1960’s Folk Music at the hungry i and SF Folk Music Club

Historical Essay

by Claire Huang, 2019

| San Francisco became a hub for folk music in the 1960s with the help of two institutions: Enrico Banducci’s the hungry i nightclub, and Faith Petric’s San Francisco Folk Music Club. Banducci debuted and fostered influential performers like the Kingston Trio, while Petric created a long-lasting group of San Francisco folkniks who embraced activism and community. |

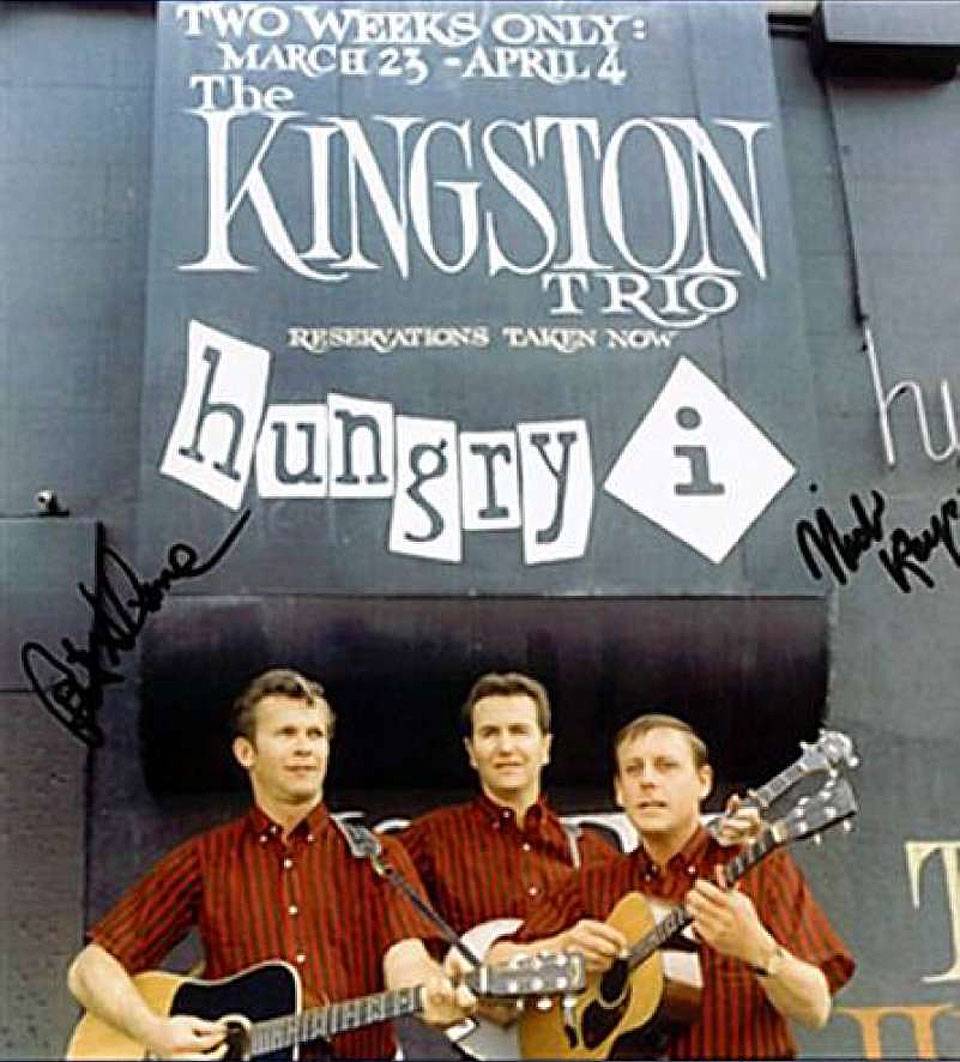

Kingston Trio at the Hungry i, early 1950s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, AAB-1223

During the 1950s, American folk music was forced underground by the Red Scare. Folk musicians, whose left-wing political leanings were often interpreted as Communist sympathies, were added to the industry blacklist called “Red Channels” (Driver). Musicians who escaped the jaws of McCarthyism concentrated in pockets of bohemian safe havens around the country. Alongside New York City’s Greenwich Village and Chicago, San Francisco claimed a spot as one such gathering ground. With the help of two people—Enrico Banducci of the hungry i nightclub and Faith Craig Petric of the San Francisco Folk Music Club—San Francisco’s folk music scene rose to national prominence, leading the 1960’s folk revival and shaping the genre for decades afterwards.

Pre-1950s, folk music culture was already present in the United States. It was often associated with social solidarity in leftist contexts, the most prominent of which was the Industrial Workers of the World’s “little red book” of protest songs (Eyerman and Barretta). This focus on social solidarity shifted from giving labor movements a voice to combating the modernization and homogenization of postwar America (Moore). This shift coincided with the emergence of the Beat Generation counterculture, which in part sought to form a nonconforming, collaborative community of creative artists (Moore). San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood’s hub of Beat poets and vibrant nightlife scene set it up to be a “fertile, overlapping ground for both Beat culture and folk music enthusiasts” (Cohen 121).

At the center of the North Beach action was Enrico Banducci and his nightclub, the hungry i. Banducci took ownership of the nightclub in 1951, and for twenty years, he ran it as impresario, hand picking comedians, jazz musicians, and folk musicians (“the hungry i”). The hungry i served as the launchpad for many famous performers: comics Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, singer Barbra Streisand, and satirist Tom Lehrer (“the hungry i”), among others. In addition, the nightclub’s red brick wall stage backdrop was the first of its kind and has since become a trademark of comedy clubs. The hungry i’s reputation wasn’t just limited to the Bay Area: New York Times music critic Howard Taubman called it “the most influential night club west of the Mississippi” (Taubman).

courtesy Museum of Performance and Design

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/8s6v2n8UG0E" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

trailer for Hungry i Reunion documentary

Despite the nightclub’s growing fame, Banducci was careful to maintain a very particular creative environment in the hungry i. He frowned upon the one-dimensional, entertainment focus of other nightclubs and thought of the hungry i as a theater: “I wanted a place where a lot of expression went on” (Banducci). When performers didn’t meet his standards, Banducci wasn’t afraid to cut them off with a blackout and end-of-show announcement (Nachman).

But of the performers he did keep, he held them in high esteem. Himself a gifted concert-violinist respectful of the world of artistry, Banducci expected the same respect from the audience. He banned hecklers and was known to fistfight with those who didn’t comply (Nachman). A regular audience member summed up his policy: “At the I, you either listened or left. No in between” (“the hungry i”). Banducci’s protectiveness of his performers was well-received; in the words of comedian Shelley Berman, “Enrico really cared for the talent and watched out for them” (“the hungry i”).

Enrico Banducci on scooter, c. 1960.

Photo: Suki Hill

Banducci’s focus on the performer and artistic expression, combined with the North Beach location, made the hungry i fertile ground for folk music cultivation. Indeed, one of the hungry i’s headline acts, the Kingston Trio, catapulted folk music into national prominence. Formed in 1957, the trio was a group of fresh Bay Area college graduates who began performing in Palo Alto coffee shops, then San Francisco’s tiny Purple Onion nightclub (known as the “training ground...for young performers” (Bareiss)). The trio finally moved to the hungry i, which was where they “developed its signature sound and early repertoire” in the creative ambience that Banducci fostered (Bareiss).

A year later, the trio released their first album, filled with songs learned from other San Francisco performers they encountered at various nightclubs (Bareiss). Their rendition of “Tom Dooley”, an old folk song about a love triangle that ends in murder, instantly topped the charts, selling three million copies and winning a Grammy as the first big hit of the folk music revival (Cohen 131). Their second album was recorded live at the hungry i. The trio’s success proved the commercial popularity of folk music and paved the way for folk newcomers like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Phil Ochs (Dreier).

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/RRyNmRq6ULQ" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

“Tom Dooley”, Kingston Trio live at the Hungry i, 1964

However, the Kingston Trio was not well-received by all. Given the McCarthy era political climate, the trio intentionally steered clear of radical topics, breaking from the folk tradition of decades past and the North Beach Beat culture that had initially shaped them. Folk music magazine columnist Ron Radosh criticized the trio for bringing “good folk music to the level of the worst of Tin Pan Alley [popular] music, and...even worse...advertising itself as folk music” (Cohen 136). In the struggle between folk authenticity and commercial popularity, the Kingston Trio chose to sacrifice the former for the latter.

San Francisco Folk Music Club

Meanwhile, on the other side of town in Haight-Ashbury, Faith Petric was cultivating San Francisco folk music on a more local stage. Starting in 1962, Petric led the San Francisco Folk Music Club, a group of musicians and music lovers born out of the Cold War era and founded on the belief that “music is the one language capable of transcending national egotism” ("Who we are"). Under Petric’s leadership, the Folk Music Club transformed from a scrappy gathering of high schoolers into a consistent community ("Who we are").

San Francisco Folk Music Club at Faith Petric's, 855 Clayton, in the upper Haight, c. 1974.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, AAB-8842

One hallmark of the club was Friday night “Song Swap and Jam” sessions, hosted in Petric’s home. Despite lack of advertising, the sessions would regularly draw as many as 100 San Franciscans in its heyday (Marech). In Petric’s words, "There'd be so many people in the living room, you couldn't sit down" (Marech). Folk Club members like Richard Rice described the gathering as an “extended family,...like people hanging out, playing on their porches. You don't find that much anymore” (Marech). Through the Friday night jam sessions, Petric fostered an intimate folk music atmosphere similar to Enrico Banducci’s hungry i, if not even more tight-knit, collaborative, and long-lasting. Despite Petric’s passing in 2013, the jam sessions continue to this day.

San Francisco Folk Music Club at Faith Petric's, 855 Clayton, in the upper Haight, c. 1974.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, AAB-8858

While Banducci focused on cultivating a set of impressive, mass-marketable folk music performers like the Kingston Trio, Petric embraced a more grassroots folk music ethos. To her, folk music “tells the truth about history—not just lessons from school about generals and robber barons and politicians. It's about the lives people lived and what happened to them. The tragedies, hopes, dreams—all of that. Folk music is what folks sing" (Vaziri). Petric led by example, bringing her music to her own activism; unlike the Kingston Trio, she did not shy away from political topics. She sang in protests at Selma and against the Vietnam War (Marech), and also co-founded the Freedom Song Network, a group of Bay Area musicians who lend their voices to social activism events (Scherr).

Faith Petric jamming at age 86.

Photo: Gina Gayle, SF Chronicle

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/P7mXynh9HG0" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Faith Petric's 95th Birthday Benefit at the Freight and Salvage, Berkeley, CA, September 2010. "She Was There," written by Estelle Freedman (vocal). Marisa Malvino (vocal), Peter Kessler (guitar), and Don Burnham (bass).

Both Enrico Banducci and Faith Petric fostered their own creative, welcoming San Francisco folk music environments. Banducci focused on identifying and nurturing performers who were at the peak of their art forms and were capable of pushing or even redefining the national boundaries of music during their brief moment in the spotlight. Petric used her own deep passion for folk culture to foster a local, longer-term community of musicians who focused on embodying folk collaboration and activism. Combined, they cemented San Francisco’s local and national influence on folk music.

Bibliography

Bareiss, Warren. “Middlebrow Knowingness in 1950s San Francisco: The Kingston Trio, Beat Counterculture, and the Production of ‘Authenticity.’” Popular Music and Society, vol. 33, no. 1, 2010, pp. 9–33., doi:10.1080/09672550802340671.

Cohen, Ronald D. Rainbow Quest: the Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940-1970. University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Dreier, Peter. “The Kingston Trio and the Red Scare.” HuffPost, HuffPost, 25 May 2011, www.huffpost.com/entry/the-kingston-trio-and-the_b_134683.

Driver, Richard. “The Kingston Trio.” The Grove Dictionary of American Music, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2013.

Eyerman, Ron, and Scott Barretta. “From the 30s to the 60s: The Folk Music Revival in the United States.” Theory and Society, vol. 25, no. 4, 1996, pp. 501–543., doi:10.1007/bf00160675.

Marech, Rona. “PROFILE / Faith Petric.” San Francisco Chronicle, 30 Sept. 2002, www.sfgate.com/news/article/PROFILE-Faith-Petric-It-s-all-about-the-song-2790723.php#item-85307-tbla-2.

Moore, Ryan. “‘Break on Through’: Counterculture, Music and Modernity in the 1960s.” Volume!, no. 9 : 1, 2012, pp. 34–49., doi:10.4000/volume.3501.

Nachman, Gerald. Seriously Funny: the Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s. Back Stage Books, 2004.

Scherr, Judith. “Freedom Song Network Turns 25.” Berkeley Daily Planet, 12 Oct. 2007, www.berkeleydailyplanet.com/issue/2007-10-12/article/28206.

Taubman, Howard. “Mort Sahl Returns to the Hungry i in San Francisco.” New York Times, 12 May 1961.

“The Hungry i.” Enrico Banducci's Legendary Hungry i, www.hungryi.net/.

Vaziri, Aidin. “S.F. Folk Music Club Leader Faith Petric Dies.” San Francisco Chronicle, 11 Nov. 2013, www.sfgate.com/music/article/S-F-Folk-Music-Club-leader-Faith-Petric-dies-4975619.php.

“Who We Are.” SFFMC, www.sffmc.org/whoweare_body.html.