Mission High School’s Innovative Anti-Racist Teaching

Historical Essay

By Kristina Rizga

The June 3, 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstration after the George Floyd police murder in Minnesota began in front of Mission High School on 18th Street.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

When [Eric] Guthertz was hired as an English teacher by Mission High in 200l, the school had been coming to terms with the disappointing outcomes of a radical "reconstitution" plan implemented in 1996-1997, calling for tougher accountability: the district removed the principal and fired all teachers, as a solution to low standardized test scores. The plan didn't work. By the time the new principal Kevin Truitt came on board in 2001, the school had the lowest test scores and attendance rates among all city high schools, suspensions were up and more teachers were leaving Mission than any other school in the district. With Truitt on board, the school was looking for alternative ways to address its low performance and persistent achievement gaps in grades, attendance, and graduation rates. Like most schools across the country, despite endless new state and district initiatives, "more rigorous" curriculum, and "tougher" accountability measures, the dial wasn't moving.

The cash-strapped California school had also just received some money from the Gates Foundation and the district, a grant designed to fund the creation of smaller high schools and implement school improvement recommendations based primarily on the research of Linda Darling Hammond, professor of education at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. Darling-Hammond is a highly respected researcher among teachers, and the school was enthusiastic about implementing her suggestions. One of her recommendations included increasing paid time for teachers to plan lessons together and discuss outcomes to see if their methods worked. Because Guthertz had experience planning lessons collectively and sharing student work from his job in East Los Angeles, Principal Truitt asked him and eight other teachers to lead this new experiment at Mission.

"Back then, there were only a few groups of teachers who met informally to plan lessons together, but for the most part teachers worked in isolation," Guthertz recalls. "There were some people who said they didn't want to collaborate and very few teachers were willing to share student work with each other." Guthertz and his teacher-leader allies started working to spread new norms throughout the school: encouraging teachers to discuss their students collectively, share best practices, and plan lessons cooperatively. When it came to looking at student work together, there was more resistance, but Guthertz took the initiative and started meeting with two colleagues in the English department to grade and discuss student writing together.

Around this time, in 2002, the school administration worked on implementing another teaching approach, which Darling-Hammond calls "Multicultural and Anti-racist Teaching." This research-based pedagogical approach argues that many students of color have negative experiences in schools—and society—that undermine their own conception of their ability to succeed academically: Darling-Hammond; like other education researchers such as Lisa Delpit and Claude Steele, argues that schools need to be set up as intentional communities to combat these "stereotype threats." This research demonstrates that integrated classes, personalized teaching that engages student intellect, culturally relevant curriculum, and a school culture that doesn't force students to reject their home cultures have shown increases in achievement. (Linda Darling-Hammond, Redesigning Schools: What Matters and What Works, Stanford, CA: School Redesign Network at Stanford University, 2002, 33)

To implement these changes, the schoo1 initially followed a more typical, top-down strategy of reform: the state sent in a consultant to implement changes. "It was an outsider, who came in and talked about the civil rights movement and did touchy feely group discussions," Guthertz recalls. "Someone else came in and for one day taught behavior management strategies that focused on controlling and penalizing students versus making changes in teaching practices that would engage and support them. That blew up at the school. The administration got rid of that program.” The issues that come with this kind of approach to school reform—"do what the district, state, or consultants say"—have been a recurring theme in the long careers of Guthertz, Roth, and McKamey. "It comes off as an attempt to hijack the effort by the teachers to think about education," McKamey comments. "It's the deepest disrespect. The teacher has been teaching for ten years and someone is going to come in and say, 'I'm going to show you something.' Most of these people have never taught in the classroom."

In 2005 Principal Truitt called together a small group of teachers, including McKamey (who had joined Mission High a year earlier as an English teacher) and Guthertz (Roth wasn't working at Mission High yet), and asked them to come up with their own solutions for incorporating "anti-racist teaching" and reducing racial gaps at the school. "We started very slowly, getting to know each other,” Guthertz says. "What would a school focused on equity look like? We talked about curriculum, pedagogy, and affect: what you teach, how you teach, and your relationship with the students." Because African American students had the highest dropout rates and received the largest proportion of Fs and Ds at the school, administrators and teachers at Mission High agreed to focus on this subgroup first, extending their work to Latino students the following year.

McKamey insisted on starting out by making a video of interviews with African American students describing their experiences at Mission. “What interests and inspires teachers? Students," McKamey says, explaining why she wanted to start with the voices of students. "The following year, we did a panel with Latino students with the same intent.” McKamey insisted that teachers interview students who were "in the middle": succeeding in some classes and struggling in others. Educators have a tendency to focus on the most underachieving African American students, McKamey says. This typically shifts the conversation to the personal challenges students bring to school, rather than forcing teachers to notice and discuss strategies that work.

As African American students discussed the kind of classrooms that helped them succeed and motivated them to come to school (teachers' names were not used), similar themes and patterns emerged. Students said they learned best when teachers broke down the content and skills for them, saw and heard them as individuals, understood the particular strengths of their students, paid attention to their goals, and gave them specific tools to achieve their ambitions. Students also noted what didn't work: teachers who seemed rigid or downright mean. They talked about teachers who noticed what they weren't doing right—coming to class late, not turning in an assignment—rather than everything they were doing correctly: coming to class despite challenges at home, working hard in the classroom, participating in discussions. The students also talked about getting bad grades but not fully understanding why.

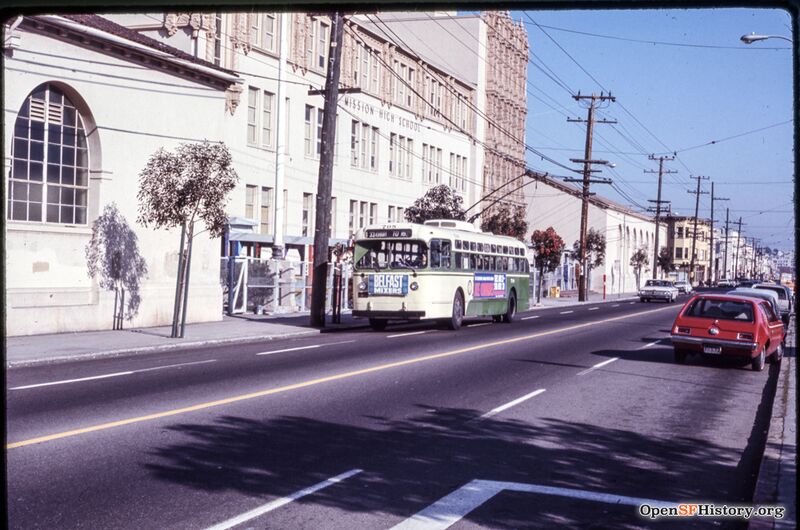

Mission High from Church and 18th, 1972.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp25.2504

“At the center of what the students said was that how the teachers saw them elicited a feeling," McKamey recalls of those interviews. "They said they could tell how the teacher felt about them by the way the teacher looked at them or talked to them. So, they read the teacher's response to their work, behavior, and oral contributions in class as a response to them as human beings. Why did one teacher understand what they were trying to accomplish with their writing and another think it was just a paper of problems to solve? Why did one teacher praise a student's comments in class, even if they were spoken out of turn, while another did not even bother to acknowledge that a student had spoken? The sense the students made of all this was that some teachers wanted to work with them and others just didn't. This played out in terms of a student's uneven performance; for teachers who cared and supported them, no matter how inexpertly, they gave great effort, often exceeding their own expectations. For the others, those teachers that did not express care, they languished."

McKamey and her colleagues then made another video in which they interviewed Mission High staff about teachers who had made a difference in their lives. “Our work was always about trying to touch that place of joy and meaningfulness, help teachers reconnect with what we are doing, what we are about, in the middle of all the sweat and hard work and frustrations,” she says.

The teachers played the videos at a school-wide faculty meeting that was followed by a discussion. The videos were well received. Shortly afterward a committee of about fifteen teacher-leaders and several administrators started to meet to investigate specific areas of concern and design solutions. "We were always looking at and trying to understand different kinds of data, including anecdotal,” McKamey tells me. "Then we would settle on something we needed to concentrate on each year.” They voted to call the working group the Anti-racist Teaching Committee. "Some people were upset about the name, but we talked about it openly," Guthertz says. "The idea behind it is to signal explicitly the idea that if you don't keep the conversation about racial achievement gaps at the forefront, institutionally and systemically—like how you structure your Advanced Placement and honors classes or how you engage or scaffold students individually—the structures can fall back to the status quo again really quick."

The following year Guthertz decided to accept the job of assistant principal. He felt he would have more impact implementing systemic changes across the school, including the expansion of teacher-driven professional development. McKamey was given the position of instructional reform facilitator. The committee now started looking systemically at the achievement gaps in grades of African American and Latino students, attendance, referrals, and graduation rates. History teacher Amadis Velez became the go-to person to translate raw data into accessible charts and graphs for other teachers. The committee leaders were constantly walking through classrooms and talking with other teachers and students to gather more qualitative data.

In 2008 Principal Truitt took a leadership position in the district, and Guthertz took the job of principal. The next three years were a time of visible improvements in a broad range of qualitative and quantitative measures. Suspensions and dropouts went down. Attendance and college acceptances went up. The achievement gap in grades went down. When Guthertz and l met for the first time in his office in 2010, he was quick to point out that although the media often credit him with all of the improvements, these changes were a result of the foundation that Principal Truitt laid with the teachers and the work of current administrative leaders and teacher-leaders like Roth and McKamey. Journalists, and studies also often connect shifts in yearly test scores to one-dimensional, recent changes, he says, while overlooking years of work and multiple, overlapping initiatives that improve teaching. Americans love "big changes" in one year, but school reform is incremental, slow, and messy, and the results often don't show up for five years or more, he notes.

In his role as principal Guthertz always seeks to promote the kind of work that helped him grow as a teacher by building an open and trusting environment in which teachers are empowered to investigate issues and design their own solutions. School reform has to originate from the base of your school, Guthertz and Roth argue. It has to come from and be owned by staff. It can't be parachuted in from the district or state. Guthertz is disheartened by the national conversation that focuses most of its energy and dollars on a "deficit-based" model of sorting and tracking teachers just like we do with students. Instead of asking, "How can we measure and fire 'bad teachers' faster?" Mission High chooses to focus on how to help teachers become better. Most of our country's 3 million teachers are dedicated professionals and need sustained opportunities to improve, Guthertz says. The go-to approach to building a better teacher—occasional common planning of lessons and using test scores and sporadic observations to evaluate educators—doesn't help teachers improve their practice in meaningful and systematic ways. Teachers need daily opportunities to plan lessons together, analyze student outcomes, and receive thoughtful, one-on-one coaching.

Student engagement is not possible without teacher engagement, McKamey says. When teachers are treated with respect as professionals, they are intrinsically motivated and engaged in their job. Teachers can't teach for twenty-five years and stay engaged in their work if they are not constantly challenging themselves and given a voice in their growth process.

As a part of the alternative, teacher-led school reform strategy at Mission, Guthertz empowers the two co-chairs of each department to come up with their own ideas on how to improve the quality of student work and instruction in their departments. One year, for example, the social sciences department prioritized concentrating on teaching analysis and then detecting, grading, and commenting on those outcomes in student writing. The same year, the members of the math department focused on planning lessons together, thinking about sequencing different concepts that are aligned to state standards, and calibrating their grading rubrics.

One of the strengths of the teacher-driven community strategy is that it doesn't follow a top-down, rigid model, Guthertz tells me. It shifts and evolves organically, from the inside out, depending on the needs that teachers detect in the data. Meanwhile, the Anti-racist Teaching Committee, led by McKamey, is making sure that the racial disparities in achievement are not moved to the back burner, as often happens when teachers dive into the complexities of building new structures and making changes in their classrooms.

Mission High School, 1935.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp14.10407

Guthertz says that today, almost all teachers participate in collaborative curriculum planning and meet to discuss support for students they share. Most are open to observation, coaching, and observing others. There are daily conversations throughout the school about data, and staff members are constantly tinkering with existing programs in an effort to make them more effective, as the student body and school dynamics change. After years of building trust, many teachers analyze student work together now, although this process still lacks systemic consistency and could be more productive, Guthertz admits.

Most of this teacher-driven work of improving learning for all students wasn't in place when Guthertz first started working at Mission. He believes it has become more embedded throughout every part of the school as a result of the teachers' leadership. But that doesn't mean there aren't challenges, he says. College enrollment among Latino students has gone down slightly. The numbers of African American and Latino students in AP math and science classes don't fully mirror the larger student body of the school. The passing rates for African American and Latino students on the California High School Exit Exam went down in 2013 and 2014. The work continues.

Teachers have varying opinions about the reasons for the achievement gaps at Mission High and how Principal Guthertz is leading the school to make changes. Even though his evaluations by teachers are among the best in the district, as in every organization, opinions differ. Some teachers say that he pushes for radical changes too often. Although the majority of teachers are comfortable with his changes, a few have become vocal opponents. Some have told me that they want to see Guthertz more in the classrooms, pushing improvements in the quality of teaching. But there is clear agreement among most teachers that Mission High is a good place to work because Guthertz is one of those rare principals who deeply respects teachers and is supportive of their craft.

"The devotion level among teachers has gone up in the past ten years," science teacher Rebecca Fulop, who has worked at Mission High for a decade, tells me. "No one here does 7:45 to 3:10 and then calls it quits. That by itself doesn't necessarily make teachers effective, but the dedication here is extraordinarily high. The joyfulness of learning has increased. Most kids want to come to school. Respect of students toward teachers and students toward other students has increased."

"I love working at Mission," security guard Iz Fructuoso, who has worked at the school for eight years, tells me: "We have a real community here." As someone who has worked in inner-city schools for twenty-two years, Fructuoso says that one of the most important things for a healthy school climate is stability. She says that when she worked at the Luther Burbank Middle School with Roth and McKamey before it closed in 2006, it felt like the school had a new principal every year. "A new man would come in and change all of the rules around, again," she recalls. "This makes kids feel like adults are not in charge. Students need consistency and clear structures."

Guthertz knows that some teachers are critical of his decisions. He admits that the more democratic, "shared leadership" that he fought for as a teacher in Los Angeles in 1989 is not an easy process. "Our teachers have a voice in the budget, a voice in the class offerings, a voice in the master schedule, a voice in discipline policies, curriculum, pedagogical approaches. Yet teachers still sometimes say in surveys that they don't feel like they are being heard. We may have a shared vision, but two priorities could be at odds sometimes. So, sometimes I have to make decisions and get used to not being popular. It's not my strength. I don't like being mean. I prefer being kind, but confrontation is critical sometimes."

Mission High at dusk, 2022.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Excerpted with permission from Mission High: One School, How Experts Tried to Fail It, and the Students and Teachers Who Made It Triumph, Bold Type Books: 2015