MCO and Latino Community Formation

Historical Essay

Listen to an excerpt from "All Those Who Care About the Mission, Stand Up With Me!" by Tomas Sandoval (read by Adriana Camarena):

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/13TenYearsMissionCoalitionOrganization" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

by mp3.

![]()

Previous stop: Flowering communalism

Next Stop #14: Women's self-health

Beginning in 1967, the largely working-class, heavily immigrant, and decidedly multiracial neighborhood of the Mission District underwent a profound transformation. Incited by the specter of urban redevelopment, and set against the backdrop of local movements for racial justice, this multigenerational population of both the politically-active and previously uninvolved came together under the common cause of community as embodied in the MCO. Called the “largest urban popular mobilization in San Francisco’s recent history,” they united for jobs, housing, education reform, and the power to implement their collective vision.(2) In the process, they asserted a powerful sense of cultural citizenship, “of claiming what is their own, of defending it, and of drawing sustenance and strength from that defense.”(3) By 1973, when the formal organization declined, the Mission remained a far more cohesive community than it was before, reshaping their sense of collective identity in fundamental ways.

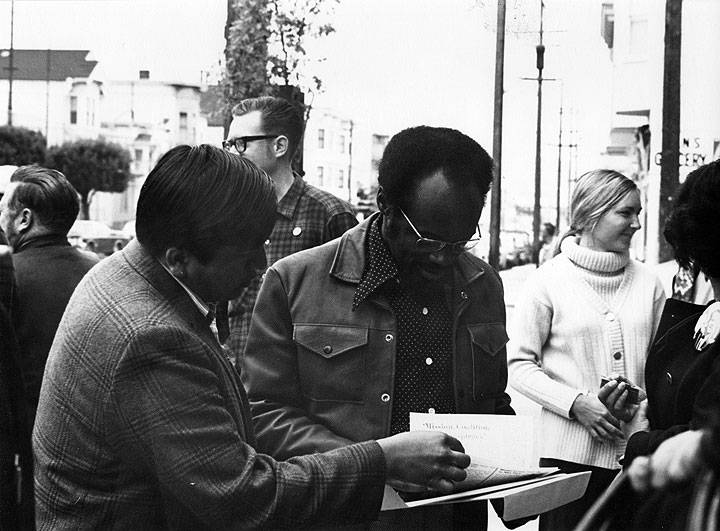

MCO Housing Chair Flor de Maria Crane speaks with Supervisor Terry Francois and Assemblyman Willie L. Brown, Jr. (at right) during press conference, c. 1971.

Photo: Spence Limbocker, courtesy El Tecolote archives

Designed as a grassroots, multi-issue coalition composed of scores of local organizations, the MCO actively involved 12,000 residents who sought democratic control over their neighborhood on behalf of the more than 70,000 people who lived there. At its height, the MCO became an institutional force, both the recognized voice of the district in political circles and the local group controlling funds from the Model Cities Program—a 1966 community development effort by the federal government mandating citizen participation. Through an assortment of programs and campaigns, they made lasting and meaningful changes to the infrastructure of everyday life for both contemporary and succeeding generations of local residents. The legacy of the MCO—balanced on a multiracial and working-class population successfully claiming rights and ownership over their neighborhood—extends beyond the programmatic. In the ways it envisioned its collective effort, and integrated and deployed the racial/ethnic diversity of the Mission, the MCO nurtured a collective community identity within the population largely of Latin American descent. As a result, they recreated the historic community identity of the Mission District, substantively rooting a hybrid and shifting form of class-based latinidad in the neighborhood, an identity which continues to shape its present in myriad ways.

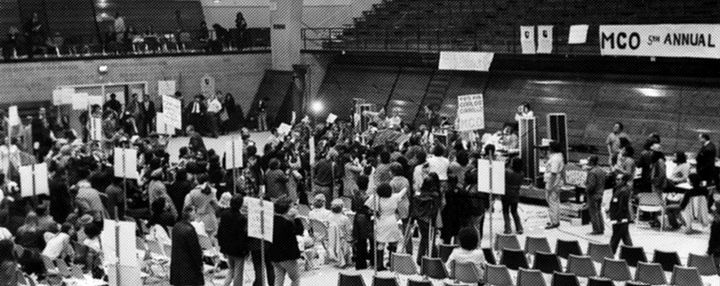

MCO's 5th annual convention, 1972, at USF.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

“We are mainly a Latin American community which is proud of its heritage,” proclaimed Ben Martinez at the second annual convention of the Mission Coalition Organization (MCO). Standing before more than 800 community leaders—collectively representing 81 local civil rights, labor, church, and community organizations—Martinez publicly recognized the new dominant racial/ethnic group in the Mission as the foundation of coalition-building. “But this is also a mixed community,” he continued, “and I know that the Samoan, the Black, the Italian, the Irish, the Filipino, the American Indian, the Anglo, and every other group in this community is proud of its heritage.” Speaking as president of the MCO in October 1969, Martinez had already overseen a growth in membership, programs, and public reputation for the fledgling organization. Now, hoping for more success, he addressed a looming limitation to the collective and grassroots effort of this poor, diverse neighborhood. “It is in our interest to recognize the identity each of us has, and then to go from that point to developing a working program that will meet all of our interests.”(1)

In the spring of 1966, the cause of urban renewal served as the catalyst for this transformation. On the surface, the Mission seemed an ideal candidate for renewal, or publicly-funded development to cure urban blight. By mid-decade, however, the promise of federal dollars for local redevelopment created a backlash within poor and working-class communities in the City. An urban renewal project in the Western Addition, rather than improving life for the primarily Black, working-class residents, resulted in massive dislocation, leaving the area’s core surrounded with vacant lots, public housing units, and a growing crime rate. Widely studied as an example of failed urban planning, and popularly understood as urban removal, by the 1960s the bureaucratic buzzwords of “urban redevelopment” incited fear among the City’s communities of color. Not surprisingly, when rumors of a proposed study by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA) circulated through the Mission, constituencies as seemingly disparate as landlord and tenant found a common ground of opposition.

In 1966 the SFRA secured funds for a study of the “Mission Street Corridor,” the core of the district where BART construction would be located. Almost immediately, local property and business groups organized their opposition. Led by realtor Mary Hall and self-described “right-wing populist” Jack Bartalini, the conservative group included longtime homeowners’ associations like the Potrero Hill Boosters, East Mission Improvement Association, and Noe Valley Improvement Club, in addition to local merchants. Each feared the proposed clearance of deteriorating properties and the forced relocation of businesses, labeling the downtown-led redevelopment “creeping socialism.”(4)

Bartalini and Hall spoke for constituencies with political clout but a diminishing presence in the Mission. These mostly White, propertied residents with long roots in the district had been joined in the previous decade by a multiracial mix of migrants, most with roots in Latin America. Local officials and the press noticed the growth of the Spanish-speaking population at roughly the same time as the growing exodus of White ethnics and declining conditions in the Mission, leading some to suggest the two were connected. One local resident expressed the views of many when he described the Mission as “running down something awful. Twenty years ago, my wife and I used to stroll around the block after supper, but the streets aren’t safe at night anymore.” To others, the newcomers represented the future potential of the neighborhood, informing formal efforts to assure “they’ll want to stay.”(5) Indeed, in the eyes of many informal leaders of the neighborhood, the multiracial population embodied the strength that had always marked the Mission’s past. As one local priest put it, “whether they were Spanish-speaking, English-speaking, or they came from Nicaragua or Guatemala—whatever part of the world—they were neighbors.”(6)

Though few noticed, the “new” Mission had already begun addressing the issues of working-class renters in a neighborhood in structural decline. These Latin American organizational efforts also helped constitute the collective voice of the new majority in the struggle against redevelopment. For their constituencies, the prospect of urban renewal was mixed—it meant the possibility of new jobs in both construction and subsequent business and commercial development, but at a potentially fatal cost. Even the SFRA estimated the “improvement activities” would result in the displacement of “1,900 families and 1,300 single individuals.”(7) When coupled with the known outcome of earlier development plans, leaders of Latin American descent knew that any future their constituencies had in the City depended on their ability to organize an effective opposition. Just such a coalition began to emerge when organizations—all in some way committed to empowerment of the Latin American community—began to craft a unified voice for the Spanish-speaking.

The Latino wing of the opposition included groups like the local chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), a statewide, grassroots Mexican-American group with a presence in the City since the 1950s. One of their local leaders, Herman Gallegos, was perhaps the most respected Latino voice in the City at the time. While still a part of the CSO, Gallegos helped establish OBECA/Arriba Juntos, a pro-integration effort “to prepare Hispano Americans to enter the job market.” Based out of Catholic Charities, the group’s other leader—Leandro Soto—had begun helping Latinos connect their needs to federal efforts as part of the War on Poverty. Their interests were further served by groups like: the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA) and the League of Latin American Citizens (LULAC), both decidedly political organizations; the Catholic Council for the Spanish Speaking, an institutional effort holding some influence in this decidedly Catholic town; and the Mexican American Unity Council, Puerto Rican Club of San Francisco, and others dedicated to cultural, educational, and civic endeavors. As established and respected organizations, each added credibility to the anti-redevelopment movement, as did leaders like Gallegos, perhaps the informal representative for the Spanish-speaking in local politics.

Other groups also lent support, further suggesting the depth of local opposition. Local labor—who theoretically had much to gain from redevelopment—added another base of anti-redevelopment support. The Mission’s most prominent union was the Building and Construction Workers Union, Local 261; their support came most visibly via Abel Gonzalez, head of the union caucus Centro Social Obrero. Focusing on service issues for the Spanish-speaking population in the union, the Obreros had made a name for themselves through their popular English-language classes and citizenship programs. The Catholic Church remained a force in both neighborhood and citywide politics. Many of the City’s priests, committed to a philosophy of social change, viewed support for the poor as synonymous to their religious ideal of service. Protestant churches, overcome by a progressive mission mentality, were already involved in local race politics, seeking to improve the material conditions of life in the City’s ghettos and barrios. Reverend William R. Grace, director of the Department of Urban Work in the Presbyterian Church, sought social change by implementing the grassroots model for change designed by Saul Alinsky. Grace’s assistant, Reverend David Knotts, already worked as a minister in the Mission.

Serving as a counterbalance to the conservative alliance represented by Bartalini and Hall, the Mission’s radical Left—consistently dedicated to fighting for the rights of the local poor—added another oppositional voice to the diverse mix. Skeptical of government-sponsored community development and proponents of mobilizing communities for their own control, the Progressive Labor (PL) Party worked to create a meaningful movement for change among the district’s poor. Led by John Ross, and finding organizational and representational focus in the Mission Tenants’ Union (MTU), their neighborhood influence flowered as they became widely-known as a credible voice for the rights of poor renters. As evidence of their success, despite their espoused dedication to a Marxist ideal, even politically-moderate church leaders sent their parishioners to the MTU when experiencing problems with their landlords.

Individually, each organization represented a slice of the Mission District. Joined together under the threat of redevelopment, they left few recognizable constituencies unrepresented. This unlikely merging of the neighborhood’s political and demographic diversity began in earnest when Bartalini called Ross. Revs. Grace and Knotts also saw the issue as a potential catalyst for a broad-based community movement. These varied efforts culminated in 1966 with the creation of the Mission Council on Redevelopment (MCOR). Though Bartalini and Hall demanded MCOR stand unequivocally opposed to the SFRA plans, the organizational base was more interested in creating an authentic representational body whose voice City Hall could not ignore. Only in that way could residents control their neighborhood’s future. To preserve that possibility, they did not oppose urban renewal, but instead sought the power of the veto over its local manifestation. Recognizing that goal could only be met if they legitimately represented their neighborhood, MCOR recruited the Catholic network, the Obreros, block clubs and tenants’ associations, Protestant churches, and various Latino organizations.

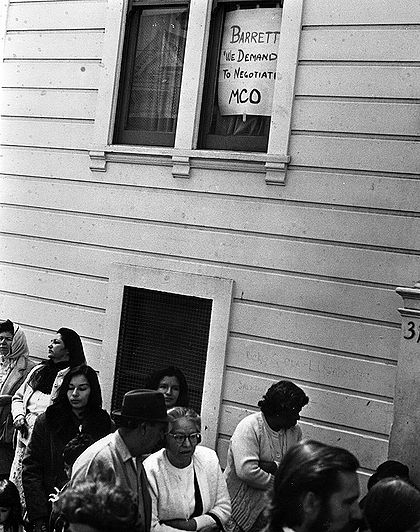

MCO picketers outside of Mission District building, 1970

Photo: El Tecolote archives

MCOR represented the authentic diversity of the Mission, inclusive of poor and middle class, propertied and renter, Catholic and Protestant, and the multiracial population who called it home. The Mission Renewal Commission—comprised of large, local merchants—represented the lone, local voice supporting urban renewal. Consistently asking, “Where am I in this picture?” as plans progressed, MCOR demanded everyday people be considered as redevelopment came before the Mission and, later, the Board of Supervisors. Though the homeowners left MCOR in opposition to their willingness to negotiate, and the Obreros and other labor groups provided only minimal support, MCOR emerged successful in the early winter. When Mayor Shelley could not accede to an MCOR veto, the group sought to scuttle any redevelopment efforts. In December 1966, faced with the overwhelming opposition of most of the community, the Board of Supervisors squashed renewal.(8)

Once they won the Board’s vote, MCOR—organized as a single-issue coalition—ceased activity in early 1967. The Mission, however, still confronted the fundamental issues inciting the city’s redevelopment crusade. In one square mile tract, representing the heart of the district, more than 2,000 units out of 15,000 were classified as deteriorating. Two hundred and sixty-two homes were listed as dilapidated. Local groups estimated that by the mid-1960s only 20% of the residents owned their own home. Additionally, residents confronted an inadequate education system, a lack of jobs and job training, and no effective political voice. Local grassroots organizers, in particular those focused on Latinos, sought to sustain the level of activism beyond MCOR. Single-issue and diffuse campaigns garnered some attention and success, notably revealing an emerging, new leadership. A young Latina named Elba Tuttle rose up in the Mission Area Community Action Board (MACABI). Martinez achieved prominence within the OBECA group. Reflective of the growth of Latino labor, Gonzalez and the Obreros helped secure the electoral victory of Mayor Joseph Alioto. As the War on Poverty began to provide funds for varied community efforts, community members also nurtured their political and organizational development. The lack of a cohesive effort, however, as well as growing conflicts over federal funds, revealed the deep fissures which remained due to the divisions of race, nationality, and generations. Mission activists were learning that “overcoming poverty is not simply a matter of political will; it is and has become even more one of political structure.”(9)

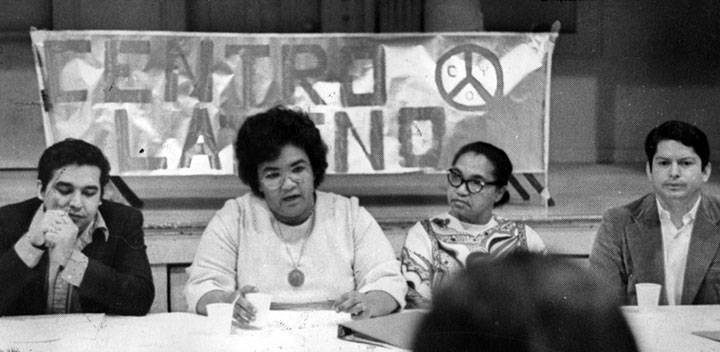

Manuel Larez, Elba Tuttle, and two others, c. 1971.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

The potential for structure seen in MCOR’s organizing strategies presented itself again in February 1968 at the Spanish-Speaking Issues Conference sponsored by MACABI. Mayor Alioto, speaking before the group, suggested he would seek Model Cities funds if a “broad-based group representative of the Mission” so desired.(10) The Model Cities Program—part of the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966—provided funds for community improvements ranging from structural development to issues like housing, education, employment, and health. Realizing the potential for a more sustained grassroots coalition, Rev. Knotts, Tuttle, Martinez, and others took the lead. By June 1968, a coalition of about 25 groups formed, calling themselves Temporary Mission Coalition Organization (TMCO)

Several key principles guided the MCO. First, it strove to be a multi-issue organization. Another was the principle of democracy, suggested by several structural elements such as a steering committee, which met weekly; a monthly council meeting; and an annual convention of member organizations. They remained dedicated to nonviolence, hoping to utilize the full tactical range of the Civil Rights Movement. Finally, they believed they could only succeed if they were representative. The commitment to a broad-based movement meant any and all identifiable constituencies in the Mission must be allowed to join. That meant making room for organizations with varied membership bases, as well as clear constituencies without active organizational outlets. They needed to represent the diversity of the Mission, a neighborhood composed of Central Americans (Nicaraguans and Salvadorans being the largest two groups, followed by ethnic Mexicans), Puerto Ricans, and South Americans, as well as Irish, Italian, German, Russian, Filipino, Native American/Indian, Samoan, and African-American constituencies. Organizers began their work of mobilizing support for the MCO’s inaugural convention, carefully strategizing to unify a cosmopolitan neighborhood.

As the first mass meeting of the MCO, the convention would foster their democratic ideal by providing for the selection of officials, committees, and bylaws. But it could only work if a representative group showed up. As the organizing group’s leader, Martinez sought to harness the support of labor, who had only been lukewarm participants in MCOR. Exploiting his close ties to Gonzalez, he recruited the Obreros, and Local 261 also provided financial support. Tuttle and John McReynolds focused on organizing the grassroots constituencies for the convention. Mike Miller—with connections to Saul Alinsky and experience in SNCC—was hired as the full-time community organizer. The United Presbyterian Church donated money and staff support, in the assignment of Rev. Knotts. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of the city was also on board. Though diverse, like MCOR, the MCO relied on a broad Latino organizational base.

At the first convention, in October 1968, over sixty organizations participated, representing an attendance of between six and seven hundred. Almost immediately, the gathering exposed the tensions within the district. Seemingly a debate on political tactics, the tensions also exposed a generational divide. Established and fairly mainstream organizations sought control over Model Cities funds, a status only assured if the city recognized the MCO as the legitimate representative in the district. To a varied youth contingent empowered by local, radical politics, this suggested a kind of reformism out of step with meaningful change. Groups like the Mission Rebels in Action, for example—an active youth-serving agency—embodied a militant posture. Seeing convention leaders as “sell-outs,” the Rebels took to the stage during the proceedings, seized the microphone, and called the gathering a “farce.” As the San Francisco Chronicle reported, the Rebels then tried to nominate their own platform of leaders.(11) While their tactics upset most in the audience—especially those who knew the group was partially funded by the Equal Opportunity Commission and, hence, part of the aid bureaucracy in the Mission—the group did manage to stall the agenda.

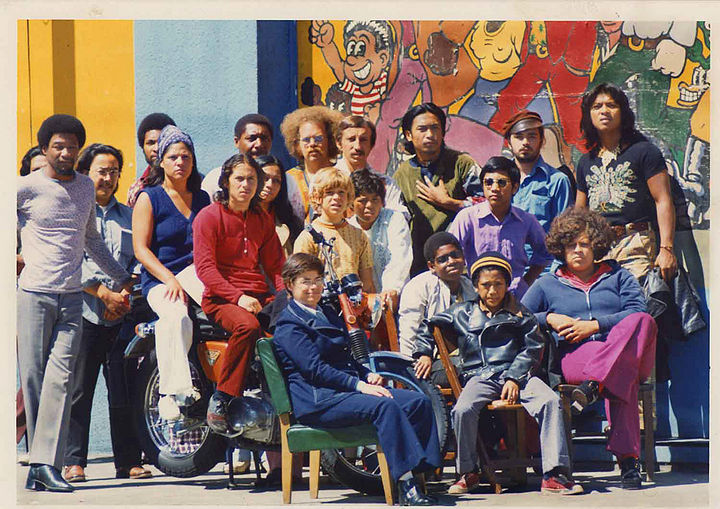

Mission Rebels, c. 1970.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

The convention might have ended in disarray if not for the fortuitous scheduling of keynote speaker Cesar Chavez. Too ill to attend the meeting in person and confined to a hospital bed, Chavez spoke by telephone to the crowd. Quieting the room, Chavez addressed the need for collaboration, inadvertently diffusing the confrontation. Promoting a hybrid ethnic/racial identity infused with class sensibilities, Chavez cautioned against the disabling effects of in-fighting and inaction:

The poor have much in common, common dreams and desires of social justice. The question of goals should not be a problem. The question that kills coalitions is the inability to take that first step in the most common causes, and that is, to determine who is an adversary…La Raza to me was the whole human race.(12)

His plea did not move everyone, as Mission Rebels leader Jesse James took to the microphone once again and proclaimed, “You’re being used again and you don’t even know it.” Accusing MCO leadership of being an inauthentic voice he said, “You’re speaking about community and you don’t even live here.”

Sensing a favorable response to Chavez’s words, Gallegos, moderator of the convention, challenged James to work in the spirit of cooperation. According to local reports, he then chastised the Rebels, saying, “a lot of people out here want a better place to live and you’re not letting them.” In a simple yet moving articulation of common cause and interrelation, he shouted, “All those who care about the Mission, stand up with me!” The convention majority took to their feet, effectively neutralizing the Rebels. They agreed to a compromise, allowing last-minute nominations from the floor. The convention proceeded, electing officers, committees, and bylaws. The organizational platform was tabled to a later meeting.

Unwilling to support the organization, the Mission Rebels remained in small company. Composed primarily of Black youth, with some Latinos, whites, and Samoans, the Rebels could not envision cooperation beyond their own organizational interests. Other constituency groups also disagreed with the MCO vision but stayed and participated. Members of the PL Party, for example, whose Mission Tenants’ Union took decidedly radical stances, objected to the use of conciliatory language in the MCO platform, but worked for compromise. Others who disagreed with the MCO never attended, such as the various homeowners’ associations represented by Bartalini and Hall.

The second half of the convention concluded in November 1968. There, the MCO solidified an organizational structure and established a platform, all while the heated debate reached a provisional consensus. The PL Party continued to voice concern over some of platform resolutions, wanting a more forcefully militant language along with a list of direct issues to focus the MCO’s work. The compromise came with the agreed use of moderate language while adopting the platform of advocating tenants’ rights, reducing unemployment, improving police-community relations, and attending to various education issues. Another disagreement arose over the stance on Model Cities, with the conference leadership advocating a desired participatory stance. Embodying the majority’s agreement, the convention approved a thirteen point platform outlining future Model Cities involvement. The platform included the demand for absolute veto power within the Model Cities program and the right to name two-thirds of the Model Cities Neighborhood Corporation—a 21 member representative body charged with making decisions as demanded by the federal requirement for community participation. Veto power meant the MCO could stop any redevelopment effort it thought adversely affected the community. The demand for two-thirds control meant the ability of the MCO to exert absolute community control over federal funds. As the staff organizer Mike Miller remarked, “The lesson of words vs. real power was yet to be observed.”

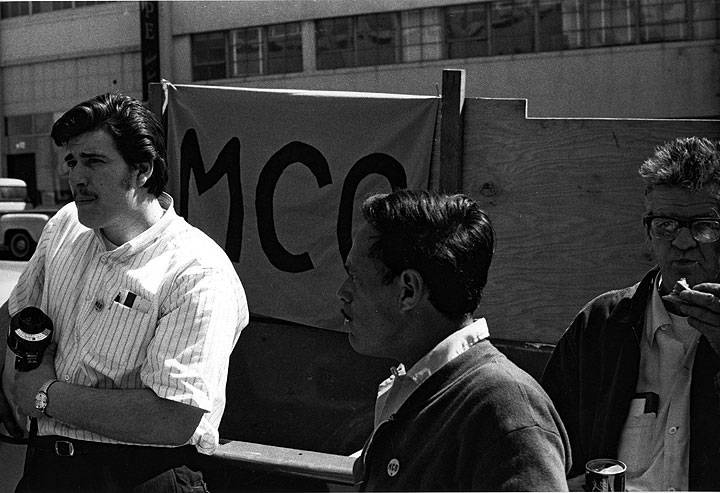

Larry del Carlo (left), Chair of the MCO Jobs and Employment Committee and MCO's 2nd Executive Vice President, with Segundo Lopez, Chair of the MCO phone company negotiating committee.

Photo: Spence Limbocker, courtesy of El Tecolote archives

Even considering the non-participation of certain Mission District interests, the foundational convention of the MCO emboldened the hundreds of participants. With 24 year-old president Martinez at the helm, the Coalition began the work of organizing the community into a mass movement as they sought to meaningfully address community issues and secure local control of Model Cities funds. As Martinez framed it, “We don’t want the money unless we in the Mission have a major voice in how it will be spent.”(13) This commitment to self-determination—described by Martinez as “the opposite of colonialism, which is a system in which someone else says he knows what is best for you and in which he has the power to make you do what he thinks is best for you. We want to decide what is best for us”—came with the participation of now more than 80 local organizations and nearly a thousand residents by its second convention. In less than a year, the MCO would become one of the most effective community coalitions in US history as they got to work addressing neighborhood needs while mobilizing for a head-to-head battle with the Board of Supervisors.

Already the generationally-infused political rift between moderate and radical had dominated the first convention. Illustrative of the local assortment of student, antiwar, and racial movements embodying a high degree of coherence between radical ideologies and their practices, youth increasingly professed a politics only minimally finding purchase within the older generation. Additionally, a far more widespread and long-standing tension was comprised of the rivalries between nationalities, in particular the resentment between an ethnic Mexican population (with longer roots in the city) and a more recently arrived Central American population.

Despite representing roughly forty percent of the Latino population in the City, ethnic Mexicans most often occupied positions of greater visibility and power in local politics, much as they did within the Spanish-speaking cultural milieu of the city. Their dominance helped nurture the integration of new migrants from Latin America, whether they came from Mexico or Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Puerto Rico. The high rates of intermarriage within Spanish-speaking populations is testament to the manner in which a more established Spanish-speaking population could “pull everybody together.” Indeed, as one resident saw it, when members of her family came to the city in the early twentieth century, they came to a “Mexican America.”(14)

By the late 1960s, however, Mexican predominance seemed anachronistic in a Mission District where Salvadoreños and Nicaraguenses combined to form the majority. Prior to the MCO, “it was a fact that Mexican Americans tended to head most of the funded organizations of the Mission.”(15) Accordingly, to remain true to its vision, and to strengthen its coalition by addressing potential weaknesses, the MCO would have to create space in its structure for constituencies whose voice might not be best served by an already recognized organ of the community. The solution came via the MCO Steering Committee—composed of the President, seven Executive Vice Presidents, and the various committee chairs—which met weekly as it took responsibility for implementing the action plan of the Convention. Toward the goals of inclusivity and accountability, the delegates created a Vice Presidential position for each racial/ethnic constituency in the Mission, adding an assortment of VPs to the leadership. Always in the service of coalition, the MCO recognized the value of its diversity, reflected in each of the following positions: Mexican, Nicaraguan, Salvadoran, business, national, youth, senior citizens, block clubs, Mexican-American, Central American, South American, Afro-American, Anglo-American, and Filipino-American.

To outsiders, the identified constituency groups might have seemed redundant. From the perspective of an MCO organizer, the community had a tacit understanding of how it worked:

The understanding was that neither the Nicaraguans nor the Salvadorans would go for the Central American position. Either a Guatemalan or a Honduran would get that. But we couldn’t, we didn’t want to have a Honduran Vice President, or a Guatemalan Vice President because they were small enough in number that the Salvadorans and Nicaraguans said well if you’re going to have a Guatemalan Vice President then we want three…and then…you were going to have a body of sixty or seventy people.(16)

Most significantly, by recognizing the diversity of the Mission, as understood by the residents of the district, the MCO positioned their endeavor to be more than symbolically collective. A blanket assertion of “Latin American-ness” (or latinidad) would ring hollow in a district where the needs of bilingual Mexican Americans differed between those of Central American immigrants, African-American youth, and Filipino families. Though the MCO certainly embodied a kind of latinidad, it did not rely on a limiting definition of who belonged. Unlike a traditional barrio identity, rooted in formal and informal segregation, the MCO’s latinidad relied on the integration of multiple voices, needs, and identities, coalescing in a collective expression of common cause. At their height, a VP position existed to be filled by Puerto Ricans, Pacific Islanders, Cubans, Europeans, Americans, American Indians, Irish Americans, Italian Americans, Colombians, and labor. Even clergy had their own Vice President.

MCO gathering in schoolyard.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

Once a representative structure was solidified, the MCO refocused their energies toward that common cause. Indeed, without tangible results, its representative structure would be meaningless. The MCO committees took on the work, functioning like issue-specific, grassroots campaigns. The committees reflected the collective concerns of the MCO, focused on issues like housing, the police, youth, employment, health, and community maintenance. Comprised, as it was, by an assortment of active and effective community organizations—many of which had experience with these issues—an initial wave of success for the MCO was not surprising. Of course, each concrete victory also fostered increased community support, making MCO membership a source of community pride.

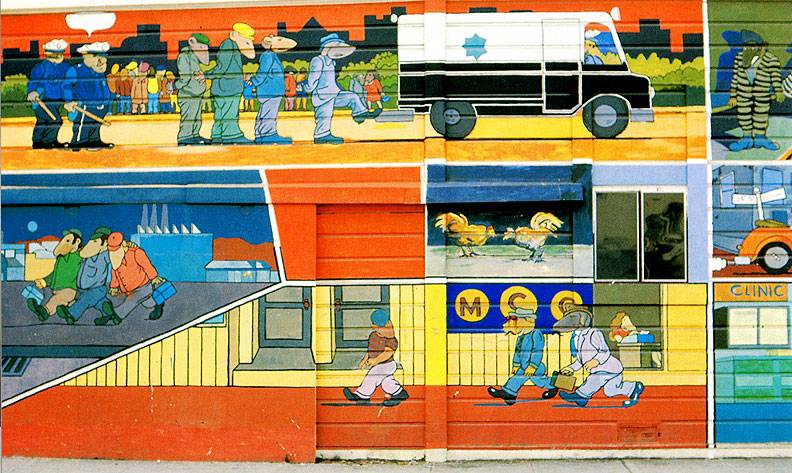

The first mural painted in the Mission in the 1970s revival of the form, by Michael Rios on the side of the MCO building at 23rd and Folsom.

Photo: Tim Drescher

The former MCO offices at the corner of Folsom and 23rd, seen here in 2018, the trees cover the wall that was once graced with Rios's mural.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

MCO mural by Michael Rios at 23rd and Folsom, c. 1977.

Photo: Tim Drescher

Another view, c. 1980.

Photo: Henry Baca

Early MCO campaigns sought to create new playgrounds, ban pawn shops on Mission, and convert an adult theater in the neighborhood into a family theater. In each instance, they sought both cosmetic and systemic change, finding creative ways to make their district more responsive to the needs of its family residents. For example, earlier redevelopment in South of Market area pushed some businesses southward to the Mission. One of those businesses was an adult theater whose presence in the neighborhood would have been unheard of in an earlier generation. After unsuccessful negotiations with the owner, the MCO targeted theater patrons, picketing the theater entrance. They handed out fliers declaring their intention to notify the patrons’ neighborhoods of their patronage. To add a serious tone to their tactic, members followed theatergoers and took down their license numbers. They even had a nun take photos as customers entered, though her camera had no film.

The Housing Committee focused on absentee landlordism and the local stock of deteriorating housing. Involving respected members of the District—like Father Jim Casey, Elba Tuttle, and Luisa Ezquerro—as well as radical groups like the Progressive Labor Party, the Housing Committee sought meaningful mechanisms for tenants to secure and protect their own rights. The committee began organizing residents to negotiate with landlords, peacefully and respectfully informing property owners of the problems tenants faced as well as suggesting solutions. Meeting every Saturday morning, the committee invited landlords by mimicking the process by which a tenant might be evicted—issuing a first, second, and, if needed, third notice—with each succeeding notice communicating a harsher tone:

So you’d get your first notice…very polite, “We would like to meet with you, please call us.” If we don’t hear from you within a week, second notice, “Please call us within three days.” If you don’t call us within three days, third notice, “If we don’t hear from you within forty-eight hours, we will take further appropriate action.” It didn’t say what the further appropriate action was.(17)

When a landlord appeared, the committee tried to negotiate a solution. If the landlord ignored them, or failed to appear at an agreed time, the MCO traveled to the landlord’s home or business and picketed. Seeing the utility of social coercion, they distributed fliers in these neighborhoods informing locals that an abusive, absentee landlord lived among them. The combined tactics produced results; in their second year, the MCO served as the official dispute agent for 23 district buildings, each with their own grievance procedures and maintenance agreements. Sometimes they even helped landlords deal with irresponsible tenants.

The Employment Committee was widely regarded as the MCO’s most successful, in particular when measured by the membership growth they incited. In their second year, they developed a youth employment campaign. They secured a meeting with Wonder Bread and Hostess Bakery, intending to secure summer jobs. When the meeting was cancelled, a dozen members of the committee staged a sit-in at the office of the manager they had been scheduled to meet, forcing a new meeting. When negotiations were completed the MCO secured about a dozen positions—each for a third of the summer—and the power to place local youth in the positions. But who would get the jobs? Internal committee deliberations stalled until a young woman, silent up to that point, asked, “Why don’t we give the jobs to the people who worked to get them?” The result was the MCO Point System, where members earned points through their support of the MCO. Points could be earned by attending meetings, participating in actions, or other forms of support. Then, as jobs came in, they were awarded to the people with the most points, who could take it or pass it along. Within weeks, youth participation rose to more than one hundred. By fall, with full-time jobs the goal, regular weekly participation grew ballooned to 300.

Success propelled growth in membership, adding to the perceived legitimacy of MCO within the City and framing a stronger position for negotiating a Model Cities agreement. Knowing whoever controlled the Model Cities Neighborhood Corporation, controlled the future of the Mission, Martinez sought to convince City Hall that the MCO was the only representative body who could speak for the diverse community. This would compel their involvement, since the legislation mandated “maximum feasible participation” with the goal of assuring “broad-based community support.” After six months of negotiations with the mayor, the parties reached an agreement in May 1969 giving functional control of the Corporation to the MCO on its own terms. While the MCO sacrificed their demand for veto power, the compromise required the mayor to appoint 14 of the 21 board members from a list provided by the MCO. Additionally, the MCO could create a committee to review proposals for funds, evaluate the work of the corporation, and recall board members they originally nominated.(18)

The agreement now required the support of the Board of Supervisors. There, the MCO faced opponents seeking to portray them as a non-representative body. The first step was the Board’s Planning and Development Committee, which met on September 16—Mexican Independence Day. The MCO mobilized more than five hundred community members to attend, using the public testimony session to present 75, two-minute speeches in support of the agreement with City Hall. The local press described the MCO and their “orderly, disciplined show of strength” in contrast to the unorganized opposition of no more than 150, people who called the agreement an “unholy alliance” and accused one Supervisor of being a “political prostitute.”(19) The most organized opposition group called themselves the San Francisco Fairness League, led by Mary Hall. To express their united front, they presented the committee with a petition signed by more than 100 locals, most self-identified as homeowners. The MCO did the same, but with a stack of more than 2,500 signatures of propertied and non-propertied alike.(20) The Planning and Development Committee voted to approve the agreement, forwarding the issue to the full Board.

Maintaining their visible community support through multiple mass actions in the fall, the MCO worked toward assuring formal approval at the full Board of Supervisors meeting on December 1, 1969. At that meeting, the Board had to vote on both the proposed bylaws for the Model Cities Corporation as well as a request for federal funds to “plan and develop a comprehensive City Demonstration Program in the Mission area.” Citing “doubts as to whether or not the Mission Coalition represents the people of the Mission District,” some supervisors sided with the opposition. The majority sided with the MCO, with one supervisor calling it “a significant step forward for putting the decision-making power in the hands of the people of the neighborhoods.” The twin resolutions passed by a vote of 7-to-4.(21)

The Model Cities struggle continued when the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) vetoed the approved bylaws as giving too much power to the MCO. Beyond calling the agreement a “conspiracy between Mayor Alioto, the local Offices of Economic Opportunity and labor,” the San Francisco Fairness League missed their opportunity to exploit the federal decision.(22) Mayor Alioto himself sought to undermine the MCO’s position, assigning a staff member to encourage some of his local allies to pull out of the MCO, but City Hall’s political networks were no match for the MCO’s service record. At St. Peter’s Catholic Church, Father Jim Casey refused to cooperate, expressing his support for the MCO’s housing goals. Enjoying the improved commercial climate as a result of the MCO’s efforts to close pawnshops and the Crown Theater, the Mission Merchants’ Association also refused.

As the MCO and Alioto negotiated a new deal in the spring of 1970, the Coalition sought to fortify their representational status. Martinez invited the mayor to take a walking tour of the district to view their efforts firsthand. Suggestive of their ability to work within the parameters of traditional politics, the MCO also invited the Board of Supervisors, State Assemblymen, and a representative from Governor Reagan’s office. When Alioto cancelled, the MCO conducted the tour for the other dignitaries, to favorable press coverage. The mayor’s absence stood in contrast to the attendance of key Democratic and Republican leaders, including an aide from the head of the State’s Model Cities Liaison Group, who declared, “The governor has heard of radical elements in the coalition, but the people you see aren’t that at all.”(23) Soon thereafter, Alioto reached an agreement with the MCO, which the Supervisors ratified, 6-to-5.

The second MCO convention came in the midst of their Model Cities campaign. The celebratory mood reflected their continuing success, leading Martinez to reflect on the passage of only one year. “I can remember when I first chaired MCO meetings that all the faces were familiar,” he wrote in a memo, “This has changed a lot.” Among the changes was a growing consensus on the political divisions of the previous convention. As Martinez noted, the PL Party and other radicals pulled out as “the valid issues that they had monopolized in the past are now being worked on by MCO without the Mao Tse-tung rhetoric.”(24)

MCO annual convention, 1972.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

In the ensuing years, the MCO struggled under the bureaucratic weight of its new responsibilities regarding the federal funds of Model Cities. Internal political disputes—reflected in Martinez’ successful attempt to amending bylaws allowing for a third term as president—incited further withdrawals from the Coalition. By 1973, the MCO maintained control over the Corporation but engaged in fewer actions as a coalition, focusing attention on the distribution of federal funds. As one activist put it, “the MCO [lost] opportunities to develop a broad-based CDC [Community Development Corporation] because of community politics including a fight for power which did not exist, and the co-optation of activists by City Hall by putting them on the Model Cities payroll.”25 Often derided as “poverty pimps,” playing the role of bureaucratic agent held less appeal than community organizer.

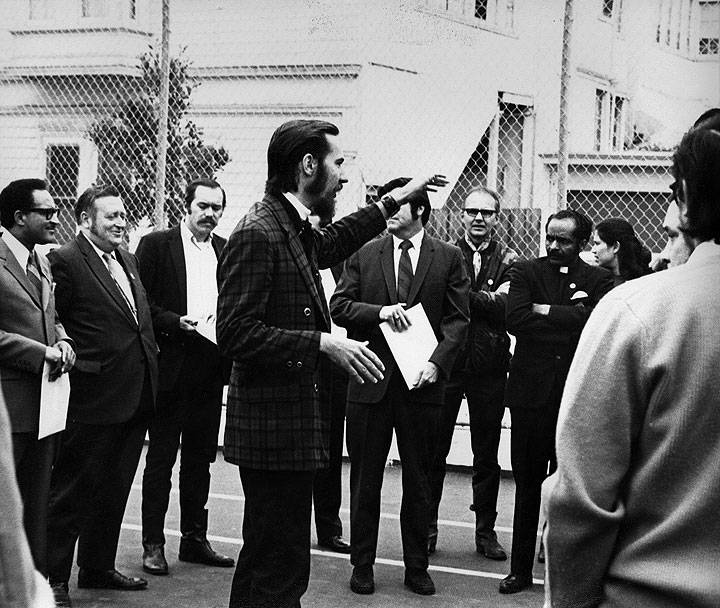

Assemblyman Willie Brown meets with MCO activists in Mission, 1972.

Photo: El Tecolote archives

But the MCO was hardly a failure. At its height, it successfully involved more than twelve thousand Mission District residents in the bettering of their own community and the planning of the district’s future. Transforming a fractious community divided by class, generational, and ethnic conflicts, the MCO made major inroads in creating an environment where all its members could begin to understand their common interests as well as realize the power of their common efforts. For the Latin American, Spanish-speaking majority of the Inner Mission, the MCO orchestrated their emergence as a visible constituency, the group most associated with the post-war Mission. Buttressed by their demographic predominance in the district, their recognition as a collective entity emerged simultaneously with their organizational work nurturing this common identity. This collective identity coalesced within their movement, balanced on the vision of a common past while respectful of its location in a crucible of diversity. This is notable, for in an era when Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest came together in multiple forms of political action, usually under a Mexican-American based form of cultural nationalism known as chicanismo, the MCO exemplified a population predominantly of Latin American descent uniting under the umbrella of a multiracial and multiethnic coalition. Such efforts relied upon their ability to express shared identities based upon class, race, generation, and national origin, but they also required the recognition of difference. In the case of the MCO, this found organized expression in a hybrid form latinidad, most often under the term Raza, a collective identity encompassing difference while suggesting similitude.

While it suffered as a bureaucracy, the MCO achieved lasting victories as a coalition movement. The political culture of self-determination and collaboration remain in the district today, as does the dignity that comes with a meaningful, grassroots movement. After all, as the MCO lead organizer described it, their greatest success was the dignity gained:

When we came out of the phone company meeting—we got an agreement for, I think on an annual basis it was in the hundreds of jobs—and the guy who was the chairman of that negotiating committee was Segundo Lopez…So we’re walking out of the front door, I turn and say “Segundo wasn’t that fantastic?” And I’m talking about the jobs. He looks at me and says “Yeah, Mike, you know that vice president called me Mister Lopez.”(26)

Segundo Lopez was not alone in his newfound sense of pride. In countless other situations, thousands of residents encountered the same transformations within themselves. As they looked toward their future within the City, with increased expectations of the role they could play in shaping of their destinies, succeeding generations of Latino residents of San Francisco would also benefit from the work of the MCO.

by Tomas Sandoval, from his essay "All Those Who Care About the Mission, Stand Up With Me!," in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.

Notes

Thanks to Mike Miller for giving this essay a close read and making many helpful corrections and suggestions. For a much longer and more in-depth insider’s view of the MCO history, check out his book A Community Organizer’s Tale (Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA: 2009).

1. Ben Martinez, “The State of the Community” (address, Second Annual Convention of the MCO, October 18, 1969).

2. Manuel Castells, The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-Cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements (University of California Press, 1983), 106.

3. William V. Flores and Rina Benmayor, eds., Latino Cultural Citizenship: Claiming Identity, Space, and Rights (Beacon Press, 1997), 13.

4. Mike Miller, “An Organizer’s Tale” (unpublished, 1974), 11.

5. David Braaten, “A Place of Many Voices.” May 1, 1962; “Signs of a Renaissance.” May 4, 1962; and “Slow Decay—and the Problem of Indifference.” May 5, 1962. All San Francisco Chronicle.

6. Fr. James Hagan, interview by Jeffery Burns, July 5, 1989, Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco.

7. San Francisco Department of Planning, San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, A Survey and Planning Application for the Mission Street Survey Area (May 1966), File 148-66-3, Archives of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, San Bruno, CA.

8. San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Journal of Proceedings (December 19, 1966), 61:53, 951.

9. Thomas F. Jackson, “The State, the Movement, and the Urban Poor: The War on Poverty and Political Mobilization in the 1960s,” in The “Underclass” Debate: Views From History, ed. Michael B. Katz (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 412.

10. Miller, “Organizer’s Tale,” 25.

11. “Mission Coalition’s Fighting Mad Start,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 5, 1968.

12. “Cesar Chavez habla: his speech to the Coalition Convention,” La Nueva Mission 2, no.10 (November 1968): 7.

13. “Mission Group’s Tough Demands,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 4, 1968.

14. Helen Lara Cea, interview with author, October 4, 2001.

15. Miller, “Organizer’s Tale,” 37.

16. Mike Miller, interview with author, October 4, 2000.

17. Ibid.

18. Scott Blakey, “Mission Plan Clears One Hurdle,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 10, 1969.

19. Russ Cone, “Stormy Hearing on Mission Model Cities,” San Francisco Examiner, September 17, 1969.

20. Petitions of the San Francisco Fairness League and the Mission Coalition Organization, File 401-69-1, Archives of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, San Bruno, CA.

21. San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Res. 838-69 and Res. 377-68, Journal of Proceedings, (December 1, 1969), 64:48, 974.

22. “Opposition to Mission Coalition,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 27, 1969.

23. Joel Tlumak, “MCO Impresses Top Reagan Aide,” San Francisco Examiner, July 19, 1970.

24. Memo from Ben Martinez to Lou White, November 24, 1969, located in MMA.

25. Leandro P. Soto, “Community Economic Development: More Than Hope for the Poor” (San Francisco, 1979), 8-9.

26. Miller, interview.

Find the book at City Lights!

Find the book at City Lights!