George Gordon

Historical Essay

by Libby Ingalls

George Gordon

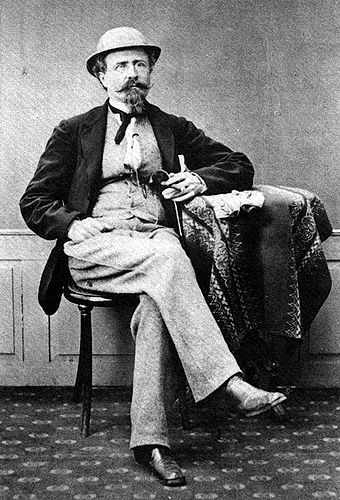

George Gordon (1818-1869) was a flamboyant speculator and entrepreneur of the early Gold Rush days. Astute businessman and relentless schemer, he had an eye for opportunities and a knack for profitmaking, while always seeking the greater good for San Francisco. In an era of lawlessness and greed, he was remarkably honest, civic-minded and public-spirited. Upon his death, the many eulogies praised him for his major contributions to the look and economy of San Francisco.

Born in London, Gordon was already a free-spirited entrepreneur by his mid-twenties, listed in registries as a broker of tea and guano. In 1847, he emigrated to New York, changed his name from George Cummings to George Gordon, and listed himself as an engineer, real estate broker, chemist, geologist, and contractor, with no mention of tea. One of many mysteries surrounding Gordon is why he emigrated and changed his name. Perhaps, it is thought, he had been smuggling tea in London.

On Dec. 5, 1848 President Polk confirmed rumors of the discovery of gold in California. Within two weeks, Gordon had founded "Gordon’s California Association," one of 47 such companies organized in New York to take people to the gold fields, providing passage, provisions and mining machinery. Most such companies, Gordon’s included, had no idea what they were getting into. Consequently they packed inadequate provisions and useless equipment, and broke up before or upon arrival in San Francisco.

Gordon sent two ships, the first by Cape Horn, the second to Nicaragua, crossing by land and picking up another ship on the Pacific coast. Both ran out of provisions, were delayed by many weeks, and came near mutiny. Gordon, with his wife Elizabeth and young daughter Nellie, went on the second ship via Nicaragua. Taking eight months under atrocious conditions, instead of the advertised comfortable 60 days, it is remarkable he wasn’t thrown overboard. Quite the contrary, four years later he held a reunion and 100 people came. The reunions continued for the next 34 years.

This voyage was also the start of his fortune in California, for while stuck in Nicaragua Gordon purchased as much wood as he could, suspecting there would be great demand for building material in San Francisco. His risk paid off, and upon arriving in San Francisco he made several thousand dollars to start his new life. With his unrelenting energy and risk-taking speculation, he viewed the bustling tent city in the San Francisco sand dunes as his gold field, and settled in.

Gordon continued to deal in lumber, began wharf building, and then started selling prefabricated buildings, including a church that would seat 1,100 people and a 32-room hotel. In 1850, Gordon built Harrison Wharf, extending over 1,000 feet into the Bay through the shallow Yerba Buena Cove so ships could be unloaded directly.

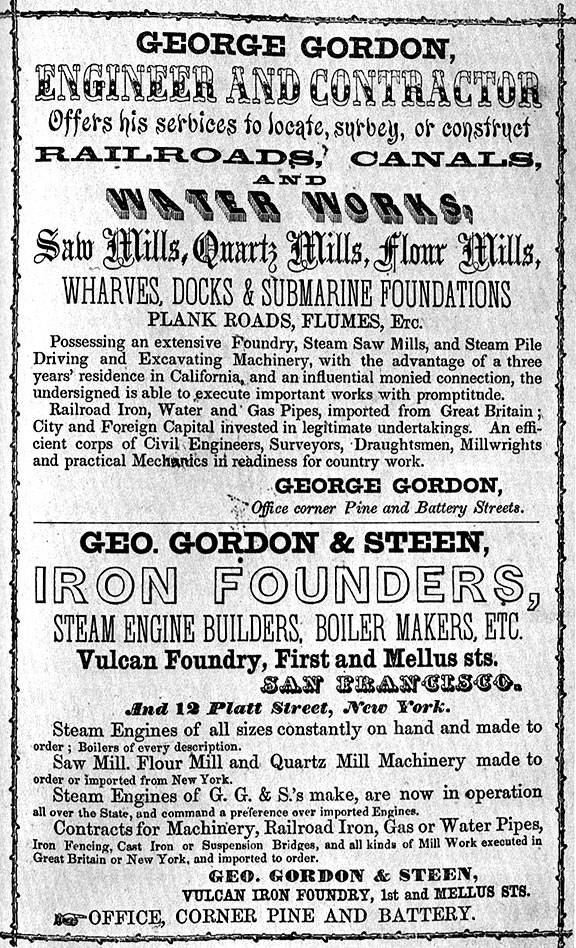

As the city of wood grew, so did the incidence of fire, with six devastating ones from December 1849 to June 1851. While these kept up the demand for lumber, they also got Gordon thinking about a new enterprise: fireproof buildings. He began importing pre-fabricated iron houses from London and the East Coast, and in 1851 just after the 6th fire, he built “George Gordon’s Block of Iron Stores,” a city block of 2-story iron buildings, fireproof, complete with water tank and watchman. Seeing iron as the way of the future, he sold his lumber business, and in 1852 with Edward Steen, engineer and inventor, incorporated the Vulcan Iron Works, grandiose and staggering in its range of activities and ambition. They offered, or built, iron doors, shutters, mill and farm machinery, steam engines, bridges, bank vaults, and more, seemingly anything needed.

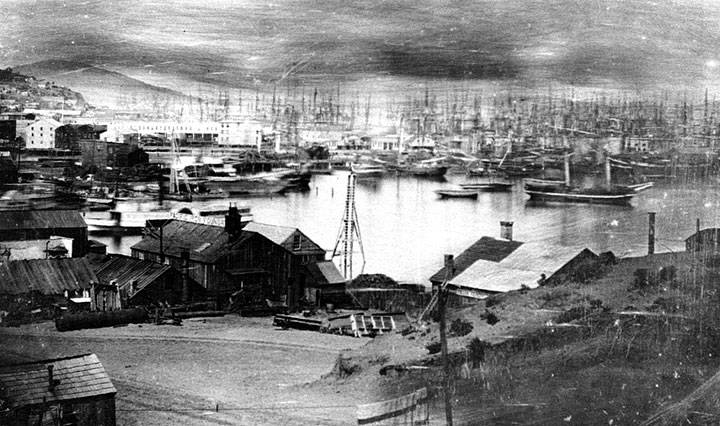

1851 view of Yerba Buena Cove from Rincon Hill, with the Vulcan Foundry, founded by George Gordon, at lower left.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

At the same time the city topography was changing by leveling hills and filling wetlands. New streets were constructed, with the result that people wanted to move their houses. This time, Gordon’s partner Edward Steen answered the call and developed the first patent for raising houses using a hydraulic press, advertised as capable of lifting 4,000 -5,000 tons.

South Park, 1865: looking northeast from 3rd Street (up Rincon Hill)

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library (AAA-7039)

Early in 1852 George Gordon started buying property south of Market, outside the business district, an investment that would lead to the development of South Park. By 1854 he had acquired 12 acres on the south side of Rincon Hill, enough for his vision of an elegant residential development of 68 building lots. He printed an 8-page prospectus of his plan for “ornamental grounds and building lots on the plan of the London Squares, Ovals and Crescents, or of St. John’s Park or Union Square in New York.” Houses would be of brick or stone, designed by Gordon H. Goddard, Esq., architect of the Holland Park Estate in the West End of London. The development was to be two crescents divided by Center Street, most houses having two stories on a British design with English-style basements for a dining room, kitchen, servant’s quarters and pantries. Stables and coachman’s quarters were in separate buildings in the rear, and an oval ornamental garden in the center surrounded by an elegant iron fence.

By the end of 1854, 17 stately residences were completed, praised in a San Francisco Herald editorial for their handsome improvement to the city. Gordon continued to sell lots in spite of an economic depression from decreasing yields of gold. Throughout the later1850s and 1860s Rincon Hill and South Park were the stylish area of the city, center of fashion and address of the social elite, as well as the scions of business, banking, politics, mining, and railway and steamships companies.

The particular appeal of South Park was that it was strictly residential, free of saloons and gambling halls, the houses were fire proof, and it provided an attractive neighborly community.

All changed in 1869 when Second Street was cut, making the area more accessible to less affluent people and altering the character. The invention of the cable car in 1873 allowed easy access to Nob Hill, and the fashionable South Park dwellers began moving north.

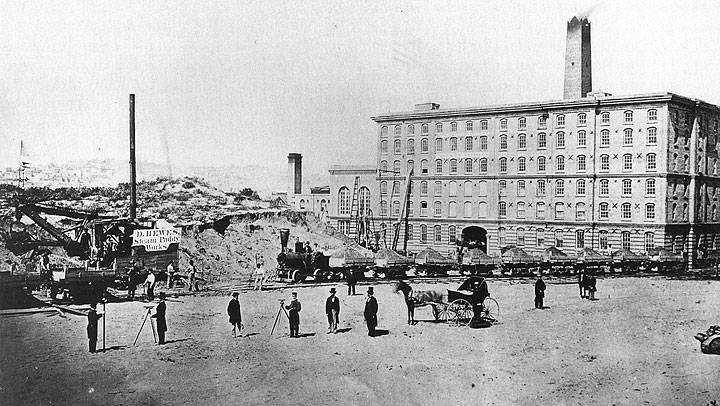

The "Hewes Steam Paddy Works" at left side of photo shows how the sand dunes that once dominated the South of Market were leveled, filling in the once ubiquitous fresh water ponds. 'Paddy' refers derogatorily to the Irish laborers who were replaced by the steam shovel. The building is Gordon's Sugar Works at 8th and Harrison.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Meanwhile, Gordon had already started losing interest, perhaps realizing it was not going to bring great wealth, and began thinking about his next great venture. San Francisco of the 1850s was the perfect place for a dreamer such as Gordon, itself a place of grandiose vision. So in 1856 Gordon decided to establish the first sugar refinery in California, one capable of supplying all the needs of the Pacific Coast. With capital obtained from New York, he built a factory of brick, five stories high, on the NW corner of Harrison and Price (now Eighth St.). The machinery was sent from the East Coast, and the raw sugar from Manila and Batavia (Java). By February 1857 the refinery was in full operation providing high quality sugar. Soon he was importing raw sugar from Siam, China, Formosa, and Mexico to meet the demand. By 1860 the San Francisco Sugar Refinery was one of the city’s most important businesses.

With the refinery flourishing, the early 1860s was a period of affluence for Gordon. On trips to New York for refinery business he purchased fine clothing, jewelry and glassware. Receipts from San Francisco show purchases of furniture, carpets, fine wine, saddles and books, among other luxury items. While obviously enjoying the high life, he still rose above it, as both a civic and philanthropic leader, with memberships in the YMCA, Chamber of Commerce, and St. Andrew’s Society, as well as leadership roles on numerous committees for balls and benefits for social causes.

In 1861 Congress enacted an income tax, openly revealing Gordon’s place among the wealthy elite. As such, he set out to create an elaborate country estate, selecting Santa Clara for its convenience to the railway line from San Francisco. He purchased 572 acres, designed the house himself, and assumed a new persona of English gentleman farmer. He named the estate Mayfield Grange, and moved there permanently in 1864. His sumptuous house parties were the talk of San Francisco.

In addition to his domestic, entrepreneurial and civic activities, Gordon was also an inveterate writer of pamphlets and letters-to-the-editor. Subjects included safety at sea, value of immigration, advantages of an overland mail route, the inequality of taxation, the validity of titles to mining rights, and pleas for peace before the Civil War. Two particularly controversial issues he wrote strongly against were the Second Vigilance Committee, and the Bulkhead Project, in which a private company proposed building a sea wall in exchange for exclusive rights of wharf usage and anchorage. In his stance against the Second Vigilance Committee in 1856, he was not afraid to publicize his position, distinctly unpopular at the time, writing a long, well balanced letter to the Chronicle, focusing on the sacredness of the Constitution and importance of rule by law. His patriotism and belief in the US government were steadfast; yet he never became a US citizen.

Gordon’s health began to fail during a trip to Europe in 1865-1867 while trying (unsuccessfully) to obtain secretive information on European methods of sugar refining. He had a short-lived recovery back in San Francisco. But then in February 1869, his beloved daughter Nellie eloped with a man Gordon despised, and three months later he died, of a broken heart, they said.

The obituaries and eulogies for George Gordon were prodigious, and the praise overwhelming. They extolled his wisdom, business acumen, civic leadership, and public spirit. He was an exceptional person at a time of single-minded moneymaking, in his commitment to the public good and highest civic ideals.

Gordon’s death marked the beginning of the rapid downfall of his family and empire. Nellie separated from her husband in 1872, then died of typhoid fever two years later. His wife Elizabeth died soon thereafter at age 49. The estate became embroiled in lawsuits and vague codicils, but most went to Elizabeth’s brother John Clark, who himself died five years later. Clark’s widow sold Mayfield Grange to Gov. Leland Stanford, who renamed it Palo Alto. He increased the size of the estate, and went on to construct the University, opened in 1891, in memory of his deceased son. The house was badly damaged in the earthquake of 1906, was repaired, and later served as the Stanford Children’s Convalescent Hospital. It was finally demolished in disrepair in 1965. The sugar refinery continued for a few years, gradually declining until 1874 when Claus Spreckels’ California Sugar Refinery gained the monopoly of the market. South Park became a working class neighborhood as apartment buildings replaced the mansions and townhouses. It burned in the 1906 fire, was rebuilt around the central oval park, and is today once again thriving as the home to design and technology companies.

Based on source: A San Francisco Scandal: The California of George Gordon, Forty-niner, Pioneer, and builder of South Park in San Francisco, by Albert Shumate