlestick Park appears to the northeast on the bay's shoreline. Beneath this point was once an Ohlone midden or shellmound, at the meeting place of mountain and bay. Other shellmounds still exist higher up on the mountain's southeastern flank. The mountain climbs up to our west, holding the town of Brisbane and the adjacent Crocker Industrial Park in its lap (known as Guadalupe Canyon).

To our left (west) as we drive north toward San Francisco is what's left of the Brisbane lagoon, where the bay once lapped against sandy cliffs. The area was San Francisco's garbage dump for 30 years, and is now home to six separate federally-designated Superfund toxic waste contamination sites. The road itself was built on a causeway made of landfill dumped during the 1930s, putting a barrier between most of the lagoon and the bay. Later the roadway provided a new eastern shoreline boundary as the lagoon was filled in with garbage and the dirt from the more southern of the two peaks near Candlestick Point.

San Bruno Mountain surrounded by cities and in this 1948 photo, farm fields to the west in Colma.

Photo: San Francisco Planning Commission archives

In 1884 Charles Crocker, one of the Big Four builders of the Central Pacific Railroad, acquired San Bruno Mountain. After his 1888 death and the distribution of his estate, the mountain passed to the Crocker Estate Company that later became the Crocker Land Company. They held the mountain continuously to the recent past. Ironically, it was the contamination caused by the stench blowing up from the garbage dump in Brisbane Lagoon that saved San Bruno Mountain's eastern flanks from massive development earlier in the 20th century. From 1965 to the present, several proposals for the development of San Bruno Mountain were made. The wildest was a proposal to remove approximately 200 million cubic yards from the ridge of the mountain and use it to fill the bay for the airport and a southern crossing bridge. This plan was the impetus for organized opposition, leading to the Committee to Save San Bruno Mountain and later San Bruno Mountain Watch.

In 1970 mountain real estate was transferred to Foremost-McKesson Inc., which in turn passed it along to Visitacion Associates, a consortium of Foremost-McKesson and Amfac, Inc. Visitacion Associates then co-owned 3600 acres of San Bruno Mountain with the Crocker Land Company. Visitacion Associates proposed a massive development in 1975, slated for 8,500 residential units and 2 million square feet of office and commercial space. Years of contentious litigation and lobbying ensued. In 1978 Crocker Land Company settled litigation with San Mateo County by donating 546 acres and selling the county 1100 acres of land along the main ridge, which later became San Bruno Mountain County Park. The state of California later bought and donated 256 more acres making the park 1,900 acres.

In the late 1970s the US Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Mission Blue Butterfly as an endangered species and that made any further development on San Bruno Mountain illegal, since what remained of it was habitat for the Mission Blue (and later the Elfin and Silverspot Butterflies, the SF garter snake). The development pressure led to a compromise and a new legal loophole in the Endangered Species Act (10A) called the Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP). This plan allowed developers to work with local activists and forge a compromise that allows development to proceed. Essentially the HCP allows a builder to develop land on endangered species habitat if they submit a plan to set aside other land for new habitat, or in other ways “mitigate” the losses to the species, supposedly leading to an improvement in the species' chances for survival.

The whole concept sits on shaky scientific grounds, since the science of ecology and species stability/evolution is seriously understudied. In the case of San Bruno Mountain, the plan to create new habitat for the Mission Blue, San Bruno Elfin and Callipe Silverspot butterflies has failed utterly. The invasive plant gorse is still there and actually the number of invasive exotic species has nearly doubled since the inception of the plan. “There are now more invasive plants occupying greater areas and displacing more native plants than at the HCP's inception,” said Ray Butler and Jake Sigg, officials of the California Native Plant Society writing in the Summer 1993 issue of Endangered Species. Two large areas of the mountain, Paradise Valley and the Northeast Ridge, have meanwhile been bulldozed and graded, only to lose funding and therefore HCP funds as well. In June 1994, they stand barren and dusty, denuded of their once rich life. Fortunately, more than 1,000 acres still teem with life in a dozen microclimates. Several dozen species of native plants, many threatened, persist along with endangered butterflies and snakes.

The former habitat for Mission Blue butterflies on the northeast ridge was bulldozed and filled with housing, seen here in 2020 from the east where Brisbane Lagoon once was.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Naturalist James Roof argues that San Bruno Mountain is the southern flank of the Franciscan region, a distinct bio-region, or eco-niche, among California's myriad possibilities. Fortunately, since he was an aspiring botanist as a young man wandering the hills south of Daly City and the west side of the San Francisco peninsula, he noted and gathered the native species and started Tilden Botanic Garden in the Berkeley hills. In the case of Leo Brewer's manzanita, Roof's garden became the its last refuge after a fire destroyed the remaining members of the species on San Bruno Mountain. It has since been re-introduced to its former home when the Botanic Garden arranged with the HCP manager to place eight plants back on the mountain.

Detailed history of San Bruno Mountain and the folks who have worked to save it (pdf)

One of the great ironies of local ecological history is that it is probably the garbage smells blowing onto San Bruno Mountain from San Francisco's garbage being dumped into Brisbane Lagoon (seen here in 1940 and 1994 from Bayview Hill) that kept it from being thoroughly developed at an earlier time in history.

1940 photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA; 1994 photo: David Green

July 20, 1957: Highway 101 causeway with Brisbane Lagoon in foreground. Note Bayview Hill with no Candlestick landfill or stadium, nor does Candlestick Point State Recreation Area exist yet.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P09410)

In this 1948 aerial photo, the northeast ridge of San Bruno Mountain is still unscathed by the Guadalupe Canyon Parkway, or any of the housing projects that were built at the end of the 20th century.

Photo: San Francisco Planning Commission archives

At about 3 a.m. on June 11, 1916, three electrical towers were dynamited on San Bruno Mountain about ten miles south of SF. The towers, owned by Sierra Light and Power Co., supplied United Railroads' electrical power. The damage was slight. Someone had thoughtfully arranged for alternate power and streetcar service was not interrupted. Word was circulated that Tom Mooney was responsible for the bombing...

San Bruno Mountain from north to south, 2015.

Photo: Adriana Camarena