Peoples Temple and the Destruction of the Fillmore: Difference between revisions

Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by Viva Donohoe, 2025'' 540px '''People's Temple at 1859 Geary in the early 1970s.''' ''Photo: California Historical Society'' The story of the People’s Temple is too often flattened into the image of one deranged man in dark sunglasses—Jim Jones, the manipulative and charismatic cult leader who deceived thousands. But rarely ar..." |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

In 1978, the group moved to Guyana, believing it to be the ideal location to realize their socialist, racially integrated utopia.(13) It was here that the Jonestown massacre occurred; in November of 1978, Jones urged his followers to commit "revolutionary suicide" by drinking a concoction of flavor-aid and cyanide. As Talbot writes, “As the grisly spectacle in Guyana was revealed, the Fillmore neighborhood was filled with wailing and tears. Ravaged by redevelopment, poverty, drugs, and crime, San Francisco’s black heartland reeled once more. Nearly every family in the neighborhood was touched by the loss of someone in Jonestown.”(14) As one can see, long before Jones’ followers drank the poison, their faith had already been broken by San Francisco—a city that bulldozed their homes, erased their culture, and left them searching for somewhere to belong. | In 1978, the group moved to Guyana, believing it to be the ideal location to realize their socialist, racially integrated utopia.(13) It was here that the Jonestown massacre occurred; in November of 1978, Jones urged his followers to commit "revolutionary suicide" by drinking a concoction of flavor-aid and cyanide. As Talbot writes, “As the grisly spectacle in Guyana was revealed, the Fillmore neighborhood was filled with wailing and tears. Ravaged by redevelopment, poverty, drugs, and crime, San Francisco’s black heartland reeled once more. Nearly every family in the neighborhood was touched by the loss of someone in Jonestown.”(14) As one can see, long before Jones’ followers drank the poison, their faith had already been broken by San Francisco—a city that bulldozed their homes, erased their culture, and left them searching for somewhere to belong. | ||

<big>'''Notes'''</big> | |||

1. Albert S. Broussard, [https://www.jstor.org/stable/25158348 “Strange Territory Familiar Leadership: The Impact of World War II on San Francisco’s Black Community,”] ''California History'' 65, no. 1 (March 1986): 18–25. | |||

2. David Talbot, ''Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror, and Deliverance in the City of Love'' (New York: Free Press, 2012), 54. | |||

3. (City and County of San Francisco 1948, 6). | |||

4. San Francisco Planning and Housing Association [SFPHA]. 1947. Blight and taxes. San Francisco: San Francisco Planning and Housing Association; Lai, Clement. 2011. “The Racial Triangulation of Space: The Case of Urban Renewal in San Francisco’s Fillmore District.” ''Annals of the Association of American Geographers'' 102 (1): 151–70. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.583572. | |||

5. Lai, Clement. 2011. “The Racial Triangulation of Space: The Case of Urban Renewal in San Francisco’s Fillmore District.” ''Annals of the Association of American Geographers'' 102 (1): 151–70. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.583572. | |||

6. David Talbot, ''Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror, and Deliverance in the City of Love'' (New York: Free Press, 2012), 54. | |||

7. Stein, Peter L, et al. [https://www.pbs.org/kqed/fillmore/learning/qt/pettus.html ''The Fillmore''], KQED, 11 June 2001. Accessed 30 Apr. 2023. | |||

8. Ibid. | |||

9. Fielding M. McGehee III, and Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. “Q134 Transcript.” Jonestown Institute, Accessed 15 May 2023. | |||

10. Stein, Peter L, et al. The Fillmore, KQED, op.cit. | |||

11. John R. Hall, ''Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History'' (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1987) | |||

12. Fielding M. McGehee III, and Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. “Q1057-5 Transcript.” Jonestown Institute, Accessed 15 May 2023. | |||

13. Melton, J. Gordon. [https://www.britannica.com/topic/Peoples-Temple "Peoples Temple"]. ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', 22 Feb. 2023. Accessed 30 April 2023. | |||

14. David Talbot, ''Season of the Witch'', op.cit., 54. | |||

[[category:African-American]] [[category:Redevelopment]] [[category:Churches]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Western Addition]] | [[category:African-American]] [[category:Redevelopment]] [[category:Churches]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Western Addition]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:39, 3 October 2025

Historical Essay

by Viva Donohoe, 2025

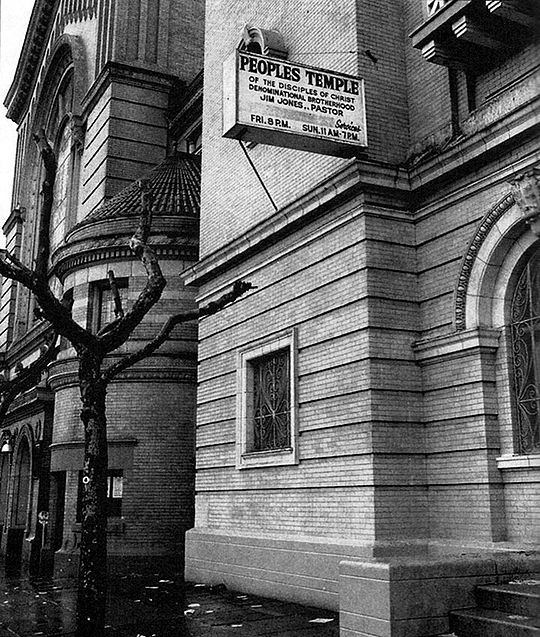

People's Temple at 1859 Geary in the early 1970s.

Photo: California Historical Society

The story of the People’s Temple is too often flattened into the image of one deranged man in dark sunglasses—Jim Jones, the manipulative and charismatic cult leader who deceived thousands. But rarely are the deeper structural conditions that made his followers vulnerable ever seriously examined. In San Francisco’s Fillmore District, where Jones’ church first gained traction, an earlier trauma had already destabilized the neighborhood’s residents. Decades of racist urban renewal policies—specifically the A-1 and A-2 redevelopment projects—had ravaged the Fillmore, displacing tens of thousands and gutting what had once been the heart of Black San Francisco. In the wreckage, Jones found a population desperate for stability, belonging, and responsive to his calls for racial integration and anti-capitalism. Understanding how Jones gained such a grip on the Fillmore, therefore, requires not just looking at the man behind the pulpit, but at the urban demolition and neglect that prepared the ground for his message to thrive.

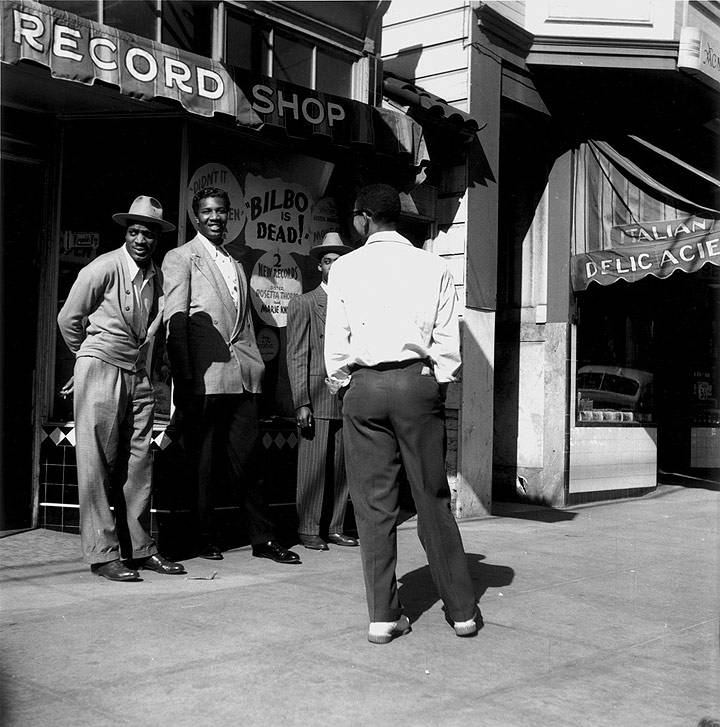

Melrose record shop at 1226 Fillmore Street, c. 1950.

Photo: David Johnson, via The New Fillmore

In the post-war years, the Fillmore district was a predominantly Black neighborhood, home to a rich bustling, cultural scene. The Great Migration, coupled with San Francisco’s growing defense industry, brought thousands of Black Americans to the city, most of whom landed in the Fillmore district. Out of this cohesion of Black migrants sprang up jazz clubs and dance halls, whose ever growing popularity earned the neighborhood the title, “Harlem of the West.”(1) As David Talbot writes in Season of the Witch, “The [Fillmore’s] streets were filled until the early morning hours with a parade of peacocks: men with diamond stick pins, satin ties, and long coats; women in slit dresses and furs. Adventurous white kids like Jerry Garcia would sneak into the Fillmore clubs and dance halls, this forbidden empire of cool, to hear the music they couldn’t find on Top 40 radio.”(2) However, what residents experienced as the vibrancy of urban density, city officials pathologized as symptoms of social and economic decay.

In the late 1940s, San Francisco housing planners viewed the Fillmore district's Black culture as a hub of urban immorality and a promise of future disinvestment. At a 1948 public hearing, State Senator O’Gara described the Fillmore as a “slum”: "[It] is the [district] where the worst blighted conditions exist, . . . the most overcrowded . . . the oldest houses, the most unsanitary conditions, the place where crime and juvenile delinquency and domestic difficulties, and all the other things that grow out of blight and slum[s] exist in the worst degree.”(3 The San Francisco Planning and Housing Association had also attributed the phys)ical deterioration backdropping the cultural scene—caused by the interlinked effects of the Depression, Japanese internment, and the postwar economic slowdown—to its Black demographic: "The Geary-Fillmore District. It’s not white. It’s gray, brown and an indeterminate shade of dirty black.” wrote on report.(4) It was this racist logic which inspired the A-1 and A-2 redevelopment projects of the subsequent two decades.

Geary Boulevard corridor looking west from Laguna, August 1961.

Photo: San Francisco Redevelopment Agency

In the early fifties, the A-1 redevelopment project strangled 30 blocks of The Fillmore, bulldozing housing, and displacing thousands of residents. Nightclubs went silent, Black churches relocated, and more than twenty-five thousand residents fled.(5) Jerry Garcia, the “adventurous white kid”’ who once snuck into jazz halls in his youth, sang in the sixties “Nothin’ shakin’ on Shakedown Street, used to be the heart of town.”(6) With A-2 project came the reconstruction of Geary Street; what was once a mom-and-pop shop lined road was turned into an eighth throughway zipping white commuters from their affluent neighborhood downtown. A-2 took control of another 30 blocks, uprooting an additional thirteen thousand people and shuttering thousands of more businesses.(7) As Talbot writes,

The city called it urban renewal. But to residents of the Fillmore, it was “Negro removal”. The Fillmore was the heart of black San Francisco, and redevelopment tore it out. The Harlem of the West now looked like a war-ravaged city, pockmarked with empty, rubble-strewn lots, shuttered storefronts, and dreary street corners inhabited by lost and wasted men. . . As the wrecking balls turned the Fillmore into a wasteland, an ugly spirit began sweeping the streets.

By the mid 1960s, the redevelopment project was succeeding in its implicit goal to stifle the Black community, and its explicit goal of creating an economically viable area.

In 1965, Jim Jones relocated the Peoples Temple to San Francisco when redevelopment forced Black Fillmore residents into harsh economic conditions and shaped a collective hopeless psyche. This psychological state made them more amenable to Jones' agenda. As one former resident notes, “[Jones] came into a community that needed to have a sense of belonging. For people who needed to come together. People who were broken…People were desperate for solutions. People needed something to follow. Jim Jones was a solution. He was something to follow.”(8) The People’s Temple established a permanent facility in San Francisco on Geary Boulevard. For the city's most marginalized community, it was heartening to have a man like Jones, who, on top of his charisma, vowed to heal Fillmore's “violence, and its crime, its disorderliness, its racism.” In his early sermons, he recognized the Fillmore as a “prison in itself” and asked the congregation, “don’t you feel like you’re in prison. Don’t you feel like you’re not free?”(9) The Black San Franciscan population was incredibly receptive to Jones’ doctrine of socialism, Christianity, and racial integration, which he tactfully framed as counterforces to the evils driving bulldozers through the Fillmore. After planting roots in the city, the church following grew from 300 to 3,000.(10)

The reverends Cecil Williams (Glide Church) and Jim Jones (People's Temple) at an anti-eviction rally at the I-Hotel, January 1977.

Photo: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons

Jones’ grip on the Fillmore neighborhood can also be traced to the symbolic weight he gave the neighborhood in his sermons. He folded the Fillmore into cultural narratives familiar to Black American churches, especially the recurring biblically rooted theme of an escape from Babylon to the Promised Land.(11) These Black migration stories often begin with images of suffering and escape. Jones used this to cast the Fillmore as a modern-day Babylon or Egypt. “We don’t like Babylon, we don’t like dictatorships,” he declared. “We’ve got to get out of Egypt... out of Babylon.” The Fillmore, he said, was a “world of fire,” and San Francisco “a miserable mess.”(12) Racism, poverty, and capitalism—the sins of American society—were believed to contaminate the People’s Temple. “We feel dirty sitting in America,” he preached. The blight of the Fillmore was not only physical; it was moral and spiritual. The only escape, Jones claimed, was to leave not just the neighborhood—nay, the country—and build their own “Promised Land” abroad.

In 1978, the group moved to Guyana, believing it to be the ideal location to realize their socialist, racially integrated utopia.(13) It was here that the Jonestown massacre occurred; in November of 1978, Jones urged his followers to commit "revolutionary suicide" by drinking a concoction of flavor-aid and cyanide. As Talbot writes, “As the grisly spectacle in Guyana was revealed, the Fillmore neighborhood was filled with wailing and tears. Ravaged by redevelopment, poverty, drugs, and crime, San Francisco’s black heartland reeled once more. Nearly every family in the neighborhood was touched by the loss of someone in Jonestown.”(14) As one can see, long before Jones’ followers drank the poison, their faith had already been broken by San Francisco—a city that bulldozed their homes, erased their culture, and left them searching for somewhere to belong.

Notes

1. Albert S. Broussard, “Strange Territory Familiar Leadership: The Impact of World War II on San Francisco’s Black Community,” California History 65, no. 1 (March 1986): 18–25.

2. David Talbot, Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror, and Deliverance in the City of Love (New York: Free Press, 2012), 54.

3. (City and County of San Francisco 1948, 6).

4. San Francisco Planning and Housing Association [SFPHA]. 1947. Blight and taxes. San Francisco: San Francisco Planning and Housing Association; Lai, Clement. 2011. “The Racial Triangulation of Space: The Case of Urban Renewal in San Francisco’s Fillmore District.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102 (1): 151–70. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.583572.

5. Lai, Clement. 2011. “The Racial Triangulation of Space: The Case of Urban Renewal in San Francisco’s Fillmore District.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102 (1): 151–70. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.583572.

6. David Talbot, Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror, and Deliverance in the City of Love (New York: Free Press, 2012), 54.

7. Stein, Peter L, et al. The Fillmore, KQED, 11 June 2001. Accessed 30 Apr. 2023.

8. Ibid.

9. Fielding M. McGehee III, and Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. “Q134 Transcript.” Jonestown Institute, Accessed 15 May 2023.

10. Stein, Peter L, et al. The Fillmore, KQED, op.cit.

11. John R. Hall, Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1987)

12. Fielding M. McGehee III, and Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. “Q1057-5 Transcript.” Jonestown Institute, Accessed 15 May 2023.

13. Melton, J. Gordon. "Peoples Temple". Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 Feb. 2023. Accessed 30 April 2023.

14. David Talbot, Season of the Witch, op.cit., 54.