Defending Islais Creek As City Expands: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Protected "Defending Islais Creek As City Expands" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite)) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 12:42, 18 November 2025

Historical Essay

by Stephanie T. Hoppe

Stephanie T. Hoppe is a former staff counsel to the California Coastal Commission and a great-great-granddaughter of Peter Seculovich.

Part 2 of Peter T. Seculovich in San Francisco

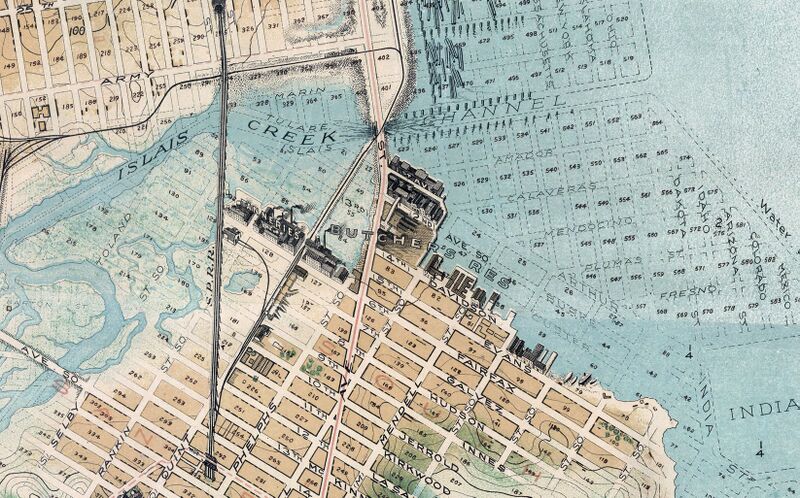

Gray and Gifford’s Birdseye View of San Francisco, 1868.

Image: David Rumsey Map Collection

Through these years San Francisco grew rapidly—to the west of downtown mostly housing and related small-scale commercial development, much more varied to the south. Industrial and institutional uses as well as housing filled or leapfrogged around Mission Bay and its surrounding marsh. Access to these southern reaches improved in the mid-1860s with the opening of the Long Bridge, which ran over a mile on wooden pilings from South Beach to the Potrero neighborhood, enclosing three-quarters of Mission Bay. With 100,000 cubic yards of rock removed from Potrero Hill to lower the grade and the Long Bridge extended nearly a mile more across the mouth of the small bay into which Islais Creek emptied, the Potrero and Bayview Railway ran horsecars all the way to the Bay View racetrack, built on the marshy ground thought beneficial for the horses. Excursion cars carried prospective buyers to view the offerings of homestead associations in the open land to the south of Bernal Heights.

The Mission Bay section of the bridge drew visitors with recreational amenities such as a fishing pier and a bathhouse with swimming access—or simply to stroll about and view boat races on the bay and people on the bridge. Itinerant food vendors walked the bridge and restaurants and saloons opened nearby on pilings of their own. Shipping continued to access Mission Bay through a 27-foot drawbridge.

The continuation of the Long Bridge across Islais Bay was more spartan, lacking both recreational amenities and a draw, thus cutting off shipping access to Islais Creek. Ship traffic likely was never intense. The repeated story that in 1862, “a Government schooner of forty tons, laden with hay, was burned at Franconia point” (Chronicle, 3/10/1899), may evidence the novelty of the use of the creek rather than the frequency. A contemporary testified that in 1861 a steamboat came up the creek and remained there for a month—perhaps because it ran aground. In that same year, schooners came up to a point on the creek at the time named Mazzini Street to fetch wood and hay (Sharpsteen). The width of the channel was reported variously as 70 to 200 feet at Franconia Landing; the tides could account for considerable discrepancy. In any event, even riding an incoming tide, it would have been a long, slow beat across two miles of looping channel against the prevailing westerly winds.

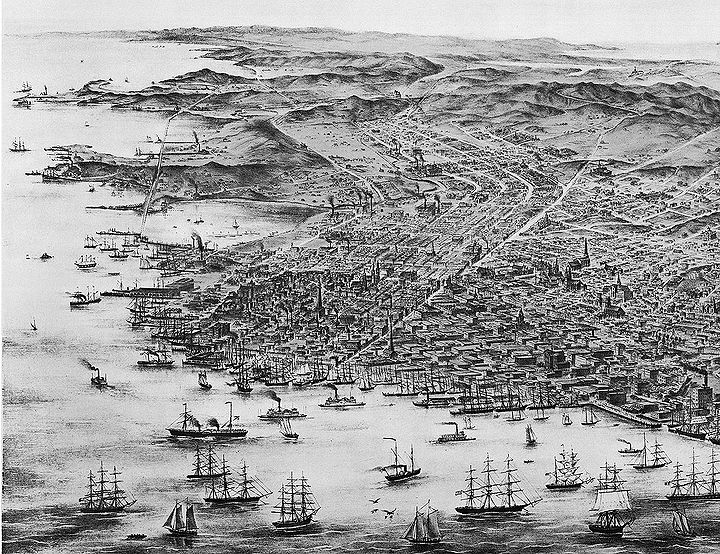

The Long Bridge also made it possible to move the slaughterhouse district from the north side of Mission Bay, where encroaching development brought increasing conflicts, to the south side of Islais Bay, despite the protests of the fewer and less influential residents of that area. In addition to multiple slaughterhouses daily bringing in hundreds of cattle, sheep and hogs and sending dozens of wagonloads of meat into the city, a complex of nearby industries made use of much of the remains: tanneries, glue works, fertilizer plants, soap and tallow works, a curled hair mattress factory using horses’ and cows’ tails. On Saturday mornings, consumptives gathered to drink the glasses of fresh blood recommended by physicians. The slaughterhouses were built partly on pilings in the creek and marsh allowing easy disposal of anything that remained.

The 1913 Chevalier map showing the location of the "Butcher's Reservation" on the southern edge of Islais Creek where its wetlands met the bay near 3rd Street.

Map: courtesy David Rumsey Map collection

Through the 1870s, Seculovich continued his real estate acquisitions, sometimes involving William Winter, a sign and ornamental painter who worked out of a building half a block from the fruit business on Washington Street where Seculovich worked as bookkeeper. Winter served as witness to the mark with which Gusina signed the 1863 deed for the property he sold to Seculovich. In 1875, Seculovich paid Winter $1,200 for lots 430 to 433 in Bernal Rancho Gift Map 2, which filled out his ownership of a block of 10 lots on present-day Crescent Avenue between Ellsworth and Gates streets. The purchase included a strangely long, very narrow parcel on the San Jose road to the west of Mission Street (12 ½ feet by 300 feet on the south line of the San Jose road, 600 feet west of Precita Place); perhaps this parcel completed another property he already owned. He bought other properties in what was sometimes called Precita Valley, an arc running northward along Mission Street from Cortland Avenue to Army Street, past his home at 3241 Mission Street, then easterly on Army Street across the lower slopes of Bernal Heights. He paid $1,100 for a 30-by-85-foot lot on the west side of Mission Street south of Kingston Avenue—a price that might indicate it was already developed and could produce rental income—as well as a lot more likely vacant, 25 by 114 feet, on Valley Street near Sanchez Street for $100 (Examiner, 2/24, p. 3, and 4/25, p. 3, 1877).

Although Seculovich’s Bernal Rancho properties remained grassland and marsh, urban infrastructure was coming closer. In April 1877, the Board of Supervisors approved “opening, establishing, grading, macadamizing” an extension of Fifteenth Avenue (present-day Oakdale Street) to connect the Potrero to the San Bruno road, including a bridge over Islais Creek (Examiner, 4/7/1877). At the time, “grading” referred to activity considerably more substantial than we might think today. San Francisco was originally a maze of hills and sand dunes where the only level ground came from filling the marshes and shallow edges of the bay. Achieving a desired grade for any particular street often required both cut and fill, sometimes to considerable heights and depths, and was carried out without regard to adjacent properties already developed, whose owners had to relocate their buildings or shore them up with retaining walls. According to an 1878 source,

In some cases, new stories were put under or upon old houses, which, though only one or two stories high when first built, are three or four stories high now. In the business part of the city, a large proportion of the houses were raised to conform to the Hoadley grade, and as many of them were large structures of brick, this raising was no small undertaking. A machine based on the principle of the hydraulic press, for lifting up houses, was invented and used for raising about nine hundred brick houses in San Francisco. (Hittell, p. 439)

Some years later, for the extension of Potrero Avenue and the San Bruno road,

From 25th to Army, 844 feet distance requires fill of 17 ½ feet. At grade to end of quarry in east side of Bernal Heights, a distance of 199 feet. To corner of 15th and San Bruno road, almost 2,000 feet, a cut up to 87 feet. Across the Islais creek marsh, fill 19 feet a little over 2,000 foot distance. Then 700 feet with a cut averaging 20 feet. (Examiner, 3/19/1891)

The Fifteenth Avenue extension was largely a matter of filling the marsh for a distance of three-quarters of a mile, and despite objections from some property owners, the project proceeded to bids and construction. The resulting embankment crossed Islais Creek to intersect the San Bruno road near present-day Esmeralda Avenue, a little to the south—upstream—of Franconia Landing and Seculovich’s original marsh properties, but downstream of his later acquisitions. At this point, the creek may have been as much as 80 feet wide, at least at high tide, but the embankment left only a narrow culvert for water to pass through. A floodgate stopped incoming tidewater altogether while allowing freshwater to continue to flow out.

We do not know how closely Seculovich followed the course of this project, but when he saw the result, he took alarm. In February 1879, he and other landowners petitioned the Street Committee of the Board of Supervisors “for such action as will effect the removal of obstructions to the navigation of Islais Creek, caused by the grading of Fifteenth avenue.” The committee postponed consideration of their request until following fiscal year, “when provision will be made for the removal of the obstructions.” In April, other property owners asked for drawbridges on Islais Creek “as by filling in of the creek, its navigation is obstructed and their property damaged.” In July, “a large number of property owners” “memorialized” the directors of the Potrero and Bay View Railroad, complaining that the Long Bridge, on which their cars ran, cut off navigation on the creek and deprived them “of their just rights, by means whereof the property above said bridge, on and near said creek, has been and is deteriorating in value and usefulness, and the owners of said lands injured” (Chronicle, 2/11/1879; Examiner, 4/29 and 7/1/1879).

Islais Creek wetlands along railroad trestle, 1920s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

Meanwhile, the Board of Supervisors “established grades” for Pennsylvania Avenue, west of the Long Bridge, setting the elevation for a proposed extension of that street southward across Islais Creek. A few months later, a group of property and business owners from Franconia Landing, including Seculovich, met in the offices of a downtown attorney and formed the Islais Creek Property Owners Association. The Chronicle reported “the earnest conviction” of John Reynolds, an acid manufacturer who was elected president, “that in the near future Islais Creek would be lined its entire raging length by substantial wharfs and the wharfs in turn be lined by stately ships and fishing-smacks.” The newspaper was less sanguine: “The present chief obstacles to this happy condition are the circumstances that the bottom of Islais Creek lies too close to the surface and that its surface is spanned by numerous bridges.” As for Seculovich—he “wanted the bridges torn down. He was equally anxious that no draw-bridges should be allowed either. As one of these bridges is used by the Bay View street railroad, there is the novel possibility that the street cars will have to ford the creek each time a crossing is made” (Chronicle, 11/25/1879).

In a more measured assessment, the Examiner reported that the property holders were looking to “have what is known as Islais Creek put to some practical use,” believing that one day the creek could be “the scene of busy traffic,” though “at present shallow and spanned by numerous bridges” (Examiner, 11/25/1879, p. 3).

Fully ten years had passed since navigation on Islais Creek was cut off by the Long Bridge, but the new association appointed a committee to take the matter to the Board of State Harbor Commissioners. At issue was effect of 1868 state legislation that declared Islais Creek from “Franconia Landing, on or near Bay View Turnpike to its outlet into San Francisco Bay, and thence easterly along the southerly line of Tulare street to the city water front on Massachusetts Street” a navigable stream. The law directed the Harbor Commissioners to establish the width to be maintained in the channel. Another provision prohibited building “any dam or bridge across the creek to the interference with navigation,” but allowed arch or drawbridges and licenses for ferries or bridges “when the public good demanded it.” Finally, the law specifically exempted the Potrero and Bay View Railroad Company from any requirement to put a draw in its bridge unless “the cost was borne by the interested parties who may desire the improvement.” The Harbor Commissioners’ powerlessness seemed clear, but in deference to the protesting landowners, they asked for legal advice. The following month, their attorney reported his opinion that the commissioners could not compel the railroad to put a draw in their bridge or maintain it at their expense (Chronicle, 11/29 and 12/10/1879).

Although the legal situation seemed clear, in an apparent change of heart, perhaps related to changes in membership, the Harbor Commissioners filed suit to declare the Long Bridge a nuisance on the grounds that Islais creek “from ‘time immemorial been a navigable stream,’ in the estuary of which the tide and ebb flow regularly, making it sufficient for ships to pass a distance of two miles from the bay to Franconia Landing, where a large population reside and manufactories are carried on.” The commissioners asked the court to compel the company to remove or substitute a draw for the present stationary bridge (Chronicle, 1/16/1880, p. 1).

The Board of Supervisors also saw a change in membership with the new year, and the new board took up the Pennsylvania Avenue extension. Discovering that vocal numbers of the affected property owners objected to the project, a committee of the board concluded that the work was not urgently needed and recommended the full board reconsider the contract awarded by the previous board. The committee also noted two new requirements in state law: first, that assessment of property to pay for improvements must be commensurate with benefits received. In the case of the Pennsylvania Avenue extension, it appeared that although the grading would render some parcels valueless, they would be assessed at the same rate as properties that were benefited. A second new law required assessments for public works to be collected and paid into the city treasury before work began (Chronicle, 1/20/1880, p. 4).

Seculovich and the other property owners took encouragement from these developments. At a meeting that month, the Islais Creek Property Owners Association elected Seculovich president in place of Reynolds, and he proposed a bill in the state legislature to (yet again) declare Islais Creek a navigable stream and also require the Board of State Harbor Commissioners to remove all obstructions to navigation as well as construct and maintain a draw in the Long Bridge. He also proposed a bill to repeal the state authorization of the Pennsylvania Avenue extension. Association members contributed $95 to pay his expenses to travel to Sacramento to lobby legislators in support of these bills (Examiner, 2/5/1880, p. 3).

Ten days later, Seculovich reported back to the membership that he found “a general misapprehension as to the real interests” of property holders among members of both the Senate and the Assembly. He had already scheduled further meetings with the San Francisco delegations to each house and relevant committees to push for the “clearing” of Islais Creek and against the grading of Pennsylvania Avenue (Chronicle, 2/15/1880). He also placed an ad calling for a public meeting:

Indignation Mass Meeting. Islais Creek and Pennsylvania avenue property owners respectfully and earnestly call upon all those affected by the Pennsylvania avenue swindle to meet together on SUNDAY, February 22, on Fifteenth avenue and vicinity of R street, and discuss the confiscation of their property and the repeal of the infamous act. By request of many. PETER T. SECULOVICH, President. John S Benn, Secretary. (Chronicle, 2/22/1880, p. 3)

Chairing the subsequent meeting, Seculovich explained that the assessments would exceed any benefits “as it would require at least $2,000,000 to complete the work,” and in addition, the project would interfere with the use of Islais Creek. Some of those present argued that the extension of Pennsylvania Avenue would “open a very large tract of land that is now shut out from all usefulness by Islais Creek and the marsh land adjoining it,” but in the end, the majority voted for Seculovich’s proposed resolution opposing the opening of Pennsylvania Avenue (Chronicle, 2/23/1880, p. 2).

A meeting a few weeks later at German Hall in south San Francisco, turned acrimonious, one person asserting, “Chairman Seculovich had made false representations before the Legislature as to the cost of the work.” Seculovich ruled him out of order, but others pressed for more details about the cost of the project and the rate of assessment. According to the newspaper account, “Chairman Seculovich insisted upon informing every one from his standpoint, notwithstanding persistent calls of ‘question.’” When someone suggested that Seculovich and others opposing the project had “an ax to grind” and if the assessments were too high that was due to the Board of Supervisors setting the street grade too high, which could be changed, Seculovich ruled him out of order and ordered him to sit down. He retorted by ordering the chair to vacate the office. At that point, most people left and the meeting ended (Chronicle, 3/8/1880, p. 3).

Still, before the end of April, due to the protests, with Seculovich “being the most active and energetic,” the legislature repealed the 1878 act authorizing the Pennsylvania Avenue project and the governor signed it into law. That fall, the Islais Creek and Pennsylvania Avenue Property Owners Association rewarded Seculovich with “a gold medal, gold-mounted eye-glasses and several other gifts.” To this day, Pennsylvania Avenue ends at Army Street—present-day Cesar Chavez Street—several blocks short of Tulare Street, which then as now forms the northern edge of the Islais Channel (Chronicle, 4/17 and 10/13/1880; Examiner, 10/23/1880).

All sources for this 10-part article appear at end of Part 10.