Hal Call, Pan-Graphic Press, and the Adonis Bookstore: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Protected "Hal Call, Pan-Graphic Press, and the Adonis Bookstore" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 17:14, 7 July 2017

Historical Essay

by Joe Bourdage

Portrait of Hal Call, 1953.

Courtesy of Harold L. Call papers, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries.

| When the Adonis Bookstore opened at 350 Ellis St. in March 1967, the surrounding Tenderloin neighborhood became home to the first gay bookstore in the United States. The store’s principal owner, Hal Call (1917-2000), was a gay rights activist, WWII veteran, and a key member of the Mattachine Society, the country’s first “homophile” organization. From the mid-1950s to the late-1960s, Call leveraged his influence in the Society to establish his own private business enterprises, which began with Pan-Graphic Press, a gay printing press, and eventually widened to include the Adonis Bookstore and the growing market for gay literature and erotica. Call’s timely shift from public organizing to private business coincided with ongoing generational and institutional shifts in the broader gay rights movement, suggesting that his transition away from public life constituted a shrewd and motivated exit. |

When Hal Call opened the Adonis Bookstore in the heart of San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood in March 1967, the Ellis St. storefront became the country’s first gay bookstore. For Call, a key leader of the Mattachine Society the nation’s first sustained gay rights (“homophile”) organization, the new venture into the production and sale of gay erotica marked a personal withdrawal into private business after nearly fifteen years of public organizing. Call’s influence within the Society provided him ample opportunity to establish ventures in pursuit of the Society’s goals, and when the Mattachine’s influence waned in the 1960s, Call transitioned smoothly into operation and expansion of these private businesses, which he ran in the Tenderloin neighborhood until his death in 2000 at the age of 83.

Coming to San Francisco and the Mattachine Society

Throughout his life, Call maintained an assimilationist ideology toward homosexuality that informed many of his public and private decisions: he believed that gay men were fundamentally the same as everyone else, “with a different object, perhaps, for [their] sexual gratification” (Call 10). His political goal, and the goal of the Mattachine Society under his influence, was to accommodate gay people politely into American society, without the riots and political demands for equality that would define the later movement.

This was the genteel ideology that Hal Call brought with him to San Francisco in the fall of 1952. When he arrived in the city, Call was a thirty-five-year-old journalist and a veteran army officer who had grown up in small-town northern Missouri. In August of that year, while living in and enjoying the seedy gay nightlife of post-war Chicago, Call was arrested for “lewd conduct” and was forced to pay an $800 bribe to evade the charges (Sears, “Hal Call” 154). In a moment that proved transformative for Call, he was asked to resign from his job at the Kansas City Star after word of the arrest spread,and upon packing up and heading home Call decided that he “was going to move somewhere I wanted to live and create my own economic support and live as I wanted!” (Sears, Behind 141). He and his lover Jack packed their car and fled to the West.

In San Francisco, Call quickly became involved with the Mattachine Society. In 1953, the organization relocated its headquarters from Los Angeles to San Francisco, and amid the anti-Communist mania of McCarthyism, its original leadership resigned. Into the void of leadership stepped Call, who effectively cordoned off the leftist fringes of the Society and reframed its mission around the assimilationist ideology that he and other more conservative members favored. Critically, the organization adopted non-confrontation with law enforcement as an official policy, and granted Call, ever the businessman, the authority to look into “establishing the Society’s own magazine” (268).

Pan-Graphic Press

Because of the growth and shake-ups within the Society, Call felt that his influence could prove tenuous. In November 1954, he leveraged his experience in journalism and advertising to start Pan-Graphic Press, with the idea that this venture would publish a magazine to serve as a mouthpiece for the Mattachine. As Don Lucas, the co-owner of the press, observed: “Hal wanted more than anything else to produce a magazine to be in competition with ONE”—a competing gay rights magazine based in Los Angeles that was promoting a more radical, separatist ideology (301). Lucas recognized that “by getting Pan-Graphic to do all this, then [Call] could produce what he wanted” (301).

Call deliberately established Pan-Graphic as an entity outside of the Society. As early as 1954, Call was growing displeased with the direction of the organization, and feared the voting power of its new members. If Call were to be able to fine-tune the message of the Mattachine, which lacked a broader message as a result of squabbles between its various city chapters,he recognized that “we had to have our own printing department” (Call 38). After the establishment of Pan-Graphic, which operated out of the Williams Building at 693 Mission St., Call left his job to become self-employed at the press, where he paid himself a comfortable salary (39).

For Call, the publication of a Mattachine Society magazine was to serve two audiences: both “the general public, educating Mom and Dad about the realities of homosexuality,” and “the homosexual, helping him raise his self-esteem and to fit in” (Sears, Behind 297). Under Call’s direction, the new magazine, the Mattachine Review, retained its publisher’s ideology. In trying to connect issues of homosexuality to broader audiences, the magazine discouraged gay men from “[trying] to establish his own subculture” (297).This message fed into the Mattachine’s image of being too staunchly assimilationist and unwilling to confront society at large, a criticism against the Society that lingers into the present day. The magazine lost readership throughout the 1960s. Don Lucas, for his part, could never “summon the courage to publicly confront Call when Mattachine interests diverged with Hal’s self-interest,” and some scholars credit Call’s dual involvement with the Society and Pan-Graphic as the cause of the Mattachine’s ultimate undoing (301).

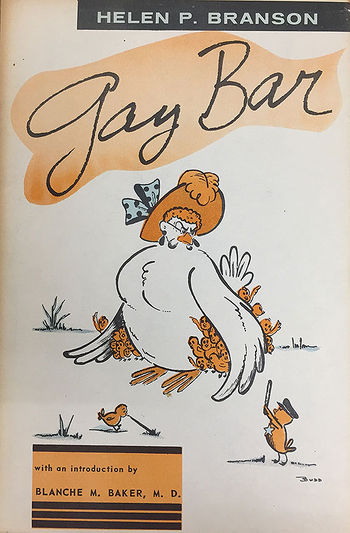

Cover of "The Gay Bar," from the Donald S. Lucas Papers, courtesy of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society.

Despite the slow unraveling of the Mattachine, the new venture succeeded in slowly shifting Call’s attention away from direct homophile organizing. In the early years of Pan-Graphic, Call ventured outward from the Society into broader gay publishing. In 1956, Pan-Graphic printed the lesbian magazine The Ladder during most of its inaugural year, and in 1957, it published its first of many full-length gay novels, The Gay Bar. In short order, Pan-Graphic became the premier gay publishing service of its time, “publishing booklets on transvestism, West Coast Bars, and the sexual continuum” (Sears, “Hal Call” 156).

Pan Graphic’s largest subsidiary later became the foundation for the Adonis Bookstore. In 1958, Call and Lucas established the Dorian Book Service, a “gay and lesbian literature clearinghouse” (155). From their office in South of Market, Call and Lucas printed and sold books by mail to people in towns “lacking progressive bookstores” (155). Catalogs of books published by Pan-Graphic Press and for sale through Dorian Book Service were advertised in detail in the Dorian Booklist, a short circular that included order forms, and in the Dorian Book Quarterly, a $2/year subscription magazine complete with images and reviews of current offerings. The first issue of the Quarterly, from January 1960, lays out its purpose:

Fifteen million adults in the U.S. today are predominantly homosexual, according to sexological research experts. Here is one of the nation’s largest “minority groups” not yet widely served with books explaining their situation and providing answers to the dilemma in which most of these people find themselves…Dorian Book Quarterly is a new and unique venture which will attempt to make known to an ever-expanding readership the availability of most of the books on sex variation and related themes.

With the success of Dorian in San Francisco and beyond, Call’s efforts began to turn away from the organized homophile movement and toward his private enterprises. Between 1964 and 1967, Pan-Graphic published only ten issues of the Review before publication ceased altogether (Sears, Behind 520). Especially after the Stonewall riots in 1969, a new generation of gay rights activists had assumed the mantle from Call and others, and the prominence of the Mattachine Society, at least partially as a result of Call’s actions, had waned.

Adonis Bookstore

Call completed his turn from the early homophile movement to entrepreneurship in gay erotica early in 1967. In March, he and three others—Bob Damron, Robert Trollop, and Jack Tennyson—opened the doors to the Adonis Bookstore at 350 Ellis St., between Jones and Taylor. Though Damron and Trollop dropped out of the venture in 1969, Call continued to own, operate, and expand his business on this block until his death in 2000.

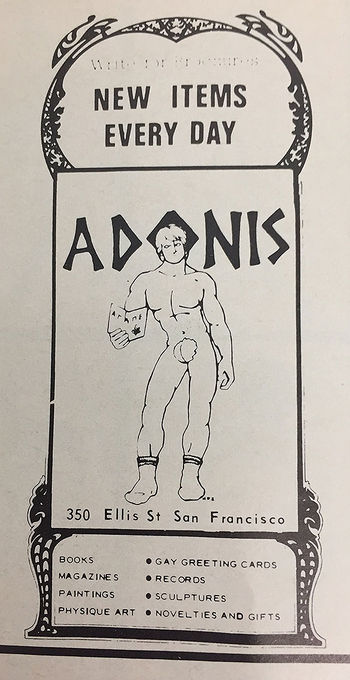

Golden Boys, courtesy of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society

Call would later describe the period of the late 1960s and early 1970s as “the golden era of gay sexuality” (Sears, “Hal Call” 158). Inside the store, Call sold pulp paperbacks published by Pan-Graphic in addition to full-color male-physique magazines like Damron and Trollop’s Golden Boys. The Adonis Bookstore logo can be found among the advertisements in the back of the first four issues of Golden Boys, all published in 1967, when Damron and Trollop were still stakeholders in the store. Above and below a sketch outline of a masculine figure holding a pamphlet and wearing nothing but socks and a fig leaf, the simple ad indicates that Adonis stocks “New items every day” and sells “books, magazines, paintings, physique art, gay greeting cards, records, sculptures, and novelties and gifts.”

The business of gay erotica proved to be the right fit for Call’s personal politics and his unabashed interest in gay sexuality. After Adonis opened, he recalled, “my emphasis and energy was centered there. We were having hundreds of customers a day!” (Sears, Behind 291). With this energy toward his own efforts in San Francisco came an understanding that a new generation of gay activists were rising with a distinctly liberationist ideology, which Call called “sexual freedom.” As Call told JT Sears toward the end of his life:

I kind of dropped out of the loop [in 1967] … Other organizations started coming into being and the idea of sexual freedom started taking hold among younger people, particularly on college campuses. By the late 1960s, there were gay activists and sexual freedom groups popping up. (293)

As Ted McIlvenna, a contemporary of Call, noted, “[Call] moved aside at a time when he should have moved aside. Now, that is hard to do!” (293)

Though perhaps not so for Call. With business running smoothly at the bookstore, Call’s personal and business interests evolved into both production and distribution of sale items at Adonis. In the years before his gay patrons relocated en masse from the Tenderloin to the Castro, Call’s neighborhood storefront served as a “recruiting ground for male models as well as Mattachine activists” (Sears, “Hal Call” 158). Within a year of the store’s opening, Call had launched his own production company, Grand Prix Photo Arts, and had begun collaborating with well-known erotic photographers and adult filmmakers. As Call put it himself: “I preferred Adonis to the old maid of the Mattachine.” (Sears, Behind 290)

The turn of the 1970s proved to be the right time for Call to operate his businesses. After police raided the bookstore in August 1970 and seized many of Call’s in-house films, a judge dismissed the charges and Call’s business continued (276). Though Call complained that “this was the cops still trying to make pictorial illustrations of people [having sex] a chargeable offense,” he must have recognized that the city’s treatment of gay-owned businesses had changed drastically since his arrival in the city, an evolution that was “attributable, in part, to [his] longtime efforts” (277). By his very own earlier activism, Call was able to ward off the legal and thus implicitly-moral challenges to his livelihood.

In the years following the raid, Call continue to expand his businesses on the Ellis St. block. In 1973, he opened a theater on the block, which he dubbed CineMattachine, with the money acquired from the buyout of Damron and Trollop’s stake in Adonis. Though the Tenderloin declined as a center of gay life in San Francisco in 1970s, Call remained in the area for the rest of his life, working out of a small office above his theater and continuing to create erotic films, some of which have since become collector’s items (Szymanski). By the time the last of Call’s businesses closed, in 2005, there were “roughly 7,000 movie titles still stacked” in Call’s office—hundreds of which he had made himself (Szymanski).

Call’s personal business successes through Pan-Graphic Press and the Adonis Bookstore were ultimately the opportune products of his influence in the Mattachine Society. Though Call’s reputation in the history of the gay rights movement is mixed—there are some who applaud him and others who denigrate him for his political conservatism and his keen understanding of “the business of activism”—he is nonetheless a key figure of the post-war generation of gay organizing (Sears, Behind 15). His business legacy, which outfitted much of the 300 block of Ellis St. in the heart of the Tenderloin for nearly forty years, has outlived the changes to that neighborhood and still serves as an exemplar of the evolution of gay life in 1960s San Francisco out of an underground network of bars and clubs and into the normal business hours of the day.

Works Cited

Call, Hal. "VOICES of the Oral History Project." Interview by Dennis Saxman. GLBT Historical Society, n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2017.

Dorian Book Quarterly Jan 1960: 2-3. Print.

Golden Boys #1 1967: Print.

Sears, James T. Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation. 2006. Print.

Sears, James T. "Hall Call (1917-2000): Mr. Mattachine." Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context. Ed. Vern L. Bullough. New York: Harrington Park, 2003. 151-59. Print.

Szymanski, Zak. "Historic Circle J Club Closing." Bay Area Reporter. BAR, Inc., 24 Nov. 2005. Web.