Riding the 14R From One End to the Other: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Protected "Riding the 14R From One End to the Other" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 17:22, 11 May 2023

I was there . . .

by Howard Isaac Williams, 2023

Somewhere in the last decade the MUNI 14L [Limited] (seen here) was rechristened the 14R [Rapid]. The latter description is certainly more aspirational!

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Few experiences demonstrate so vividly the decline of San Francisco and the City’s attendant disregard for its working class as a ride on the Muni 14R bus. And yet signs of hope, resilience and resistance also appear along the ride from the 14R’s southern origin at the Daly City BART station to its finish seven miles away at Mission and Steuart Streets downtown.

Like every 14R (for “rapid”), the bus is an articulated one, a 60-foot-long vehicle with an accordion like pivot midway on its length to bend when making turns.

On Friday morning, March 3, 2023, just before 9 A.M., I put my bicycle on the front rack of a 14R at the Daly City BART to ride all the way downtown. As I board, I ask the driver, a middle-aged Latino man, how long he expects the ride to be. He says about 55 minutes. I ride the 14R almost every weekday for most of its route but this day I planned to take the entire seven-mile ride. With the exception of one block downtown, the “R” travels the entire length of Mission Street, San Francisco’s longest and most historic street. The 14R is distinguished from the 14 by its limited number of stops, making for a faster ride. While the 14 stops at well over half of Mission Street’s 60 intersections, the “R” makes only 21 stops.

From Daly City BART where I board with a few middle-aged men and women, the R goes east on John Daly Boulevard uphill to Mission Street at the “top of the hill” where it makes its next stop. Here more adults get on along with a few children. Now, nearly every seat is taken. Almost all people on board are either Latino, Filipino or Asian American. By outward appearances and the time of day, most seem to be going to work. Outside, the restaurants and small shops represent the demographics of the passengers. A Chinese restaurant stands diagonally across the street from a Filipino one. Stands of fresh fruits and vegetables brighten the outside of bodegas selling foods from Mexico and Central America. These restaurants, along with barber shops and nail salons, laundromats and auto repair shops, medical and other professional offices, make this part of Daly City look much like the southern stretch of Mission Street in San Francisco. But we are not yet in the City. Going downhill, the R passes a Walgreen’s store flanking the corner of Goethe Street; in the many times I’ve been here, I have never seen the organized shoplifting that Walgreen’s blamed for the closing of 15 of its San Francisco stores.

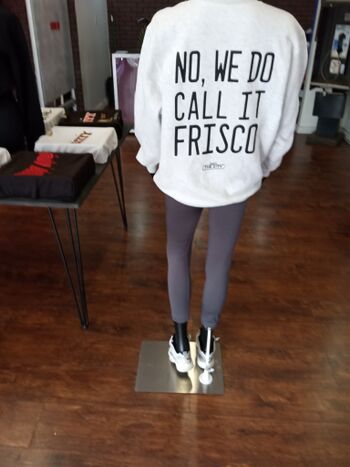

After passing Walgreen’s, houses appear, and the area becomes a mix of residential and commercial buildings. Then I see the first indication that we are in San Francisco. On the left (west), is a store window bearing a photo inscribed with the words “No we do call it Frisco.” While many San Franciscans adamantly say “Don’t call our City ‘Frisco’!”, others, including those born and raised in the City, especially in working class southern neighborhoods do say “Frisco.” The shop is called Made in the City and features shirts, caps and other apparel, all locally produced.

Another sign that we are in San Francisco is the bumpy ride. Experts disagree about the surface condition of San Francisco streets. Different studies report different conclusions with some claiming most San Francisco streets are well paved while others rank our road surfaces as among the worst in America. One fact is indisputable: Mission Street itself is in poor shape and almost every one of its 60 blocks in San Francisco is corrugated by cracks, potholes and asphalt that is just too old.

Although the R has made only two stops in San Francisco, it’s already standing room only as it barrels downhill toward Geneva Street passing more shops and houses and Longfellow Elementary School. Like all other public schools in San Francisco, this one—named after the 19th Century American poet Henry W. Longfellow—was closed during the pandemic’s lockdown. Unlike 44 other schools, this one—named after the author of “Paul Revere’s Ride”—dodged the S.F. School District’s renaming controversy.

The Excelsior Sculpture at Geneva and Mission.

Photo: Howard Williams

By the time the R stops at Geneva Street, this stretch of Mission is all commercial and will remain so as it passes through the Excelsior District. Like the rest of working-class San Francisco, the corner of Geneva and Mission was hard hit by the Great Recession of 2007—2009 (which seemed to last longer out here). Shops closed on three of the intersection’s four corners. Since then, new businesses opened. This recovery has managed to hobble through the pandemic and lockdown and is colorfully symbolized by the painted sculpture “Excelsior” on the intersection’s northwest corner.

A stout Black man with short salt and pepper hair gets on at Geneva. In the 1980s, 16% of San Francisco’s people were Black. The 2020 Census recorded only 5%. On this entire ride he will be the only Black person I see.

The bus is now even more crowded. Because the standees are so tightly massed, it is impossible to offer my seat to an elderly Latina about 10 feet away. Fortunately, someone else does. When I lived in Pakistan in the 1990s, the bus fleet was so plentiful that passengers never waited more than five minutes and when we boarded, we usually got a seat immediately or on the next stop. On my daily bus trips, I never saw a woman or elderly person standing in a bus. The dependability of the schedules, the speed of the service, the presence of bus conductors and the availability of seats contributed to a calm that organically inhibited criminal or even rude behavior.(1)

Most businesses in the Excelsior would be familiar sights in any American city. As the R hurries along Mission Street, it passes a multinational supermarket, a dollar store, community centers, tax services, laundromats, corner grocers, auto repair shops, bars, barber shops, medical offices and other businesses that would be easily found elsewhere.

Old bank building converted into a produce market, 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

But there are also places that distinguish this stretch from Anytown USA. The R passes by bodegas and botanicas selling foods, medicinal herbs and other Latin American products. In addition to Chinese and Mexican restaurants, there are places serving Filipino, Salvadoran, Vietnamese, Peruvian, Hawaiian and Thai food, some with the parklets that helped save San Francisco’s dining industry during the Lockdown. In the evening, congregations singing in Spanish will be heard from evangelical churches. International cash transfer services offer customers the chance to wire money to family and friends in Latin America, Asia, the Philippines and around the world. A few yards south of Geneva, a former movie palace recently repainted in blue and orange, has housed the Billiard Palacade, a spacious pool hall and diner since 1972. These businesses and their customers reflect the Excelsior’s population, once mostly Italian and Irish, now predominantly Asian and Latino.

Photo: Howard Williams

Midway through the Excelsior, the R passes an Art Deco building housing the Royal Baking Company. Above the entrance is a mural based on Leonardo daVinci’s The Last Supper. The bakery’s breads, cookies and pastries and its mural remind viewers and customers of both the Excelsior’s Italian heritage that goes back to the 1850s and the Latino residents who came here starting in the 1960s.

The iconic Royal Baking Company building dates back to the early 20th century when it was still a primarily Italian area. Today it is a Pasteleria, producing baked goods for a Mexican and Central American clientele.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Next door to the Royal is a Salvadoran pupuseria displaying a mural of the Roman Catholic Saint Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of El Salvador martyred in 1980 by a U.S. Government supported death squad.

At Silver and Mission, the R stops next to the Campus for Jewish Living, a major medical facility and community center for San Francisco’s Jewish population since 1872. When the light turns green, the R surges forward, going downhill toward the bridge crossing Interstate 280 and Alemany Boulevard. An experienced Muni operator can time the stoplights, cross the bridge and accelerate uphill to the next stop at Richland on the southwest slope of Bernal Heights. As the bus races over the bridge, I see murals flanking the sidewalk that portray Excelsior’s “international” street signs such as “Russia” and “Persia.” This mural project was organized and painted in 2011 by members of various Excelsior community groups.

After the bus reaches the northern side of the bridge, Mission Street becomes residential again. This is St. Mary’s Park, named for St. Mary’s College which was established here in 1863. One founding donor was the noted Black American abolitionist and entrepreneur Mary Ellen Pleasant (1815–1904). The esteemed school is now located in Moraga about 20 miles east of its original home.

Moving uphill quickly, the bus reaches its stop at Richland Avenue after timing all the lights from Silver and crossing the freeway that is becoming a border between Frisco’s working class southern “hoods” and the City’s gentrifying northern neighborhoods.

I notice trees more in residential neighborhoods like St. Mary’s Park but there’s actually at least one on almost every block of Mission Street. However in San Francisco, Mission is an exception. San Francisco’s urban forest is one of the smallest in America. Even in Los Angeles, trees cover a larger percentage of that city than San Francisco.

At the Richland stop, only a few people get on and off and the bus remains standing room only. Three people boarding are a Latina woman with two children. On this trip so far, I have seen a few kids and no dogs. But on most of my weekday afternoon rides on the R, dogs outnumber children. In this century, San Francisco’s dogs outnumber its children and as the Chronicle reported in 2022, our city is still “the nation’s most childless city.”

When he heard this and similar statistics, the archivist, activist and aphorist Greg Williamson (1954-2013), shook his shaggy, leonine head and responded: “Wait a minute, wait a minute. Last in kids and last in trees but somehow we’re the best city for dogs?! … Didn’t anyone ask the dogs?”

On the flat ground between St. Mary’s Park and the Holly Park neighborhood, the R passes a small commercial district. St. Mary’s Pub, a neighborhood bar at the corner of Crescent Street boasts the words “Since 1933” outside the door. After Prohibition ended in December 1933, St. Mary’s Pub wasted little time and opened a few dozen hours later.

Photo: Howard Williams

After passing by shops and restaurants, Mission Street turns downhill and is again lined with houses. Although the R is going downhill, the operator drives carefully. This stretch is probably the bumpiest and the bus rattles so much that it is difficult to read.

By the time we stop at 30th Street across from a supermarket, we have reached the commercial area at the southern edge of the Mission District on the western foothill of Bernal Heights and not far from the east side of Noe Valley. Now the R is passing along a stretch similar to the Excelsior’s commercial district but this changes at 24th Street BART. Here are open air markets at the BART plazas and on Mission Street’s sidewalks. Some are selling Latin American handicrafts while others sell manufactured products bought at discount.

Passing the BART plaza and then scanning Mission Street’s sidewalks, I see open air merchants hawking DVDs, CDs, tools and other items. Food cart vendors sell fresh fruits or grilled hot dogs. In 1990 when an Afghan friend and I walked along Mission, he remarked that the bustling crowds, tiny well stocked shops and especially the sidewalk vendors reminded him of the historic bazaars of Peshawar, Pakistan.

The Mission District (or simply, “the Mission”) is the city’s original neighborhood. Mission Dolores was founded in 1776 at 16th and Valencia (relocating later to its present site at 16th and Dolores). And over 4,000 years before that, Ramaytush Ohlone founded a village alongside Mission Creek, a fish-filled waterway meandering past meadows shaded by oak trees.

Signs reading “Calle 24 Latino Cultural District” appear along 24th Street, an area that does preserve much of San Francisco’s Latin American heritage. But there is some bitter irony in this as the Mission’s Latino population has decreased sharply in this century. Latino culture is still evident all over the neighborhood, but Latino people have been driven out by the gentrification seen along nearby Valencia Street and other parts of the neighborhood. By 2000, the Latino population had decreased to 60% of the Mission’s people. By 2015 it had fallen to 48%. A study predicted a drop to 31% by 2025 but the pandemic appears to have stalled the decline … for now.

With their working-class vibe, Muni buses plying Mission Street help maintain a proletarian aesthetic in the Mission. And, despite Muni’s drawbacks, many San Franciscans appreciate the transit system. “Muni Raised Me” is a colorful and provocative multi-media art event currently showing at SOMArts Cultural Center. Thirteen young artists—all born and raised in San Francisco—express grateful and unusual acknowledgements of the vital role of public transit in the life of the City. But the exhibit also protests the transformation of San Francisco with its curators describing it as “a sprawling project about a city that used to be.”

About midway through the Mission, an SUV abruptly cuts off our bus. The driver hits the brake and passengers grab straps and overhead rails to avoid falling. But one woman is slammed against the rear exit door prompting a robotic recording to command her to “Stand clear of the door.”

She manages to keep her feet.

“Are you okay?” several people chorus; she nods and says “Thanks.”

While the changes that have wracked San Francisco have hurt other neighborhoods, the losses feel more blatant in the City’s birthplace. Store closings in recent years include such landmarks as Mission Linen, Thrift Town, Siegel’s fashion store (where you could rent an authentic zoot suit) and Lucca Ravioli, the Italian delicatessen where you could buy authentic mozzarella cheese (the kind made from water buffalo milk). Except for Lucca, these and other closed stores have been trashed by graffiti. While some defend graffiti, the indiscretion by many “taggers” literally obliterates any authentic statements made by their peers, replacing message with pointless blight.

After pulling away from its stop at 16th Street, the R passes the American Indian Cultural District mural depicting San Francisco’s first neighborhood before the Spanish conquest. Ironically and sadly, this colorful artwork freely offered to us by the descendants of this land’s first stewards has been trashed by graffiti.

Two blocks later, we pass the Armory Building. Erected in 1912, the Moorish Revival styled bulwark served as a base for the National Guard during the 1934 General Strike. When the Armory closed in 1976, its closure was the beginning—little noticed at the time—of separating San Francisco from its longtime military heritage.

While crossing Division Street, the R passes under the Central Freeway (US # 101) and leaves the Mission. And here Mission Street is no longer traveling north-south; after Division it turns at an angle to run east-west. From its intersection with Division Street to its northern terminus at the Bay’s waterfront, Mission Street is technically in the South of Market District, a.k.a. “SOMA.” But in this part of the City, Mission is parallel to Market Street one block to the south and it often takes on the character of the nearby neighborhoods north of Market.

The first nearby neighborhood that influences this part of SOMA is Civic Center and several government offices stand along the blocks east of Division. None is more indicative of San Francisco’s “pay to play” culture of local corruption than the Department of Building Inspection (DBI) at 1660 Mission. When the local news website Mission Local published an article describing the “web of corruption” weaved by San Francisco public officials, no city agency was more entangled than DBI. Investigations by three local media report that DBI inspectors have accepted bribes and “loans” to grant permits for unsafe construction projects in the City.

Between 8th and 7th Streets, a jaywalker staggers into the street. This time, none of the passengers are harmed by the turbulence caused when the R instantly sways to miss him.

At 8th, enough people disembark and at about 9:45 AM, the R finally has empty seats. This good news is probably an indication of the bad news that ever since the pandemic, there are not enough people going to a sleepy downtown that has little or no work for them.

At every stop, most of the passengers have got on without paying, a trend that also began with the pandemic and now includes all demographics. The issue of non-payments now on BART as well as Muni, threatens both transit systems. It also raises the question: Should transit be free? Before the pandemic, those who took free rides were usually young males. Now when a woman in her late 50s who may have put thousands of dollars in Muni fare boxes since her childhood gets on, should we be really surprised, if after a hard day’s work, she also helps herself to a free ride? Especially if she must stand next to a teenager who has a seat?

Muni itself has contributed to the confusion. I have seen fare inspectors confronting riders who are standing while ignoring passengers passed out in their seats. Even Muni’s website is unintentionally ambiguous about the issue. The site’s page reads: www.sfmta.com/getting-around/muni-fares. Is that “getting around” the City by paying “Muni fares?” Or “getting around Muni fares?”

At 7th, SOMA is influenced by both Civic Center and the Tenderloin. The R passes the U.S. Court of Appeals Building. Constructed in a Beaux Arts architectural style, the building was completed in 1905, a few months before the 1906 Earthquake and Fire that leveled so much of San Francisco. Nevertheless, the building survived the disaster with some damage. In 1989, it was damaged in the earthquake but again repaired and remains in use. On this day, several men who appear to be homeless lay on the courthouse steps.

At 5th, the “Union Squarea” extends to Mission Street. There are shops, restaurants and the upscale Westfield Mall is one block away on Market. Some shoppers and tourists—perhaps lost or curiously wandering—walk between Mission and Market. The Old Mint—also a survivor of the 1906 and 1989 earthquakes—occupies the southwest corner of 5th and Mission. On the southeast corner stands the Chronicle Building. Founded in 1865, it was and is Northern California’s largest daily newspaper. But the paper’s physical size and influence have been reduced by the decline of print journalism in this post-literate century.

At 4th Street, the R passes crowds bustling around Yerba Buena, a “new neighborhood” according to Wikipedia. This is incorrect. As San Francisco author Rebecca Solnit explained in Hollow City, her 2002 book describing San Francisco’s economic progress and social decline, this new “neighborhood” has replaced the old, actual neighborhood that stood here. The neighborhood that stood here was impoverished but it was home to its residents, a multi-ethnic group of mostly single, older men. Like other neighborhoods in the City and the nation, it was targeted for an “urban renewal” program. Where a residential neighborhood once stood is now occupied by an upscale shopping center/movie complex Yerba Buena Gardens (YBG) and the Moscone Center convention site, what Solnit describes as an “obsequious monument to global capitalism.” Outside the Yerba Buena’s entrance, a group of carpenters protest the site’s working conditions.

Also occupying this land where poor people of different races were evicted from their homes stands a memorial sculpture dedicated to Martin Luther King.

Across the street from YBG, at mid-block between 4th and 3rd stands St. Patrick’s Church, the only vestige of the neighborhood “renewed” by Redevelopment. Originally this Roman Catholic parish was, like so many in San Francisco, home to Irish immigrants. Today it is a stronghold of SOMA’s Filipino American community. Like the Latinos in the Mission, Filipinos in the SOMA are pressured by gentrification. And like the Latinos, they are resisting.

After 2nd, Mission Street begins to take on the characteristics of the nearby Financial District. Three high rise skyscrapers soaring over 400 feet rise between 2nd and 1st. But at the corner of 1st, these structures are dwarfed by the Salesforce Tower, headquarters of the multinational software corporation. Completed in 2018, the Tower soars 1,070 feet high and is San Francisco’s tallest building. Visible from most of the City as well as Sausalito, Daly City and the East Bay hills, the Tower dominates the skyline just as Salesforce and other Big Tech corporations dominate the world economy and much of our society.

Today in light of the pathologies wrought by “social” media, Artificial “Intelligence,” crypto “currency,” the exploitation of workers by the gig economy, and other maladies caused or abetted by Big Tech, the Tower stands as a symbol of disruption as well as domination.

At the corner of Mission and Fremont, next door to the Salesforce Tower, stands—kinda, sorta—another symbolic skyscraper. At 645 feet high, the Millennium Tower is the City’s tallest residential building. Although 425 feet shorter than its next door neighbor, the soaring condominium is just as symbolic. Where the front door of 301 Mission once stood is now a construction site that has removed the sidewalk and narrowed Mission’s four lanes into three. In 2016, seven years after the Millennium’s completion and after it had garnered 10 architectural and engineering awards, it was discovered that the residential skyscraper is sinking and tilting, now as much as 29 inches. San Francisco’s “pay to play” governance, illustrated at 1660 Mission by the building scandals, is symbolized at 301 Mission by a crooked skyscraper. Reinforcing that symbolism is the fact that a resident of the Millennium is a well-known San Francisco politician.(2)

At Main Street, the 14R makes its only turn off Mission and moves toward Market. Midway there, by the delivery entrance of the San Francisco branch of the Federal Reserve Bank, it makes one of its last stops. In the previous century, before fear of terrorism changed so much of our lives, bicycle messengers and other delivery workers would ride into the entrance of “the Fed” and receive packages of newly printed currency to distribute to the banks that were our clients.

By now, there are only three other passengers, all men speaking in Spanish.

At Steuart and Mission, the 14R makes the final stop of its inbound route just one block from the location where in 1934, two unarmed labor union activists were killed. Their slayings set off the City’s General Strike that transformed San Francisco into a progressive and pro-labor town throughout the 20th Century. Here the operator takes his break. I thank him, get off, remove my bike from the rack and check its mechanical condition. As after many bumpy rides on City streets even while my bike is on a bus rack, the front brake has been knocked out of position. I readjust it, hop on my bike and start riding.

1. Buses were sometimes bombed by terrorists but that was a consequence of Pakistan’s volatile political situation, not the bus system or the conduct of its operators or regular passengers.

2. In keeping with anti-doxxing principles, the politician will not be named.