Bechtel Corporation

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson, November 2016

The railcar that is mythologized as the point of origin for the Bechtel Corporation, parked permanently in front of their corporate headquarters on Beale Street in San Francisco.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Bechtel Corporation is one of the most closely-guarded, secretive multinational companies in the world. It is headquartered in downtown San Francisco. Unbeknownst to most people, Bechtel is embedded deeply in the CIA, the Defense Department, the Department of Energy, and has shaped the infrastructure of California and the Bay Area going back to before WWII. You never see their name, but they designed BART, they are running the recently privatized labs at Livermore and Los Alamos that design, test, and maintain nuclear bombs, they built many of PG&E’s hydroelectric dams and got their start as part of a consortium paid by the federal government to build Boulder Dam (now known as Hoover Dam) on the Colorado River.

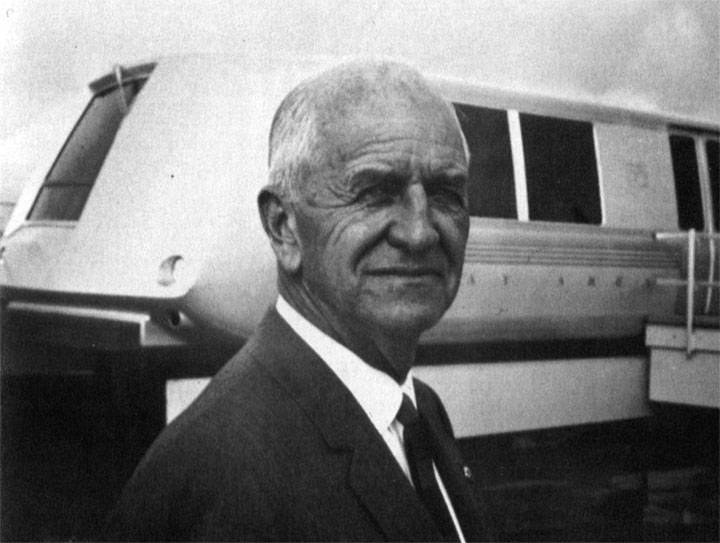

Steve Bechtel, Sr., in front of a BART car in the mid-1970s.

Photo: Bechtel Corporation

A great many of the secret and not-so-secret wars pursued by the U.S. government, from Vietnam to the Middle East, have had Bechtel’s interests at their heart. Though privately owned by the Bechtel family, now run by a 4th generation, the company is so fully embedded within the “deep state” that runs the U.S. military-industrial complex, that it’s difficult to know the boundary between the company’s interests and the policies pursued by the U.S. government.

Given their secretive nature, hiding in plain view on Beale Street across from the PG&E corporate headquarters in downtown San Francisco, there hasn’t been as much press about the company as there has been about publicly owned companies that are required to make regular reports and disclosures to a variety of regulatory agencies. A recent book by Sally Denton called The Profiteers: Bechtel and the Men Who Built the World, provides a remarkably revealing portrait of the long, sordid and ultimately catastrophic relationship between Bechtel and the U.S. government.

From the 1950s, Steve Bechtel, Sr. was already working hand-in-glove with the newly founded CIA.

As a charter member of the San Francisco-based National Committee for a Free Asia—a covert action organization determined to “roll back the dark forces of Soviet imperialism,” according to its 1951 originating prospectus—Steve Bechtel’s anti-Communist credentials matched those of McCone. The New York Times would later expose the committee as a front organization for the CIA, which was but one of many deep and long-standing affiliations between Steve and the intelligence community which he proudly embraced. He also served as the CIA’s liaison with the Business Council… (p. 75)

Enjoying high profits derived from the building of the Hoover Dam and subsequent government-financed construction projects, Bechtel funneled those profits into building a corporate empire that ironically depended on government financing while at the same time supporting politicians and militarists who rhetorically opposed government. Bechtel decided in the mid-1950s to embrace that ultimate government-sponsored pork barrel, nuclear power, as a way of further entering the energy market. Utilizing its well-developed technique of co-opting government officials, it hired away the Atomic Energy Commission’s nuclear reactor division head W. Kenneth Davis and his staff. “Davis thought his hiring ‘was a considered move.’ Davis ridiculed the naysayers of nuclear energy. He advocated building power plants as close as possible to consumers— such as on the outskirts of New York City—claiming that nuclear power ‘will not bring undue safety hazards to plant workers or public.’ “ (p. 71)

Working closely with Bechtel in the 1940s and 1950s was John McCone, a rabid anti-communist who became head of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and later took over leadership of the CIA after Allen Dulles fell out of favor with JFK subsequent to the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

Here are some select quotes about John McCone from Denton’s book:

McCone emerged an extreme anti-Communist during Truman administration. In 1950 he was appointed undersecretary of US Air Force (only 3 years old), where according to FBI report, “he favored his friends in the granting of contracts.” He was there at the founding of the CIA and the National Military Establishment in 1947, close to the Dulles brothers and other anti-Communist crusaders. (p. 66)

During the 1956 presidential election, John McCone, then a trustee of the California Institute of Technology and an avid sponsor of the H-bomb, had tried to get Caltech faculty scientists fired when they came out in support of a proposal to suspend the H-bomb testing… When questioned during his confirmation hearings[to head the Atomic Energy Commission] about his meddling with Caltech faculty, the stern, silver-haired McCone shared with congressmen his accusation that the professors were exaggerating the danger of radioactive fallout. “Your statement is obviously designed to create fear in the minds of the uninformed that radioactive fallout from the H-bomb tests endangers life,” he wrote to the scientists. “However, as you know, the National Academy of Sciences has issued a report this year completely discounting such danger.” (p. 70)

One of McCone’s projects while at the AEC was his attempt to provide Bechtel with small nuclear reactors that could be used for building tunnels and extracting oil. “McCone was positively rabid about the notion,” according to one account. “Think, he asked, of the things a Bechtel… could do with a few atomic bombs in its toolbox!” But Eisenhower quashed that scheme with a resoundingly simple, “No.” (p 72)

No one was more representative of the business and political culture of Bechtel in the modern era than John McCone. His grasp of the world oil economy and the cultivation of Arab states was singular. His vision of American exceptionalism, of corporate capitalism unfettered by regulations and interference, and of the symbiosis between government and private industry, would set the stage for Bechtel’s operations during the second half of the twentieth century. McCone would ascend from the AEC to the CIA, where he would oversee the expansion of that agency—a reshaping of the US intelligence complex that would result in yet more staged coups and global interventions. Bechtel would benefit immensely. (p. 74)

John McCone had disagreed adamantly with JFK’s interest in seeking conciliation with the Soviet Union, and, especially, with his decision to try to withdraw from Vietnam. He preferred LBJ’s Vietnam policy, and in a memorandum to the president, he recommended the deployment of more troops to “tighten the tourniquet” on North Vietnamese Communists. Bechtel would be one of the two top contractors to build the Vietnam War infrastructure; the other was Texas-based Brown and Root, which for decades had financed LBJ’s rise to power, and would later become Halliburton… A postwar audit by the Congressional Budget Office would reveal that Bechtel and Brown and Root “had billed the government for so much concrete that they could have put a concrete skin eight feet deep over the entire country of Vietnam.” (p. 82)

By the mid-1960s, the pattern was well set and Bechtel was a key part of the U.S. foreign policy and war-making apparatus. Already in the early 1950s Bechtel had seen the advantage of cultivating a revolving door between its own executive ranks and those in important parts of the U.S. government. An early example was Cornelius Stribling Snodgrass, a Bechtel board member “who participated in National Security Council (NSC) and CIA meetings where top secret covert operations such as the 1953 Iranian coup were planned, and then provided Bechtel with classified intelligence that would further its business interests.” (p. 76) This pattern would become much more obvious and extreme by the 1980s when George Schultz and Caspar Weinberger, both Bechtel executives in the 1970s, joined Ronald Reagan’s cabinet as Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense, respectively (curiously, Denton’s book reveals how competitive the two men were, and how poorly they got along with each other).

During his tenure at the head of the CIA, John McCone orchestrated events to benefit his corporate allies. In 1965 the CIA helped the Indonesian military overthrow President Sukarno, a nationalist leader of the 8th largest country in the world.

…(McCone’s) 1965 [CIA]-backed coup against Indonesia’s leftist president Sukarno. The longtime leader had become forcefully anti-imperialist, nationalizing US business interests and threatening Bechtel’s massive industrialization projects, which included an oil pipeline through the jungles of Sumatra. General Suharto replaced Sukarno and opened the country’s vast natural resources to Bechtel, which would become the state-owned oil company’s chief contractor not only for all oil projects but also for its liquefied natural gas operations. With Sukarno removed, Bechtel would receive millions in contracts to build one of the world’s most complicated telecommunications networks in Papua New Guinea, as well as to develop a gigantic copper mine on the Indonesian part of New Guinea. (p. 95)

Long before Reagan we had Richard (“I am not a crook!”) Nixon. After his narrow election in 1968 over Democrat Hubert Humphrey, the proverbial floodgates opened for Bechtel:

… the company became integrally tied with the president’s foreign policy and energy policy agendas… Nixon appointed both Steve Bechtel Sr., and Steve Jr. to plum government posts that enhanced the company’s financial portfolio. Steve Sr. assumed a position with the advisory committee of the US Export-Import Bank… while [he] was on the advisory board, Ex-Im loans to Bechtel included $13.5 million for nickel production, $107 million for a nuclear plant in Brazil, $100 million for a pipeline in Egypt, and $439 million for fertilizer plants and liquefied natural gas projects in Algeria. (p.95)

Nixon and his chief advisor Henry Kissinger orchestrated the overthrow of the government of Libya, installing the young Mu’ammar Qaddafi…. “[though] he shut down the British and American military bases… Bechtel [already in Libya for over a decade] would ramp up its construction of refineries and pipelines, and remain in Libya until Qaddafi’s capture and death in 2011.” (p. 96)

Nixon also engaged Bechtel in megadeals binding the country’s enemies in oil-rich lands to his envisioned world economy. Bechtel “moved quickly in the Middle East,” according to one account, “through huge construction projects to soak up the billions in American dollars that went to pay for the new OPEC prices of oil.” As part of this foreign policy and economic doctrine, Nixon also sought to improve US relations with the Soviet Union, as well as to find new markets for American exports—the two goals interwoven with multibillion-dollar loans from the Ex-Im Bank. The unlikely mastermind of Nixon’s grand plan to boost exports from $5 billion to $50 billion during his one and a half presidential terms was a California car salesman, GOP fundraiser, and erstwhile citrus grower named Henry Kearns. Nixon had rewarded his longtime political patron by appointing him president of Ex-Im Bank—a powerful position for an unqualified political party functionary with no lending experience. It had been Kearns who suggested Steve Sr.’s appointment to the bank’s advisory committee—with an eye toward bolstering Kearns’s and the bank’s credibility as they were embarking on a staggeringly large lending program. As much as any American businessman, Steve Sr. understood the intricacies and complexities of federally guaranteed loans, for they had built his, and his father’s, company. Under the close tutelage of Steve Sr., who would assume a central role in directing Kearns toward worldwide projects for Bechtel to build—projects that had been researched and selected by SRI—Kearns served as the company’s private banker, with seemingly unlimited access to funds. (p. 100)

Much of this seems like ancient history now in the early 21st century. But Bechtel’s role in Middle Eastern politics went well beyond building water and oil facilities for the Saudi monarchy or Qaddafi’s Libya. They worked hard to convince Saddam Hussein to pay them to build a major oil pipeline across Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war. Donald Rumsfeld, later George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense during the 2003 invasion, was sent as a private negotiator to Iraq in 1983 to lobby for the Bechtel pipeline (the photo of him shaking hands with Saddam Hussein would be reproduced countless times in years to follow).

Donald Rumsfeld shaking hands with Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in 1983, when Rumsfeld was sent to negotiate the building of a pipeline by the Bechtel corporation.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

Bechtel’s unmitigated decades-long wooing of Saddam Hussein would continue, including the relentless pursuit of the massive petrochemical plan to be built near Baghdad… When the US Senate passed a genocide bill invoking economic sanctions against Iraq for its use of chemical weapons—a bill that prohibited American firms from selling the restricted technology—Bechtel assured Saddam it would find a way around the prohibition…. a fact which elicited no comment from US Ambassador April Glaspie, who related details of the meeting in a classified cable from the embassy in Baghdad to the State Department in Washington. (p. 193)

Incredibly, given the long and loud demonization of Saddam Hussein by the same Republicans who worship Ronald Reagan to this day, it was the Reagan and Bush presidencies who, between 1985 and 1989 approved 771 licenses for exports of biological agents, high-tech equipment, and military items valued at $1.5 billion. A cynic might think they were building him up on purpose, in order to have an “enemy” who could be used to inspire fear and loathing later.

Finally, the long, dark history of Bechtel has been well hidden thanks to their aggressive strategy of attacking and trashing any critical coverage in the press, and freely bending the truth. In this regard, perhaps Bechtel can been seen as the trend-setting precursor to the Trump Era. They are an entity with decades of experience shaping public opinion through aggression, denial, and lying. Meanwhile they have been literally shaping the world through their aggressive expansion of fossil fuel and nuclear infrastructure, with the profits dependent on direct government backing and loan guarantees. The merger of corporate and state interests was forged ironically in the fight against fascism in WWII, and has only grown in strength since that time. Bechtel provides a model of the hypocrisy at the heart of the American system. “Like the Koch brothers and others in their political milieu, the Bechtel Foundation and its individual family members contribute to the Heritage Foundation, the antienvironmentalist Pacific Legal Foundation, American Enterprise Institute, Georgetown University Center for Strategic and International Studies, and other conservative thinktanks.” (p. 309) The worldview they’ve funded is the same one that claims it wants to shrink government to the size that it can be drowned in a bathtub. But without the state and its military adventures, its empire building, and its up-to-now bottomless pockets to fund all this mayhem, Bechtel would have had to make its way facing real competition—a pressure that may have led it to use its enormous resources in engineering, design, technology and basic science to create a world with a future, rather than the eco-cidal trainwreck on which we’re hurtling over the cliff today.