Reflections from Occupied Ohlone Territory

Historical Essay

by Mary Jean Robertson

Listen to an excerpt from "Reflections from Occupied Ohlone Territory" read by author Mary Jean Robertson:

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/4TenYears--fromOccupiedOhloneTerritory" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

by mp3.

![]()

Previous stop: Labor sights and smells

Next Stop #5: Underground comix

Sacred sites were being destroyed. Nations were terminated. Drug and alcohol addiction was rampant on the reservations. Something had to change. The people told a story, had a vision, sang a ghost dance song. The young people gathered on the western edge of Turtle Island and the smoke of the tobacco, cedar, and sage carried their prayers to the creator. The spirit of the people would start in the West and return to the East to bring a new consciousness of sovereignty and self-determination to the Native Nations.

All over the world Nations were gaining independence from their colonizers. Young men were fighting, dying, and returning from Vietnam. Women were changing roles and status. In the city that birthed the United Nations, an invisible minority took a step into the spotlight of history.

“Alcatraz, Alcatraz, none has seen your beauty like the Indian has.”

—Redbone(1)

A sign on the Alcatraz landing welcomes arriving Indian people.

From the great gallery of Alcatraz occupation images at Indigenous People of Africa and America online magazine.

Indian people sit in the back of a boat leaving for Alcatraz Island. LaNada Boyer, left, talks with Joe Bill, center, and an unidentified man.

The two decades leading to the occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 were the most difficult for individuals to deal with. Life for Indian peoples was like a pressure cooker. Generations of children were taken from their families to suffer in government- and church-sponsored boarding schools.(2) The families lost their traditional ways of passing information through stories and example. The religions and languages were attenuated to the point of disappearance. The children of the boarding schools were suffering from the first forms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Stockholm syndrome. They were encouraged to identify with their captors and learned the lessons of punishment. Traditionally in Native societies children were cherished, corporal punishment was unheard of, and the cutting of hair was a sign of mourning the death of a close family member. The bewildered children brought to the schools thought that they had lost their family forever when the staff cut their hair to make them conform to the White culture’s sense of civilization.

World War II brought the warriors to the forefront where the traditions of defending the lands of the people translated into serving in all branches of the Armed Forces.(3) After the war the knowledge of how people were treated outside of the reservation led to anger, depression, and despair. It was at this point that the Government, wanting to solve the “Indian Problem,” came up with a three-pronged approach. The tribal government-to-government status promised by treaties would be terminated (a unilateral abolition of Indian sovereignty). The American Indian Civil Rights Act promised individual Indians the right to the same rights and responsibilities of any other citizen without any of the group rights guaranteed by the treaties. The federal Indian Relocation Act of 1956 promised jobs and housing assistance if families would move off the reservations into the cities.(4) San Francisco was a terminus point for the relocation program on the West Coast. The plan was to terminate the Government’s treaty responsibilities to the Indian Nations because all their citizens would have become assimilated Americans. There was a policy in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Indian Health Service (IHS) to consider all Native Americans who had left their reservations as non-Indians and therefore not eligible for housing, healthcare, or any other federal programs for Native Americans. The next generation of children was supposed to lose their identity as tribal members and become ordinary working-class Americans, just like all the other ethnic minorities were melting into the dominant culture.

The social workers, the Mormon Church, and the IHS worked together to remove Indian children from their families so that they could be adopted into White families where they would not have to suffer the poverty and hunger that existed on the reservations. The Indian Health Service practiced their own form of eugenics, sterilizing most young women who gave birth in the IHS hospitals.(5)

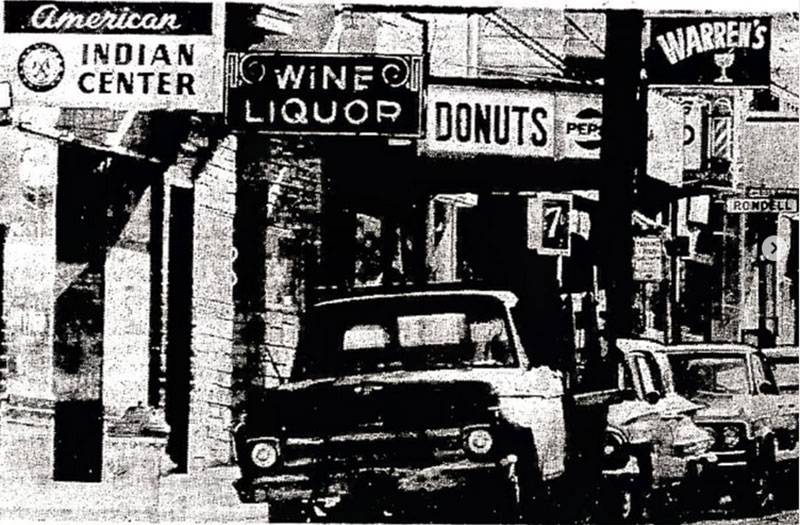

In Vietnam, American Indians once again served in the US armed forces in a much higher per capita rate than any other group. The young men, trained to fight for democracy, freedom, and justice came home and found their homelands invaded, their people in poverty and despair. They used the GI bill to go to school to learn how to bring back hope to their people. John Trudell had served in the Navy, Richard Oakes was using the GI bill to attend San Francisco State College. The San Francisco American Indian Center burned to the ground in October 1969 and there was no longer a meeting, gathering place for all the displaced Indians. No place to have memorial services, no place to have potluck dinners, no place to get a little help with the social service agencies, a job search, the cops. No one to help with a little money to get back home or to translate English so that an ID for work was obtainable.

Original American Indian Center at 3053 16th Street before it burned in October, 1969.

Photo: San Francisco Chronicle

The American Indian Movement was patrolling the streets of Minneapolis to protect Indian people from the police. San Francisco State College was on strike. Students and teachers were meeting outside the classrooms and demanding relevant courses. The demands of the Civil Rights Movement resonated with the Indian peoples. The Reies Lopez Tijerina Courthouse raid in New Mexico (6) demanded a more activist approach to challenge government policies. It was into this perfect storm of possibilities that the determination to occupy Alcatraz Island was born. The San Francisco movers and shakers came up with a plan to exploit Alcatraz Island to make money for the wealthy elites. Mr. Lamar Hunt of a Texas oil money family tried to buy Alcatraz Island for $2 million and turn it into a $4 million tourist park, landscaped with a shopping area that resembled San Francisco in the 1890s. That was the last straw.

Just as when a pot of water is put on the stove to boil, and a few air bubbles form on the bottom and crawl up the sides of the pot, the Alcatraz Occupation had a few early attempts. In 1964 a group of young people landed on the Island and claimed it by right of the Sioux treaty of 1868. This claim was taken to Federal Court. Judges are very conservative, they could have determined that the Ohlone people were the original inhabitants of San Francisco and returned the land to them. Instead the court determined that the treaty only applied to the Sioux and other signatories of that treaty and did not apply to the West Coast at all. Again on November 9, 1969, Adam Fortunate Eagle, Richard Oakes, and others took a symbolic cruise around the Island on the Monte Cristo. Halfway around the Island Richard took off his shirt and dove into the water to swim to Alcatraz; he was followed by several others. Joe Bill, an Alaska Native familiar with the sea jumped when the boat was a little further along so that the tide would carry him to the Island. His was the only successful landing of that cruise. Later that night 14 activists spent the night on the island only to be returned to the mainland by the Coast Guard on the following morning. The 18-month occupation really started on November 20, 1969, at about 2:00 a.m., when almost eighty American Indians from more than 20 tribes landed on Alcatraz. Some stayed for the full 18 months of the occupation, some only for a day or two, but in the end over 5,600 Indians of All Tribes claimed “the Rock.”

Alcatraz changed everything. The event resulted in major benefits for American Indians. In his memoirs, Brad Patterson, a top aide to President Richard Nixon, cited at least ten major policy and law shifts. (Bradley H. Patterson, Jr. The White House Staff: Inside the West Wing and Beyond (Brookings Institution Press; Rev Upd edition, May 2000).) They include passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in 1975, a revision of the Johnson O’Malley Act to better educate Indians, passage of the Indian Financing Act of 1974, passage of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act in 1976, and the creation of an Assistant Interior Secretary post for Indian Affairs. Mount Adams was returned to the Yakima Nation in Washington State, and 48,000 acres of the Sacred Blue Lake lands were returned to Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. This was the very first return of land to the Indian Nations. During the Island’s Occupation second Christmas, Nixon signed papers rescinding Termination stating, “This marks the end of Termination and the start of Self-determination.”

Almost a month into the occupation, KPFA—and the other Pacifica Stations, KPFK in Los Angeles and WBAI in New York—broadcast the show Radio Free Alcatraz for 15 minutes a night to about 100,000 listeners. John Trudell was the voice from Alcatraz, covering Indian issues, interviewing residents, arranging talks on culture, fishing rights, the taking of Indian lands, and allowing the elders to tell the stories that had been passed down from generation to generation. This began a tradition of community radio that linked the Bay Area with the ongoing struggles across the country.

The Native college students would leave the island to attend their classes and to participate in founding the Ethnic Studies program in Berkeley and San Francisco State. They would return to Alcatraz on the weekends bringing the support of other students and community members. The negotiations dragged on into 1971 with the Government shutting off all electricity and removing the water barge which had provided fresh water to the occupiers. Three days later a fire broke out on the island. Several historic buildings were destroyed. The government blamed the Indians; the Indians blamed undercover government infiltrators trying to turn non-Indian support against them. Finally on June 10, 1971, armed federal marshals, FBI agents, and Special Forces police swarmed the island and removed five women, four children, and six unarmed Indian men. The occupation was over.

San Francisco was the City of Love, the third eye of the world, the place of prophecy. Rolling Thunder came to speak to the spiritual communities and they said he could speak if a Native woman would vouch for him. Patricia Clarke was the founder of an intentional community called the California Dreamers. As a Nez Perce woman she interviewed Rolling Thunder and found him to be a Medicine Person with sacred powers. He was then asked to speak at many gatherings of holy people in the City. The White Roots of Peace came to San Francisco and Mad Bear Anderson of the Mohawk Nation inspired Richard Oakes with his knowledge of the sacred wisdom of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Hopi Messengers, David Monongye and Thomas Banyaquaya, told the San Francisco Native Community about the time of Great Purification. Leman Brightman, founder of United Native Americans founded the first Native Studies Department in Berkeley. Richard Oakes inspired the beginning of the Native American Ethnic Studies Department at San Francisco State College. Many Alcatraz supporters would go on to teach in these new programs and others would join them. Don Patterson would teach Music, Dr. Bernard Hoehner would head the Native American Department from 1970 to the early 1990s. Vernon and Millie Katcheshawno were well known educators and activists. San Francisco State’s Student Kouncil of Indian Nations, or SKINS, was founded soon after the Alcatraz Occupation ended. Randy Burns and Barbara Cameron would found the very first Native American Gay organization, Gay American Indians (GAI).

While on Alcatraz and soon afterward many people were talking about the Ghost Dance Vision of the return of the Indian Spirit from the West Coast back to the East. The Navajos and the Cherokee talked about the “Long Walk” and the “Trail of Tears.” Many would overhear the words, “We should reverse the walks and take back our rights, our courage, and our lands.” This series of conversations led to the Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan from San Francisco to Washington DC. Gathering tribal people all along the way they joined together to demand recognition and empowerment from the US Government, the Department of the Interior, and the BIA.

One of the radio stations covering the Trail of Broken Treaties was a small community radio station in San Francisco. A member of the KRAB nebula radio community founded by Lorenzo Milam, KPOO was located on Natoma Street near 7th and Mission near the former Greyhound Bus Station where so many relocated Indians took their first steps on the streets of San Francisco. Chicken, Charlie Steele, and Tiger started a Native radio program that was called Red Voices. When Joe Rudolph and others from San Francisco State’s student Strike took over the station and made it the first Black-owned community radio station on the West Coast, they made a commitment to the Native Community: there will always be a show produced by Native People on KPOO. Red Voices covered the armed takeover of the Village of Wounded Knee, interviewing the warriors, asking for food and supplies, and announcing the benefits to raise money for the travel costs to get the supplies to South Dakota.

The years between 1973 and 1976 were some of the most violent in the history of the modern Indian struggle. 271 deaths occurred on the Pine Ridge Indian reservation, mostly of the traditional people who were trying to maintain their own religion and life ways.(8) Many of the American Indian Movement members were arrested, in jail, on the run, or being extradited. The Bay Area was the center for legal activities. The Wounded Knee Legal Defense Offence Committee (WKLDOC) raised monies, came up with defense strategies, and developed a network of pro bono lawyers to defend the young warriors who had been arrested. The Native American Solidarity Committee was a group of young people committed to support the rights of Indian peoples to their lands and their own governments. There were a lot of interesting conversations about the difference between solidarity and support going on with many of the young people outside the Native community to find out about their own backgrounds and the struggles of their own peoples. The Sami organization got a couple of supporters who found that the tribe they came from was indigenous to Scandinavia. A young woman of Irish descent took a trip to Ireland and became active in the Irish community.

The American Indian community was empowering itself by turning to the past, to the traditions and religions of their own Nations. Leonard Crowdog came to speak about re-establishing the practice of the forbidden Sundance in the Lakota Nation. Ruben Snake spoke of the ability of the Native American Church to cure alcoholism and drug addiction by returning to the old traditions. These and many other conversations resulted in the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978 to protect the participants. In the land of religious freedom it took an act of Congress to protect the Indians who wished to practice their own religion.

In the summer of 1974 the Movement activists left the Bay Area to join the Lakota Sioux in order to form the International Indian Treaty Council. The founding conference was on the Standing Rock Reservation. The founding document of the International Indian Treaty Council raised the conflict to the international level, calling upon the world’s peoples to join in recognizing the sovereignty of the Native Nations. The Treaty Council opened and maintained an information office in San Francisco to produce the Treaty Council News and to have ongoing interviews with the local Native Radio programs. Red Voices interviewed Oran Lyons, Phillip Deer, and Mad Bear Anderson on their way to the United Nations gatherings in New York and Geneva. The Hopi talked on the radio about fulfilling their prophecy by knocking on the door of the “House of Mica” (the UN in New York).

American Indian Center at 229 Valencia Street, 1983, a replacement for the earlier Center that burned down in 1969 on 16th Street.

Photo: Max Kirkeberg collection diva.sfsu.edu

The annual Thanksgiving Holiday became a day for ceremony, fasting, and prayer beginning with a sunrise ceremony on Alcatraz Island. The American Indian Center was relocated to Duboce and Valencia. It became a safe place to gather to plan benefits, to raise money for the lawyers, to have a meal together, and laugh and forget for a while the hardships of the people. In a little house around a kitchen table in San Francisco, a group of women gathered and talked about an organization to support the men and strengthen the women’s ability to survive. That organization was called Women of all Red Nations (WARN) which refused to be relegated to the end of the agendas and the back of the rooms in the women’s conferences and gatherings. “We cannot support the agenda that once again takes our children away from us to be raised by government child care centers. We have a different experience and a different history that also needs to be honored and respected.”

Bill Wahpepah founded and maintained the AIM for Freedom Survival School to teach our youngsters their own history without being told that they were extinct or of no value. Weavings were being rewoven to bring many peoples together. Vernon Katchshawno went to Mexico and found and met with the Mexican Kickapoo. He returned to Oklahoma and reintroduced his Mexican cousins to his family back in Oklahoma. The American Indian Movement sent representatives to stand in front of the International Hotel to prevent the evictions of the Pilipino elders. Teveia Clarke and her son were near the corner of the I-Hotel when a Sheriff on horseback tried to ride into the protesters. Teveia was a Nez Perce woman; her people developed the Appaloosa horses and bred them for color and stamina. She blew into the horse’s nose and chanted. The horse backed away, reared, and when the sheriff fell off, the horse stepped on his foot. “You shouldn’t mess with a Nez Perce woman if you are on a horse,” she said.(9)

Teveia’s son would stand on Haight and Ashbury selling Akwesasne Notes alongside others selling papers like the Oracle and the Berkeley Barb. The San Francisco Arts Commission was dragging their feet about supporting the Neighborhood Arts Program’s demands for cultural centers and culturally relevant arts for all people not just the elite supporters of the Symphony, Opera, and the Ballet. The American Indian Arts Workshop helped to found both the Mission Cultural Center in the old Shaft Furniture Store and Brannan Street Cultural Center (now SOMArts Cultural Center). There was a wonderful program called Comprehensive Employment and Training Act enacted in 1973 that paid a living wage to people who had not been able to be paid for their work before. Bill and Alberta Snyder taught music and beadwork. Ed and Madelyn Payett taught archery and the most beautiful ribbon work. Teveia Clarke and I were oral historians, talking story and developing programs for students after school and on the radio. Barbara Cameron and Sherol Graves were silkscreen artists and photographers. Jean McLean was the director who wrote the grants and ran the organization.

One of the demands from the Occupation of Alcatraz was the protection of sacred sites. In 1976 the California State Government passed AB 4239, establishing the Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC) as the primary government agency responsible for identifying and cataloging Native American cultural resources. One of NAHC’s primary duties is to prevent irreparable damage to designated sacred sites as well as to prevent interference with the expression of Native American religion in California. This commission was charged with protecting Native sites without adequate funding to do so. It has always been an honor and a privilege for Native women and men to volunteer their time and money to this organization. This has not prevented museums and universities from retaining human remains and grave goods in their collections. However the laws passed first in California helped to push forward the passage of the American Indian Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in 1990.

The Longest Walk began February 11, 1978, on Alcatraz Island. The Longest Walk was a brilliant organizing tool. Walking across the country kept everyone informed of all the issues across Indian country and connected the coasts with everyone in between. It hit all the high points: Pit River, Washoe territory, Western Shoshone, Big Mountain, Leonard Peltier’s incarceration. The walkers were the marginalized, the homeless, the abused, and the alcoholics who found that the prayers and the staffs of eagle feathers healed them and empowered them. Only 20 people have affidavits that they walked all the way and of those only 10 have survived. Red Voices radio carried reports from the Walk on every show. San Francisco heard where the walkers were and where they were going to be. Shoes and socks were sent on ahead of the walkers. The stories of the 11 bills in Congress to terminate all treaties with Indian Nations, and the stories of the young women sterilized by IHS programs without their knowledge or consent, were on the air in San Francisco. The People’s Temple had a benefit to raise money for the Longest Walk.(10) The churches and neighborhood centers raised the awareness of the community around the issues. The bills were all defeated and the Indian Health Service programs were investigated.

As a result of the Longest Walk Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) later in 1978. American Indian children had been removed from their culture and fostered or adopted into non-Native families at a rate greater than any other group. The passage of the ICWA stemmed the tide of the removal of the children. The American Indian agencies in the San Francisco Bay Area were in the forefront of advocating for and passing the Act. In the Courts of San Francisco the reasonableness of ICWA became the standard of how to treat all children in the foster care system. All children are placed in homes that are aware of the cultural traditions of the children and if possible within families of the same ethnic background.

The decade inspired positive change in the Native American community. However the struggle continues. The Winumum Wintu are fighting to regain their federal recognition so that they can protect their last remaining sacred sites from the rising waters of Shasta Dam. The Ohlone are returning to San Francisco to take their rightful place as the caretakers of the lands and waters of the area. The United Nations passed the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples and of the four nations who voted against the passage New Zealand, Canada, and the United States remain opposed. We look forward to a time where the generational trauma can be healed by acknowledging what happened to the Native People here and requesting their wisdom in caring for the waters, the lands, the plants, the animals, and the people.

Notes

1. Formed in 1969 in Los Angeles, California, by brothers Patrick Vasquez (bass and vocals) and Lolly Vasquez (guitar and vocals), the name Redbone itself is a joking reference to a Cajun term for a mixed-race person (“half-breed”), the band’s members being of mixed blood ancestry. In 1973 Redbone released the politically oriented “We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee,” recalling the massacre of Lakota Sioux Indians by the Seventh Cavalry in 1890. The song ends with the subtly altered sentence “We were all wounded ‘by’ Wounded Knee.”

2. Julie Davis, “American Indian Boarding School Experiences: Recent Studies from Native Perspectives,” OAH Magazine of History 15 (Winter 2001).

3. Alison R. Bernstein, American Indians and World War II: Toward a New Era in Indian Affairs (University of Oklahoma Press: 1999).

4. “The Relocation Act of 1956, resulted in more than half of the 1.6 million Indians in the U.S.A. to relocate to urban centers, signing agreements to not return to their respective nations/reservations in the future.” Redhawk’s Lodge. http://siouxme.com/lodge/land.html (accessed July 23, 2010).

5. “Sterilization of Native American Women.” http://www.ratical.org/ratville/sterilize.html (accessed July 23, 2010).

6. “Reies López Tijerina and the Tierra Amarilla Courthouse Raid,” Southwest Crossroads Spotlight, http://southwestcrossroads.org/record.php?num=739 (accessed July 23, 2010).

7. Bradley H. Patterson, Jr. The White House Staff: Inside the West Wing and Beyond (Brookings Institution Press; Rev Upd edition, May 2000).

8. There are many sources to understand what happened during that time. Two good ones are Peter Matthiesson, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse (New York: Viking Press, 1983), and Stephen Bain Bicknell Hendricks, The unquiet grave: the FBI and the struggle for the soul of Indian country (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2006).

9. See Estella Habal’s essay “Filipino Americans in the Decade of the International Hotel” in this volume for more information on the struggle to save the International Hotel.

10. See Matthew Roth’s essay “Coming Together: The Communal Option” in this volume for more on the People’s Temple role in activism.

by Mary Jean Robertson, from her essay "Reflections from Occupied Ohlone Territory," in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.

Find the book at City Lights!

Find the book at City Lights!