Curatorial Brilliance: Grace L. McCann Morley’s Directorship at the San Francisco Museum of Art

Historical Essay

by Justin Muchnik, 2019

| Grace L. McCann Morley, a Berkeley native, became the first director of the San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMA, now known as the SFMOMA) in 1934. She faced distinct disadvantages based on the museum’s young age and its geographical distance from art-world centers. Nevertheless, she tackled these challenges and made the SFMA a respected and popular museum by focusing on curatorial research, in the form of a world-class arts library, and public outreach, through community programs catered toward a broad audience. Ultimately, although she enjoyed great successes in her tenure at the SFMA, in 1958 she resigned as director under circumstances that are still ambiguous to this day. |

A portrait of Grace L. McCann Morley, c. 1945.

Photo: courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The year was 1940, and San Franciscans were protesting. A crowd of 1300 people had gathered at 10 PM on this warm Monday in July; it would not disperse. The persistent townspeople were sitting down on the floor, adamant in their refusal to evacuate the premises. Their reserves of patience seemingly infinite, they waited. These 1300 San Franciscans were far different from the protesters that have written themselves into the history books of the City by the Bay. They were not disgruntled longshoremen holding the line on the waterfront, nor were they young activists fighting to save the Fillmore. No, they had a very different goal in mind: whatever it took, they were going to see the show. This was, after all, their last chance.

The 1300 pro tem protesters were all sitting inside the San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMA, now known as the SFMOMA), dismayed at the fact that the galleries were closing for the night. In their gesture of defiance, they were demanding to get one last look at the landmark exhibition “Picasso: Forty Years of His Art” before it departed for good to continue its multi-city tour (Kirk 2017). The show was momentous—so momentous that even the art critic for the Los Angeles Times urged Southern Californians to travel up to San Francisco to see “the most brilliant colors ever painted, thrilling drawing, tender sentiment, brutal and cynical distortion or realism, gorgeous decoration” (Miller 1940, p. 8)—and it featured masterpieces from Picasso’s already-legendary oeuvre up to and including the world-famous Guernica. Nevertheless, it was an art exhibition all the same, and art exhibitions are not particularly known for generating enough public enthusiasm to make hundreds of people plead with a museum not to close its doors. So how, by the beginning of the 1940s, had San Francisco become a city of such uniquely passionate art-lovers?

The answer, in fact, seems to have less to do with Picasso and his brilliant colors, and more to do with a woman named Grace L. McCann Morley (1900–1985) and her brilliant ideas. As the first director of the SFMA, Morley overcame institutional and geographical disadvantages to build a museum at the forefront of collections research and community outreach, creating the type of institution that could not only exhibit Picasso’s landmark mid-career retrospective but also have a crowd of citizens begging to stay past closing to see it on its last night there.

Morley was a Bay Area native, born in Berkeley in 1900, and she graduated from UC Berkeley with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in French literature in 1923 (Straus 2010). Her studies took her next to the Sorbonne, where she was exposed to the modern art scene in Paris while she earned her doctorate in art history, but she soon returned to the United States and took on a curatorial position at the well-respected Cincinnati Art Museum in 1930 (Straus 2010). Her immediate success turned heads; in 1934 she accepted a new role as the first director of the soon-to-open SFMA (Strauss 2010).

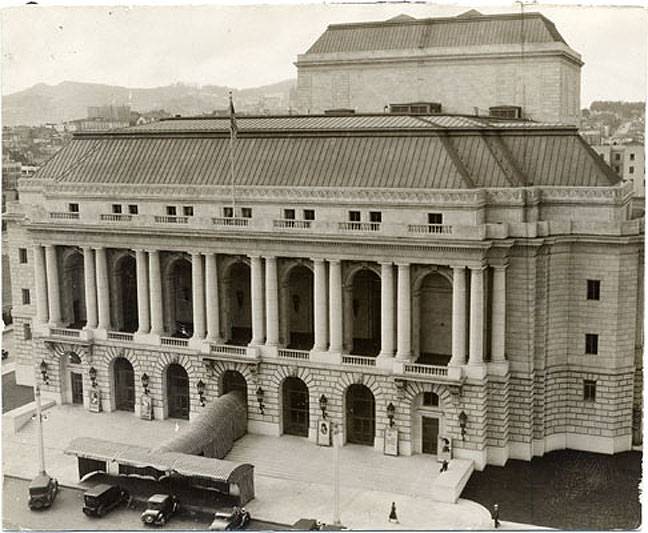

From the moment her museum first opened its doors in 1935, Morley contended with two disadvantages that many of her East Coast counterparts did not have to face. One, of course, was the young age of the SFMA. The venerable institutions of the Northeast had comparatively long histories; the Metropolitan Museum of Art for example, was founded in 1870 (“A Brief History of the Museum” 1999). In an institutional model where trust and status are gained over time, the SFMA’s newness could be seen as a true liability. Of course, youth alone did not preclude a museum from prestige. The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), which opened in 1929, was already making a name for itself under the stewardship of the upstart director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (“The Museum of Modern Art History” n.d.). But the MOMA, situated in the heart of Manhattan, had a geographical advantage that the SFMA lacked, for the other challenge that Morley experienced was the very fact that her museum was located in San Francisco.

The original location of the SFMA (War Memorial Building, Civic Center).

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, aad-7675

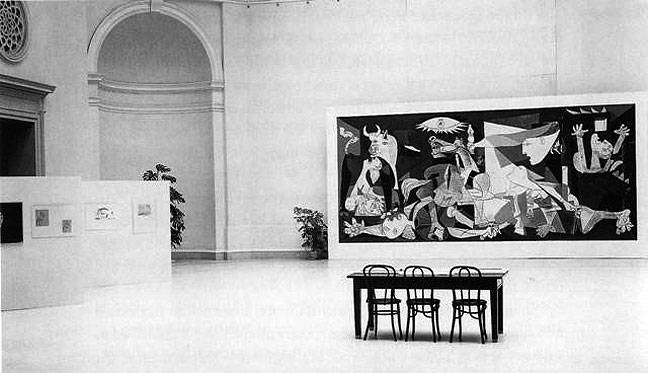

With Paris in the 1930s as the consensus art capital of the global West and with New York nipping at its heels, San Francisco was not much more than a far-flung parochial outpost in the art world. Scholar Kara Kirk writes that “Morley faced significant obstacles in bringing art to the West Coast,” because “in addition to the often prohibitive [sic] cost of shipping works thousands of miles and insuring them en route, she had to persuade lenders . . . that sending their artworks [to a minor arts town] was worth their while” (Kirk 2017). In fact, Morley herself acknowledged San Francisco’s low status in the art world in a 1939 letter to a New York-based administrator of the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign, the group that sponsored the first exhibition of Guernica at the SFMA (a year before it returned to the city with much fanfare in 1940). Responding to the administrator’s concern that the show was not garnering enough high-profile publicity, Morley explained that the arts scene “is not highly developed here in San Francisco,” especially compared to New York (Morley 1939, p. 1). Morley understood that for someone accustomed to New York-level arts infrastructure, the press accompanying a San Francisco exhibition could seem scant, and she owned up to the limitations of a museum trying to operate in what was then an art-world backwater.

Guernica on display at the SFMA in 1939 (it would return in 1940 for the Picasso retrospective).

Photo: courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Thus, lacking the prestigious history or optimal geography for her museum, Morley dared to innovate: she built a reputation for pushing the boundaries in both collections-based research and community-based outreach. Morley had a prescient understanding for the importance of research and libraries to the functioning of a museum. In an essay she wrote while at the Cincinnati Art Museum, she argued that “from the curator’s point of view the library is the very heart of the museum” and that “books stand next in importance to the art works themselves in the operation of any Art [sic] museum” (Morley, qtd in Benedetti 2003, p. 33). This sentiment was remarkably ahead of its time: echoes of Morley can be heard in art historian Iftikhar Dadi’s 2012 remark that “in order to contribute to cultural value, curating needs to be firmly conceived as research” (Dadi 2012). Upon arriving the SFMA, Morley immediately set to work creating one of the finest arts libraries on the West Coast. In a 1960 interview about her tenure at the SFMA, Morley explained that, beginning in 1935, she “tried to build [a library] systematically around our exhibitions and our growing collections, trying also to have all the indispensable publications on modern art, all the leading art periodicals” to create “an indispensable reference and research instrument for the museum’s staff members when organizing exhibitions or preparing educational programs” (Morley 1960, pp. 120–121). Through this library, Morley’s SFMA steadily gained credibility as a serious museum, one worthy of housing exhibitions of Picasso and the like.

In order to engage the San Francisco community, though, Morley had to pioneer novel methods of museum outreach, such as the “educational programs” alluded to in her interview. She established regular events for the general public, including “Painting for Pleasure” classes, which provided arts supplies and instruction to museumgoers (Kirk 2017), or “Art in Cinema,” the first film screening series at any American museum (Straus 2010). Interestingly, in the 1950s, Morley took these ideas a step further and began broadcasting a regular public-service television show called “Art in Your Life,” which reached over 40,000 San Franciscans with its accessible and exciting art-related content each week (Kirk 2017). Moreover, Morley insisted that the museum remain open late into the evenings, in order to make it accessible to swaths of the populace beyond what she termed “the leisured people” (Morley 1960, p. 61). For this reason, the SFMA operated on an unusual noon–10 PM schedule (Morley 1960, p. 62). Overall, by initiating these educational outreach programs and making her museum so friendly toward non-traditional audiences, Morley built a large and committed base of visitors. In a city with a population of only about 635,000, yearly attendance figures at the SFMA averaged around 130,000 by the early 1940s (Holz and Lemieux 2007, p. 6)—and, of course, 1300 particularly devoted patrons were even willing to sit down on the gallery floor because they wanted to look at Picassos past 10 PM.

But, in a mystifying postscript to this success story, it turns out that the museum that Morley made so beloved to so many San Franciscans may not have exactly loved her back. In 1958, after over two decades at the helm of the SFMA, Grace Morley stepped down under ambiguous circumstances. It by no means marked the end of her career—she would move to India to take up the inaugural directorship of the country’s new National Museum and, later, a high-ranking post on the International Council of Museums (Straus 2010)—but it was an unexpected and apparently unpleasant ending to her stellar tenure in San Francisco. In her 1960 interview, she gave no specific reasons for her resignation, stating only that she “had found conditions increasingly unfavorable” (Morley 1960, p. 224), but it may be telling that after she left San Francisco, she apparently never once returned in her lifetime (Straus 2010).

A number of scholars, including archival researcher Megan Martenyi, believe that Morley may have been a lesbian, though because she was notoriously quiet about her private life there is no way to know for sure (Martenyi 2017). Martenyi notes the coincidence that Morley lived on the outskirts of the North Beach neighborhood, known as one of the primary “cultural spaces being cultivated by queer women in San Francisco,” and she left the city around the time that “the pressures on lesbian social life escalated” with increased surveillance, police raids, and other enforcement measures (Martenyi 2017). Of course, it is impossible to move beyond mere idle speculation, but it is clear from her own testimony that Morley and the SFMA did not part on the best of terms.

And for those 1300 museumgoers who sat down in the galleries on a Monday night in July 1940, that alone might have been something worth protesting. Likewise, for those of us today who enjoy popping into the SFMOMA to admire an Agnes Martin or a Mark Rothko, perhaps we should spare a thought for the woman who put the museum on the map.

Further reading:

Morley, Grace McCann L. (1982). Interview by Porter McCray. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

———. (1951). Museums and temporary exhibitions. Museum International 4(1), 5–10.

Parra-Martínez, José and John Crosse. (2018, December). Grace Morley, the San Francisco Museum of Art and the early environmental agenda of the Bay Region (193X–194X). Feminismo/s 32, 101–134.

Works Cited

A brief history of the museum. (1999). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Benedetti, Joan M. (2003). Managing the small art museum library. Journal of Library Administration, 39(1), 23–44.

Dadi, Iftikhar. (2012, October 1). Curating South Asia. Guggenheim UBS MAP.

Holz, Dayna, and Jessica Lemieux. (2007, July). Finding aid to the San Francisco Museum of Art, Office of the Director records, 1935–1958. SFMOMA.

Kirk, Kara. (2017, February). Grace McCann Morley and the modern museum. SFMOMA.

Martenyi, Megan. (2017, August). [ https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/wide-open-publics-tracing-grace-mccann-morleys-san-francisco/ Wide open publics: Tracing Grace McCann Morley’s San Francisco]. SFMOMA.

Miller, Arthur (1940, July 14). The art thrill of the week. Los Angeles Times, 8.

Morley, Grace L. McCann. (1960). Art, artists, museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art. (Suzanne B. Riess, interviewer). University of California Regional Cultural History Project.

———. (1939, September 12). Letter from Grace L. McCann Morley to Evelyn Ahrend. Spanish Refugee Relief Association Record, 1935–1957, Part B: General Office Files Box 25: Picasso Tour. The Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library, NY.

The Museum of Modern Art history. (n.d.). MOMA.

Straus, Tamara. (2010, January 10). Grace Morley—Forgotten pioneer behind SFMOMA. SF Gate.