Miné Okubo: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Ccarlsson moved page Mine Okubo to Miné Okubo |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 14:26, 26 September 2025

Historical Essay

by Hayden Douglas Gunter, 2025

Miné Okubo works on her illustration for a camp illustration during internment.

Photo: courtesy Japanese American National Museum

Miné Okubo was a victim of the American Japanese internment camps during World War II. During her time imprisoned in the camps, she documented her experience and then published her work in a graphic memoir, “Citizen 13660” in 1946. Her work illustrates the hardships and dark times that Japanese Americans went through after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Okubo was born in Riverside, California on June 27, 1912. Both of her parents were immigrants from Japan. Her mom was a painter and calligrapher, while her dad was a gardener. Her parents helped and encouraged her to form a great appreciation for art. (Creef, 2004). Okubo went to Riverside Community College and eventually to the University of California, Berkeley. There she earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree in art.

Okubo took part in several art projects in the Bay Area, creating mosaics and frescoes for the Federal Art Project. She was also able to work with Diego Rivera, the famous muralist, in the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island. (Creef, 2004). These were major steps in her art career. San Francisco at the time was a place that influenced artistic ability, making it perfect for Okubo. Being there, Okubo was exposed to many big names in the art industry and different artistic movements. The artistic opportunities in the city were endless. Through the community and environment there, Okubo took major steps as an artist and learned how art could communicate deep messages within it. (Lim, 2004).

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, changed the lives of every American, especially those of Japanese descent. The attack initiated Executive Order 9066, which ordered every Japanese American to be sent to internment camps within the country during the war. This was due to the government stereotyping all Japanese people and being afraid that they are spies or traitors. Okubo was one of over 110,000 Japanese Americans who were transported away from their homes. (Stanutz, 2018). Okubo was first sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center near San Francisco but was later relocated to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah. While in the internment camp, Okubo recorded her experience through her graphic memoir. Her book provides a raw, uncut resource of exactly how the camps were. She did this by providing many drawings throughout the book to go along with the text to add a grander reading experience.

Waiting in lines at the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, 1942.

Drawing by Miné Okubo, courtesy Japanese American National Museum

San Francisco played a major role in Okubo’s life both before and after the internment camps. Not only was the city very influential and beneficial for her art career, but it also hosted one of the largest Japanese American communities in the country. After the internment camps and witnessing the good, the bad, and the ugly, Okubo had mixed feelings around San Francisco. Before the war, the city was home to Japantown, where many Japanese Americans resided and kept traditional and cultural customs alive. And then during the war, so many Japanese Americans were taken from their homes. Okubo saw Japantown as a reminder for both what was lost and as a symbol of cultural resilience. (Creef, 2004). Through Okubo’s artwork, she was able to connect many people of different cultures together.

Okubo returned to California after the war, where she continued with her artwork. She would use hints of San Francisco in her art, more than likely reminiscing on her previous way of living. The city represented a place of origin as well as transformation, encouraging her message of resilience and identity. (Stanutz, 2018).

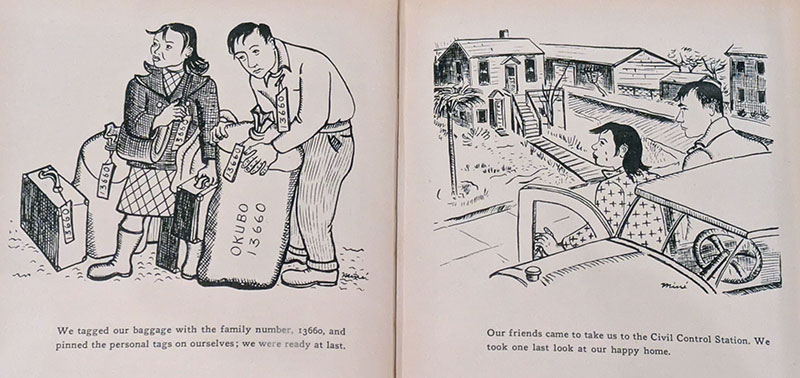

Obuko’s memoir, “Citizen 13660,” shows Obuko’s artistic skills but also serves as a historical resource as to what Japanese Americans were put through. Obuko was able to communicate what it was like to live in the camps through her illustrations. She used pen and paper to give a sense of what reality was like for her and the other thousands of Japanese Americans during this horrible time of the country. Her ability to combine images with text elevated her memoir for its profound insights, and was widely applauded. She was able to humanize the experience to create emotions in the readers through empathy. (Stanutz, 2018).

Panels from Citizen 13660.

The book was introduced as evidence during the Redress Movement in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. This act apologized and provided reparations on behalf of the country to all Japanese Americans who were placed in internment camps. Through her book, she has ensured that history will continue to be told and that future generations will learn and know about the internment camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. Okubo’s other works also embody resilience and identity. Okubo stayed strongly connected to the artistic culture of San Francisco and was a major influence on other artists and activists. (Creef, 2004).

Obuko died on February 10, 2001. Her legacy will not be forgotten, as her work is held at both the Smithsonian and the Japanese American National Museum.

Citations:

Citizen 13660. United Kingdom, University of Washington Press, 1983.

Elena Tajima Creef (2004) "Going Her Own Way: The Achievement of Miné Okubo," Amerasia Journal, 30:2, x-xxii, DOI: 10.17953/amer.30.2.h2072675m65rg221

Lim, S. G. Lin. (2004). "Miné Okubo: A Memory of Genius." Amerasia Journal, 30(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.17953/amer.30.2.18m38j762168368u

Stanutz, Katherine. "Inscrutable Grief: Memorializing Japanese American Internment in Miné Okubo's Citizen 13660." American Studies, vol. 56 no. 3, 2018, p. 47-68. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/ams.2018.0002.