Women's Liberation Origins and Development of the Movement

Historical Essay

by Joanna Dyl

Women protest Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, NJ in 1968

In 1968, as women's liberation groups were springing up across the country, Mimi Feingold founded San Francisco's first small group by gathering some women with connections to the antiwar organization the Resistance. In the Bay Area, as in the rest of the country, the founders of women's liberation were veteran activists from the civil rights movement and the New Left of the early 1960s. Feingold herself had participated in the Freedom Rides, the Congress for Racial Equality, and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), as well as the draft resistance movement.(1)

Pam Allen, who became nationally known as the author of a pamphlet on consciousness-raising, joined this original group at its second meeting in September of 1968 she had just moved to San Francisco from New York, where she had been a founder and active member of the group New York Radical Women. She too had a history of involvement in the civil rights movement, with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). She "brought to the group a political commitment to building a mass women's movement."(2) In total, five of the original members of this first San Francisco group had been involved in the civil rights movement in the South.(3) This group named itself Sudsofloppen.

Sudsofloppen members possessed a radical left perspective on society. At the same time, however, their experiences in the male-dominated movements of the left had also given them a distrust of traditional forms of organizing. Allen wrote that, "Because many of us were ex-'movement' people we had tremendous hostility toward the concept of organizing women. . . . We were all well schooled in the inhumanity of the left movements, in their disregard for the needs of individuals."(4)

Such contradictions were felt by radical women across the country. Although women had been involved in the political movements of the 1960s from the beginning, their experiences had not been entirely positive. Young women had gained increased independence, organizing skills, and a radical understanding of society. But their treatment by radical men -- both in movement groups and in personal relationships -- contradicted their expectations of community and democracy in the movement and provided the impetus for women to begin to organize their own movement.(5) The skills and networks with which they built the women's liberation movement were grounded in their political history on the left. Women's styles of organizing also responded to the oppression they had experienced in male-dominated movements by emphasizing egalitarian relationships and personal development.

The women of Sudsofloppen's "driving need to extend our contact to other women who were thinking as we were" led them to call for a conference of women involved in women's liberation in the Bay Area, which took place in January, 1969.(6) A second conference occurred in March, and these gatherings continued on a semi-regular basis throughout the year. The year 1969 also saw a wide range of women's liberation actions and activities in San Francisco. For example, on February 14, women in San Francisco staged a demonstration at the Bridal Fair exposition there, in conjunction with a similar protest in New York. They used tactics ranging from picketing and guerrilla theater to leafleting.(7) In December, activists staged a teach-in on the oppression of women at San Francisco State.

At the end of 1969, the participants in women's liberation in San Francisco defined their movement as: A women's organization which grew out of the radical student movement. . . . One year old in San Francisco. Predominantly young, white and middle class. An organization of the isolated and alienated women of the movement who rebelled against the stereotyped role they were expected to play. Many women's liberation groups throughout the area. Concentrate on small group involvement of women. . . .(8)

Women's liberation was identified as an "organization" rather than a movement, but this "organization" consisted of many small groups instead of a single unified structure, although the choice of terminology may also have reflected the beginnings of the city-wide umbrella organization known as San Francisco Women's Liberation (SFWL). By 1970, there were an estimated sixty-four small groups in the Bay Area.(9)

On May 16 and 17 of that year, members of women's liberation in San Francisco came together for a "mass meeting" lasting a total of twelve and a half hours. The diversity of groups present was remarkable. Sixteen "small groups" (meaning primarily consciousness-raising groups) were represented, including Sudsofloppen, and eighteen action groups were present. Attendees included the consciousness-raising group Gallstones, the explicitly-leftist Young Socialist Alliance and Socialist Workshop, the SDS Women's Caucus, the Student Mobilization Caucus, Red Witch, and Gay Women's Liberation. More task-oriented groups included a Women's Center Committee, Small Group Workshop, Media Workshop, Free Women's Press, and Women's Street Theater. The result of this marathon meeting was a four-part organizational plan for SFWL. One step was the establishment of a newsletter -- the first issue was sent to 483 women and circulation increased to over 1200 by the end of 1970.

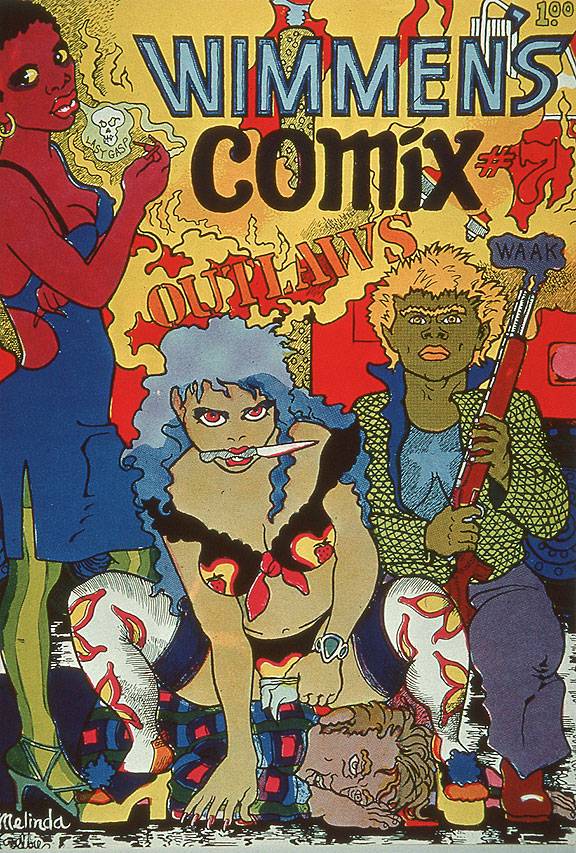

Wimmins Comix, a comic of the late 1970s, cover art by Melinda Gebbie.

SFWL remained essentially a coalition, with the real work of the movement being done in the action groups and consciousness-raising groups. This reliance on the small group persisted over time only with constant evaluation of its strengths and weaknesses. As early as October 1969, the Bay Area movement conceived the "group-in," which women attended with their small groups to talk about the small group as a movement organization. The series of group-ins held that year considered the needs filled by the small group, how political the small group is, and "is the small group a dead-end or is it a constantly growing organism?"(10) The question of the tactical relevance of the small group -- whether the collectivist small group could be an effective organization for achieving political and social change -- was an important issue in the local women's liberation movement. Many women concluded that being out "in the streets" is the male version of political action, but if the personal is political, the small group is a political structure by virtue of its bringing women together, in a setting separate from men, to talk about (and redefine) the political.

As women sought to expand their activities beyond consciousness-raising, the solution was not always to alter the role of the traditional small group. Instead, the women formed action and task-based collectives. Sudsofloppen wrote in 1969 that "we see the collective as an ideological base for action which would be planned in work projects, such as an abortion workshop."(11) These additional groups generally remained small and maintained the collectivist structure, but they moved away from the tactic of consciousness-raising and emphasized more tangible goals.

Instead of relying on large, centralized organizations, the women's liberation movement chose a structure consisting of a proliferation of small groups ranging from consciousness-raising groups to alternative press collectives, from action groups to alternative service providers, to meet the different tasks facing the movement. The women of the Bay Area feminist newspaper It Ain't Me, Babe asserted a vision of the women's liberation movement that declared their opposition to mass umbrella organizations: "We must keep in mind that we are a movement not an organization. Our movement can and will be composed of many action organizations differentiated by their political orientation -- rather than a single organization that attempts to represent everyone's politics."(12)

The women's liberation movement consisted of an eclectic mix of consciousness-raising groups, action organizations, and alternative institutions almost from its inception, and this diversity was itself a reflection of the movement's roots in the left and the counterculture. In fact, the greatest legacies of the women's liberation movement have been the success of consciousness-raising in transforming the expectations and lives of individual women and the development of a culture of feminist bookstores, women's studies programs, rape crisis centers, and similar institutions in San Francisco and across the country.

1. Sara Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), p. 204.

2. Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1989), pp. 73-74; Pamela Allen, Free Space: A Perspective on the Small Group in Women's Liberation (Albany, CA: Women's Liberation Basement Press, 1970), p. 1.

3. Pam Allen, personal interview by Deborah A. Gerson, June 16, 1994.

4. Allen, Free Space, p. 4.

5. Evans, Personal Politics.

6. Allen, Free Space, p. 8.

7. Judith Hole and Ellen Levine, Rebirth of Feminism (New York: Quadrangle, 1971), pp. 128-129, 410; Celestine Ware, Woman Power: The Movement for Women's Liberation (New York: Tower, 1970), p. 48.

8. SPAZM, December 18, 1969.

9. Deborah Goleman Wolf, The Lesbian Community (Berkeley: University of California, 1979), p. 66.

10. SPAZM, October 1, 1969.

11. SPAZM, December 7, 1969.

12. "The Women's Movement," It Ain't Me, Babe, March 15, 1970, p. 2.