Rainbow Grocery Stories From the Early Days

"I was there..."

by Ryan Sarnataro, 2025

This is basically a day's to do list, from October 10, 1978. Typed below is a bit of translation. It is a snapshot of what my Rainbow life was like. Now I wasn't the typical Rainbow worker as I had my hands in not only the basic stuff like 2 hours of cashiering and stocking shelves but buying, organizational development and interface with federal regulatory agencies.

Courtesy Ryan Sarnataro

Rainbow was started as an outgrowth of an ashram buying club. The guru was vegetarian and therefore so was Rainbow, which, amazingly, has continued to this very day.

Rainbow workers tended to be either (or both!) followers of Guru Mahara Ji and/or idealistic young people who had chosen not to pursue the middle-class American Dream. A main impetus for the store were the current ideals of democratic governance being fair, natural, able to provide genuine services, which "capitalism" could not, and that we the people could do better for ourselves. Another strong motivation was a desire to fulfill the need for natural and organic food, which was not widely available.

To become a worker at Rainbow you’d strike up a friendship with someone and start volunteering. After a month or so you might be offered a paid shift. There was no concept of being an owner, you being a member of the collective gave you a type of ownership—a voice in a democratic workplace. There were regular meetings where policies and issues were worked out and each person attending had a vote. Rainbow did not operate by consensus, which was popular at the time. If you showed up, which you did on your own time as meetings were unpaid, you had a voice though unlike consensus you did not have a veto.

Originally Rainbow was incorporated as a for profit company with nonprofit oriented bylaws. The people who signed the original documents, all disciples of the guru, were known as “the incorporators”. There was tension over the possibility of Rainbow becoming property of Divine Light Mission—which was the original intent—but things quickly moved past that. Instead, we started a process to reform our governance documents with the help of Briarpatch network volunteers which included Michael Phillips (who wrote The 7 Laws of Money—one of the first books demystifying the subject), Roger Pritchard, Claude Whitmyer, and the high powered downtown lawyer Sterling Johnson. Eventually the incorporators, people who on paper were the owners of a thriving business, gave their ownership to the collective which later became the co-op for no financial gain.

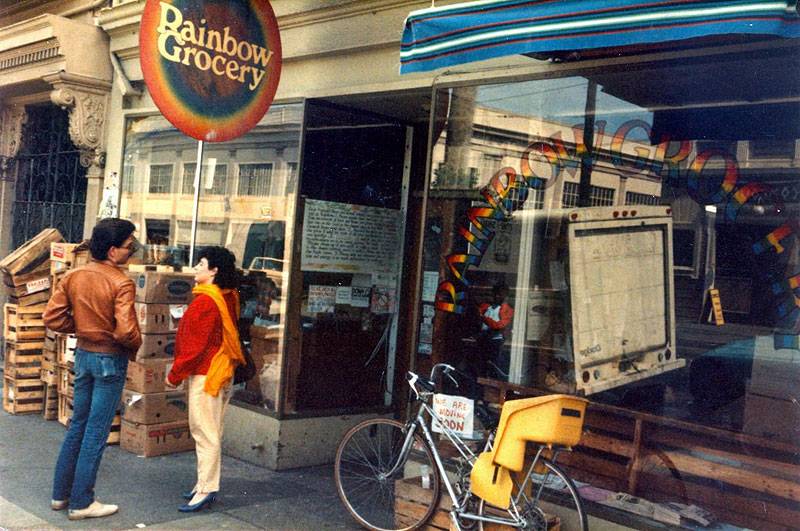

Rainbow Grocery at 3149 16th Street in the 1970s.

Photo: courtesy Judy Davis

Rainbow stood apart from much of the People’s Food System due to our non-political orientation. We were more spiritual and service oriented, meditating in the front of the store located at 3159 16th Street each morning. This lack of revolutionary zeal did not go unnoticed and we gained the moniker “a bunch of hippies playing store”. Fortunately some of those hippies had years of business experience and a prodigious work ethic. Rainbow was also helped with business guidance from the Mission Economic Development Association and some experienced community volunteers.

Early Rainbow Grocery worker, Rik Penn, at a Shaping San Francisco hosted walking tour in front of the first Rainbow storefront, August 2025. Among having other roles, Rik worked on building out the space through its growth.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Despite or maybe because of our non-political orientation we were the most diverse collective. Even when there were only a couple of dozen of us, we had black, gay, Chinese, and—of course being in the Mission District—Latino workers. Gosh we eventually had a trans member, almost unheard of in those days. What we didn’t have was anybody over about 40 years old. We weren’t exactly the movie Wild In the Streets (tagline: don’t trust anyone over 30) but the alternative-to-capitalism world back in those days was almost entirely idealistic young people.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of workers, wedded to the mission, were honest, like most of the collectives in the People’s Food System, Rainbow suffered from insider theft. Fortunately, our embezzler was a very responsible bookkeeper who was stealing both for himself and his guru. Realizing the store was approaching insolvency he knew there was just one solution. He went to a meeting and got everyone to vote for a pay cut due to “slow summer sales”.

Cofounder Bill Crolius explains how the store received deliveries during a Shaping San Francisco hosted walking tour in August 2025.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

The original 1700 sq. ft. storefront had no back door so all deliveries came in the front door, mostly during business hours. Originally the compressor running the walk-in refrigerator was on the floor blowing hot air on all the back-stock of bulk food. One of the Food System’s assets was People’s Refrigeration, two crack HVAC guys who moved the compressor to the top of the refrigerator so it could vent into the store. That was better for the food but pretty noisy, though eventually a worker installed insulation to muffle the sound.

Wages started at $10 per shift, a shift being 4 1/2 to 7 hours (the longest was produce on days when the store was open late because you couldn’t start to put things away until the store closed and you had to place the next day’s order). When we finally went to hourly our pay was $3.25 an hour while the federal minimum wage was $2.65. Same rate for everybody. By the end of the 1970s we were making twice the minimum wage in a time of 13% inflation.

Rainbow was way ahead of things when it came to technology. We were one of the first food stores—including for profit ones—to install electronic cash registers with an integrated scale. The collective voted to buy them despite the manufacturer also having connections with the defense industry, something debated at a meeting. One high tech feature of the new cash registers was the ability to print programmable text at the top of the receipts. The collective voted for them to say “Rainbow Grocery - Love and Food”.

In 1977 there was a showdown in the People’s Food System between people sincerely motivated by the slogan “food for people, not for profit” and an ex-prisoner’s gang called Tribal Thumb who tried to take the political high ground due to their “oppression” but were really using the food system as a cover for criminal activity. At a Food System meeting they brought out their guns and one person was killed and others wounded.

The Veritable Vegetable staff in 2023.

Image: Veritable Vegetable

The Veritable Vegetables (VV) collective ejected their gang infiltrators but nonetheless were targeted to be put out of business through a boycott led by the Common Operating Warehouse. Rainbow voted in a meeting to refuse to join the boycott and at one point was 40% of VV’s volume. VV survives to this day while the businesses on the other side of the conflict are long gone.

VV was a mix of men and women back in those days, then they decided to become a lesbian collective. This meant the men working there needed to find another job. Rainbow was fortunate enough to hire a very experienced produce buyer who then began do most of the produce shifts. He got Rainbow involved in advocacy for the groundbreaking organic legislation which established labeling requirements and an office to investigate fraudulent claims. The legislation required labeling, “Grown and processed in accordance with the California Organic Foods Act of 1979” which spread throughout the nation because California was such a large market.

A couple of years after the store got started the guru decided his followers should no longer eat “impure” eggs. So they came to a meeting and wanted the store to stop selling them. They were outvoted. This was the first time the non-guru members took control of things.

With the advent of the electronic cash registers and a special computer program written to tabulate sales it became apparent to our bookkeeper the embezzlement was going to be found out-so he decided to confess in a meeting after coming clean to the treasurer. The collective voted to forgive (aka not prosecute) him and soon our pay was restored. He very quickly left town. The trusted and well-loved neighborhood cleaner who let in a group of guys who stole tons of food at night was also not prosecuted. We caught her with a sting operation. She was immediately fired. The betrayal stunned many workers in the collective.

The Grocery Store did not have the room for all the products our customers wanted, so the General Store was born in a separate location down the block, at 3169 16th Street. It was supposed to make a good amount of money, after all it sold higher priced items with a bigger profit margin. Instead it was bleeding cash and putting a strain on the grocery store. The solution was to do an inventory, which involved counting everything in the store on the evening of November 6. Cashiers after that paid close attention to hitting the right buttons for each department. When all the calculations were done following the New Year’s inventory it was discovered the Vitamin department was losing money. Inquiry revealed the buyer had been giving a 10% discount off of cost instead off of 10% off of suggested retail. Properly educated she kept her job as vitamin buyer. The General Store never lost money after that.

The General Store bought some display cases and positioned a register at the front door, which no doubt cut down on shoplifting. Still people tried and sometimes workers would run down the street and get merchandise back from the thieves.

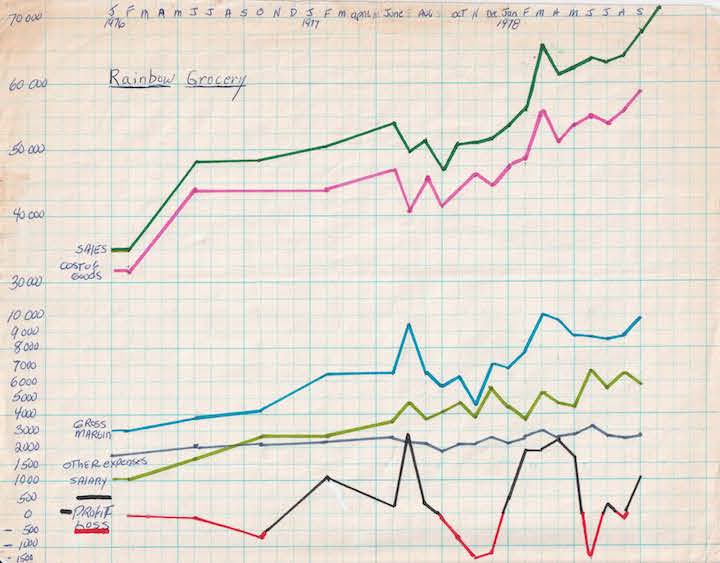

A chart of the financial statements I made. It shows how explosive the growth was in the first years.

Courtesy Ryan Sarnataro

The General Store was quite a success story doing a huge business not only in vitamins and “bath & body” but in housewares, successfully competing with the likes of Macy’s Cellar and selling thousands of new-fangled swing arm lamps. We also had gift items and during the exciting Christmas rush would need two people on each of the two registers to handle the volume.

Rainbow Grocery grew, in part, by squeezing more product into our tiny 1700 sq. ft. space. This meant building shelves where there had been empty space, changing from selling bulk out of barrels to efficiently designed bins with shelves on top. Sure enough more stuff to sell meant more people buying and the quiet zone with potted plants in the front window was supplanted by a third cash register. The store went from Sunday as a day of rest to being open 7 days a week when five workers volunteered to work that day, initially keeping the store open for just 5 hours.

Profit margins are vital even if food is for people. One way they were increased over the 10%/20% markup policy was by pocketing rather than passing on sale prices and bulk discounts being offered to us by sales reps. Our highest-in-the-food-system volume meant access to special deals. We began to forward buy, stocking up on sale items and doling them out over the next month or so. Still our pricing policy was egalitarian. We wanted the little old lady buying 25¢ worth of masa harina to pay the same unit price as someone loading up a shopping cart. Rewards programs and volume discounts were considered just another way to subsidize the well off and discriminate against the poor.

The walk in cooler was a very busy place with different department stockers taking care of their inventory. Workers were free to make their own rules and so some were in there barefoot. I was in there once bumping against another worker when she said to me–“Did you hear, I’m in labor”. Obviously, the shelves needed to be full before she went off to give birth. This was the kind of work ethic that made Rainbow successful.