Mayor James Phelan

Historical Essay

by Robert Cherny

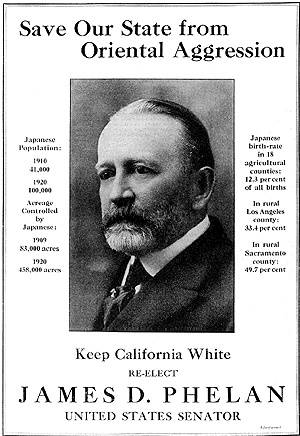

James Phelan unsuccessfully ran for U.S. Senate in 1920. His campaign slogan in the in the 1920 Senatorial Election was "Keep California White."

Image: Bancroft Library

James Duval Phelan, January 4, 1897 -- January 8, 1902

Born in San Francisco in 1861, he grew up Catholic, studied at St. Ignatius College (now the University of San Francisco), and traveled extensively in Europe as a child and young man. His Irish-born father left him a fortune, but Phelan took little interest in what he once called "the sordid messes of business and trade." He saw himself instead as a political leader and patron of the arts. Aloof, cultured, and aristocratic, he served as mayor from 1897 to 1901, as one of California's United States senators from 1915 to 1921, and as the leader of the state's Democratic party from the late 1890s through the 1920s.

Phelan's vision derived in significant part from his readings in the classics and his travels abroad. Paris, Rome, and Athens, especially, figured prominently in his speeches—he loved to make speeches—by which he defined much of his vision. His vision was a complex one, including the built environment, city government, and social patterns.

James Phelan in the 1890s, before he became Mayor.

Photo: Bancroft Library

Perhaps the best known aspect of Phelan's vision of the city was his commitment to beautification. He stands among the leading proponents of the City Beautiful, that turn-of-the-century movement committed to making cities more attractive places to live. Inspired by the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, the City Beautiful movement emphasized classical, monumental architecture and a harmonious, symmetrical relationship among buildings. Phelan adorned the city by contributing for decorative fountains, monuments, and statues, and by encouraging others to do the same. He never tired of promoting a plan to extend the Golden Gate Park Panhandle to the intersection of Van Ness and Market streets. But, for Phelan, such individual efforts needed an overall design to be most effective. Toward that end, he took the lead in securing the famous Burnham Plan of 1905.

While James Phelan bears major responsibility for bringing Burnham to San Francisco, his own vision of the city was more complex than the Burnham Plan. As president or director of several banking and insurance companies and owner of extensive city real estate, he was well aware of the economic life of the city. He shared the vision of San Francisco as economic capital of a Pacific empire and once called San Francisco "the handmaid of commerce between the western shores of the United States and the lands facing the great Pacific ... the capital of an empire."

But Phelan saw the city as much more than an economic marketplace. Phelan believed that the city could only be great if, like Paris under Haussman, it used its wealth to "develop the fine and useful arts and sciences to an unparalleled degree." To Phelan, greatness also required that a city be "clean . . . and healthful; [and] that its children be properly instructed."

Phelan's vision of the city gave close attention to what today would be called the infrastructure. As mayor, he promoted bond issues for a new sewer system, city hospital, parks, and schools. The people, he thought, deserved efficient and effective public utilities—water, gas, electricity, and transportation—and, reflecting the emergence of municipal progressivism, he advocated government operation of essential utilities. He felt that the nineteenth-century pattern of granting franchises to private corporations to provide public utility services created an inevitable conflict between the corporations' need to make a profit and the public's need to receive necessities efficiently and at the lowest cost; efforts to regulate a monopoly, he warned, only led the monopoly to corrupt the political process. The late nineteenth century and early twentieth century had presented repeated examples of the corruption of city politics by utility corporations anxious to secure or protect their franchises; in one of Phelan's earliest speeches, in 1889, he drew attention to the dangers of monopolistic utility companies. For Phelan, the answer was obvious: the city should own all these utilities, thereby—he thought—reducing costs and eliminating corruption. Toward the end of his career, in 1922, he proclaimed that "I am now, and always have been, in favor of the public ownership of such utilities."

As a result in major part of his efforts Article XII of the new city charter that took effect in 1901 pledged that "It is hereby declared to be the purpose and intention of the people of the City and county that its Public utilities shall he gradually and ultimately owned by the City and County. Throughout his career, Phelan worked to realize the intent of Article XII, both as public official and private citizen. In July 1901, as a private citizen, he applied for the right to use the Hetch Hetchy Valley as a reservoir to prevent it from falling into the hands of speculators, transferred his claim to the city in February 1903, and played an important role in bringing the Hetch Hetch Project to reality. He continually advocated that the city should directly sell San Francisco citizens not only water (by buying out the privately owned water company) but also electrical power (by buying out the holdings of PG&E within the city). Similarly, Phelan in 1906, as a private citizen, incorporated the Municipal Street Railways of San Francisco to acquire existing streetcar franchises when they became available and later to transfer them to the City.

Phelan's vision of the city, it must be noted, contained clearly elitist elements. Pericles's beautification of Athens -- one of the models for his own vision—had been intended, Phelan claimed, to "render the citizens cheerful, content, yielding, self-sacrificing, capable of enthusiasm." Along with proponents of the City Beautiful, Phelan may have seen the monumental architecture of the movement as a means of refining public taste, prompting civic pride, and promoting respect for the state, especially among recent immigrants and among the working class. Daniel Burnham's justification for formal and symmetrical tree-planting reveals such a concern: "this amounts to a lesson of order and system, and its influence on the masses cannot be overestimated." In seeking election, Phelan solicited the votes of workers, but in choosing a Committee of 100 to make charter revision recommendations, Phelan appointed only four working-class representatives. The charter reforms he supported included strengthening the mayoral powers and instituting at-large elections of supervisors, which potentially reduced working-class representation. During the years from 1902 to 1911, he consistently opposed the Union Labor Party, which drew its electoral strength from workers. In all, Phelan's record suggests that he saw the political role of the working class as limited largely to electing men such as himself to govern.

Phelan's vision of a clean, beautiful, efficient city was also a city for whites only. He considered people of color as incapable of being assimilated, culturally or physically, and therefore saw them as a threat to the cultural values he sought to promote through beautification and his patronage of the arts. He vehemently opposed immigration from Asia, and favored the segregation and disenfranchisement of peoples of color already here. He cut his political eyeteeth on anti-Chinese rhetoric's and, in 1912, wrote that "This is a whiteman's country ... We cannot make a homogeneous population out of people who do not blend with the Caucasian race." While he declared on the floor of the U.S. Senate that African Americans were "a non-assimilable body, a foreign substance," his major antagonism was reserved for immigrants from Japan, who, he argued, "will destroy American civilization as surely as Europe exterminated the American Indian." His campaign slogan in the in the 1920 Senatorial Election was "Keep California White."

Phelan's vision of the city was complex. Phelan accepted the notion of San Francisco as seat of an economic empire, but added other elements to his vision: promotion of culture and learning, a monumental approach to civic beautification, efficiently-run and municipally owned public utilities,and a racially homogeneous society. Phelan borrowed elements in his vision from others and presented a vision that was widely shared. Significant elements in it became public policy—most notably, city ownership of its water and street transportation systems and the adoption of a few elements of the Burnham Plan, such as the civic center. In the end, however, the city failed to use the Burnham Plan as a comprehensive blueprint for a "San Francisco Beautiful," even when the 1906 earthquake provided a unique opportunity to do so; hopes for municipal ownership of gas and electrical systems failed against the political prowess of PG&E; and Asian exclusion and segregation ultimately gave way to more tolerant policies and practices.

—Robert Cherny, excerpted from "CITY COMMERCIAL, CITY BEAUTIFUL, CITY PRACTICAL: The San Francisco Visions Of William C. Ralston, James D. Phelan, And Michael M. O'Shaughnessy," originally published in California History magazine, Fall 1994