Little House on Russian Hill

Historical Essay

by Holly Erickson

Little House on Russian Hill—When Laura Ingalls Wilder lived in a Willis Polk Home during the Pan-Pacific International Exposition

Happy New Year Card, 1915, from the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, seen here from Russian Hill.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.04187

Nine decades worth of children have adored the “Little House” books. When the series of books left off, pioneer Laura was left on the unforgiving prairie subject to the biblical tragedies of fire, flood, famine, and fever—not to mention blizzards and locusts. Laura’s sister Mary had been blinded by measles. Diphtheria lamed her husband Almanzo. One of Laura’s babies died, and she only had one other. With all of its hardship Laura’s arduous life was typical for the pioneer experience. But her entire life was not beset by calamity on the shores of Silver Lake. Even before she became a world-famous author Wilder lived a happy, healthy, and prosperous life and she spent some of it right here in San Francisco.

Rose Wilder Lane, Laura’s only daughter may have been the twentieth century’s Nelly Bly (“intrepid girl journalist” who, before air travel, made it around the world in 80 days). A writer for The Bulletin, one of San Francisco’s many thriving newspapers at that time, Wilder had recently strapped herself to the bi-plane of world-renowned aviator Lincoln Beachey and glided over San Francisco Bay. She and her husband Gillette lived in the fifteen–year-old Willis Polk brown shingle duplex at 1018 Vallejo atop Russian Hill. And this is where, in 1915, Laura Ingalls Wilder came to live with her daughter and visit the Pan-Pacific International Exposition.

The Panama-Pacific International Exhibition was reason enough for Laura Wilder to climb aboard a train and travel from Rocky Ridge, her farm in Missouri, to San Francisco. Laura acted as her local newspaper’s Martha Stewart, writing recipes and farmhouse advice. She intended to write about the Exposition for the folks back home.

For Laura the trip by train was a journey of a few days. But heavy goods from Europe and the Far East had to come shipboard on the long route around the horn of South America. When the Panama Canal was completed this trip could eliminate South America altogether, saving huge amounts of time and money. The completion of the canal was definitely something to celebrate. Furthermore, San Francisco had been devastated by fire and earthquake just nine years before the 1915 exposition. The City was eager to show off and celebrate how it had rebuilt.

At the time of the Exhibition, World War One was entering its second year. Wealthy Americans could no longer enjoy their Grand Tours of Europe. The majority of Americans, like Laura and Almanzo Wilder, farmed for a living. Unable to leave crops and animals for any length of time, farmers couldn’t go on vacations of any length. But this exhibition with its international architecture, paintings, sculpture, dance, foods, costumes, and culture could give Americans a taste of abroad. Marin County dairy farmers, Petaluma chicken farmers, Santa Clara fruit growers, as well as city dwellers could take the train, ferry, or the streetcar to the Worlds’ Fair. In addition to international culture, the Fair exhibited the latest technology from airplanes to farm machinery. The Fair opened in February of 1915 closing in December of that year. 20,000,000 visitors enjoyed its offerings along with Laura. And she may have rubbed elbows with the like of Buffalo Bill, Charlie Chaplin, FDR, Teddy Roosevelt, Helen Keller, and Thomas Edison as they too enjoyed the sights.

Lincoln Beachey, the daredevil aviator, looped his last loop-the-loop March 24th, 1915 in a show exhibition at the Fair. After his plane plummeted into the Bay that day, he drowned. You can see the Lincoln Beachey Memorial Placard at the Marina Seawall between Marina Green and Crissy Field. Aviator Art Smith took over the airplane tricks and Rose Wilder later wrote her first book about him.

Roger MacBride, a close friend of Rose Wilder and her literary executor, compiled Laura’s letters home during this time in “West From Home” Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder—San Francisco 1915. From the letters she wrote to her husband Almanzo, who was holding down the farm back home during her trip, we read her reactions to San Francisco and its sights.

Arriving in August of 1915, Laura Ingalls Wilder was dazzled by the City. Viewing the Pacific Ocean for the first time she wrote to Almanzo,” To say it is beautiful does not express it. It is simply beyond words. The water is such a deep, wonderful blue and the sound of the waves breaking on the beach and their whisper as they flow back is something to dream about.“ She later writes,” You know I have never cared for cities, but San Francisco is simply the most beautiful thing…. It’s like a fairyland.”

Rose and Laura put on their heavy coats (it was August after all) and sat on a stone curb near the house to view the fireworks put on by the PPIE. “The white Tower of Jewels is in sight from there. The jewels strung around it glitter and shine in beautiful colors. The jewels are from Austria and cost ninety cents each!” she writes. (At the time you could feed a family of four at a nice restaurant for that amount.)

Once Laura attends the fair on September 4th 1915, she proclaims in her letter home, “ One simply gets satiated with the beauty. There is so much beauty that it is overwhelming.” She loves Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts (the only remaining vestige of the Fair). She was probably unaware that the architect who built the house where Rose lived (which also housed Katherine Anne Porter) was the chief architect of the entire exhibition.

Laura witnesses “friendly and good-natured “ Navajos making baskets, Japanese sumo wrestlers, and Samoan dancers, who end their performance with a rendition of “ It’s A Long, Long Way to Tipperary”, which Laura finds unsettling.

She feels the “Statue of the Pioneer Mother” is very “true in detail.” She should know. Created by Charles Grafly this statue stands today in Golden Gate Park near the Log Cabin.

When Rose is working on a newspaper article Laura enjoys ”loafing” while nice and warm indoors. “We have had the thickest fog for several days…We cannot see the Bay at all nor any part of San Francisco except the few close houses on Russian Hill. The foghorns sound so mournful and distressed, like lost souls calling to each other through the void, (Of course no one has ever heard a lost soul calling, but that’s the way it sounds). It looks as if Russian Hill were afloat in a gray sea and Rose and I have taken the fancy that it is loosened from the rest of the land and floating across the sea to Japan,” writes Laura.

Rose holds a tea party to introduce her women friends to her mother. One of these women is Berta, who then illustrates some of Laura’s poems and suggests she write her pioneer story, previously meant for adults, for children. When Berta moves into rooms at 1637 Taylor, Laura enjoys visiting her there, partially because she loves the stone wall and stone steps that she must climb to get to her young friend.

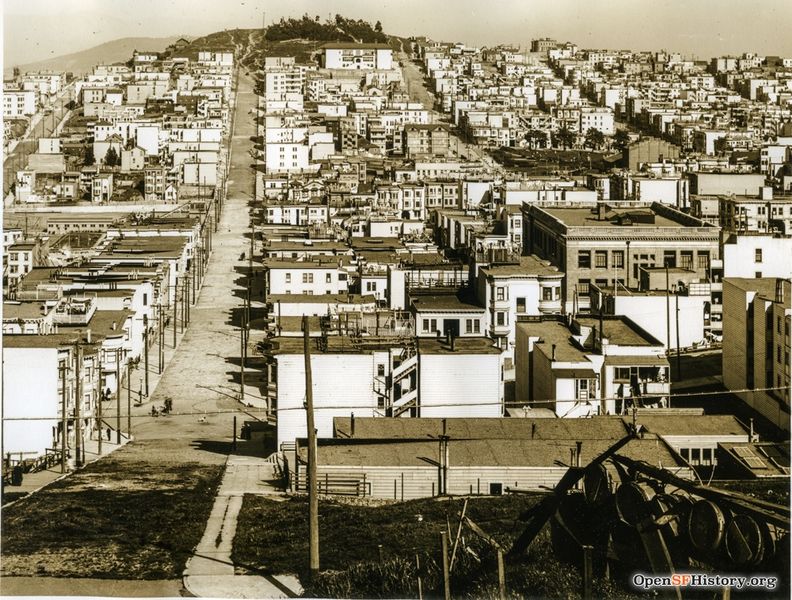

View from Russian Hill towards PPIE Fair, 1915.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org wnp14.4511

The exhibition is not the only sight worth seeing in San Francisco. Laura enjoys all the tourist spots that people flock to today.

“We went to an Italian restaurant in Little Italy, the part of town where the Italians live. It was a funny little restaurant where we could sit and watch the cooking done and the proprietor himself cooked or waited or did whatever was necessary. His wife waited on the tables… The room was full of people eating and not a word of English was spoken except by Rose and myself, except when the proprietor struggled to take our order. Everyone was talking and a group of men got excited and talked loudly at each other. I’m sure they were talking about the war. The food was fine, though I could not tell you the name of it, and it was all very interesting indeed,” she tells Almanzo in a letter.

View east from Greenwich and Leavenworth in 1911, similar to view from the house Wilder stayed in, overlooking North Beach.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.3799

While Laura may have had enough of Prairie Schooners, she seems to have been enchanted with actual boats, which she mentions time and again in her letters home to Almanzo. “We walked to the top of Telegraph Hill. To reach it one goes through the Italian tenement district where the Italian fishermen live. There were fourteen sailing ships anchored in sight and three big ferry ships.”

Tea in Chinatown follows a walk through fish markets and shops featuring carvings in ivory. “The streets are full of the Chinese people of course. A good many of them are wearing American dress and are very nice-looking. Some still wear the Chinese costume.”

She visits the Presidio where the enlisted men still lived in tents and gazes at Alcatraz, which was then a military prison. “The fog horn on Alcatraz’s crying out at regular intervals. It must be that the fog is getting thick. Every few minutes I hear the bellow of a steamer’s whistle, as it comes in or meets or passes another boat,” and "The foghorn on Alcatraz is the most lonesome sound I ever heard and I don’t see how prisoners on the island stand it.”

While on another walk, mother and daughter come across some Italian fisherman mending their nets who guide the pair to Fisherman's Wharf. “ Everyone was so pleasant and gentlemanly,” Laura finds. And she sees plenty of fish.” Some were great salmon that would weigh from thirty to sixty pounds. We could buy one weighing about twenty-five pounds for sixty cents. “ (That amount of salmon would cost about $450.00 today.) They peek in at the Cannery where some three hundred Italian women canned California fruit. Laura hadn’t trusted factory-canned fruit before, but finds the premises perfectly sanitary. They visited Sausalito, by ferry of course, throwing bread to the gulls, Mission Dolores, Butcher Town (between Islais Creek and Evans Avenue in the Bayview where the slaughterhouses served the City) and China Basin.

While revisiting the Fair, Laura is impressed seeing the Carnation Milk exhibit where she learns about condensed milk and is amazed to see a milking machine …” And it milked them clean and the cows did not seem to object!” she writes to her farmer husband who was probably as amazed as she. She is also impressed with the seeded raisins on offer. They had always had to seed their own raisins before this latest development.

Laura eats at every international booth at the Fair, chatting with the workers and getting recipes for croissants, Chinese almond cookies, tamales, tagliarini, German honey cake and the like, which she later publishes in her hometown newspaper and appear in the book “West From Home”. Rose had hoped to convince her mother to buy a chicken farm in California, but Laura feels homesick, finds it too hot outside of San Francisco, and her research on egg prices does not convince her that the project would be viable. Thus, the Little Hen House books never come to be. Rose Wilder Lane did not stay at the sumptuously situated brown shingle on the top of Russian Hill for long. She split from her husband, wrote her first of many books, moved back in with her parents from time to time, travelled the world (finding Albania particularly to her liking), and became one of the founders of the American Libertarian party.

Twenty years after her stay in San Francisco, Laura Ingalls Wilder became a household name in the 1930s with the publication of her “Little House” series. The shy, ill-nourished, tragedy-prone young pioneer had became an intelligent, curious, open-minded, writer whose experience had been broadened by her time on Russian hill. She and Almanzo prospered, living happily at Rocky Ridge Farm into their nineties.