Bishop Mark J. Hurley and the San Francisco State College Strike, A Personal History: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by William Issel, Professor of History Emeritus, San Francisco State...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

[[category:SFSU]] [[category:OMI/Ingleside]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:African-American]] [[category:Dissent]] [[category:riots]] [[category:Bay Area Social Movements]] [[ | [[category:SFSU]] [[category:OMI/Ingleside]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:African-American]] [[category:Dissent]] [[category:riots]] [[category:Bay Area Social Movements]] [[category:Power and Money]] [[category:Churches]] [[category:Schools]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:17, 7 December 2021

Historical Essay

by William Issel, Professor of History Emeritus, San Francisco State University

This is a condensed and revised version of the author’s article published in American Catholic Studies Fall 2015, Vol. 126, No. 3 (Fall 2015), pp. 1-23, published by American Catholic Historical Society and available at JSTOR.

Countless Irish ancestry Catholic liberals helped shape the political culture of San Francisco from Gold Rush times to the present. The story of Irish Catholic liberal Bishop Mark J. Hurley and the strike at State is an important chapter in a genuinely inclusive history of the city of San Francisco. The Hurley story is also a chapter in the long history of how white allies have participated in and aided the freedom struggle of nonwhite peoples in the United States from the eighteenth century to the present. Hurley helped minimize violence during the nearly five-month long Black Power-inspired strike by the Black Student Union (BSU) and Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) at San Francisco State College in 1968 and 1969. He also brokered the settlement of the strike, a settlement he based on the principle that peace is not merely the absence of conflict but also the presence of justice. The settlement that the Bishop facilitated helped the striking students move forward their project of establishing a School of Ethnic Studies at the college, the first of its kind in the United States. The magnitude of the Bishop’s participation in these events was unknown to the public at the time and has not been acknowledged in recent accounts of the San Francisco State and other Black and Third World student campus revolts during the Sixties and Seventies.(1)

I was a 28 year old assistant professor at State in the fall semester of 1968, having returned to teach at my alma mater after living in the East completing my graduate work, teaching at the Camden, New Jersey campus of Rutgers University, and then coordinating and supervising the history teachers in a Great Society program at thirteen historically Black colleges in the South. Like most San Franciscans during the 134 day strike, I knew from local newspapers and television that Hurley was chairing a citizen’s committee appointed by Mayor Joseph L. Alioto to seek a peaceful resolution of the strike. But like the general public and San Francisco State students and faculty, I was unaware of the extent of the Bishop’s involvement because he deliberately worked quietly behind the scenes and avoided publicity. Only the members of his committee, a few staff members in the mayor’s office, and a handful of more senior faculty at the college were privy to the importance of his activities. The leaders of the student strike were aware of the Bishop’s role because they enlisted his help in settling the strike, but they chose not to acknowledge his participation at the time, or thank him for his work, and strike veterans have failed to give credit to him in the various commemorations of the strike they have held since March 1969. It was a chance encounter with one of my senior colleagues at the college that sent me on a search for evidence about this Catholic Bishop’s role in a Black Power-inspired campus revolt that became the longest student strike in United States history.

That chance encounter took place twenty years after the strike at the “Old Boys’ Table” in the faculty club at San Francisco State University, where you could sit if one of the “Old Boys” invited you. Since I was then serving on the Academic Senate and had gotten to know several of these more senior colleagues I was sometimes invited to join the table talk. One day, Eric Solomon, an English professor who had been active in the strike and later served as assistant to the president asked me what I was working on. I explained that in doing research for a book on San Francisco politics since the Great Depression I was exploring the role of the Catholic Church and Catholic lay activists in the city’s political culture. Eric put down his knife and fork and exclaimed “Catholics, eh? I can tell you something about that! If it hadn’t been for the Bishop, The Strike might have gone on longer than five months.” (Simply “The Strike” was how all of us who had been there referred to those hectic weeks of high emotions, bitter debates among a deeply divided faculty, three-foot long club-wielding “Tactical—Tac—Squad” police officers, and demonstrators en masse, fists clenched and arms held high chanting “On Strike, Shut it Down.”)

As Eric was saying this, I recalled one of the few notes of humor that marked the otherwise fraught and tension-filled university “convocations” in late November of 1968. The strike that began on November 6 had been underway for several weeks, and some 700 faculty filled the university’s largest auditorium; the administration had just announced its latest response to the strike leaders’ fifteen “non-negotiable demands” and it was time for speakers from the floor to comment. A tall Philip Roth look-alike strode down the aisle and grabbed the microphone from the hands of a startled female colleague waiting to be invited to speak. “My name is Solomon,” this professor announced in a forceful Boston-accented voice, “and I am going to tell you how to resolve this matter.” A stunned silence followed, and then—after those in the audience who “got” the joke stopped laughing—Eric proceeded to add yet another personal prescription to the dozens already submitted for how to best settle the strike. (2)

Eric brought me back to the present when he told me “You need to make sure you talk to the Bishop and get his side of the story,” and I made a mental note to add Bishop Mark J. Hurley to my list of people to interview. Hurley died in early 2001 and the interview never took place, but his papers at the Chancery Archives, along with several collections in the Northern California Labor Archives and Research Center, and interviews, confirm and even extend what Eric Solomon had to say about the importance of the Bishop’s role in the strike.

Bishop Mark Joseph Hurley and Catholic San Francisco

Bishop Hurley’s role in minimizing violence on campus and brokering the settlement of the strike came to him by virtue of his being a consummate insider in what was then, but is no longer, a very Catholic San Francisco. Mark Joseph Hurley was born in 1919, one of five children of a father born in Massachusetts to immigrant parents and a mother who was born in Ireland. Mark’s brother, Frank T. Hurley also entered the priesthood and eventually served as Archbishop of Anchorage, Alaska. The Hurley family enjoyed a middle class San Francisco Irish Catholic life in the Ashbury Heights neighborhood overlooking Golden Gate Park. They worshipped at St. Agnes Church located across the street from the “Panhandle” of Golden Gate Park, and Mark attended the parish school. After graduating from St. Agnes School, he moved some 30 miles south to Mountain View and then Menlo Park. There he undertook an eleven- year odyssey that took him through St. Joseph’s College for his high school degree, St. Patrick’s College for his AB degree, and St. Patrick’s Seminary, where he graduated in 1944. He was ordained in 1944, and then spent an academic year at Berkeley while serving as assistant superintendent of archdiocesan schools. He then moved across the country to The Catholic University of America (CUA), earning a Ph.D. in 1947; CUA Press published his dissertation Church–State Relationships in Education in California in 1949. (3)

Hurley was one of the brightest stars in a constellation of young priests hand-picked by Archbishop John J. Mitty for leadership roles in what he liked to call his archdiocesan Catholic Action crusade. It was a time when, as Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote in his 1989 memoir “the San Francisco Archdiocese sent more graduate students to the Catholic University than any other diocese in the country.”(4) One of Archbishop Mitty’s Catholic Action initiatives was “the education apostolate,” and Hurley took a leading role in this effort beginning in 1944, when the Archbishop named him to the assistant superintendent post, the first of a series of positions where he supervised the teaching of Catholic values in Bay Area schools. In addition to a year as a teacher at Juniperro Serra High School in San Mateo, Hurley served seven years as founding principal of the Bishop O’Dowd High School in Oakland and two years as founding principal of the Marin Catholic High School in Kentfield. In 1962, the year he was named Monsignor by Pope John XXIII, Hurley became one of the “experts” sent to the Vatican Council, serving on the Commission on Seminaries, Universities, and Schools until 1965. Back in San Francisco, he participated with Rabbi Alvin Fine and Episcopal Bishop Kilmer Myers in a popular local television talk show “Problems Please,” where he became known as “the young Fulton Sheen” due to his “wit, warmth, brilliance and striking appearance.” Hurley claimed that his January 1968 consecration as Auxiliary Bishop “marked the first time that Jewish, Protestant, and Orthodox churchmen were accorded equal rank with the Catholic prelates” in such an event, which he interpreted as an expression of the “new humanism stirred in the Catholic church by the Vatican council.” Monsignor George G. Higgins, Director of the Social Action Department of the U.S. Catholic Council preached the sermon at Hurley’s first Pontifical Mass.(5)

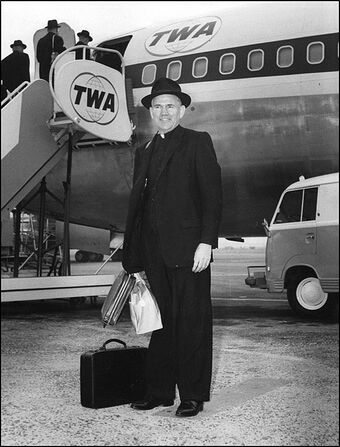

Bishop Hurley returning from Vatican II, 1965.

Photo: Courtesy of the Chancery Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco

Hurley was part of a larger network that included both religious and lay activists whose work from the 1930s through the 1960s imparted a distinctive Catholic slant to San Francisco’s political culture. Hugh A. Donohoe became the first Bishop of Stockton after serving as Auxiliary Bishop in San Francisco and chaplain to the city’s Association of Catholic Trade Unionists (ACTU). Monsignor Joseph Munier oversaw Catholic Action training for priests at St. Patrick’s Seminary and participated in the joint Allied Occupation Administration-Vatican project to revitalize Catholicism in West Germany. Monsignor Bernard Cronin served as chaplain to the Oakland ACTU and was director of the archdiocesan postwar refugee resettlement work.(6)

Several lay and religious members of the Catholic Action network played leading roles in racial justice reforms in the 1950s. Mayor George Christopher appointed Terry Francois, a Black Catholic civil rights activist and John F. Henning, a white Catholic labor activist, to the newly established Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity (CEEO) in 1957. Seven years later, Mayor Jack Shelley, who was himself a stalwart member of Catholic Action, appointed Sister Maureen Kelly to the city’s new Human Rights Commission. When Sister Kelly left San Francisco after her first year, Shelly replaced her with Sister Bernadette Giles, who served 16 years on Commission. Like Shelley, Joseph L. Alioto, who followed him in the Mayor’s office, was a longtime supporter of Archbishop Mitty’s Catholic Action initiative, and both Shelley and Alioto maintained close working relationships with Mitty’s successor Archbishop Joseph T. McGucken. Their mayoral terms ran from January 1964 through December 1975, and at no time during those rather boisterous years in the city’s history did they fail to bring to their duties a consistent commitment to a Catholic faith-based agenda in city affairs. In addition to their close working relationship with the chancery office, Shelley and Alioto also maintained strong alliances with San Francisco’s labor unions, with their heavily Catholic rank and file, alliances that like their Catholic Action activism extended back to the late 1930s.

The Citizens’ Committee of Concern

The student strike began on November 6, and after the first week, guerilla warfare tactics by strike supporters (rock throwing and firebombing) and police violence (unwarranted clubbing and beating) were becoming a daily occurrence.(7) Mayor Alioto turned to the Church and to the labor movement for help. George Johns, executive secretary of the San Francisco Labor Council, who was also a member of the advisory board for Robert Smith, the president of the college, urged Alioto to appoint a “blue ribbon committee” of private citizens; they would serve as mediators, create a resolution acceptable to all sides, and restore civility to the campus and order to the college’s affairs. Alioto asked Archbishop McGucken to help, and McGucken delegated Auxiliary Bishop Hurley. Hurley was elected chairman at the first meeting of the new “Citizens Committee of Concern.” (8)

Bishop Hurley chairing a meeting of the Citizens Committee of Concern. From left: Al Dere, Bishop Hurley, William Chester, Ronald Haughton, 1969.

Photo: Courtesy of the Chancery Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco

Joining Hurley on the Committee were numerous Liberal Democrats, some Catholic and some not Catholic, who had supported Jack Shelley during his mayoral term of office and backed Alioto during his first campaign in the summer and fall of 1967. This group included Catholics Leo McCarthy, a member of the Board of Supervisors, and Joseph Belardi, president of the Labor Council, as well as non-Catholics Alvin Fine, presiding rabbi of Temple Emanuel-El, and William Becker of the Jewish Labor Committee and the Human Rights Commission. Hurley’s Committee also included several former Communist Party members who had left the party in disillusionment after Nikita Khrushchev revealed “the crimes of the Stalin era” in 1953, including Revels Cayton, a Black official in the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) who was serving as Alioto’s deputy director for social programs. Soon Hurley and Becker, who served as executive secretary, were putting in fourteen hour days, working behind the scenes to mediate between the imperious and self-righteous college president, S. I. Hayakawa, and the suspicious and intransigent BSU and TWLF student strike leaders.

In his first public statement as chairman, the Bishop took issue with media accounts of the committee that characterized him and his group as empty suits who would be doing the bidding of the mayor and “the Establishment.” Hurley insisted that his committee “while initiated by Mayor Alioto in the public interest, does not consider itself the representative of any group.” He promised that it would work as “a neutral body seeking to initiate true dialogue among the contending factions: to seek solutions to honest and documented grievances; and to effect reconciliation within not only the educational community but in the community at large.” The Bishop insisted that the striker leaders had legitimate grievances that needed to be honestly and effectively addressed. He criticized media commentary that was condemning the strike as the product of “outside agitation” and “Communistic influences.” Hurley and the Catholic chaplain of the college, Father Peter Sammon, told the public that a fair settlement of the strike had to address: ending racial discrimination in college admissions practices and personnel matters; creating courses and programs that served the needs of underrepresented students; insuring fair play in the case of George Mason Murray.(9)

Black Power, 1967–1968

The case of George Murray, and the strike at State more generally, took place in the context of the revolutionary phase of the Black Power movement in 1967 and 1968. George Murray was a 23 year old graduate student, part time instructor of an experimental special admission/educational opportunity English course, and member of the Black Student Union. He was one of a cadre of BSU activists inspired by James P. (“Jimmy”) Garrett, a Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) veteran who had moved to San Francisco State expressly to organize a Black Power political and cultural presence in a major US college.10 On November 6, 1967, Garrett, Murray, and several other BSU members, offended by an editorial in the student newspaper assaulted its white editor in his campus office. They were suspended from the college but their suspensions were later lifted by the then college president John Summerskill. Murray was arrested for the assault, pled no contest to the charges, was convicted and sentenced to a six month jail term, and then his sentence was suspended and he was given probation. (When Garrett was arrested he had a gun in his possession and was then charged with a felony; offered the choice between leaving San Francisco or a long prison sentence, he relocated to Washington, D.C.).

Murray’s case and that of the others arrested for the assault became the subject of student demonstrations on campus in November and December, and in February President Summerskill submitted his resignation, to be effective in September. From March through May, the BSU, the TWLF, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and Progressive Labor Party (PLP) carried out campus demonstrations and sit-ins to end the college Air Force ROTC program and to immediately increase the number of students enrolled in the special admissions program, increase the number of Black, Latino, Asian American, and Native American instructors in Black Studies and Ethnic Studies courses, and support the cases of several temporary instructors who claimed they had not been rehired due to racial discrimination. State college trustees responded to these televised disruptive events by demanding that Summerskill’s resignation take effect May 24, and on June 1 they appointed Robert Smith in his place. George Murray taught in the spring semester, and he was rehired to teach again in the fall semester.

George Murray was also Education Minister of the Black Panther Party, and he visited Cuba during the summer of 1968 as part of a Panther delegation. He condemned United States intervention in Vietnam while in Cuba, declaring that “Every time an American mercenary is shot [in Vietnam] that’s one less cat that going to be killing us in the United States.”(11) After he returned, Murray published a manifesto “For a Revolutionary Culture” in the BPP newspaper The Black Panther filled with positive references to revolutionary nationalist terrorism in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, arguing that it ought to serve as a model for Black revolutionary theory and practice in the USA. “Our paintings must show piles of dead businessmen, bankers, lawyers, senators, congressmen, burning up inside their stores, being blown up in cafes, restaurants, night clubs.” He stressed “we need Black power and political power comes through the barrel of guns” and he warned his readers that without a revolution “there will be a tomorrow full of concentration camps, gas furnaces, and the screams of our mothers and little sisters. Black men, Black people, colored prisoners of America, revolt everywhere! Arm yourselves. The only culture worth keeping is a revolutionary culture. Change. Freedom everywhere. Dynamite! Black Power. Use the gun. Kill the pig everywhere.” (12)

In a speech at Fresno State College, Murray explained “The Necessity of a Black Revolution,” beginning by asserting that it is a “fact that Black people are 20th Century slaves” and “that Lyndon Baines Johnson is a racist cracker punk.” Governor Reagan and state Superintendent of Schools Max Rafferty were “crackerjack racists” and “sissies like [Hubert] Humphrey.” He ended the Fresno State speech with “WE ARE SLAVES, AND THE ONLY WAY TO BECOME FREE IS TO KILL ALL THE SLAVE MASTERS!!!”(13) Murray continued such rhetoric after the California State College Trustees ruled that his discourse was unacceptable for a state college instructor and recommended on September 26 that he should be suspended from all teaching duties. President Smith refused to do so, and at San Francisco State a month later, Murray announced that “The only realistic way to deal with a cracker like [President Robert] Smith is to say we want 5,000 Black people here in February, and if he won’t give it to you, you chop his head off.” On October 28, the first anniversary of BPP leader Huey Newton’s arrest in connection with an Oakland shoot-out between the Panthers and the police, Murray led a BSU demonstration on campus in support of Black Power, during which he leaped onto a table in the cafeteria and led his supporters in chants of “Free Huey” and “Off the Pig.”

Two days later, the California State College Chancellor Glenn Dumke issued Smith an order to suspend Murray to take effect on November 1. Murray and the BSU had previously threatened a strike if he was removed from his teaching post, and now the BSU announced that a strike would begin on November 6, the anniversary of the attack on the Gater editor. Two days later the TWLF joined the strike. Both organizations pledged themselves to remain on strike until the college met their combined fifteen demands for more Black and ethnic studies classes and instructors, more special admissions students, the reinstatement of George Murray and several other ethnic studies instructors, and no disciplinary action against any striking students, staff, or teachers.

Murray immediately became a cause célèbre among civil libertarians who saw the Trustee’s and Chancellor’s actions as a violation of a teacher’s First Amendment rights and a violation of a college’s ability to control its own internal affairs. President Smith’s own sympathy for Murray was evident in his comment that he “was only twenty-three, the son of a minister, and a talented ex-square on a bad trip in the cauldron of race pressures.”(14) Murray was in fact the son of a minster, and he would later make a career serving the spiritual needs of his own congregation in a low-income Oakland neighborhood. But Smith’s suggestion that Murray was on “a bad trip” implied he was being acted upon by a toxic substance, a victim of unintended consequences, when in fact he and thousands of young Black (and white and otherwise) men and women had deliberately and actively opted out of nonviolent civil rights work in favor of confrontational Black Power action between the February 1965 assassination of Malcolm X and the murder of Dr. King in April 1968. They mistakenly believed that a revolutionary situation existed and decided to seek out opportunities to conduct an armed rebellion using “any means necessary” against what they regarded as a murderous fascist imperialist genocidal white America.(15)

I watched this kind of conversion from reformer to revolutionary happen before my own eyes while working in the Thirteen College Curriculum Program in Southern Black colleges and universities during the “long hot summer” of 1967 and through the winter, spring and summer of 1968. Most of us strongly disagreed with the notion that the United States was poised for revolution, and we “kept the faith” and continued to promote a reformist, not revolutionary, agenda as our bosses, Rev. Dr. Samuel DeWitt Proctor and Dr. Conrad Snowden, continually urged us to do in their version of locker room pep talks. Proctor quoted scripture verse that he would later use as the title of his memoir, Hebrews 11:1 “faith is the substance of things hoped for; the evidence of things unseen.” (16) But one after another of our colleagues, and students in our program, gave up on peaceful reform as we muddled through those months, shocked by media coverage of riots and retaliatory police killings in Newark and Detroit, Plainfield and Minneapolis, then traumatized all over again in February 1968 by what we insisted on calling “the Orangeburg Massacre” of three young men by police on the campus of South Carolina State University, one of the colleges in our program. No sooner had we recovered somewhat when Dr. King was murdered on April 4. Feelings were so high on the campus of Virginia State in Norfolk that day, where I was meeting with the teachers and students in our program, that the college president, who feared for our safety, escorted me and several other white teachers off the campus. The sense of crisis and a feeling that anything could and might well happen was palpable, whether in Atlanta during the funeral of Dr. King on April 9, or at the Church of St. Paul on Mt. Auburn Street near our Cambridge offices on June 6, kneeling alongside Black and white colleagues as we prayed for the soul of Bobby Kennedy.

In September 1968, I moved to San Francisco State, where I accepted a position as assistant professor in the History Department. It was clear during the first weeks of the fall semester that the just-beneath-the-surface anger against white people that coexisted with sorrow for fallen comrades that I had experienced on Black college campuses in the South also existed among Black Power and Third World Liberation activists at State. I had not been in San Francisco during the spring and summer, but I was aware that the BSU leadership was strongly influenced by a Black Nationalism and Third Worldism agenda influenced by Leninist and Maoist theorizing that attracted support from Latino, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and Native American student organizations allied in the TWLF. (17)

On the rainy morning in November when I walked onto campus as the strike began, I was still committed to the reformist universalistic principles that had brought me to Dr. Proctor’s program and strongly opposed to the revolutionary particularistic agenda of the student strike.18 After sixteen months of seeing the damage done in our program by angry shouted demands, self- righteous pious declarations of racial loyalty, and racially-based calls for victory "by any means necessary," I could not avoid concluding that Black Power as then practiced was deeply destructive to the possibility of respect-based conversation across ethnoracial borders, without which democracy was doomed. I was fully committed to the goal of expanding opportunities for students from what we called “underrepresented” populations, the goal I had been making a living pursing. I was also fully committed to promoting racial justice in campus operations of all kinds, from admissions, to hiring, tenure, and promotion, to curriculum design and implementation. But I was at the same time convinced that Black Power-inspired revolutionary rhetoric and insurrectionary-type action to achieve racial equality in college affairs was a dead end, not a just war. Already, I had lost former friends and fellow-workers, in their late 20s like myself, who had resigned from their jobs or quit their graduate school programs and who had armed themselves and were now misguided self-styled revolutionaries, traveling from one event to another seeking opportunities to “heighten the contradictions” and “live the revolution.”

Several headed to San Francisco after protesting at the August 26-29 Democratic Party convention in Chicago, and they joined the demonstrations on campus during the student strike at State. The striking students and the hundreds of non-students who joined their ranks during the strike were expressing a complex tangle of intersecting visions that defied simple Cold War binaries such as “outside agitation” versus “local activism” or “Communistic” versus “American” values. When I read in the San Francisco Chronicle that Bishop Hurley was to chair a citizen’s committee, I knew that his work would be complicated by the Black Power and Third World Liberation mentalities and the “America has become a fascist imperialist state” sentiments that fueled the emotional and ideological energy of the BSU and TWLF leaders and their white SDS and PLP allies. What I did not know, and was not to discover until much later, was how Hurley would draw upon his personal experience and his mediation skills to defy the odds and play a positive role in settling the strike.

The Strike at San Francisco State

By the end of the first week of the strike, a sort of “call and response” dynamic had become established at midday on the campus. Some demonstrators and provocateurs verbally and sometimes physically challenged and taunted the Tac Squad police officers; some police officers then caught, beat, and arrested selected students in response. In addition, bands of strikers descended on selected classrooms where instructors were teaching despite the strike and berated both professors and students for their alleged complicity with white racism. The “war of the flea” strategy of the strike leaders who embraced a guerilla warfare strategy (not all did) included such tactics as setting fires in campus lavatories, pitching large rocks through the office windows of faculty members who outspokenly opposed to the strike, and slashing the tires of the cars of such faculty members outside their homes. The ubiquitous newspaper reporters and television camera operators who chronicled the chaotic and violent campus events gave Wednesday November 13 the title “Bloody Wednesday,” which for those readers and viewers old enough to have been there, or to have heard the stories, evoked memories of the “Bloody Thursday” on July 5, 1934, when police shot and killed two men during the Waterfront strike of that year.

Convinced by the events of the day that the campus could not operate on a “rational basis” until the strike was settled, President Smith ordered the college closed at the end of the day, November 13, and it remained closed despite Governor Reagan’s displeasure and the trustees’ order to reopen five days later. Smith temporized by reopening the campus for departmental discussions and a university convocation of students and faculty instead of for classes, but on November 26 he resigned and English professor S.I. Hayakawa was named Acting President. Hayakawa’s first action was to close the campus, and when he reopened it on December 2 and the striking students placed a truck with a loudspeaker at the main entrance of the campus urging students to refuse to attend classes, the new president received nationwide publicity after TV cameras showed him climbing onto the truck and pulling out the wires connecting the microphone to the loudspeaker.

The next day, “Bloody Tuesday” began some two weeks that saw the campus roiled with conflict featuring demonstrations in the center of the campus, including angry speeches by an increasingly confident strike leadership that was buoyed up by the visits and speeches of several busloads of pro-strike Bay Area Black community leaders and public officials. The spirit of revolt ran so high among the BSU and TWLF leaders that they rejected out of hand a December 6 settlement offer from President Hayakawa that had been drawn up by the college’s Academic Senate and its Council of Academic Deans (CAD). Because this proposed settlement did not agree to the demand that “sole control” of special admissions, hiring of ethnic studies teachers and curriculum would rest with the students, staff, and faculty of Black studies and ethnic studies departments and programs, it was considered a violation of the Black Power principle of “self- determination” and deemed unacceptable. Leroy Goodwin, the BSU Off-Campus Coordinator vowed to “continue the struggle —if necessary—all year long—or as long as it takes to win all these demands.” On December 10, Goodwin issued “an official declaration of war. Under this state of war all ad hoc rules and regulations set up by the acting president, Hayakawa, to hamper freedom of speech or freedom of assembly will be disregarded, and the battleground tactics and time sequences will be determined by the central committee of our revolutionary people.”(19)

Progressive Labor Party activists joined in the declaration of war, deploying both revolutionary rhetoric and guerilla warfare tactics; they proudly embraced their Maoist affiliation, explaining that they “looked to the example of the Chinese revolution and have consistently maintained a principled position of no sell-out and no compromise with the ruling class on the basic fifteen [strike] demands, on amnesty for strikers and on the fight against racism.” Condemning Mayor Alioto, whom they characterized as “Big Joe” and “his cronies” the PLP urged the BSU and TWLF strike leaders to maintain their refusal to compromise. Their fifteen demands should remain “non-negotiable.” From the standpoint of the PLP, the strike was only one battle in “a revolution which smashes the present capitalist state apparatus” and “people have the right to defend themselves from the ruling class and their pigs by whatever means necessary.”(20)

Bishop Hurley and the Strike

On Monday, December 9, the day before Leroy Goodwin issued his declaration of war, Bishop Mark Hurley met with Father Peter Sammon of the college Newman Club to be briefed on the events at State over lunch at Bruno’s Restaurant, a popular gathering place among city officials and labor unionists located on Mission Street near the Labor Council office. (21) That morning, Archbishop McGucken had asked Hurley to represent him on the citizen’s committee that Mayor Alioto was moving forward with in association with George Johns, secretary of the Labor Council. After lunch with Sammon, Hurley and several dozen prospective committee members met at the Labor Council. The Bishop was elected chairman, and they issued a strong negative response to the request by the chairman of the state college board of trustees that they refrain from attempting to settle the strike. The next day, before Bishop Hurley’s committee held its first formal meeting, he and Black ILWU official William Chester met with Arthur Bierman and Peter Radcliff of the campus American Federation of Teachers Local 1352 (Local 1352) at the Del Webb Hotel near the San Francisco Civic Center. Some members of the union were convinced that if Local 1352 conducted a strike that they could help resolve the student strike, but the local needed official sanction from the Labor Council in order to launch a legitimate strike, and they would need to convince the Council that they were striking because of genuine work-related grievances, not in sympathy with the students.

Bierman and Radcliff were surprised when Bishop Hurley now urged them to request strike sanction and convince their fellow union members to go out on strike as a way to insure against further violence on the campus. He told Bierman and Radcliff that according to an arrangement between Mayor Alioto and the police, if an official union picket line existed on the sidewalks bordering the campus, the police would respect the picket line. They would stay outside the campus, except when responding to specific calls by the administration. They would not come en masse onto campus, and this would lessen the danger to students and bystanders posed by police overreaction to the provocateur heckling and rock throwing that had taken place on campus during the large demonstrations in the Quad in the November 6 to December 13 period. Hayakawa had already banned speeches and marches on the campus itself, and since it had been the police marching en masse into the interior of the campus that had generated the pitched battles of the “Bloody” days of November 13 and December 3, violence could be expected to decline. Hurley described the rationale behind his request of Local 1352, which he later reiterated to a meeting of Latino community leaders in the Mission district, in a lengthy November 2, 1969 interview, a passage from which deserves to be quoted verbatim:

I brought up to them that I considered this strike extremely dangerous. I mentioned I had been in Nicaragua—this seems like going far afield but this is exactly what I told them. I had been in Nicaragua July 23, 1959, was standing watching a student demonstration and I stood within twenty-five feet of the military and watched them shoot down 35 boys, 12 of whom died and I gave the last sacraments to them. This had never happened in the history of Nicaragua before, no one expected it. It was an unusual event. It did not happen every day. The boys who were shot down were by and large the sons of men in the government. So it was the government shooting their own sons in effect. I considered this strike a terribly dangerous situation at State and therefore thought it worth our efforts to get a settlement.(22)

Local 1352 voted to strike the next day, December 11, and some 50 AFT members then mobilized a picket line at the front entrance of the campus. Hurley and his committee held its first official meeting and the Bishop now reiterated Father Sammon’s earlier call for fairness to the students. He reminded the public that “much history, social and otherwise, has converged upon this one campus” and he emphasized that as the committee worked to bring “peace on the campus” it would do so mindful of the principle that genuine peace needed to be “the fruit and direct result of justice.” (23) Hurley convinced the committee members to add representatives from the student government organizations at local colleges and to add a professional Black mediator to the committee. Three days later, he flew to Washington, D.C. and recruited Samuel Jackson, Vice President of the American Arbitration Association. Jackson then joined Ronald Haughton in a biracial team of professional mediators who met with the committee; the Ford Foundation agreed to pick up the tab for their salaries and expenses while in San Francisco.(24)

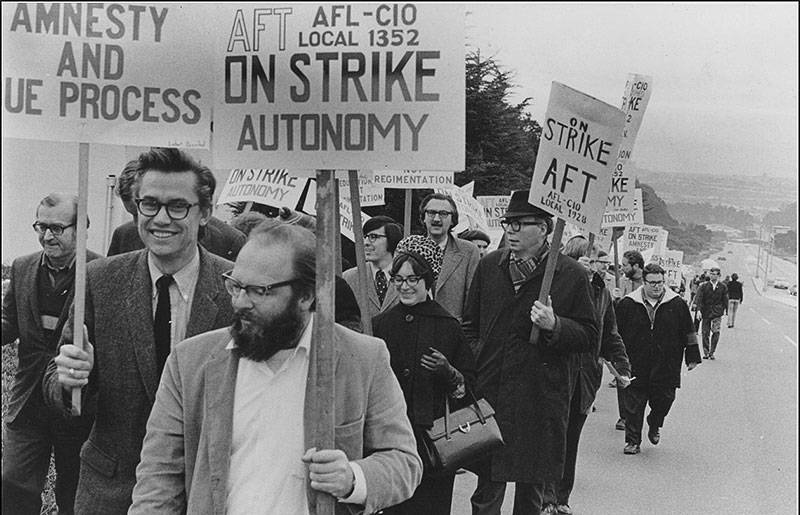

Arthur K. Bierman and Peter Radcliff leading a Local 1352 picket line during the strike, date unknown.

Photo: Phiz Mezey, courtesy of the Labor Archives and Research Center, San Francisco State University

On December 13, Hayakawa shut down the campus early for the Christmas and New Year’s holidays. When classes resumed on January 6, Local 1352 pickets, Arthur Bierman, Peter Radcliff, and Eric Solomon among them, sometimes joined by students, walked the picket line with official AFL-CIO approval. Because police did not come en masse onto the campus after December 13, the pitched battles with students that had caused so much violence between November 6 and December 13 did not occur again. Police officers did come on campus to apprehend and arrest specific individuals and to respond to requests for assistance by administration officials. I witnessed several such events myself, and some strike veterans today recount having experienced unwarranted use of force by police officers in such instances after December 13. However, Hurley’s strategy of using an official AFL-CIO picket line succeeded in keeping a large force of police off the campus and protecting students and faculty from the police violence that had marked the first month of the strike. Even on January 23, when police did come back onto the campus in force to arrest 453 demonstrators and bystanders after a rally took place in violation of Hayakawa’s order banning demonstrations, they did not repeat the clubbing and beating that took place during the earlier part of the strike. (I spent a sleepless night after that mass arrest raising bail money and bailing out a student who had been caught up in the mass arrest).

Through the holidays and during January and February, Bishop Hurley worked to establish a personal connection with the BSU and TWLF leaders. He was a presence on campus for five weeks, sometimes walked with student strikers when they joined the Local 1352 picket line, listened to their grievances, and urged them to discuss specific proposals for settling over the fifteen demands. He met three times with strike leaders in the rectory of his North Beach parish church, St. Francis of Assisi, stressing the need for compromise and urging them to adopt the mentality of reformers and discard the mentality of revolutionaries. Then, one week after the AFT voted to end their strike, on March 5, a BSU member named Timothy Peebles seriously injured himself while trying to blow up the campus Creative Arts Building. Peebles had brought a bomb into the building during a rehearsal that night, in a quantity sufficient to destroy most of the structure; he survived, and the strike ended with no fatalities. This event was the tenth of a series of bombing attacks dating to the early days of the strike, and the second that resulted in injury to a striker, strike sympathizer, or other person, rather than in damage to college property or the property of alleged collaborators with the college administration. The incident seriously damaged the credibility of the strikers among their faculty supporters, the student population, and the general public.

In the days that followed, BSU leaders came again to the St. Francis of Assisi rectory and asked the Bishop to meet with them and George Murray in the county jail. Police had arrested Murray after stopping him and claiming that they found two loaded guns in his car; he denied the guns were his but he was now in jail for violating his parole. Hurley and Curtis Aller, chairman of a select committee of faculty that Hayakawa had appointed to represent him in negotiations with the BSU and TWLF, drove to the jail and met with Murray and the BSU leadership.

Murray asked the Bishop to intercede on his behalf with the college and the district attorney, saying that since they were “his parishioners” they would act favorably on Hurley’s request. Hurley replied that while he could not promise it would work, he would do all he could to seek Murray’s release from jail and amnesty for students who were facing criminal charges of assaulting police officers during the strike. Now, in contrast to their confidence back on December 9, Murray and the student leaders were exhausted by the weeks of struggle, and they realized how much their moral authority had been weakened by the Peebles bombing fiasco. George Murray removed the demand that he be rehired at the college, the BSU and TWLF agreed to negotiate a settlement of the strike along the lines of the December 6 proposal, and the Bishop agreed to oversee the drafting of a settlement pact.(25)

By the middle of March, Hurley’s efforts to facilitate peace with justice bore fruit when he chaired a meeting in President Hayakawa’s office during which all the parties endorsed the settlement terms. This led to the end of the strike on March 21. Bishop Hurley continued to meet with the college administrators in an effort to gain amnesty for George Murray and other strike leaders, but in the middle of a tense meeting he had to be taken to St. Mary’s Hospital on account of a painful bleeding ulcer. He was in the hospital and out of commission for several weeks. His absence had consequences, because without his forceful advocacy, the college administration declined to ask the District Attorney’s office to withdraw criminal charges against a number of strike leaders. Hurley later expressed his regret that he had been unable to prevent several convictions. George Murray was released after two and a half months in jail after promising to turn away from Black Power and revolution and to stay off college campuses. (26)

When assessing the settlement in 1970, Robert Smith, Richard Axen, and DeVere Pentony wrote: “An analysis of the terms of the settlement . . . reveals little that the striking Third World students gained by continuing the confrontation three months beyond the occasion of the first Academic Senate-CAD-Acting President Hayakawa offer on December 6. In fact, a strict accounting would probably indicate an overall loss.” Sociologist Fabio Rojas went even further in his 2007 history of Black Studies programs; he concluded that what happened at the end of the strike at State was that “Hayakawa Defeats the BSU.” (27)

Conclusion

For over fifty years a tale has been told about the strike at San Francisco State College. According to this tale, the bravery and audacity of striking Black and Third World student radicals, and the support of like-minded community activists, made possible the establishment of the first School of Ethnic Studies in the nation.(28) This article restores Bishop Mark J. Hurley to the story of the strike at State, presenting another, more fully-informed account of what really happened, an account that allows us, in the words of historian Timothy Snyder, “to appreciate the irreducible complexity of individuals and encounters” (29) in the longest student strike in United States history. Bishop Hurley’s mindset was shaped by his white Irish Catholic liberalism and by his experiences as an insider in the city’s distinctive tradition of Catholic mediation of social conflict. He was also influenced by the spirit and the specific anti-racist language of Pacem in Terris, the 1963 encyclical letter of Pope John XXIII. BSU and TWLF leaders, while disagreeing among themselves on tactics, shared a mindset shaped by their experiences as outsiders impatient with the city’s defacto segregation and institutional racism. They were also influenced by the spirit and the specific anti-racist language of The Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon, first published in English also in 1963. The strike leaders were initially reluctant to engage with Bishop Hurley, but his persistence paid off when George Murray and the BSU and TWLF leadership invited him to meet with them in the city jail and then asked him to draft the document and to oversee the discussions that led to the settlement that ended the strike on March 21, 1969.

Notes

1. Jason Michael Ferreira, “All Power to the People: A Comparative History of Third World Radicalism in San Francisco, 1968–1974,” Ph.D. diss., University of California Berkeley, 2003; Fabio Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007); Ibram H. Rogers, The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstruction of Higher Education, 1965 – 1972 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); Martha Biondi mentions Hurley in her chapter on State, but she misidentifies him as the archbishop and does not describe the scope and significance of his work in her The Black Revolution on Campus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); Hurley participated in the production of a volume about the strike at State that was published under the names of three administrators at the college: Robert Smith, Richard Axen, DeVere Pentony, By Any Means Necessary: The Revolutionary Struggle at San Francisco State (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1970). That detailed 330-page book, which appeared in a higher education administration book series, remains an invaluable primary source.

2. A telephone interview with Eric Solomon, Feb. 2, 13, 2013, confirmed these details.

3 Biographical information about Hurley is from his personal record file at the Chancery Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, Menlo Park, CA (hereafter CAASF).

4. John Tracy Ellis, Faith and Learning: A Church Historian’s Story (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1989), 72.

5. San Francisco Chronicle, Oct. 30, 1967; San Francisco Chronicle, Jan. 3, 1968; The Monitor, Jan. 4, 11, 1968.

6. Material in this and the following paragraph draws on William Issel, Church and State in the City: Catholics and Politics in 20th Century San Francisco (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013).

7. See By Any Means Necessary, passim. I witnessed all of these types of behaviors, as well as verbal assault and intimidation by strikers and overbearing arrogant behavior by police officers. Details can be found in the published work on the strike cited in footnote eight below.

8. Joseph L. Alioto to George Johns, December 10, 1968, San Francisco State College folder, Mark Joseph Hurley Papers in CAASF (Hereafter Hurley Papers); Citizens Committee on San Francisco State College Minutes, Dec. 11, 1968 (hereafter Minutes), Hurley Papers; general information not specifically cited in this and subsequent paragraphs is based on the author’s personal files assembled during the strike, and William Issel, Wesley Kyles, Frank Sheehan, Helene Whitson, On Strike! Shut It Down! A Revolution at San Francisco State: Elements of Change (The Leonard Library of San Francisco State University, 1999); William H. Orrick, Jr., College in Crisis: A Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence (Washington, D.C.: National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, 1969); William Barlow and Peter Shapiro, An End to Silence: The San Francisco State College Student Movement in the ‘60s (New York: Pegasus, 1970); Dikran Karagueuzian, Blow It Up! The Black Student Revolt at San Francisco State College and the Emergence of Dr. Hayakawa (Boston: Gambit, 1971).

9. Bishop Hurley: The Monitor (the archdiocesan newspaper), Dec. 19, 1968; Father Peter Sammon: The Monitor, Nov. 21, 1968.

10. Jimmy Garrett, interview transcript, 1969, Records of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, Series 57, Box 13, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library, University of Texas; Ibram Rogers, “Remembering the Black Campus Movement: An Oral History Interview with James P. Garrett, The Journal of Pan African Studies, 2 (2009): 20-41; Mr. Murray, and most of the other student strike leaders, did not respond to my requests for an interview.

11. Murray quoted from his Havana speech in an article, “Panthers’ Fight to the Death Against Racism,” that appeared in Rolling Stone, April 5, 1969, 14.

12. George Murray, “For a Revolutionary Culture,” The Black Panther, Sept. 7, 1968.

13. The Fresno State speech was published under the title “The Necessity of a Black Revolution,” The Black Panther, Nov. 16, 1968.

14. By Any Means Necessary, 109.

15. Peniel E. Joseph, Waiting ‘Til The Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006), passim.

16. Samuel DeWitt Proctor, The Substance of Things Hoped For: A Memoir of African-American Faith (New York: Putnam, 1995). Dr. Proctor, a Baptist minister and former president of North Carolina A & T University in Greensboro, kept the faith and left our program to head up a new special admissions program at University of Wisconsin, Madison. Then he became the first occupant of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Chair in the School of Education at Rutgers. Proctor had been one of Dr. King’s mentors. While at Rutgers, Proctor served as pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, taking over when Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. retired.

17. For recent scholarship on the BPP – San Francisco State College connections, see Donna Jean Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010) and Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013). For the national and international context, see Brenda Gayle Plummer, In Search of Power: African Americans in the Era of Decolonization, 1956 – 1974 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013) and Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che (New York: Verso, 2002).

18. These issues continue to be debated. See Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity, Creed, Country, Color, Class, Culture (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), and his Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers) (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006); Adolph L. Reed, Jr., “Black Particularity Reconsidered,” in Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., Ed. Is It Nation Time?: Contemporary Essays on Black Power and Black Nationalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Jeffrey Stout, Democracy and Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004); Tommie Shelby, We Who are Dark: The Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005); Michael C. Dawson, Blacks In and Out of the Left (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013); Eric Mann, “Lost Radicals,” Boston Review, Jan/Feb 2014, 60- 64.

19. By Any Means Necessary, 229; telephone interview by Bill Issel with Daniel Phil Gonzales, May 13, 2014.

20. “Alioto: Isolate the Maoists” a Progressive Labor Party pamphlet, copy in the San Francisco State College folder, Hurley Papers.

21. This and the next paragraph are based on a transcript of an interview by Curt Aller with Bishop Mark Hurley, November 2, 1969, Hurley Papers, a transcript of an oral history of Arthur K. Bierman by Peter Carroll, Jan. 14, 17, 28, 1992: 97-103, 130-139, Bierman Collection, Northern California Labor Archives and Research Center, San Francisco, CA, and email letters from Arthur K. Bierman to Bill Issel, Feb. 26, Feb. 27, April 8, April 9, 2014.

22. Aller interview with Hurley, 14; Marianne Means, “S.F. Priest Tells Leon Massacre,” San Francisco Examiner, Aug. 2, 1959.

23. Bishop Hurley’s statement to the press: The Monitor (the archdiocesan newspaper), Dec. 19, 1968; Father Sammon’s article: The Monitor, Nov. 21, 1968.

24. Minutes, Dec. 11, 1968.

25. Handwritten notes on the meeting in jail by Bishop Mark Hurley, March 13, 1969, in SFSC Agreements folder, Hurley Papers; Gonzales interview; email letter from Martha Biondi to Bill Issel, April 16, 2014; J. Hart Clinton to Right Rev. Bishop Mark J. Hurley, May 19, 1969, San Francisco State College correspondence folder, Hurley Papers.

26. Minutes, April 1, 1969; By Any Means Necessary, 313-315; Gonzales interview; The Black Revolution on Campus, 73-74.

27. By Any Means Necessary, 310-315; From Black Power to Black Studies, 83. The terms of the settlement are detailed by former San Francisco State University archivist Helene Whitson in her article, accessed December 6, 2021.

28. See Margaret Leahy, “On Strike! We’re Gonna Shut it Down: The 1968 – 69 San Francisco State Strike,” in Ten Years that Shook the City: San Francisco 1968 – 1978 (San Francisco: City Lights Foundation, 2011), 15-29, and the [ http://ethnicstudies.sfsu.edu/fortieth08 website of the San Francisco State University 40th Anniversary commemoration of the strike], Nov. 3, 2014.

29. Timothy Snyder, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (New York: Random House, 2015), xiii.