Representative Body of the San Francisco Bay Area People’s Food System Begins Meeting in 1976

Historical Essay

by John Curl, Part Eight of an excerpt from a longer essay “Food for People, Not for Profit: The Attack on the Bay Area People’s Food System and the Minneapolis Co-op War: Crisis in the Food Revolution of the 1970s”

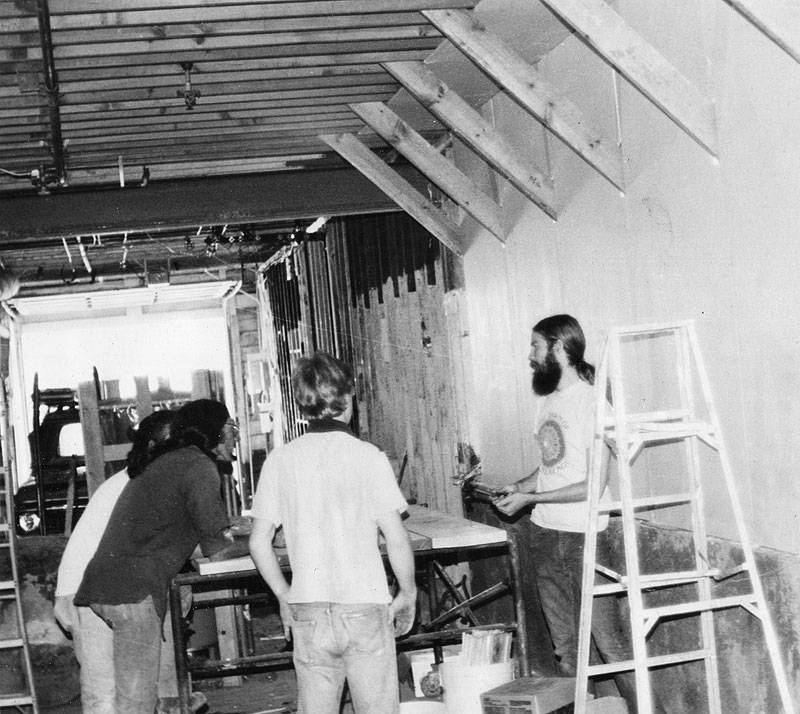

The collective at the Inner Sunset Community Food Store working on their new store over on Irving Street after they were forced to move back in 1982. That's an interesting story where the greedy property owner thought they could duplicate what the collective was doing and put up a mirror version of what we did after they forced us out. It of course failed as our customers all moved to the new place a couple blocks away. I was opposed to the plan to move to Irving and wanted to move into the Haight but Phil Bewely and the other guy who both eventually moved over to Rainbow grocery were dead set on a conservative agenda along the lines of packaging which got me booted out of the collective for my bulk agenda. This image is of me with Charlie Englestein (3rd from right with the glasses) who is bending over talking about the next steps in converting the former plumbing shop... Charlie was of course the main guy coordinating the project. I was the sheet rock guy as I was also doing produce shifts at the store... I'm the tall skinny guy on the right with the beard and long hair.

Photo and caption: Roger Herriod

Meanwhile, back in the Bay Area, the new Representative Body (RB) of the San Francisco Bay Area People’s Food System was meeting in April 1976. Their first order of business was representation. Twenty-one groups attended their first meeting, but eleven were objected to by other groups, mostly on the grounds that they were not yet producing any products, or were less than three people, or were uncertain of the definition of “collective.” There were also differences among RB reps over the timeline of developing a more unified system, some wanting to plow quickly ahead, while others wanting the organization to develop at a slower, more organic rate. They discussed the “initial basis of unity” and found significant differences among the collectives over how important the building of “a mass base for socialism” was to the goals of the Food System.(83)

At their second meeting, twenty-three groups were in attendance. By majority rule, with each collective having one vote, they accepted all the groups present into the decision-making body of the Food System. They then defined collective as “a group struggling to become non-sexist, non-racist, and remain anti-capitalist. Each individual must make a collectively agreed upon minimum time commitment. There should be non-hierarchical sharing of responsibility and initiative within the collective. Each member is accountable to the collective as a whole.”(84) They added that the means of production should be owned by the workers, and those that were not, should be changed as soon as possible; if the business were to dissolve, the assets would go to the community. Another issue raised at the second meeting was whether groups present were balanced in terms of Third World persons, and what was being done to serve Third World residents of our communities.(85) The discussion was expanded to include male-female, straight-gay, and age balances. Finally, the Food System meeting discussed developing an orientation process for new groups, including help in how to run a small business, and the history and politics of PFS.

At their third meeting, twenty-three groups were again present and fourteen made presentations. Decision-making was again discussed, and majority rule was accepted “as a temporary measure.”(86) Discussion included the idea that majority rule must have some reflection of minority opinion; that procedures should reflect the seriousness of the subject to be decided; and that criticism of decisions could be incorporated into the method for the next decision.

They discussed the issue of diversity in the Food System. Volunteers working in the stores were primarily white, young, and members of the counterculture. Until Ma Revolution in late 1975 decided to change their racial makeup through affirmative action, there were few people of color in the System. Some made the argument that the refusal to stock many foods that were familiar to the neighborhood, the priority of natural and organic foods, which were often more expensive, the reliance on voluntary labor, and the tendency of many stores to arguably be crowded, funky and inefficiently run, tended to isolate them from the Latino and Black communities in which they were often located. Many collectives replied they had made efforts to include Third World people and older people, and to serve a wider community, but few groups had made it a long-term high priority item. Most collectives said they had considered issues of sexism, but that the topic had not been thoroughly discussed. Most groups felt that low wages (under $200 a month) were one reason it was difficult to recruit Third World people to join.(87) The meeting decided to try to come up with a strategy for increasing the participation of Third World, gay, and older people. They also discussed the problems that parents encounter in trying to be active in the System and agreed to try to find solutions. The meeting ended with projections that the next meeting would try to produce concrete plans for further racially and ethnically integrating the Food System.

To help facilitate the process, Turnover printed Ma Revolution’s hiring questionnaire, which had been prepared by that store’s Third World Caucus. The introduction stated that the “present hiring committee at Ma’s is made up of all non-white people, and only nonwhite people are being considered for all presently available job openings.” The questionnaire began, “These statements are being considered in an evaluation of a basis to struggle. A challenge that is necessary to initiate a search into what is real and valuable for sound political development.” There would be a one-month trial period, and a six-month “commitment to struggling and working with each other.” Included were questions such as:

Job Background: What are your feelings toward collectives and collective work? Experience with collectives, if any. Define what collective means to you. Class Background: Include background and politics of parents. Describe politically why or why you don’t support their attitudes. Have you had or do you now have any affiliations with any groups that are pro or con capitalism? As stated in the principles of unity, our struggle will be purging ourselves of these three forms of oppression. What is your position on racism, sexism and elitism? What is your politics of food? How do you view agribusiness in California, the U.S., the World?(88)

As a result of this discussion, several of the collectives, including the Warehouse and the Haight Store, implemented preferential hiring plans to try to change the class, racial, and heterosexual makeup of their collectives.

A new collective store, Food For People, opened briefly near the Golden Gate Park Panhandle, but soon closed. In June, Good Life Grocery was taken over by the Peace and Freedom Party and dropped out of the Food System.(89) Later that year, Mechanics United, a much-needed support collective, housed at 209 Prospect Street, joined the System.

In May, 1976, PFS played host to the next West Coast Co-op conference, billed as “The Food System’s Position in the Class Struggle.” SFCW was the host and Red Star facilitated the Planning Committee. The only report on the conference published in Turnover was that a program for agricultural workers was approved:

We call on all class conscious co-op food workers to join with us in supporting a four point program to correct our neglect of the agricultural workers, with and without documents, who produce most of the food grown in California, where out of a 1973 average farm employment of 280,000, only 65,000 were family workers, while 215,000 were hired workers.

- POINT l. To coordinate with the UFW to supply people from the food system to help in boycott and picket lines.

- POINT 2. To offer the food system information network, both local and national, to the UFW; to help inform consumers on agricultural workers’ plans and problems.

- POINT 3. To educate/agitate among food system workers on the problems of agricultural labor under a capitalist system.

- POINT 4. To offer our food distribution resources to the UFW and help organize agricultural workers’ food buying clubs, to help alleviate their high cost of living.(90)

On May 23, the RB met all day and discussed “racism and its effects in our work and with the communities where our businesses are located.”(91) The RB formed three key committees: basis of unity and criteria for inclusion; decision making; and economic centralization. These reported back at the July 15th meeting.

Basis of Unity Committee: The Basis of Unity Committee distributed a second working copy of the proposed Basis of Unity. Members of the committee are now scheduling meetings with all collectives to hear comments and criticisms. The Basis of Unity will provide the context in which future Food System decisions will be made. Economic Centralism Committee: The Committee on Economic Centralism proposed that .2% [sic] of the gross income of collectives be paid into a central fund to be administered by a committee for purposes to be decided by the entire Food System. This proposal is pending a clearer idea of what our spending priorities will be.(92)

That same Representative Body (RB) meeting also accepted by a majority vote a proposal from the Decision-making Committee, with the proviso that it would be re-evaluated in January, 1977. Each collective had two representatives. Collectives with ten or fewer members had one vote and those with more than ten had two votes. For representation purposes, one member equaled fifteen worker-hours per week, whether done by one or several persons. Collectives with two votes were not allowed to split their votes except in case of emergency or on-the-spot decisions. RB representatives could decide issues directly affecting the entire Food System, conflicts within and between collectives (if they could not be settled by other means), questions of political alliances into which the entire Food System might enter, and the operation of a Food System central fund. Decisions affecting the workplace and single-collective political alliances would continue to take place in the collectives themselves.

Any proposal brought to the RB would be preliminarily discussed and a vote taken whether to consider it. A considered proposal would be sent back to the collectives for discussion, then voted on at the next RB meeting. Decisions would be by majority rule, subject to a three-week period of re-evaluation and criticism, after which all decisions were final: “However, we need to be realistic about both the Food System and the RB. The Food System is not a unified political organization but a mass organization with many varieties of political and personal opinions and experience. Given our differences, it would be destructive rather than progressive to expect that all of us will act together on every issue. Therefore we establish a procedure for principled non-compliance with a decision.”(93) They established an “evaluation committee” to investigate those cases and bring their evaluations to the RB.

By the end of 1976 the Representative Body had formulated a Basis of Unity that had been approved by most of the collectives and by the RB as a whole. Committees formed to provide improved childcare, to increase economic centralization so that resources could be shared and wage levels equalized, to develop a system-wide hiring policy, to develop a program of political study, and to unite food activists with progressive community groups through a solidarity program. They established a central fund, to be supported by donations from all collectives, based on income, to fund projects approved by the Food System. Loans were made to Uprisings and to Ma Revolution. For the first time the workers at Seeds of Life and Community Corners received anything approaching a living wage.

But it was too late for Seeds, which had become isolated from the wider Mission community. Faced with severe economic and organizational problems, Seeds closed the storefront and merged into the Latino St. Peter’s Church buying club, that originally had helped them get started.(94)

In January, 1977 the RB decided to elect a steering committee to facilitate the work. Although various people were uneasy with some of the candidates, or actually opposed them, the desire for unity trumped all misgivings, and the selection process resulted in all nominated candidates being elected unanimously.(95)

While many in the Food System applauded these developments as progress, others found them increasingly disturbing. Charlie from Inner Sunset Co-op later expressed the sentiments of many: “I think that in the development of the RB and further in the creation of the steering committee, we didn’t really see a representation of the people who were in the collectives. Within each of those collectives I think there were people who ranged from being not interested in politics at all to not being interested in that kind of centralized form of politics. So what happened was the people who did have an interest in a more centralized form of politics and in using the Food System in that way tended to go to RB meetings and ultimately many of those people ended up on the steering committee, where even more power was concentrated. The steering committee was originally intended to facilitate RB meetings, prepare agendas, make things go more smoothly at meetings. But in fact, they had all the power at the meetings and they controlled the meetings and they also then controlled the whole Food System insofar as what these meetings dealt with.”(96)

The steering committee then unilaterally rewrote the Basis of Unity, de-emphasizing the politics of food and making democratic centralism into the organizational structure of the System.(97) They sent representatives to all the collectives to try to gain support for the new document. Many collective workers objected strongly to the rewriting of the document previously agreed upon. Charlie from Inner Sunset continued: “They came to our store and talked to us about the new Basis of Unity, which they had rewritten, asked us for financial statements and all this other stuff. We just totally trashed the person that they sent. That was what stimulated us to withdraw immediately after that. [T]he thing that ultimately destroyed the Food System was the movement toward centralization of power which ultimately set up a situation where either police agents could come in and provoke and disrupt and destroy, or for a few individuals to take power, and in that way no longer represent the Food System anyway. So either way we lose.”(98)

At that point, Rainbow Grocery withdrew from the Food System, and chose to go it alone. Other Avenues also stopped going to meetings.

An All-Worker Conference was scheduled for April 17, 1977. The agenda included a discussion of the new Basis of Unity, and criticism and self-criticism of the steering committee. It was going to be a pivotal conference.

Notes

83. “The Food System Meets,” Turnover 12 (May-June, 1976): 3-5.

84. Ibid., 5-6.

85. The term “Third World” was often used in America at that time to loosely mean anyone not entirely of European descent. It comes from the Maoist theory of the “three worlds.” Many Americans assumed that the first two “worlds” were the Capitalist World and the Socialist World, lumping China and the USSR together. However, the First World actually consisted of the two cold war superpowers, the U.S. and the USSR; the Second World were the industrialized nations of Europe and Japan; and the Third World were the “developing” nations, or everybody else. According to this Maoist analysis, China was the natural leader of the Third World. Ironically, Many indigenous people considered themselves a Fourth World.

86. Turnover12: 6.

87. Older, “People’s Food System,” 41.

88. “Ma’s Questionnaire,” Turnover 12, May-June, 1976, 7-8.

89. Turnover 13, July-August 1976, 24.

90. Turnover 16, November 1976, 23.

91. Turnover 13, July-August, 1976, 21.

92. Turnover 14, September, 1976, 8.

93. Ibid., 7-8.

94. Older, “People’s Food System,” 41.

95. Ibid., 41.

96. Charlie, “Another View of the Food System,” 50.

97. Older, “Peoples Food System,” 42.

98. Charlie, “Another View,” 50-51.