Revolutionary Art on Telegraph Hill: the Coit Tower Murals

Historical Essay

by Nancy Snyder

Originally published at counterpunch.org, December 15, 2023

1958 aerial view from south to north of Coit Tower, Alcatraz, and Marin County in the distance.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.5543

The story of Coit Tower begins in the City’s earliest days when San Francisco was accessible by ship to the rest of the country and the world. Being that Telegraph Hill, located in the northeastern corner of the City, had the most advantageous and panoramic 360-degree views of San Francisco Bay and its neighboring five counties, in 1849 Telegraph Hill served as a signal station, relaying the news of the incoming ships to San Francisco’s business sector down the hill on Montgomery Street.

The wealthy socialite [[|Lillie Hitchcock Coit, born in 1842, consistently disturbed her wealthy socialite colleagues with her eccentric foibles. With the assured confidence that money and privilege brings, Lillie Hitchcock Coit, a denizen of North Beach and Telegraph Hill, flouted convention and loved her exuberant life of hunting and camping and helping the local firefighters whenever a fire erupted. Coit was also an inveterate gambler who wore men’s trousers to to gain admission to the males only gambling establishments. She was known to indulge in hard liquor accompanied by a cigar.

In appreciation of the City – that Lillie Hitchcock believed was the only city who accepted her eccentricity, when Coit passed away in 1929, she left San Francisco a third of her estate. It was a hefty sum of $118,000 that Hitchcock bequeathed to beautify the City. The San Art Commission president, Herbert Fleishhacker proposed that the memorial be built on Telegraph Hill—Lillie Hitchcock Coit’s stomping grounds for pleasure and business.

San Francisco appropriated $7,000 in additional funds to for an architectural design competition. Architect Henry Howard, from the esteemed architectural firm of Arthur Brown Jr., the firm that had designed San Francisco’s City Hall and the War Memorial Opera House, won the competition for his concrete, 212-foot tower. The monument would be placed on the highest point on Telegraph Hill at Pioneer Part; Howard’s design possessed a symmetrical simplicity that gave the sleek linear monument an Art Deco presence combined with a touch of classicism.

The idea to cover Coit Tower’s interior walls with murals originated from Dr. Walter Heil, Director of the San Francisco Fine Arts Museums. It was the beginning of the country’s Great Depression, artists and everyone else were out of work.

Dr. Heil petitioned the Public Works Art Project, one of the beneficial relief programs implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Coit Tower murals would be the inaugural project of the New Deal federal employment program for artists. Bay Area muralists Ralph Stackpole and Bernard Zakheim successfully sought the commission from the Public Works of Art Project in 1933. The Coit Towers murals would begin work in January 1934.

Dr. Walter Heil began to hire the other muralists needed for the Coit Tower project. They would be paid $25-$45 a week. The muralists were supervised by Bernard Zakheim and Ralph Stackpole and included: Maxine Albro, Victor Arnautoff, Jane Berlandia, Ray Bertrand, Ry Boynton, Ralph Chesse, Rinaldo Cuneo, Ben F. Cunningham, Mallette “Harold” Dean, Parker Hall, Edith Hamlin, George Albert Harris, William Hesthal, John Langley Howard, Lucien Lebaudt, Gordon Langdon, Jose Moya del Pino, Otis Oldfield, Frederick E. Olmstead Jr., Suzanne Scheuer, Edward Terada, Frede Vidar and Clifford Wright.

The muralists would be painting in the “fresco” method: a timeworn technique used for wall painting that was discontinued by the late 1600s for more expedient methods. The fresco technique starts when the master plasterer applies a thin coating of fresh plaster – mixed with a bit of lime – to the wall. The amount of plaster used is, about two feet by two feet, would be determined by how much the muralist planned to paint on that day.

After the plaster is applied, the muralist paints with a wet brush dipped into the dry color pigments painted directly on the fresh lime plaster. When the plaster dries, a chemical bonds the color pigments and the plaster together.

It was the Los Tres Grandes, or the Big Three, Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco, who revived the fresco technique. Los Tres Grandes began the Mexican mural movement in the 1920s when they were commissioned by the incoming government of General Obregón in 1920. Jose Vasconcelos, the incoming Secretary of Education, was asked by General Obregón how best to unite the Mexican people after the 1910 Mexican Revolution that saw the overthrow of Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz.

Vasconcelos recommended the painting of murals in public spaces—a tradition of their Mayan ancestors—to educate and motivate the Mexican people. Gone were any remnants of the European schools, where Rivera had studied, that excluded any image of political and cultural strife. Los Tres Grandes put Mexican history on the walls of government buildings, universities and libraries that instilled a sense of recognition to the masses of poor and indigenous people, who had been unrecognized for centuries in the political and arts spheres of Mexican life.

The unifying theme in the Coit Tower murals was Life in California. The muralists’ designs had been approved by the regional director of the Public Works Art Project. The murals would depict scenes of California industrial life in the urban and rural areas.

To varying degrees, the Coit Tower muralists were all activists in the movements for racial and economic equality and leftist political ideals that were expressed in their extraordinary work.

With great excitement and anticipation, the Coit Tower muralists began their work in January 1934. The artists all worked in a cooperative spirit; there was enthusiasm for beginning what would be one of San Francisco’s great artworks; and there was much talk about what was happening to Diego Rivera in New York. In January, 1934, Rockefeller ordered the destruction of Rivera’s masterpiece, Man at the Crossroads.

The previous year, 1933, Rivera had met with John D. Rockeller, Jr. in New York City. Diego Rivera decided to accept a commission from Rockefeller, for a grand mural in the lobby of the newly completed Rockefeller Center. (A commission that kept Rivera on the outs with the Communist Party, USA).

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and his son, Nelson knew of Rivera’s political sympathies. John’s wife Abby was a patron of Rivera and had purchased several of Rivera’s works from the Rivera Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The Rockefellers were aware of Rivera’s politics and knew they might be displayed as greedy and decadent capitalists—but hired Rivera anyway.

Rivera’s plans for the mural, which would be called Man at the Crossroads, had been approved by Nelson and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The mural would be an expansive depiction of contemporary social and scientific culture; the juxtaposition of capitalism, the New Deal and communism would be expressed.

When Man at the Crossroads was nearly finished, Nelson and John D. Rockefeller took great offense at the inclusion of V.I. Lenin in the mural. The New York press had called Rivera’s mural “anti-capitalist propoaganda.” The Rockefellers had their pride and reputation to consider: capitalism would not be condemned in a mural by a Mexican communist artist, whom they had paid, on their property.

The Rockefellers demanded Rivera remove Lenin’s portrait, Rivera refused, and the Rockefellers did what they always do: Rockefellers pay someone else to carry out their dirty and unconscionable work. Man at the Crossroads was destroyed by the Rockefeller workmen in January 1934.

In late 1933, suspecting that Man at the Crossroads would be destroyed as the press further denounced the mural, Rivera had the foresight for the great photographer Lucien Bloch to take photos of his doomed mural masterpiece. The photos were black and white, but without them, Rivera would not have been able to repaint his mural.

In December, Rivera had approached the Mexican government he began at the end of the 1933, Rivera began a create a near replica of Man at the Crossroads, which would be called Man, Controller of the Universe, that resides in Mexico City at the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

A tremendous public cultural outcry ensued after this “premeditated art murder.”. Rivera was in Mexico, and replied that he “was not surprised” that Rockefeller destroyed his work. He was now in the process of replicating the masterpiece that would be called Man, Controller of the Universe.

Meanwhile, back at Coit Tower in January, 1934, as the destruction in Rockefeller Plaza’s underway and the muralists began their work, a newly formed cultural coalition of 350 artists and writers had formed the San Francisco Artists’ and Writers’ Union and joined the nationwide protest against the “premeditated art murder.”

The San Francisco Artists’ and Writers’ Union issued their statement when a protest against Rivera’s mural demise was held at Coit Tower. Muralist Maxine Albro began her speech with the observation that the ruin of Rivera’s work was not an isolated incident of any particular person or group, but reflected “an acute symptom of a growing reaction in the American culture which has threatened for years to strangle all creative effort and which is becoming increasingly menacing.”

As spring 1934 began, the political and economic tensions plaguing the City were about to converge. The Waterfront Employers Association, the company coalition of longshore employers, had refused to even hear the concerns of the International Longshoremen’s Association. The longshoremen’s proposals were simple: an increase in wages, hiring that would happen from the Longshoremen’s union hall and not from the very outdated hiring system that was corrupted by favoritism. The longshoremen knew that their union – independent from any company union – needed to be recognized.

By May 1934, the International Longshoremen’s Union voted to go on strike. On May 9, 1934, the Longshoremen did not shop up for work and the strike began. Imagine over 2,000 miles of commerce coastline that covered the ports of Seattle, Washington down to San Diego, California that had every longshoreman, the Teamsters on the waterfront who walked out in support of the Longshoremen, not showing up. Business did not stall, it stopped.

The Waterfront Employers Association remained intractable towards the longshoremen’s strike proposals. To channel the public’s anger towards the strikers, and away from the employers responsible for the longshoremen deciding to strike, another timeworn tool was utilized by the San Francisco press: a frenzy of red-baiting supported by the City’s politicians and orchestrated by the Waterfront Employers Association.

On Coit Tower, as work was winding down on the murals in May and June, the muralists were not spared the wrath of the red-baiting press. Certain that the artists were all communists and using government money to spread their message, the press photographers attempted to take pictures of the mural at night. The press photos that were published falsely edited to depict a hammer and sickle superimposed on the Library mural – lending the impression that the murals were all blessed with the Soviet emblem. And who knows what other communist propaganda were on the walls.

Furthermore, the right-wing propaganda press machine were certain that the Coit Tower muralists were sending some sort of secret signals down Telegraph Hill to the waterfront strikers. There was no evidence to this fantasy—yet for the press and its readers, it must be have been true: communists were devious, sneaky and it was just something they would have done.

To address the allegations of the press about the murals—and to ensure that the muralists were keeping to their previously approved upon mural designs—the San Francisco Arts Commission conducted its own tour of Coit Tower murals and came to the conclusion that the murals “were in opposition to the generally accepted tradition of Native Americanism.”

Therefore, the San Francisco Parks Commission, the local governing body for Pioneer Park,located, decided to close Coit Tower. The official July 7th opening date for the Coit Tower Murals was canceled. No future dates were chosen.

This unheard-of provocation by the City government enraged the artistic community—being justifiably apprehensive given the Diego Rivera mural destruction—and the San Francisco “patriots” being angered that such murals—rife with socialistic symbolism—existed at taxpayers’ expense.

There was a group of patriotic Bay Area artists, acting as a vigilante committee, ready to chip away the offensive murals that were shut out by a previous police blockade halfway up Telegraph Hill (the blockade against the artists and possible others “who might throw rocks, or give signals,” to the strikers on the waterfront.).

The Writers’ and Artists’ Union strategized a counter-offensive and established their own picket line around Coit Tower to protect the murals.

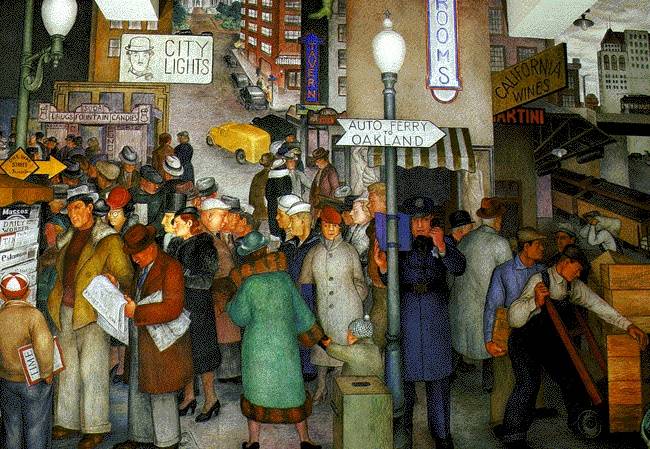

Coit Tower Mural — City Life by Victor Arnautoff

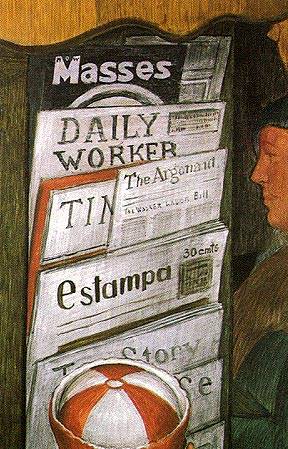

Summer 1934 arrived with the Coit Tower picket still in place. The SF Arts Commission found there were four mural panels deemed to be “socialistic.” The first errant mural was Victor Arnautoff’s City Life. There was a newsstand portrayed that had left wing publications, The New Masses and The Daily Worker but not the San Francisco Chronicle. The Artists’ and Writers’ Union replied that given The San Francisco Chronicle had been previously depicted Zakheim’s mural, Library, there was no need for further repetition in other murals.

The second offending mural was John Langley Howard’s Industrial Life, who had also depicted the left wing press: a miner was reading the Western Worker prominently depicted in front of an angry, and interracial, gathering of unemployed workers—who looked angry and aggressive. Other parts of Industrial Life made some on the Arts Commission’s observations appear to be self-censoring—given the recent events of Diego Rivera’s destroyed masterpiece.

Industrial Life included miners glaring at some tourists, who were standing too close to the tourists’ limousine and its chauffeur and lapdog. Next to this image, a broken down Model T Ford and a starving mongrel dog.

Next was Bernard Zakheim and his mural Library. There were more radical newspapers and a reader, modeled after muralist John Langley Howard, was reaching for a copy of Das Kapital by Karl Marx. Other library shelves included renowned proletarian authors Maxim Gorky, Erskine Caldwell and Grace Lumpkin.

However, it was the image of the hammer and sickle painted by Clifford Wight (a former assistant to Diego Rivera), that had angered so many conventional artists and press people into seeing red. The small hammer and sickle was a minor image in the mural that depicted the images of a steelworker and a surveyor. This was the only deviation in the approval process; Wight had submitted this change directly to the supervising muralist Arnautoff who had approved them.

The San Francisco Chronicle ran a scathing piece on July 3rd to further the red-baiting art scandal. Under the headline “Is this Red Propaganda? Murals on Coit Hint Plot for Red Cause.”

The story answered their headline query with this observation: “Perspiration has begun to bead the brows of members of the Parks Commission and Arts Commission, who are sore put to decide whether the daubings on the interior of the Coit Tower Memorial Tower are art or whether they are merely a grotesque rebellion of starved souls against the existing order.”

After extensive debate, the Arnautoff, Howard and Zakheim murals would remain unchanged; it was the Wight symbolism of the hammer and sickle that remain in contention. Wight and the Artists’ and Writers’ Union argued for “artistic integrity.” Wight had explained his reasoning for the symbol: the depiction of capitalism, communism and the New Deal nearly required such a symbol.

Regardless of the sound reasoning given to the Arts Commission, Wight’s hammer and sickle was removed.

After the Longshoremen’s strike was settled by arbitration and cargo began to be unloaded on July 27th, the red-baiting directed at Coit Tower began to subside. Coit Tower and its masterpiece murals would be open to the public beginning October 20, 1934.

Local journalist Junius Craven consistently demeaned the murals and the muralists throughout the spring and summer of 1934. Cravens observed that “There is something about fresco painting when it is applied to the walls of public buildings that seems to breed dissension…There have always been naughty little boys who drew vilifications on schoolroom walls when their teachers were not looking. Likewise, there have always been mischievous little artists who put something over while they were not being watched. Of such substance is history made.”

However, after the October opening of Coit Tower, Cravens changed his perspective. Cravens wrote with a lot less sarcasm and great appreciation, “San Francisco should be not only proud of [the Coit Tower] artists but grateful to them as well. And this not only for what they have given the city but also for the courageous way in which they tackled such a Gargantuan problem, fraught as it was with difficulties and discouragements, and licked it – knocked it out cold.”

On October 23, 2023, Coit Tower celebrated its 90th birthday with a formal reception from the City. It was a grey day that forecasted heavy rain which may have kept the party small, but the green parrots of Telegraph Hill, the official animal of San Francisco, made their presence known with their high-pitched squawking and flying overhead of Coit Tower.

Speaker of the House Emerita Nancy Pelosi, along with Aaron Peskin, member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors attended the celebration to represent San Francisco’s political wing.

What was more interesting was the appearance of two direct descendants of Lily Hitchcock Coit: Mike and Ian Coit. Mike Coit, graduate of San Francisco’s George Washington High School (Class of 1981) in the western part of the City, talked to the intimate crowd of birthday celebrants by relaying stories of his youth when he would attempt to impress his dates by driving to Coit Tower and show off his family connection: a move most likely to have brought some laughter to Lily Hitchcock Coit had she been around to witness her wily descendant.

Twenty years ago, Coit Tower underwent a tremendous restoration to its surrounding property, Pioneer Park and to the murals. For the probable future, its future maintenance and well-being is assured after being designated as a San Francisco landmark in 1984 and in 2008 when Coit Tower was included on the National Register of Historic Places.

Coit Tower has become a part of the popular cultural landmark. It is used as a backdrop for the Blue Angels—the Navy pilots who perform daring airplane stunts every October—and Coit Tower is a centerpiece in a few movie scenes (think of the high-stakes chase in Clint Eastwood’s The Enforcer, the Thin Man movies of the 1930s and 1940s and, of course, Kim Novak in Vertigo).

But forget about the movies and the Blue Angels’ wasteful use of fuel when they circle around Coit Tower every year. Consider the intent of the murals: to educate the public about how California lived during the Great Depression.

And, when you leave the Coit Tower murals, newly educated, you will hopefully be motivated to agitate alongside the young labor activists of today, and the immigrant rights activists, human rights and disability rights and LGBTQ rights—fulfilling the visions of the Coit Tower muralists.

Nancy Snyder is the Recording Secretary Emeritus of SEIU Local 1021. She has a long history of writing about labor issues and labor history and also writes about political literature.