Armory

Historical Essay

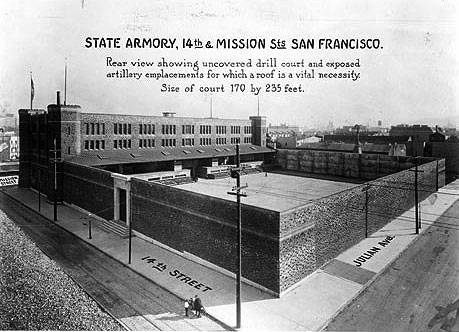

The armory at Mission and 14th Street, 1997.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The National Guard Armory was constructed in 1909 above an underground creek, to ensure besieged National Guardsmen would have drinking water. Its existence is testimony to the concerns of society's leaders in the early part of this century to maintain armored facilities to keep social peace at a time of widespread class war. The Guard vacated the building in 1976. After a long series of contested proposals for its contemporary use, including conversion to a movie studio, housing, or dot-com office space, the building was finally sold in 2007 to a pornography company, Kink.com, who uses it as a film studio.

The following is a more detailed history offered at the website of the folks who took control of the building:

The Mission Armory is located in the northern Mission District of San Francisco at the corner of 14th and Mission streets. It is the largest building of architectural importance in the Mission District. Similar to contemporary American armories, The Mission Armory represents a unique combination of revivalist architecture and early 20th century machine age construction. The Building is divided into two sections: the 84,700 square foot Administration Building and the 39,000 square foot Drill Court.

The Armory in 1928.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The exterior of the Mission Armory is designed to convey the impression of a heavily armored and forbidding Moorish fortress, with four octagonal towers, rough clinker brick exterior walls and narrow rectangular lancet windows. The building is constructed of a reinforced concrete frame consisting of twelve to twenty-one inch square columns. Concrete floor and roof beams span the length of the building to girders on the east-west grid lines. The exterior of the building features eight to twelve inch thick exterior load-bearing brick walls. In the Drill Court, the upper portions of the walls are thirteen inch thick unreinforced masonry.

The interior of the Mission Armory contains approximately 190,300 gross square feet of space and 160 rooms. While many of the more utilitarian spaces have simple, durable finishes, the reception stair lobbies, public/recreation rooms, and administration offices display high levels of design and finish materials, including marble, milled oak and walnut paneling. Although mostly concealed behind finish materials, the concrete frame is partially exposed in some areas, with beams and columns protruding into finished spaces.

The Basement originally housed a one hundred by sixty foot gymnasium, a natatorium (swimming pool), locker and dressing rooms, an industrial kitchen, a banquet room and the original quarters of the Naval Militia. The Basement, which extends beneath the Administration Building and the Drill Court, also contained an arsenal, company store room, boiler room, indoor rifle range, ammunition hoist, storerooms for field wagons and an elevator to haul the wagons to the vehicular entrances on Julian Avenue. However, the Basement is also the most heavily altered portion on the Mission Armory, many of the original brick and hollow clay and tile partition walls have been replaced over time with concrete masonry units. The most interesting features of the Basement are the exposed concrete frame and truss bases and Mission Creek, which runs beneath the building.

An earlier vision of the structure, probably in the mid-1910s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The Drill Court is one of the most significant interior spaces in the Mission Armory. It is reputed to be the largest unsupported enclosed volume in San Francisco, featuring a dramatic exposed roof structure composed of curved steel open-web trusses. A reinforced-concrete balcony accessible from the third floor of the Administration Building runs around the perimeter of the Drill Court, sixteen feet above the floor. This was added in 1925 to provide a base for bleachers for boxing matches. The 170-foot-long roof trusses support the entire width of the barrel vaulted wood roof without intermediary vertical supports. The San Francisco National Guard Armory and Arsenal, as it is listed, was nominated to the National Register in 1978 for three areas of significance: architecture, engineering and military; for the period of significance 1900-1912. As an exceptional example of the work of the architectural firm of Woollett & Woollett (led by State Architect John F. Woollett), the building originally housed the California National Coast Guard Artillery, the naval Militia, and later acted as a social center for the City’s national guardsmen.

Between 1870 and 1906, Italianate and Eastlake style flats, built by firms such as The Real Estate Associates (TREA), and cottages erected by individual homesteaders went up on newly subdivided parcels of the Mission. The socio-economic level of the Mission neighborhood was generally middle-class although not as affluent as other Victorian streetcar suburbs such as the Western Addition. The 1906 Earthquake and Fire was a watershed event in the history of the neighborhood, however. This event transformed the district from a quasi-rural streetcar suburb into an industrial district populated principally by working class Irish and German immigrants.

In the years following the 1906 Earthquake, the San Francisco based units of the National Guard were quartered in a temporary wood frame structure on the southeastern corner of Van Ness Avenue and California Street. Two-and-a-half years later, in January 1909, Captain Herman G. Stundt, began actively lobbying Governor James Norris Gillett for funds to construct a new modern armory that would consolidate the dispersed local companies into one facility. On April 20, 1909, Governor Gillett signed a bill appropriating $420,000 for the construction of a new armory, with the caveat that the citizens of San Francisco raise $100,000 to purchase the land. As a first step in the process, Governor Gillett consolidated all four companies of the local Fifth Infantry into the 250th Coast Artillery. In spite of repeated fundraising pleas from the editor on the San Francisco Call newspaper, San Franciscans raised only $60,000 by the end of 1909. Reiterating the editorials in the Call, the director of the San Francisco Real Estate Board appealed to the patriotic sensibilities of San Franciscans. When this tactic failed, he pointed out the large number of lucrative construction contracts and local equipment and supply purchases that would result from the construction of the armory. The funds were raised.

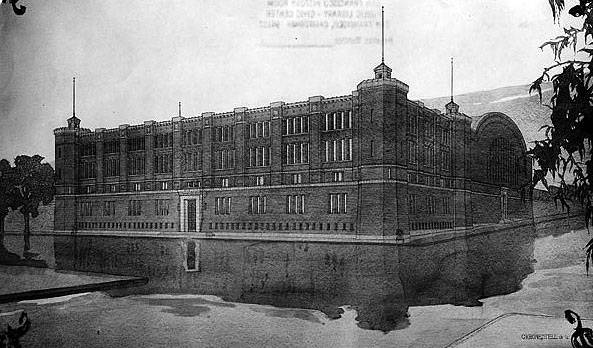

Armory in artist's rendering, 1912.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Wollett’s designs were finalized and the contract put out to bid in August 1912. The contract was awarded to the construction firm of McLeran & Peterson. Construction began in September 1912 and proceeded steadily for a year and a half. By June 1914, the new California Armory and Arsenal was completed and occupied. Departing from many contemporary armories in cities of the Northeast and Midwest, the Mission Armory was designed within the context of California’s architectural traditions. Interchangeably labeled by Wollett as being either a Spanish or Moorish fortress, the Mission Armory made use of features and materials typical of California’s contemporary regional Mission Revival and Arts and Crafts movements, clearly departing from the Gothic or Romanesque styles popular back East. The final cost of the building was approximately a half-million dollars, including the land. When completed (minus the Drill Court) an article in the San Francisco Chronicle claimed: “San Francisco now has one of the finest armories in the United States, not only in point of cost and equipment, but in point design.”

The new California Armory and Arsenal would house then companies of the Coastal Artillery, two divisions of the Naval Militia, one Signal Corps one Engineering Corps and several other divisions of the California National Guard brought in from Oakland and San Mateo. Almost as important as its military purpose was its promised role as a social and recreation center for Guardsmen. It was believed that the multitude of amenities and activities offered would help to recruit men into the service of the California National Guard. From its completion in 1914 onward, the Mission Armory served as a social center for National Guardsmen, many of whom were recruited from San Francisco.

From 1920s through the 1940s, the Mission Armory served as San Francisco’s primary sports venue, eventually earning the nickname the Madison Square Garden of the West. For almost three decades, at least two prizefights were held in the Drill Court each week, usually on Tuesday and Friday nights. One very notable fight included a light heavyweight title fight between Young Jim Corbett III and Jackie Fields. Other notable fights that took place in the Mission Armory included matches between Mike Teague and Armand Emanuel (Teague was the World Light Heavy Weight Champion); Jackie Fields and Jack Thompson (both were welterweight champions); and Young Jim Corbett and Pete Myers in 1929.

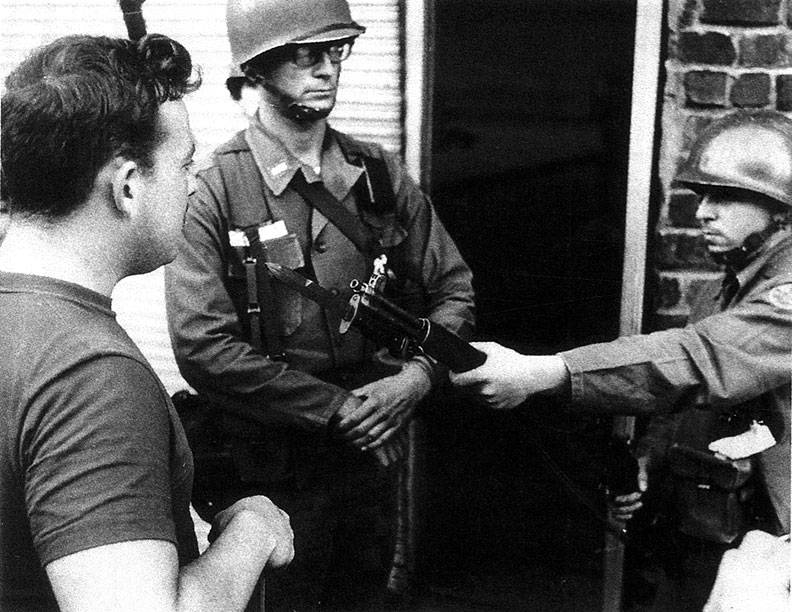

After the Korean War, the Mission Armory slowly lost its value as a military training facility. By the 1950’s, close-order drilling was no longer a central part of the National Guard’s training regimen. World War II era technological advances in air warfare rendered coastal batteries outdated. With the 250th Coast Artillery converted into an anti-aircraft unit, there was no longer any need for the large non-firing field guns installed in the Drill Court; they were removed in 1947. After the Korean War, training at the Mission Armory became centered on classroom instruction. With a large and permanent standing Armory, the California National Guard was increasingly deployed to the sites of natural disasters and to quell riots, including the Riots of 1966 in San Francisco’s Bayview–Hunters Point district. By the late 1960s, the Mission Armory was deemed obsolete, and in 1973, the California National Guard announced its intention to move operations to a new armory at Fort Funston.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/Clip12ArmoryRiot" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Infamous revolutionary and journalist John Ross describes his experience with the Mission Rebels and the Progressive Labor Party in 1966 blockading the Armory in solidarity with the uprising in Hunter's Point.

Video by Chris Carlsson

Progressive Labor Party member Jay Frank confronts National Guard at Armory door, September 1966.

Photo: El Puente de Claudio

After the California National Guard vacated the Mission Armory, the building was used sporadically over the next few years by various entries. The San Francisco Police Department established an after-school boxing program for neighborhood youth but few other agencies or organizations stepped forward to claim the building for any full-time use. In 1976, George Lucas used the Drill Court to film some scenes for Star Wars but plans to convert the building into a full-time film studio never came to fruition. In 1974, a citizens group called the Mission Planning Council (MPC) set up the Mission Armory Task Force to develop a plan for the building’s reuse. The first step involved convincing the State Services Administration to declare the building surplus property and to sell it to the City. As city property, the MPC hoped to find a developer to reuse the building. They envisioned a weekly Mercado, combined with dances, concerts and sporting events, taking place in the Drill Court. The MPC hoped that this commercial component would pay for the renovation of the Administration Building on Mission Street. Additional intended use included neighborhood non-profit office space, a recreation center, a theater and a branch of City College.

The neighborhood reuse efforts came to a standstill in 1975 when the California National Guard was evicted from its new quarters at Fort Funston to make way for a new sewage treatment plant. Faced with the prospect of returning to the Mission Armory, the California National guard developed plans to demolish the building and replace it with a modern facility with ample surface parking. Mission residents, determined to prevent the building’s demolition, actively pursued landmark status for the Mission Armory. In 1978, the Mission Armory was listed in the National Register, and a year later it was designated San Francisco City Landmark #108. In 1979, the California National Guard abandoned their plans to replace the Mission Armory and decommissioned the building.

In 1980, the Mission Armory was declared surplus property by the State Services Administration and put up for sale. The Drill Court was still used occasionally by the San Francisco police Department (SFPD) for boxing matches and by the San Francisco Opera for building sets. In that same year, a team of consultants including Charles Hall Page & Associates, Sanger & Associates and others developed a reuse plan for the building. As the largest public assembly space in the City, the options seemed endless. However, the cost of rehabilitating the structure and bringing it into conformance with modern seismic and life-safety codes were too formidable for any developer. Throughout the 1980s, a series of development proposals emerged. In 1986, a private developer purchased the Mission Armory and planned to convert the building into market rate housing but abandoned his plans in the face of neighborhood opposition. Later that same year, another developer made plans to convert the Armory into a movie studio but this proposal also failed to materialize. In 1996, a taskforce, lead by City Supervisor Susan Leal recommended that the City purchase the Mission Armory, but by this point the State was already in negotiations with a private developer. In 2000, yet another proposal surfaced to convert the building into dot-com office space. When this effort collapsed in the face of intense neighborhood opposition, plans were amended to convert the Mission Armory into a server farm for computer equipment. This plan also failed to gain support, and the building remained empty until January 2007 when Armory Studios, LLC purchased the building.

from SF Armory