1901 General Strike on San Francisco's Waterfront

Historical Essay

by Laurence H. Shoup

originally published as Chapter 11 in Rulers and Rebels: A People’s History of Early California 1769-1901 (Author's Choice Press: New York 2010)

Short summaries of the 1901 Strike and the Employers' Association are available.

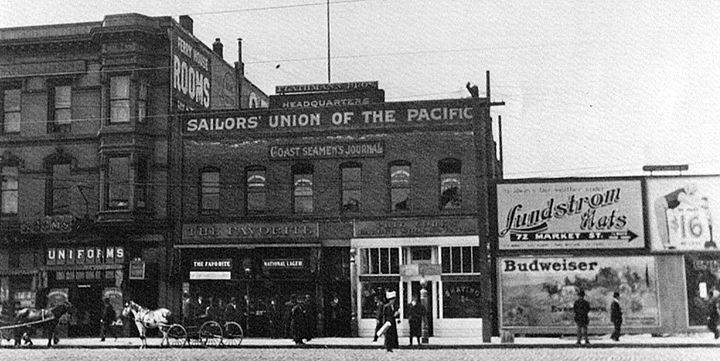

Sailors Union of the Pacific building, c. 1900.

Photo: Sailors Union of the Pacific

Only seven years after the defeat of the American Railway Union's 1894 strike, a massive, three month long strike on the San Francisco waterfront resulted in a triumph for the rank and file and a strengthening of the labor movement. The strike began on July 30, 1901, when the City Front Federation, representing over 15,000 men from fourteen San Francisco waterfront unions, led by the Teamsters, the Sailors Union of the Pacific, and four different Longshoremen’s Unions, walked off the job. This strike was the largest and most significant in the history of California to this point in time.

Although the great waterfront strike of 1901 developed out of a complex set of circumstances unique to its time and place, at the heart of the struggle was the continuing story that new unions were claiming freedoms and asserting their human rights, while at the same time, most of the leaders of the ruling class of San Francisco were refusing to accept any role for the working class in economic decision-making.

Teamsters’ Upsurge September 1900

The strike’s immediate origins can be traced to the formation of the Teamsters’ Union in August of 1900. This event was to be of special importance for both the 1901 waterfront strike and the future of the San Francisco labor movement. Led by Michael Casey, the union was initially small, less than 50 members, but the men who drove the horse teams often worked more than twelve hours a day, some even 18 hours a day, seven days a week at low wages ($3.50 to $16 a week) and under very competitive conditions; virtually all of them were ready to assert their humanity and respond to the union call (Cronin 1943:40).

On Labor Day 1900, McNab & Smith, one of the leading draying firms, in an employers tactic typical for the time, tried to break the new union by firing drivers who refused to quit the union. Casey and the union men called upon the remaining drivers to strike the offending firm, and when, to the shock of McNab and Smith, almost 100 men went out, the employer settled after only one day, immediately reinstating the discharged unionists. In the wake of this quick victory San Francisco saw one of its fastest single union expansions ever. In the space of only a few weeks, about 1200 men joined the Teamsters’ Union, and in mid-September Casey and his membership demanded improved hours and working conditions.

The employers group, the Draymen’s Association, wanted a stabilization of the all-out cutthroat competition characteristic of the industry, so it was open to an agreement that would prevent new competitors from entering the field except as members of the Association. The Association was therefore willing to recognize the union, and on October 1, 1900 a detailed formal agreement was signed. The workers got a regular 12 hour day, with overtime pay for over 12 hours and for work on Sundays, as well as the union shop and an agreement that no assistance would be given to public drayage firms employing non-union men. In return the union agreed not to work for any firm which refused to join the Association or for a wage lower than set forth in the contract, thus helping to stabilize employer costs and assisting employers in forcing other firms to join the Drayage Association. This agreement tied the union and Association together in a mutually convenient effort to stabilize competition within the industry (Knight 1960:58-60).

Founding of the City Front Federation, Early 1901

Waterfront workers in San Francisco had often been divided, with various jurisdictional disputes causing conflict, especially between the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific and the several longshoremen’s unions. Recognizing that disunity among workers handed a powerful weapon to the bosses, in the fall of 1900 the Sailors and Longshoremen signed an agreement that not only delineated lines of jurisdiction in cargo handling, but also established a policy of mutual assistance by specifying that members of these unions would not cooperate with nonunion workers in receiving and discharging cargo. This led to an even stronger alliance, when in early 1901, a federation of all onshore and offshore waterfront unions, including the Teamsters, was formed. Called the City Front Federation, it was a labor body with formal, centralized authority. Its constitution authorized its president to order a strike vote of all member unions if an employer offensive made it “...necessary to order a general strike” (Knight 1960:61).

By the summer of 1901 the City Front Federation included fourteen unions, between 13,000 and 16,350 members, and had a treasury of $250,000 (Knight 1960:61; The San Francisco Examiner July 21, 1901:18). The Federation was anchored by the Sailors, the Teamsters and four longshoremen’s unions, but also included a number of smaller unions, such as the marine firemen, porters, packers and warehousemen, ship repair craftsmen, and harbor workers. Together they could largely control the transportation and commerce of San Francisco and therefore had formidable power to choke off the city’s economic life and force employers to recognize and negotiate with their unions.

The Founding of the Employers' Association , April 1901

Employer organizations of various types had existed in previous decades in San Francisco, but had become inactive. With unions growing more powerful in 1900 and 1901, the key capitalist businessmen of San Francisco concluded that they should organize a counteroffensive to roll back and destroy the growing democratic power that unions represented. In April of 1901, fifty militant employers formed a secretive organization known as the Employers' Association. The organization was to serve as the guiding anti-union body for the San Francisco ruling class. To make sure that ample funds existed to carry out their policies, each pledged $1,000 to the organization. As other employers joined, they were also required to post bonds as guarantees of their observance of the Association’s policies. In this way the anti-union strike-breaking fund of the bosses grew to an estimated $500,000 (Knight 1960:67).

Although a semi-secret organization, the Employers’ Association is estimated to have had a membership of over 300 firms, with influence over many more. The Association exercised centralized control over its member firms, forbidding any member from granting a union demand or settling any labor dispute without the express consent of the association’s executive committee. Table 11-1 lists the members of this executive committee, along with their key corporate connections.

| Member | Corporate Connection |

| Frederick W. Dohrmann Jr. | Secretary, Nathan, Dohrmann Company |

| A.A. Watkins | Vice President, W.W. Montague & Company; President San Francisco Board of Trade |

| Charles Holbrook | President, Holbrook, Merrill & Stetson; a director of United Railroads, San Francisco, Union Trust Company and the Mutual Savings Bank |

| Harvey D. Loveland | Vice President, Tillmann & Bendel |

| F.W. von Sicklen | Dodge, Sweeney and Company |

| Percy T. Morgan | President, California Wine Association; a director of California Fruit Canners Association |

| Isaac Upham | Payot, Upham and Company |

| Frank J. Symmes | President, Thomas Day Company, President of the Merchants Association; a director of Spring Valley Water Company and Central Trust Company |

| Edward M. Herrick | President, Pacific Pine Company and Grey’s Harbor Commercial Company |

| Akin H. Vail | Sanborn, Vail and Company |

| Joseph D. Grant | Murphy, Grant & Company, a director of Donohoe-Kelly Banking Company, Mercantile National Bank, Mercantile Trust Company and Natomas Consolidated |

| Jacob Stern | First Vice President of Levi Strauss & Company, a director of the Bank of California, Union Trust Company and North Alaska Salmon |

| S. Nickelsburg | President, Cohn, Nickelsburg & Company |

| Adolph Mack | Mack & Company. Also a director of City Electric Company |

| Andrew Carrigan | Vice President, Denham, Carrigan & Hayden Company |

| Henry D. Morton | Morton Brothers |

| J. S. Dinkelspiel | J.S. Dinkelspiel & Company |

| George D. Cooper | W. and J. Sloane & Company |

The Employers' Association was representative of the highest economic circles of San Francisco, with close ties to the Board of Trade, Merchants Association and many of the biggest and most important firms of the city. The presence of direct connections to United Railroads, the Spring Valley Water Company and the Bank of California, as well as several other leading banks, is especially telling, for these were among the largest and most powerful corporations in the state. Its one weakness was that it had no direct ties to what was by far the single largest and most powerful corporation of the time, the Southern Pacific Railroad. Based in San Francisco, the railroad would be affected by the developing class struggle and also had the most influence with Governor Henry T. Gage, who had served as one of its attorneys. Despite the absence of the SP, the Employers' Association was nevertheless an organization by and for leading ruling class circles of San Francisco. It could also be confident in the support of the mayor and city administration, due both to the natural tendency of capitalist government--Democratic or Republican-- to side with big vested interests and because the Democratic Mayor, James D. Phelan, was also a leading capitalist and had served on the same corporate boards of directors as some of the executive committee members.

'The Labor Council and Industrial Disputes in Other Trades

The San Francisco Labor Council had been founded in late 1892 with 34 affiliates. Although it had been on the decline during the next few years due to employer attacks and internal conflict, it revived after mid-1897. From then on, with business conditions improving, it grew rapidly (Knight 1960:31, 36). By early 1901 the Labor Council, led by Ed Rosenberg and W. H. Goff, had become a real force in San Francisco. Its efforts to organize all workers, regardless of skill level, made San Francisco preeminent among major American cities in the degree of unionization among less skilled workers. Unfortunately, this positive effort resulted in a division in labor’s ranks when the craft union oriented Building Trades Council, led by P.H. McCarthy, broke with the Labor Council, openly scorning its efforts to organize unskilled, more easily replaced workers (Knight 1960:63-64). Some of the individual unions that made up the Building Trades Council later supported the City Front Federation in its conflict with the Employers Association, but most did not, violating a key labor principle held by the more advanced elements of the labor movement, the need for solidarity and unity among workers and their organizations.

Other unions were also on the move. In May of 1901, conflicts broke out in both the restaurant and metal trades industry. More than a thousand restaurant workers struck for the ten hour day and 4,000 to 5,000 workers in the metal trades struck for the nine hour day. Other unions supported both strikes, but the Employers’ Association intervened in these conflicts, strengthening the will and the resources of the employers involved. Both strikes eventually fell well short of their goals, even though the strike in the metal trades went on for about ten months (Knight 1960:67-71, 90-91).

The Teamsters Locked Out, Mid-July 1901

With the lines of battle between organized capital and organized labor more and more sharply drawn, and neither side willing to budge from basic principles, it did not take much to set off a new and more explosive conflict. The spark was a seemingly small and unimportant dispute over handling the baggage of a religious group arriving in San Francisco to hold a convention. The Morton Special Delivery Company, a non-union firm, which did not belong to the Draymen’s Association, was to handle the baggage. It had, however, subcontracted part of the job to a firm that was part of the Draymen’s Association, but had union workers. Moreover, the Morton firm’s owner, Henry Morton, was a vigorous opponent of the Teamsters’ Union (The San Francisco Examiner July 21, 1901:18; Knight 1960:72). The Teamsters Union, therefore, decided not to handle the baggage, which was justified by their contract with the Draymen’s Association, which said that union drivers were to reject employment by non-union firms. The union not only wanted to foster the union shop in transportation, but also to push back against the strongly anti-union attitude of Morton Special Delivery. As Michael Casey put it: “We stand by the proposition not to work for or with those who have shown an unfriendly spirit toward union men. We stand by that resolution” (The San Francisco Examiner July 20, 1901).

The Draymen’s Association (and behind it the Employer’s Association) felt the Teamsters’ Union had to be challenged and crushed, and now they had an excuse. It said its agreement with the Teamsters would be rendered null and void if the Teamster members did not handle what Casey had labeled “hot cargo”. They began to dismiss and lockout all Teamsters who refused to obey the orders of their respective bosses to handle the baggage for Morton Special Delivery. The Draymen’s Association began to hire scabs to take the places of ousted workers and took a stand amounting to an ultimatum to the Teamsters: “quit the union or lose your job”. The Draymen were pressured to take this stand by the Employers’ Association, which reportedly met with the Draymen specifically on this issue (The San Francisco Examiner July 21, 1901: 18). Within a few days almost 1,000 Teamster’s Union men had been dismissed from their jobs, locked out because they refused to handle the “hot cargo” (The San Francisco Examiner July 23, 1901:1).

During the first few days, the Teamsters’ played a waiting game to see how things would develop and to put the responsibility for a wider strike upon the shoulders of the employers, while beginning notifications and discussions with their allies in the City Front Federation. Jefferson D. Pierce, Pacific Coast organizer for the American Federation of Labor, visited Teamster headquarters and, after appraising the situation, telegraphed President Samuel Gompers about the lockout. Meetings were held with the Sailors Union of the Pacific and representatives of the City Front Federation, but no decisions were made. Union pickets were sent to various key locations to watch and intercept any non-union drivers, explain the situation to them, and try to influence them to join the union. This tactic was successful in at least one instance when non-union drivers, reportedly imported from Benicia, gave in and returned their teams to the stables (The San Francisco Examiner July 22, 1901:2, July 23, 1901:2).

At this point in the developing situation, the Coast Seamen’s Journal, the organ of the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific, published a powerful editorial in support of the teamsters, warning the entire labor community of the likely result of the actions of the employers. The editorial began by pointing out:

...There was but one thing left for the Teamsters to do, and that they promptly did; they refused to do the work of the non-union concern. At this juncture the Employers’ Association showed its hand in the matter. The Draymen’s Association, against its will, as it appears, had been forced into the secret order of industrial assassins, and acting upon the mandate of that body the Draymen notified their employees that they must either “quit the union or quit their jobs.” This was a deliberate challenge of the Teamsters’ right to maintain their organization; it was a challenge dictated in the spirit that has all along characterized the Employers’ Association and its predecessors--the spirit of war and destruction to trade-unionism...Should the trouble spread, as it undoubtedly will if the Employers’ Association has its will...the result to this city and port may be better imagined than described. The Brotherhood of Teamsters may be depended upon to make the fight interesting for its opponents. Behind the Teamsters stand a large number of fellow trade-unionists who may also be depended upon to make a good run. It looks as though the crucial point in the conflict between the Employers’ Association and Organized Labor has been reached. There is but one way that we can see at present in which an upshot of far-reaching effect upon the city can be forestalled, and that is by a counter organization, tacit or formal, of press and public to offset the inequitable and desperate policy of the Employers’ Association. The only question at issue is as to whether or not men have the right to organize for their own protection and to hold their employers to the agreement made with them. The press and public can settle this question quickly and effectually. Unless they do, they will be responsible for whatever may happen as a consequence of leaving it to settlement by physical demonstration (Coast Seaman’s Journal July 24, 1901:6).

Police and City Government Side with the Employers

Late July saw a new development, the decisive intervention of Mayor James Phelan’s administration on the side of capital by detailing large numbers of police to help strikebreaking scabs destroy the union. Already by late July of 1901 over one half of the city’s police force, 300 out of 588 men, was detailed to protect the strikebreakers (The San Francisco Examiner July 27, 1901:3; September 26, 1901:12). This was initially done at the behest of the Draymen and not due to any need to protect law and order. On July 24 George Renner, the Manager of the Draymen’s Association, was quoted in The San Francisco Examiner: “...We have had mounted police and patrolmen detailed to accompany the teamsters who are at work, not because of any overt act, but because prevention is better than cure. It will take some time...to fill the places of all of the men who have refused to obey orders; but it will be accomplished in time...” (The San Francisco Examiner July 24, 1901:4).

City police were stationed on wagons (called “trucks”), driven by scabs, to act as guides and even drivers for those strikebreakers who did not know the city and to try to prevent union pickets from convincing them to join the union. Police not only acted as escorts for scabs, they even sometimes even called for them in the morning at their homes and accompanied them home at night (The San Francisco Examiner July 28, 1901:19). This almost immediately led to conflict, with police squads attacking and beating union men in union dominated neighborhoods in the south of Market area, which led to retaliatory violence against the strikebreakers by angry members of the local working class community. The San Francisco Examiner vividly described several incidents on July 25:

In the morning at 8 o’clock three non-union drivers were leaving C. B. Rode & Co.’s barn on Bryant Street, near Fifth, with trucks and the police requested the union pickets to leave the teamsters alone. The pickets argued the matter and in the meantime a crowd of union sympathizers, numbering about 300, collected. The manager of Rode & Co. telephoned to police headquarters and Captain Wittman, with a score of policemen, hurried to the scene. Wittman ordered his men to charge the crowd with clubs. The union men say the crowd was orderly and that the pickets were conducting themselves within the law. Four or five men were badly clubbed by Wittman and his squad. The crowd quickly dispersed. One of the drivers decided to join the union; the other two drove on with policemen on the trucks to protect them while going for loads. In the afternoon about 4 o’clock the union sympathizers gathered in large numbers at Sixth and Folsom streets. A truck owned by McNab & Smith came along Sixth street...The crowd closing around truck forced the horses...into the depression on one side of the street...The crowd hooted and tried to persuade the driver to leave his seat. Some one threw a stone, which hit him on the back of the head. That decided him and he made a break through the crowd to get away...Two more teams, belonging to the same firm, came along and the crowd speedily persuaded their drivers to join the strike...a policeman drove the dray down to the depot...The crowd soon gathered again and Sergeant Campbell and eighteen men were sent to disperse the gathering, which they did with some display of force (The San Francisco Examiner July 25, 1901:3).

These events apparently led Teamsters’ Union leaders Michael Casey and John McLaughlin to call out on strike almost all of the remaining union teamsters. By the next morning a total of 1500 men were locked out and on strike (The San Francisco Examiner July 25, 1901: 3).

With even more angry teamsters on strike, the confrontations between the local community of unionists and their supporters and scabs imported by employers from as far away as Bakersfield and Los Angeles quickly grew larger and more threatening. Police, who actively supported the bosses by protecting scabs, also were even more involved. The San Francisco Examiner reported on July 26:

About 6 o’clock last night a crowd of union sympathizers attacked a non-union driver on one of McNab & Smith’s trucks at Bryant and Third streets. There were about thirty boys and a number of men, Policeman Porter was on the truck. Rocks were thrown and an effort was made to pull the non-union driver from his seat. A crowd quickly collected and in a couple of minutes there were fully 500 people about the truck

...Policeman Porter drew his club, but he could do little with it, because the crowd closed in on him. Policemen Harrison, Eastman and half a dozen others from the Southern station who were in the district, learned of the trouble and charged on the crowd with clubs. The crowd kept increasing until there were more than 1,000 people on the street. Rocks and other missiles were hurled at the truck. Policeman Porter was struck on the left leg and injured. A rock also struck Policeman Harrison. The patrolmen cracked a number of the more aggressive men with their clubs.

As fast as the policemen cleared a way more men closed in on them. Fully twenty men were struck with the clubs of the officers before the truck was again started for the stables.

The crowd followed at a distance and continued to hurl stones at the policemen and the non-union driver finally got his load to the barn at Eighth and Brannan street. Policeman Porter will be incapacitated for duty by reason of the injury to his leg...

In the same neighborhood one of the trucks of McNab and Smith that are used to carry fruit for the California Cannery Company was disabled. A nut had been removed from one of the front wheels, and, without any warning, it came off, scattering fruit all over the street. Cannery hands were called out to carry the fruit into the sheds. The crowd became large and troublesome and began hooting the cannery employees. Sergeant Christensen, assisted by Policemen Hook and Burdette, charged the onlookers, who soon dispersed (The San Franicsco Examiner July 26, 1901:3).

More incidents illustrating that a community rebellion against the injustice of scabs and police trying to destroy the Teamsters union was underway followed on the next day:

Thomas Bryan, a Petaluma teamster, hired...by McNab & Smith, was seriously injured while on his way to supper by strike sympathizers on Thursday night. Bryan had both arms broken and was otherwise hurt...Policemen Peshon and P.L. Smith drew their revolvers and dispersed a crowd of men at Second and Folsom streets who had attacked the driver of a team...In a clash which occurred between the police and a crowd at Sixth and Folsom, John Ely, a teamster...received a severe laceration of the scalp from a club in the hands of Policeman Max Fenner...In a disturbance which occurred at Fifth and Bryant streets last evening, Adolph Thiler, a cabinetmaker...was badly beaten by Policeman Peter J. Burdette...Over 300 policemen are at present engaged in protecting the interests of the draying firms against their striking employees. All available men have been called to do actual police duty and are detailed either as convoys to trucks and teams or are patrolling the districts where trouble is most likely to arise...(The San Francisco Examiner July 27, 1901:3).

The Employers’ Association’s Ultimatum

The situation was still developing at the end of July when the Employers’ Association pressured various San Francisco capitalists to force their workers to choose between their union or their jobs. As The San Francisco Examiner (July 28, 1901:19) reported:

In many business houses yesterday the proprietors summoned their employees and put the question squarely to each one: “Will you take orders from us, or from your union?” On the answer hung the option of further employment. Those who elected to stand by their labor organization were “given their time” -- that is to say, were paid off and dismissed. Those who chose to remain at work were required to write out their resignations from the union.

The workers at the various San Francisco beer bottling establishments were presented with this ultimatum, as were workers at local box manufacturing factories and many members of the porters and packers union. Most of the affected workers stayed with the union and went on strike. It was clear to all that the Employers’ Association was behind this demand:

Inquiry among the employers at the different beer-bottling establishments led conclusively to the decision that their action had been prompted by the Employers’ Association and foreshadowed the steps taken by other employers yesterday in asking men to choose between their labor organizations and their employment...The employers made no secret of the fact that their action was concerted and the result of an understanding had in the Employers’ Association... (The San Francisco Examiner July 28, 1901:19).

San Francisco and Bay Area Unions Prepare to Fight

With the situation reaching a crisis point, the San Francisco Labor Council gave its executive committee power to take any necessary defensive or offensive steps against the “arbitrary action of the Employers’ Association.” It also adopted a resolution which read in part as:

Whereas, Organized labor of San Francisco and vicinity now finds itself menaced from every quarter by a secret body known as the Employers’ Association, with the purpose of destroying the trades unions, thus denying the members thereof the right to combine for their own protection...and

Whereas, The trades unions have now and at all times in the past executed every possible means to insure amicable relations between employer and employee, and in event of dispute to bring about a restoration of harmony by conference, conciliation and concession, and

Whereas, The Employers’ Association has persistently rejected these steps and now seems determined to pursue its policy of strife and destruction...and

Whereas, The dangerous and unlawful motives of the Employers’ Association are proved by its actions in forcing, by threats of retaliation and ruin, employers who are well disposed toward their employees...

Resolved, That, until said Employers’ Association makes formal declaration of its purposes and official personnel, it shall be regarded as having no legal right to exist and as having no claim to recognition...

Resolved, That the San Francisco Labor Council pledges itself, and urges a like declaration by each of its constituent bodies, to stand firm to the principles upon which we are organized, the first of which is the right of the workers in all callings to combine for mutual help as individuals and as organizations...

Resolved, That we reaffirm our position as favoring the adjustment of all existing and future disputes by means of conference between the parties involved...failing acquiescence in this proposal by the employers concerned, the responsibility for the continuance or expansion of the present strikes, lockouts and boycotts must be laid upon that party which has proved itself unapproachable to reason and… to the appeals of common humanity (The San Francisco Examiner July 27, 1901:3).

Final Attempts to Conciliate Fail

True to their principles and word, the highest level representatives of San Francisco’s organized working class--the Labor Council, the City Front Federation, and the Teamsters--were ready to meet and discuss the adjustment of any and all disputes with all appropriate parties. On the afternoon of July 29, even in the face of the blatant and continuous police aid given to the employers, they conferred with Mayor Phelan, the Municipal League’s “Conciliation Committee”, and some business representatives at the Mayor’s office to try to reach a compromise. True to form, the Employers’ Association refused to attend and meet with labor; the Mayor had to take labor’s proposals to the headquarters of the Employers’ Association in the Mills Building. After meeting with the leaders of the Employers’ Association, the Mayor came away without an agreement even to start negotiations, only a response in the form of a letter from M. F. Michael, the Associations’ attorney. The essence of this letter reprinted in full in the Examiner, was contained in the following paragraph:

I am instructed by the Executive Committee of the Employers’ Association to advise you that the proposition thus submitted appears to the association not to present a satisfactory solution of the present difficulties; furthermore, that the association is of the opinion that an agreement in the shape proposed could not be adequately maintained or enforced (The Examiner July 30, 1901: 2).

It was clear that the organized employers wanted total power over the workers. The exercise of such power was a main cause of the alienation that the workers had felt and were rebelling against. Collective power in a union gave the workers a feeling of wholeness and freedom they could gain no other way. As Sailors’ Union of the Pacific’s leader Andrew Furuseth commented to the press after the meeting:

It is not the unions that are bringing this upon the city. The employers ignore us entirely...they will not recognize our committees or delegates or agents. They are willing to give the individual employment, but they are determined to crush the unions. They had no representatives at this afternoon’s meeting in the Mayor’s office, and of course there could be no results (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1).

The lines were now drawn in the sand; it was up to working people and their leaders to act.

July 30, 1901: General Strike on the Waterfront

Immediately following the conciliation talks, the leaders of the City Front Federation called a meeting for that same evening, July 29. All the issues involved were carefully and thoroughly discussed, and it was not until about midnight that the following decision in favor of a general strike of all member unions was made:

Resolved, That the full membership of the City Front Federation refuses to work on the docks of San Francisco, Oakland, Port Costa and Mission Rock and in the city of San Francisco, but that the steamships Bonita and Walla Walla, which sail tomorrow morning, and which have booked passengers, be allowed to go to sea with the union men of their crews (The San Francisco Examiner July 30, 1901:1).

While the leaders were deliberating, mass gatherings of rank and file members were organized all over San Francisco, and, as the night wore on, these union members were anxious for news. About 600 members of the Brotherhood of Teamsters were assembled at the hall of the San Francisco Athletic Club at the corner of Sixth and Shipley streets. When Michael Casey arrived after midnight and announced that the City Front Federation was calling a general strike on the waterfront :

... a scene of the wildest enthusiasm ensued. Cheer after cheer was given. Since the inception of the strike the teamsters have been compelled to fight the merchants and bosses single-handed, and it was generally admitted that the strikers would be ignominiously defeated unless other unions rendered immediate assistance. Thus the men had come to look on the City Front Federation, embracing the strongest combination of united labor on the Pacific Coast, as their most desirable ally.

After Business Manager Casey announced the decision of the City Front Federation, the Brotherhood of Teamsters decided by a unanimous vote to fight the strike out to the bitter end without regard to the cost or consequences. The brotherhood has in all almost 2000 men now on strike (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1).

The scene at California Hall, where the members of the Porters, Packers and Warehousemen waited for word, was no less dramatic. The 2000 members of this union were

...unanimous in wishing that a general strike would be ordered and could not understand why the men of the city front could not come to the same conclusion without the necessity of a lengthy session...The guard at the door of the union’s meeting place was the first man to receive the news. When he opened the door and announced to the anxiously waiting laboring men that their wishes had been granted and that on the morrow 16,000 men would quit work and enter the ranks of the strikers and the locked out men the cheers were deafening. The men yelled themselves hoarse, for the announcement of the general strike meant that their fight was to be made the fight of every laboring man in this city (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:7).

Similar “tumultuous cheering” took place once the decision to strike was announced at the mass meetings of the Sailors’, the four Longshoremen’s locals and other interested unions (Coast Seamen’s Journal July 31, 1901:11). Speaking before hundreds of sailors at their headquarters, Andrew Furuseth said that the “employers are determined to wipe out labor unions one after another...There is no other way of having peace except by fighting for it” (Knight 1960:77). The organized workers of San Francisco were practically unanimous on the need for a general strike on the waterfront to counter the attempt to crush their unions (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1).

There were ten striking unions with an approximate membership of 16,000 men.

| Union | Number of Members |

| Sailors’ Union of the Pacific | 4,500 |

| International Longshoremen’s Association (four branches) | 4,500 |

| Brotherhood of Teamsters | 2,000 |

| Porters, Packers and Warehousemen | 2,000 |

| Pacific Coast Marine Firemen | 1,500 |

| Marine Cooks and Stewards | 700 |

| Piledrivers and Bridge Builders | 300 |

| Ship and Steamboat Joiners | 300 |

| Coal Cart Teamsters | 200 |

| Hoisting Engineers | 75 |

| TOTAL | 16,075 |

On July 30, these unions, organized as the City Front Federation, issued a statement on the causes of the strike, asserting the rights of the working class against “arrogant capital”:

Having closely watched the trend of affairs throughout the country and being cognizant of the policy of the employers, which is to disrupt labor organizations...the Federation claims the right for its members to organize for their mutual benefit and improvement... we further claim the right to say how much our labor is worth and the conditions under which we will work. The Employers’ Association, composed of the principal importing and jobbing concerns of this city...have tried with more or less success to destroy some of the smaller organizations, and as their minor successes gave them confidence they reached out further with the idea that ultimately their plan would be successful...In view of the fact that the teamsters were locked out the Federation found it absolutely necessary to take action...The Federation has exhausted all honorable means to have the difficulty adjusted...and finds that there is nothing left but to appeal to its membership to be true to the cause for which organized labor stands...we are satisfied that we have done everything we could to avert this crisis, but arrogant and designing capital willed it otherwise. Those individuals in society who would use their industrial power to rob us of our right of organization...must bear the responsibility for whatever may now take place (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1). The strike’s aim was to economically punish the employers in order to put irresistible pressure on the Employers’ Association to agree to negotiate a fair settlement which preserved and enhanced union power. Andrew Furuseth, secretary of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, was elected chairman of the strike committee. He said at the outset that: “We have dallied long enough with the Employers’ Association... our action will teach them that we mean business. Every man is determined and the sooner the association appreciates this the better it will be for them and the business interests of this city and vicinity. All the talk has been done -- this is action” (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:7).

The all-out battle for the union rights of working people and against the Employers’ Association was underway.

The Strike Leaders: Furuseth and Casey