Poems in Street, Coffeehouse, and Print—The Mid-1960s

Historical Essay

by Stephen Vincent, originally published in "The Poetry Reading: A Contemporary Compendium on Language & Performance," edited by Stephen Vincent & Ellen Zweig, published by Momo's Press in 1981 in San Francisco.

Part II

The 1960s brought poetry back into the street, although not immediately. When I arrived at State, the City was quiet. Most of the activity generated by the Beats had worn thin. Few coffeehouses held readings. With the exception of readings at the San Francisco Museum of Art, sponsored by the Poetry Center, one could hear little public excitement. Except for Jack Gilbert, who had won the Yale Series of Younger Poets award in 1962 and who was hardly considered friendly to the Beats, the dramatic figures of the 1950s were in retreat or simply out of town.

Events in the City began to accelerate. The local Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized what became a series of demonstrations that gave San Francisco a tense and embattled spring. Thousands of people demonstrated at the Sheraton Palace Sit-Ins, the Auto Row Sit-Ins, and the Lucky Market Shop-Ins—and hundreds were arrested. The demonstrations marked the beginning of several movements that radically altered the feel of the City. An electricity in the air gave a new sense of attention to the variety of people and action in the streets. Language became prominent again. The local Chronicle and Examiner newspapers and the TV stations were totally out of touch with the meaning of events. People suddenly had an intense desire to hear a new language that would allow a clear grip on the events that were radically changing our lives.

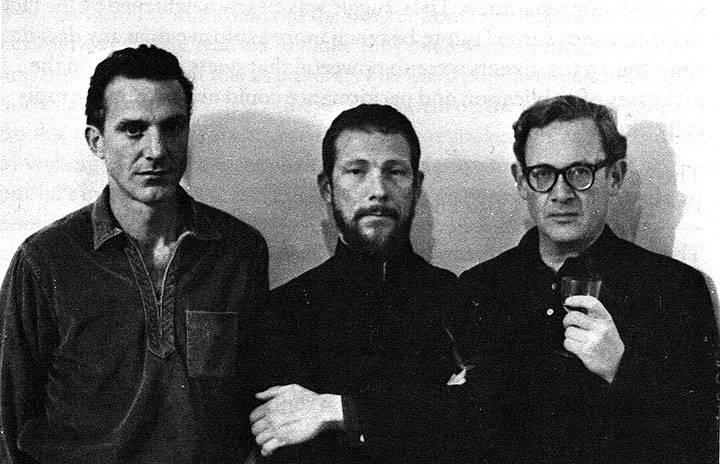

Lew Welch, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen before the Freeway reading in 1963.

Photo by Steamboat

The first poets to step into the breach were Lew Welch, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen-at the "Freeway" reading on June 12, 1963, in the Tenderloin at Old Longshoremen's Hall—folding chairs and squeaky hardwood floor. Jack Spicer, I was told, was sitting behind me, swollen red with drink, not taking matters too seriously, with a band of friends. But serious enough to come. Lew had done the advance work. Ralph Gleason, the late jazz columnist for the Chronicle, had devoted a whole column to Lew's work as a poet, how he had cracked up and gone off to the Trinity Alps for two years, how he had just come back. With a hall full of at least 500 people, it was a great way to reenter. Gary read what are now well-known Sierra poems in a quiet voice. Philip read his poems real fast, moving through his manuscript backwards, flipping pages left to right. It was too quick until he settled into a long poem about the City and the Sheraton Palace Sit-Ins-a great piece of rant and outrage, published eventually as "Minor Moralia." He juxtaposed the political events of the City against two high school girls discussing homework and dates on the bus, totally oblivious to the protests and arrests shaking the City. He had the audience riveted, hungry as we were for a real depiction of both our political aspirations and a direct sense of what was happening on the street. Whalen had immediately established himself as a troubadour of local truth. And then Lew came on; he read exquisitely, as he was then capable of doing, of his return to the City, coming down Highway 99, of bizarre encounters with old friends. Reading his Hermit Poems he juxtaposed the cosmic and harmonious aspects of mountain-stream-pebble formations with the incongruous run-ins of City life. With a charming and hilarious wit, he collided the urban and mountain world.

As a reading, "Freeway" was enormously important to what was to occur in the next few years. It was a declaration of space and position. The space was both the City and the country, with a definite West Coast fix. And the poet's position became that of public person. The reading put the poet back in the position of responding to the City in an actual way, letting the poetry move as the City does, responsive to the edges, to the corners, to the voices that flood our City lives. Built out of a democracy of eye and ear, the poetry would help create a culture where language would have a genuinely liberating function. There was definitely a politic and ethic to the new stance: It was the poet's community responsibility to make accurate perceptions, not false metaphor. The music emergent would be part of the cure, the liberation. Jazz was part of the medium: Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk were essential guides to how the language could break, lift, and move.

I remember Lew Welch saying this to me and some of my friends one night when we met by accident at the Juke Box, a now long-gone bar, near the corner of Haight and Ashbury. He had just finished giving a class on Gertrude Stein at the University of California Medical Center. What he said sounded fresh and available—so possible. He talked for three hours straight. I was high for three days. Suddenly all that time I had spent wandering City streets or through the Panhandle, marching in Auto Row picket lines, at Playland or the beach, the whole flow of information made sense, made a poetry possible. Taking the lead from Kenneth Rexroth's earlier work, Welch, Snyder, and Whalen began to provide an insistent example of poetry that constantly moved between the City, the coast, and the mountains, acknowledging the West as an authentic space in which to work.

For the next few years, the coffeehouse was primary home of the poetry reading, much as it had been early in the second half of the 1950s. In 1964 the Blue Unicorn was the base for much of the San Francisco activity. Located on Hayes Street, a couple of blocks above Masonic, on the other side of the Panhandle from the Haight-Ashbury, it was one of the few coffeehouses outside North Beach at the time. Gene and Hilary Fowler coordinated a weekly reading series there. Poets submitted poems, and then two or three were invited to read each week. Never fewer than twenty or thirty people made up the audience. When we students from State read, we were immediately aware of the challenge of reading in an off-campus situation.

Unlike the Orphic atmosphere and precise set-up of the Gallery Lounge, the Blue Unicorn was in many ways an extension of the street. (A motorcycle might be warming up outside during your first poem, or a drunk might come in off the sidewalk. The audience could be quite diverse; it was never quite clear where everybody came from. But that was the romance of the Coffeehouse: It was in the move of the City.) A tension rose between those of us who were students and the other poets, who were most often fiercely anti-academic "drop-outs." The going assumption was that anybody connected to a university or college was insulated from the "real" or "actual" world. Not getting a degree and writing "on your own" implied a definite purity. In spite of these tensions, the Blue Unicorn readings could be lively and loose. People cheered or laughed with lines that hit them or bantered back when the poet made off-hand remarks between poems. The real test was to read compelling work, to feel it strike a chord in the context of the City. That was the trigger behind the act. I'll never forget reading my own"495 Words for John Coltrane," a long sentence done while listening to "A Love Supreme," just writing down all the backyard action through my window—the colors of the laundry moving in the wind, the blue Clorox bottle hanging from the line, the singular woman sunbathing in another yard, the cats in their black, white, and orange colors hopping the fence—all done to the shifts in the music. The power I felt in the reading, the clarity of the silence between the lines, and the sense of the music and images registering in the audience were part of the possible wonder of giving readings at the Blue Unicorn. Even if it meant sitting through the dullest imaginable stuff (readings in coffeehouses were still novel enough to be a source of excitement to keep things going through the worst), performing was a quick, to-the-point acknowledgment of your work and a relief to the anonymous and isolated character of City living.

The Blue Unicorn became the second home for many of us. Along with Gene Fowler and Hilary Ayer, Ed Bullins, Jim Thurber, Doug Palmer, David Hoag, Steve Gaskin, David Sandberg, Norm Moser, among many others, read and often dropped in during the day to rap. Influenced by the populist example of Lew Welch, many of us shared a common desire to make a stronger contact with the local. Doug Palmer and Jim Thurber, sandwich-board style, took to writing poems for people on the street for money or barter, for which they were arrested on the charge of "begging" on the sidewalk in front of City Lights. Doug, with the support of Gary Snyder, who taught during 1964 at the University of California, Berkeley, began an IWW local for poets, musicians, and artists. For five dollars we got membership books and started a series of public readings at the loft offices on Minna Street, near Third and Howard. The combined impulse of much of the activity was to get the town back into poetry, music, dance, and good living, without which, as Lew once wrote, "The City is only a hideous and dangerous tough big market." Or, as Philip Whalen put it in "Minor Moralia,"

The community, the sangha, "society"-an order to love; we must love more persons places and things with deeper and more various feelings than we know at present; a command to imagine and express this depth and variety of joys, delights and understandings.

It was a call for a socially anarchistic utopianism with poetry leading the way that would resonate throughout San Francisco, Berkeley, and the West for several years.

With the "Freeway" reading began a process that led to a huge number of readings and an outpouring of books and magazines by local writers and publishers. The intensity of much of what happened might be seen in direct proportion to the growing resistance against the expanding Viet Nam War and the violence against civil rights activists. Although much of the work was not directly political during this period in Bay Area history, poets who were identified with both the hermetic "text" and the populist oral traditions assumed a much larger public stance. The 1965 University of California's Berkeley Poetry Conference, not long after a massive university spring teach-in against the war, had the effect of acknowledging the genuine relevance of the current work. The conference staged readings by most of the important local writers, including Snyder, Welch, Whalen, Duncan, and Spicer, among many others, and, in addition, Charles Olson and Robert Creeley who, though from the East, were part of the important Black Mountain College influence on the local scene.

Wittingly or not, the conference set the stage for the presence and arrival of a number of important books. In addition to White Rabbit Press and Auerhahn Books (then in the process of becoming David Hazelwood Books), publications were coming from Robert Hawley's Oyez (Press), Donald Allen's Four Seasons Foundation "Writing" series, and James Koller's and Bill Brown's Coyote Books. In 1965 alone, White Rabbit published Language by Jack Spicer and The Fork by Richard Duerden. Oyez presented On Out by Lew Welch and The Process by David Meltzer. Four Seasons issued Gary Snyder's Six Sections from Mountains and Rivers without End and Ron Loewinsohn's Against the Silences to Come. And Coyote Books published Dark Brown by Michael McClure.

Magazines and poetry broadsides were flourishing. Mimeograph was the hottest and cheapest way to get things out quickly. David Hazelton's Synapse, David Sandberg's Or, and Gino Clay's Wild Dog were three of the better known mimeo mags. Offset publications included Clifford Burke's Hol/ow Orange, Len Fulton's Dust, and Coyote Journal from the press of the same name. Many of the presses put out broadsides of current poems. In mimeograph format, they were given away as "free poems among friends" at demonstrations or on campus corners. Oyez (Press), and the San Francisco Art Commission did separate and beautiful series of letterpress broadsides of Duncan, Meltzer, McClure, Brother Antoninus (William Everson), and many others.

What happened among many of the writers at this time was a genuine crossover from the hermetic fine press format to more public forms and then back again. The work of Philip Whalen, for example, could be found in a small, beautiful, letterpress edition printed by David Hazelwood at the same time it was mimeographed in Synapse or handed out (by him) in hand-lettered, offset-reproduced broadsides. In a sense it was the best of all worlds for a poet: He or she could have the work printed exquisitely by Graham Mackintosh or David Hazelwood with a design and typeface ideally in accord with the full intention of the poem (although, as Robert Duncan argued, there could be huge disagreements there); or, with the new proliferation of presses and magazines, the work could be made widely and cheaply available. Behind the burst of activity was the desire to make the work as accessible as possible. An openness to the time stood in raw juxtaposition to the horror of the war and racial outbreaks in the civil rights struggle. It was a genuine reaching out to audience.

As disparate as the poets were, what unites most of the writing of this period is the human and sensual sense of exchange between language and audience. Jack Spicer's book Language of 1965 is, for example, the most open and accessible of all of his books.) The books, the magazines, the broadsides, and the ever-present poetry reading—which grew into the "Monster Reading Against the War" and finally the "Be In" festival—generated an echo effect between voice and text.

(Often poems read in public would influence whether or not they were published by an editor listening in the audience.) For the successful poet of the time, and for the devoted listener, the poetry established an urgent but confidently shared kingdom. You can hear it in the hand-lettered broadside:

DEAR MR PRESIDENT

LOVE & POETRY

WIN-FOREVER:

WAR IS ALWAYS

A GREAT BIG LOSE.

I AM A POET AND

A LOVER AND A WINNER—

HOW ABOUT YOU?

Respectfully Yours. Philip Whalen 10:III:65

The poetry began to gain a national audience. The reading scene for several of the poets moved to campuses and centers across the country. Grove Press and Evergreen Review (with the editorial influence of Don Allen), Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., and New Directions published books by Brautigan, McClure, and, eventually, Snyder, Whalen, and Loewinsohn. Although the college student textbook market may have been the strongest influence on the decision to publish these writers, it was one of those rare times in which a non-academically developed reading audience helped create the way for the national publication of poetry books. Many of the poets, including Joanne Kyger, Spicer, Welch, and Meltzer, could go no further than the small fine presses. Given the production standards and improved distribution of White Rabbit and Oyez, that mode could be considered preferable—and a way of staying true to the intentions of your work. (Many New York presses had a history of dull-looking poetry books whose designers had terrible reputations for trying to reshape spatially open poems into conventional stanza forms!)

For the younger poet, the presence of a relatively large reading audience in the mid-1960s made mimeograph or offset publication of a book by any of the new small presses as attractive as any other, and definitely quicker. Lenore Kandel's Love Book was printed offset and staple bound by Stolen Paper Editions in 1966. The attention it acquired caused an obscenity trial for Lawrence Ferlinghetti and City Lights Bookshop. Other popular books, without the same legal complications, were done by Keith Abbott, Eugene Lesser, Doug Blazek, John Oliver Simon, and Gene Fowler by other small presses. In 1966, Doug Palmer edited and produced Poems Read in the Spirit of Peace and Gladness, a 230-page anthology of work by thirty-two poets who had read at the IWW loft on Minna Street. It included work by Mary Norbert Korte, Luis Garcia, John Oliver Simon, and James Koller, among poets who are still active today. Along with being a successful local book, it was the fruition and full indicator of work influenced by the older, more established poets.

Looking back, it's hard to escape the impression of an era in which street, academic, and hermetic poets somehow magically joined to make the Bay Area light and wind vibrate with poetry in the face of violence and war. The urgency and popularity of public readings combined with the publication surge of books, many of which still hold their weight and power today, help confirm that impression. I say "impression" because I was unable to maintain my participation in that experience. In 1965, with the military draft breathing down my back, I joined the Peace Corps. Just before the Berkeley Poetry Conference I was sent to Kalamazoo, Michigan, for "training" to go to Nigeria, where I taught English and creative writing at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. It was a hard choice to make in the middle of the happening of so much.

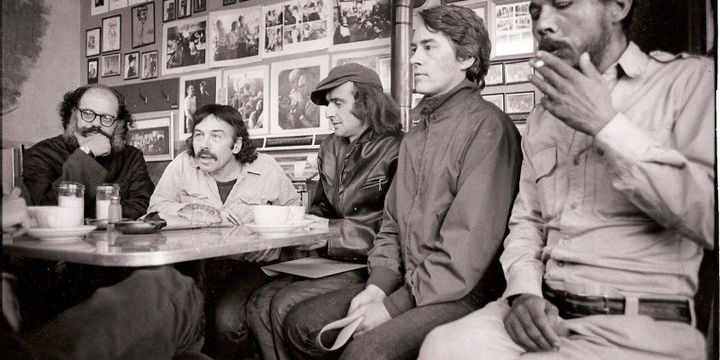

Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Bob Kaufman, and others at Caffe Trieste in North Beach, c. 1960s.