Working at a Defense Factory

I was there . . .

by Betty DeLucchi

Excerpted from Betty June: My Life During the Great Depression and World War II: 1926 to 1946, self-published, Pasadena, CA: 2020

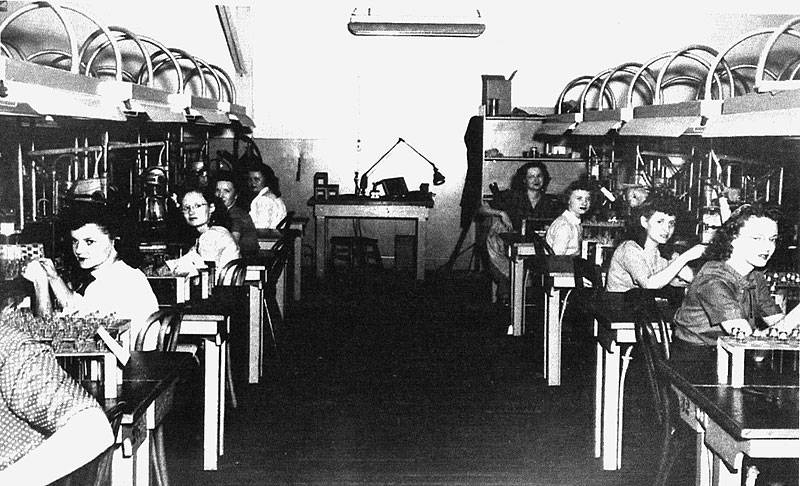

Women working at vacuum tube factory, early 1940s.

Photo: Betty DeLucchi

It seemed like every business and manufacturing firm in the San Francisco Bay Area was looking for workers. I applied to work at Eitel McCullough, a company in San Bruno. It was a factory where large radio-transmitter tubes were manufactured; the tubes were to be used on ships and submarines.

Several of my friends applied at the same time, so we went for our physical and aptitude tests together. I was hired as a spot welder, to manufacture grids which form the inner part of the tubes. I chose to work the night shift as it paid a slightly higher wage than daytime work. My father was pleased that I'd earn $2.25 an hour. I hoped to save money for college.

San Bruno was about 16 miles north of home. We traveled on the Southern Pacific Railway to go to work — the trains had a well-established system on the peninsula. We boarded at Redwood City station around 10:30 at night, and were often amused and fascinated by the cars. Everything was "blacked out" — the shades drawn over the windows and very little light in the interiors. We were not permitted to peek out even slightly by moving the window coverings. The only light emitted by the train was from the fixture on the front of the engine. But to view the interiors! It was like an adventure every night. Since all the better train cars were being used to transport troops, we got whatever could be found without too many flattened wheels. Sometimes the seats were wooden slats, sometimes they were covered with plush but worn red velvet; sometimes this fabric was on the walls as well. Often there were small vases on the walls, next to the unused gas light fixtures that hung between each group of seats.

We arrived in San Bruno just in time for our night shift to begin. On the station platform we waited for the train to pass on before crossing the tracks to the factory building and to our jobs. There was no light on the exterior but we could read the painted sign that said "Eitel-McCullough". Inside, we found our way to our separate departments. In the grid manufacturing section, workers were seated at long wooden benches, a welding machine mounted on the table in front of each worker. Using a form like a large spool, we wrapped platinum wire in several directions on it, and then applied a spiral wire so that it crossed each of the originally placed wires. Then we welded each juncture where the wires crossed and attached it all to a base. After learning how to do our job, we competed with each other to see who could make the best and the most.

The interior of the building was interesting and fun to explore. We liked to look into the other departments, especially where the glass blowing was done. Almost all the assembly workers were women, or men over the draft age; all the glass blowers were men. One of the lady workers became hypnotized by the big press machine that she was operating and was injured. She was not severely hurt but we became aware of the studies and safety precautions that must be taken by manufacturers.

This was the first time that women and girls wore pants in public. Up to then women were always seen in skirts or dresses. But of course pants were appropriate wear for work. It was a new experience for most of us.

It was also a new experience for the male workers we joined. Even in defense factories, women initially faced a hostile reception. But that changed rapidly as the men discovered their new colleagues' capabilities. Women knew they could do the jobs — tasks their mothers would have been surprised to see them do.

We also became aware of the great social changes occurring around us; they were dramatic and significant. There was a new mixture of ethnic groups, accents and customs. For the most part we took our places next to each other and did a great job.

Certainly we all shared a fear of the Japanese and Germans, as well as a desperate hope that we could win the war, so we understood each other and tolerated any differences.

My appetite for learning was strong. On the way home from my overnight shift at Eitel McCullough, I attended courses at San Mateo College. At 8:00am I was seated in the classroom for Music Appreciation or Basic English — simply because those were what was offered at that early hour. After class I would go home to Redwood City and sleep until time to head north again for my work shift.

While I was working at the defense factory, Mother let me know that she expected me to start paying rent for the bedroom I was sharing with Jean and the boys. This came as an unpleasant surprise.

After working nearly a year as a welder, I learned about a government-sponsored program for educating nurses. This offered to interested persons the opportunity to study nursing, to earn a degree and a chance to take the examination for a registered nurse license. Upon graduating, nurses were expected to become part of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps until the end of the war.

As soon as I learned about this program, I applied for entrance. I was accepted, and moved away from Redwood City to live in the student residence at a hospital in San Francisco.