Fillmore Bill: Bill Graham’s Legacy

Historical Essay

by Kaan Ertas, 2021

| Bill Graham is the rock impresario behind The Fillmore, the Day on the Green concerts and the overall popularization of rock music in the late 60s and 70s in San Francisco and across the country. Graham’s legacy lives on both in rock circles and in the fabric of San Francisco, perhaps best exemplified by the naming of the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium after his passing away in 1991. While the auditorium’s website simply states that he “began the rock ‘n roll movement in San Francisco in the 1960s” (Bill Graham Civic Auditorium), his impact on the music scene was much more nuanced. His business acumen and the way he ran his business often ran counter to the values held by artists in the counterculture movements of the time—the same artists that gave him the opportunity to rise to fame. |

Bill Graham’s rise to fame coincided with (and is partly owed to) the heyday of late 60s counterculture movement and its music scene in San Francisco. Greg Gaar, a native San Franciscan photojournalist, describes the Haight-Ashbury of 1967 as an environment where musicians were free of pretension and concerns of commercial success. In large contrast to the famous artists of today, artists back then lived with (and lived just like) the people they performed for. In Gaar’s words, “The Grateful Dead would be sitting on the front steps of 710 Ashbury, where they lived. On hot days, they would be squirting cars with a water hose as the car went by …. You’d see Janis Joplin shopping on Haight Street.” (1)

The ideology of the hippie counterculture was also largely present in the music performance scene. In his essay When Music Mattered, Mat Callahan talks about how many concerts of the time were open to the public, free of charge and performed in open air on the streets.(2) The concerts weren’t all about music; they provided a social platform for like-minded individuals. The Grateful Dead, who appeared quite frequently under Graham over the years, were known for making music that was hard to commercialize. (3) Even the recordings of the band had a grassroots, anti-capitalist feeling to them; they set up a ‘tapers section’ at their concerts so people would be able to directly record them. Callahan describes the importance of music to the hippie counterculture:

“Music mattered because it consciously and directly challenged the state. It did this by granting permission to do things the state prohibited or restricted. Dancing, drug taking, and sexual adventure were all encouraged by music in defiance of laws regulating such activities.” (4)

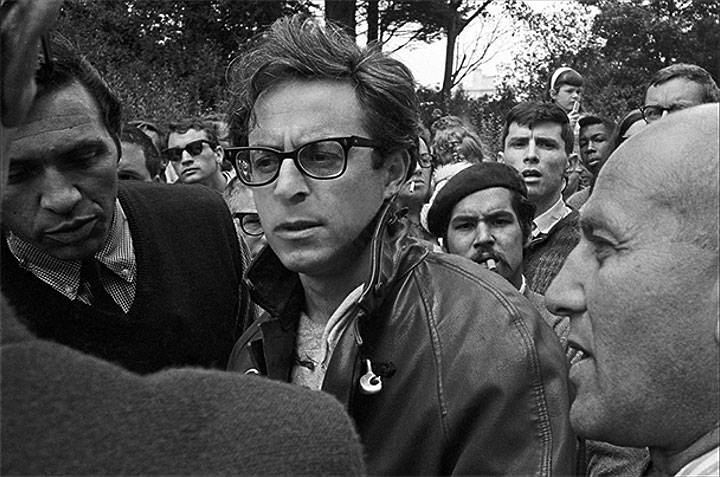

During the 1965 Mime Troupe arrest: from left to right: Bill Graham, Ron Davis, Luis Valdez, Paul Jacobs.

Photo: © Erik Weber, used with permission

Another important part of the scene at the time was the activist theatre group called the San Francisco Mime Troupe. The group, famous for their commedia dell’arte performances, often performed in the parks of San Francisco with adapted plays addressing issues such as gender and sexuality. After their performances were accused of being in “poor taste” and against social values, the Recreation and Parks Commission of the city voted to revoke the group’s park performance permit. The milestone arrest of Ronald Davis, founder and leader of the Troupe, after he attempted to perform in protest of the decision, gave Bill Graham the opportunity to organize a benefit concert for the troupe to cover legal expenses, focused on the freedom of expression and assembly.(5)

The handbill for the first SF Mime Troupe benefit concert.

Image: Lemke and Kastor’s The Art of Fillmore: 1965–1971

The event happened on November 6, 1965 at the troupe’s studio at 924 Howard Street, with the participation of artists many artists, among whom were Jefferson Airplane. It was a huge success, raising approximately $2,000 in funding.(6) After this concert, Graham organized countless others, managed several concert venues, and had an extremely successful career as a businessman in the music industry. This included two additional benefit concerts for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, both of which were held at the Fillmore Auditorium. This venue became one of Graham’s most famous and successful venues during its active years from 1965 to 1968.(7)

It became clearer in the months following the first benefit concert, and quite obvious in the years to come, that Graham hardly shared the same ideology that his performers held. He did not keep it a secret that he was running a business more than making a countercultural statement. His interest in bringing good and new music to the masses for a fee conflicted with the anti-establishment ideology of the counterculture movement that gave him his first important gig. In fact, Graham and the Mime Troupe are known to have conflicted on this very matter between the first and second benefit concerts for the troupe. Peter Berg, actor and playwright for the Mime Troupe and co-founder of The Diggers, recalls:

“There was a crucial meeting between the first and second benefit. Where he suddenly said, ‘All the political pretensions that you’re involved with suck.’ He said ‘Look, you’re asking me as a business manager to provide you with nickels and dimes. And I can do thousands. There’s a funnel here. I saw it.’ And the second benefit was his. And he was into it. And that made him Fillmore Bill. He became Fillmore Bill at that benefit.” (8)

The “Fillmore Bill” persona is perhaps best depicted in Graham’s own words, from his interview with KPIX Eyewitness News from 1969:

“Other places have been run … by ‘love people’, ‘love children’, [who say] ‘we want to do our thing man.’ Well, if you refuse to accept the fact that you’re dealing in a society based on black and white, and green, and red, and dollars and cents, and time clocks … you’re going to get into trouble.” (9)

Graham wasn’t anti-establishment like the artists he managed; on the contrary, he had a symbiotic relationship with the powers that were. Graham said:

“You cannot do it with thoughts of excluding the straight man, the shirt and tie world; you can’t, because when you want to put an ad in the paper, you go to the straight man. When you want to get a permit, you go to the straight man.” (10)

Berg recalls Graham talking about certain attendees of the second Mime Troupe benefit concert, held at The Fillmore: “Don’t let him in, don’t let them in. They don’t have tickets? F*** him.” Ronnie Davis put it plainly: “What we never did was convince Bill Graham that art and social change were more important than money.” (11)

Bill Graham’s legacy is mostly regarded as him having played a pivotal role in the popularization of rock music. We partly owe to him the growth of the rock scene, but also its changing landscape and ideology. Rock music transitioned from streets into isolated venues, the admission costs of which became astronomical as the events grew larger. This limited people’s access to live music and turned concerts into a trade, a commodified experience, and a product of capitalism. This is not what the ‘60s counterculture ideologies stood for; to witness the change, we can take a look at the handbill for the first SF Mime Troupe Appeal Party, authored by Graham himself. In response to the revocation of the troupe’s performance permit it states:

“[t]he 20,000 persons who enjoyed the troupe’s free park performances in the past four years will no longer have that opportunity, thanks to the ‘good taste’ of six commissioners.”(12)

It is hard to say whether he anticipated playing a role similar to the commissioners himself, as he restricted access to rock music and paved the way to its commodification in isolated - and paid - venues. Nor can we know if the music scene would have transformed into the profit-seeking industry it now is without Bill Graham, but we can say that he catalyzed the process.

Notes:

1. Rommel, Diane. Rock Photographer Greg Gaar Reflects on the Many Lives of San Francisco. n.d.

2. Callahan, Mat. "When Music Mattered." Carlsson, Chris and LisaRuth Elliott. Ten Years That Shook the City, 2011.

3. Kot, Greg. The Grateful Dead: The band that could save music. n.d.

4. Callahan.

5. Barshak, Jackie. San Francisco Mime Troupe Arrested. n.d.

6. Ibid.

7. Fillmore, The. About. n.d.

8. Graham, Bill. Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock And Out. Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2004.

9. Graham, Bill. "Concert and Bill Graham interview at Fillmore West." KPIX Eyewitness News. Belva Davis. 1969.

10. Ibid.

11. Graham. Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock And Out.

12. Graham, Bill. SF Mime Troupe Appeal Party Handbill. San Francisco, 1965.

Other sources:

Bill Graham Civic Auditorium. About. n.d.

Lemke, Gayle and Jacaeber Kastor. The Art of Fillmore: 1966-1971. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005.