THE MAYOR, THE CABBIES and the 84 DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION

Historical Essay

by Rua Graffis, United Taxicab Workers, 1996

Herb Silverman at Yellow Cab lot. Photo: Rua Graffis

The rumors weren't about the Democratic National Convention - everybody knew it was coming to town, that was a matter of public record. What the rumors were about was personal--our industry, taxis and how we would be affected by the coming of the Democrats; and the political aspirations of our Mayor, Dianne Feinstein.

Her current aspirations were Big Time: she wanted, in the worst way, to be the first woman nominated to "high office" by a major party. She wanted every single thing that happened to every single Democrat that came to San Francisco to be Absolutely Wonderful. If everything that happened to them while they were in the city was Absolutely Wonderful, maybe they would think she was absolutely Wonderful, and able to handle the job of Vice President of the United States. (3) Which made her worry about Absolutely Everything, including the possibility that one Democrat might have to wait one minute too long for a cab--and to think that she, Dianne, was personally responsible. And she worried that she might loose the nomination by that one vote. The answer to her was clear:

Make sure none of those Democrats had to wait one minute for a cab.

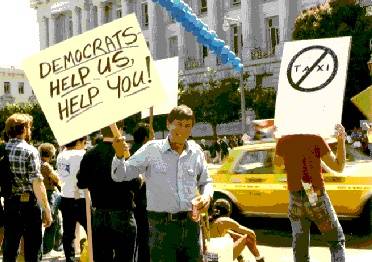

Cabbies demonstrate outside City Hall in 1984. Photo: Rua Graffis

Cabbies in 1984 demonstrating outside of city hall. Photo: Rua Graffis

For the sake of her political aspirations, she was willing to ruin an entire industry, for years into the future, because make no mistake about it (we certainly didn't), once those cabs got out on the streets, they would NEVER come off. We would be stuck with them -- forever. And stuck was a real condition to us: we already had more cabs than the city needed probably 60% of the time, what we needed was a way to regulate the number of cabs in relation to the city's need, but that wasn't one of the rumors we were hearing.

On March 22, 1984, the rumors became reality when Mayor Feinstein formally asked the Police Commission for 289 more cabs. (4,5) The bottom line on that "289 more cabs" meant a twenty to twenty-five per cent decrease in income to each cab driver--and that's a pretty good reason to go ballistic.

So Di Fi goes to the Police Commission in what she thinks is an orchestrated opening move to get some more cabs for the DNC, which will arrive in July. She probably only expected to get one hundred cabs.

In fact Roz Wyman, the "set-up" organizer for the DNC, coming into town for the first time in January, (and presumably unaware that this was already a hotly debated issue), told the cab driver who brought her in from the airport that even though she had never been to San Francisco before and knew nothing about the taxi business in town, she wanted one hundred more cabs for the convention. I know that is true due to total accident: I was that cabdriver. We had had a quiet ride in from the airport, but as we got off the freeway, she seemed to loosen up a little and I asked her if she was in town for business. She said she was here to get things ready for the DNC. I had read about her expected arrival in Herb Caen's column (6) just a couple of weeks before, and amazingly enough, remembered her name, so I said

"Oh, you're Roz Wyman aren't you?"

She was surprised that I knew her name (passengers are frequently surprised when cab drivers are literate, and au courant), and thus encouraged by her advance popularity, told me a little about her plans. Among other things, she said she had "Come into town to ask for 100 more cabs."

I tried to explain the long term results of that request, but she had her mind made up. I dropped her off at the St. Francis with a sinking feeling about what the next few months were going to be like for drivers fighting this kind of political pressure, and of course I told some of my friends about our conversation.

Roz Wyman was the second person to testify at the ill-fated Police Commission meeting, and she told this sob story of waiting for a cab at the Sheraton Palace in the rain on a Friday night for twenty minutes. (7) When Wyman got up to tell her sad story, pretending her recent experience was the reason for her request, there were a few drivers in the packed hearing room who knew the truth and hooted at her tale. But the Police Commission is nothing if not a political animal. Facts don't often get in the way of their decisions . They are appointed by the "reigning" mayor (a particularly appropriate adjective in Feinstein's case), and they serve at the mayor's pleasure--in other words they can be yanked off the Commission for voting the wrong way, and Di Fi handled her appointees with an especially short leash. (8)

The news travelled fast from one end of the city to the other that night, the basics told quickly as drivers pulled up next to each other at stop lights, or in more detail waiting at the airport or a hotel stand. By daybreak there were few drivers who didn't know what had happened at 850 Bryant the night before. Everyone was scared for their livelihood and pissed at the cavalier treatment of these political appointees, who would not, after all, be taking a pay cut for someone else's political ambitions.

The first ALLIANCE meeting was called at Dennis ' house, 249 Brussels Street, out in a working class neighborhood called The Portola. There was a sense of excitement that was tangible in the kitchen at 249 Brussels, an excitement born from the outrage of a bunch of people who felt that politicians were playing fast and loose with their lives. And we thought we could do something about it--that we MUST do something - because our lives depended upon it. So we put out flyers calling for all cab drivers to "Circle City Hall at noon on Wednesday." (14)

And over two hundred drivers responded, honking their horns and screaming "No more cabs No More Cabs NO MORE CABS!!!!!"

To Dianne Feinstein, child of privilege, we must have seemed a vision of her worst nightmare: the great unwashed, unruly mass, bursting in on her well-manicured, mayoral doorstep--and this was only March, the convention wasn't scheduled until July! Clearly this might only be the beginning of our rage. The feeling of our collective power--that we did not have to be victims of political whim--made us feel good about ourselves. We put out flyers calling for a meeting of all drivers on April 2 at the Retail Clerks Union Hall. Over two hundred drivers showed up and we formed the SAN FRANCISCO TAXICAB DRIVERS ALLIANCE. (17) For our first official action, we decided to hold a press conference on the steps of City Hall in tandem with our second "drive around" on April 11. Lacking the usual access to power that money might have given us, we realized we needed to be creative in presenting our case to the public and the power brokers of the city.

The next week we had even more drivers. The cacophony from hundreds of cab drivers' horns was spectacular and for us, exciting. We were on a roll! This time we were more organized and had secured all the necessary permits, including one for a bullhorn. John Hynes had the bullhorn and was verbally cranking up the crowd. About one hundred of us stood on the steps of City Hall, yelling along with the cab drivers who circled the building. In the midst of all the noise, a few hardy souls tried to give a press conference. John, bullhorn in hand, said, "Lets go in and talk to Feinstein!"

Before anyone knew what was happening we were in the door, crossing the stone floor of the rotunda, and up the stairs--maybe twenty of us--John leading the way with his bullhorn, all of us yelling "NO MORE CABS! "

The reverberation in that stone rotunda, the dome maybe three hundred feet over our heads, was something none of us will ever forget. We swept into Feinstein's office before anyone knew what was happening, aides scattered and flapped like frightened chickens, their normally subdued office galvanized by our energy--we were certainly nothing like the usual supplicants who were "impressed that we're in the Mayor's office" that they usually dealt with. To her credit, Dianne came out to meet us in person, there weren't even any security guards around at first--our entrance had been that unexpected. There is a wonderful picture of her surrounded by all of us cab drivers, shaking her finger at Eric and saying: "I won't be Mau-Maued by a bunch of cab drivers."

For the rest of its life, nothing with THE ALLIANCE was so much fun, but there were plenty of times when things were scary: when Eric, me, and Keith Raskin closed down the airport cab lot one day: we asked cab drivers not to pick up at the airport, and most of them honored the picket line. (20) Picket line duty is generally boring and dull, but several times, car loads of big guys with cameras drove past us...slowly...taking pictures...its amazing how menacing someone can seem, just taking your picture...and of course we never knew, over that long day, if they would come back the next time with more than cameras...or how they would use the pictures...or if we would have jobs the next day.

Eric chaired our next few meetings, held at THE FARM, a farm-in-the-city collective, nestled in between two freeways. Those meetings were pure pandemonium: three or four hundred crazed, furious cab drivers, and everybody wanting to talk at once, all you could hope for was that no fights broke out, and try to let as many people speak their mind as possible, and Eric was good at that. A lot of good people were turned off by the undisciplined nature of those first few meetings without ever sticking around to see how quiet they got in just a few short weeks. Those first meetings were crazy because they were the first time cab drivers had come together to try to change their lives in years, and everybody had something to say, were desperate to say it before they got shut up again.

Once it became clear that there were people (THE ALLIANCE Steering Committee) working to fight City Hall, our problem was the more typical one organizations face: finding enough members willing to do the work that needed to be done. Within a few months, we could fit everybody at a meeting into my living room. Life settled down to the day-to-day problems of running an organizing drive in the middle of a crisis (I've never been involved in an organizing drive that wasn't crisis driven). We put out a newsletter: John was the editor, and beside our own stuff, he reprinted labor articles from other sources as often as he could in an effort to ground us in the context of the larger labor movement (22). Katherine helped us find and hire a lawyer to fight the fifty permits Di Fi got the Police Commission to issue. Our lawyer was Dan Seigal, the former President of UC Berkeley's student body during the People' s Park strike.

As we got more organized, Garry McGregor was elected Chair. He invented our most successful type of action: the "Blitz Picket Line." In the case of cab drivers, what we had were a few people willing to walk a picket line, but the majority would be reluctant to be that visible, they would, on the other hand, be willing to "go somewhere else." So Garry had an inspiration: a few of us would make arrangements to call each other up at a specific time, say 4:00 PM tomorrow. At that time we would decide to meet at a specific hotel in twenty minutes with all our picket signs. In twenty minutes, we would descend on that spot, and go up and down the cab line, asking drivers "to serve another area of the city for the next two hours." and--PRESTO!--all the cab drivers would leave because there was always some place else they could be and make money. They could, by doing what came naturally (and not sticking their necks out), make a political statement. It was the perfect kind of protest for cab drivers: they could feel good about honoring the picket line and still not put their jobs in jeopardy. Our little group would walk a picket line in front of the hotel, with signs that said things like "DEMOCRATS: DON'T TAKE OUR JOBS! !

It drove the cops CRAZY--not to mention the hotels--and it especially drove the mayor crazy ... no one ever knew where we would hit next, or at what time. It was at once both guerrilla warfare and open war. And it was impossible to fight: by the time the cops heard where we were, we would be gone. We weren't officially calling a "strike," we were just "asking drivers to service a different area of the city for a little while."

And we won: not a complete victory, but a satisfying one, nonetheless--because of our actions, Di Fi only got 50 new permits from her Police Commission, with the promise of another fifty sometime down the line, and our lawsuit tied all of them up until after the DNC was over. (26) Of course she hated us for the rest of her tenure as mayor and went out of her way to make our lives difficult in every petty little way she could, from removing the fifty cent surcharge for use of the trunk (27,28), to getting the Police Department to add seven pages of penny ante, petty rules and regulations to the already ten pages of same that they used to harass our lives. She pressured the Airport Commission (also her political appointees, and some of them her personal friends) to limit the number of cabs allowed to wait at the airport to eighty-five. (29) Before she threw a hissy fit, we had room for about one hundred and twenty. Her justification was that we needed more cabs in the city--as though cab drivers would leave all that great money they were making in the city to go out to the airport and wait for three hours, and make no money at all. Ah, well, but that's life, isn't it? No pain, no gain....

At one point Feinstein was nearly ready to give us employee status by executive order, just to shut us up. We had huge discussions, but most of us had had the same experiences with the original cab drivers union: it was corrupt (there was even the widely believed rumor that the man who was reputed to be "only honest business agent" it had ever had, was "set up" and murdered close to the Marin Reservoir) . Katherine, a mainstream unionist, was adamant : we needed employee status, we had to become a federally recognized union, or it would never work. We voted not to explore that avenue with the Mayor. Katherine left. Herbie left when we lost our appeal at the Board of Permit Appeals . It became clear we couldn't permanently keep the new cabs off the streets.

I think it was worth it. If you are doing it because you can't live with yourself if you don't try to fight exploitation when you see it, if, for your own peace of mind, you need to try to even out power struggles when you run into them, and if you can live with the reality that you may not see results right away, maybe not even in your lifetime, then you might say "Yes, it was worth it ... what else was I doing with my life anyway?" THE ALLIANCE lasted for several years: amazing feat considering that a third of the industry turns over every year. Everybody always thinks "I won't be here next year." Unfortunately, when I hear cab drivers chant the magical phrase "I won't be here next year," it always sounds to me as though they think that if they get out of the cab business, they will magically enter a world of perfect employers who never take advantage of their workers.

THE ALLIANCE spawned a child before it died: the UNITED TAXICAB WORKERS. The UTW shares office space and gets encouragement from COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA 9410 at 240 Second Street. Without their moral and financial support, the UTW would have died of over work just like THE ALLIANCE did.

FOOTNOTES

1. Roberts, Jeffery, DIANNE FEINSTEIN, Harper Collins West, New York, New York; 1994. galley proof, pg. 145-146

2. Raine, George, "Tough Love," IMAGE Magazine, Sunday June 28, 1990, 5th edition, pg.i, 24

3. San Francisco Chronicle, March 20, 1984

4. Police Commission Hearing, transcript for March 22, 1984

5. San Francisco Chronicle, March 23, 1984

6. Herb Caen, San Francisco Chronicle, December 1983

7. Police Commission Hearing, transcript for March 22, 1984

8. Roberts, op cit. pg. 186

9. Conversations with Dennis Giannatassio, 1984

10. Interview, Herbie Silverman, April 23, 1995

12. Wiess, Mike, DOUBLE PLAY: THE SAN FRANCISCO CITY HALL KILLINGS. 1984 Addison Wesley Press

13. Miller, James, "DEMOCRACY IS IN THE STREETS": FROM PORT HURON TO THE SIEGE OF CHICAGO, Simon and Schuster, 1987; pp. 83, 87, 105, 112

14. Labor Archives, flyer, taxi collection

15. Weiss, op cit.

16. San Francisco Chronicle, March 29, 1984

17. San Francisco Chronicle, April 3, 1984

18. San Francisco Examiner, April 11, 1984

19. San Francisco Chronicle, April 12, 1984

20. San Francisco Chronicle, June 26, 1984

21. San Francisco Examiner

22. Labor Archives, taxi collection

23. Conversation with Dan Seigal, approximately April, 1984

24. Labor Archives, taxi collection

25. San Francisco Chronicle, April 18, 1984

26 San Francisco Chronicle, May 19, 1984

27 Conversation at UTW office, Cliff Lundberg, May 23, 1995

28. Chief's Taxicab Regulations, 1986

29 San Francisco Chronicle, June 14, 1984

30 Words by Ralph Chaplan, LITTLE RED SONG BOOK, IWW, Chicago, Ill.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chaplan, Ralph; LITTLE RED SONG BOOK, IWW, Chicago, Ill.

Miller, James; "DEMOCRACY IS IN THE STREETS": FROM PORT HURON TO THE SIEGE OF CHICAGO, Simon and Schuster, 1987

Police Commission Hearing, transcript March 22, 1984

Raine, George; "Tough Love," IMAGE Magazine, Sunday June 28, 1990, 5th edition

Roberts, Jeffery; DIANNE FEINSTEIN, Harper Collins West, NY, NY 1984

San Francisco Examiner

San Francisco Chronicle

Weiss, Mike; DOUBLE PLAY--THE SAN FRANCISCO CITY HALL KILLINGS. 1984 Addison Wesley Press

INTERVIEWS

Interview at Cafe Fanari, Mike Weiss, March, 1995

Interview in her home, Katherine Mann, April 13, 1995

Interview in his home, Herbie Silverman, April 23, 1995

Interviews by phone, Eric Chester, May 16, 1995, and June 1995

Interviews in at City Hall and in his home, Keith Raskin, May 30, 1995

Interviews at City Hall and by phone, David Frankel, May 30, 1995

Interviews by phone, Dennis Giannatassio, June, 1995