Vietnam Day Committee

Historical Essay

By Lucy Tate

| In the late 1960’s, students at the Berkeley campus voiced their opposition to American aggression in Vietnam by forming the Vietnam Day Committee (VDC) with goals of organizing mass civil disobedience and directly disrupting the war effort. Initially organized as a committee to plan a one-day teach-in against the Vietnam War, the group developed into a lasting organization that significantly contributed to the building of the broader, international anti-war effort. |

Most of us grew up thinking that the United States was a great and humble nation, that only involved itself in the affairs of other countries reluctantly and as a last and final resort. But now the war in Vietnam has provided the incredibly sharp razor that has finally separated thousands and thousands of people from their illusions about the morality and integrity of this country's purposes internationally… What kind of a system is it that justifies the United States in seizing the destinies of other people and using them callously for our own ends? We must name that system and we must change it and control it, or else it will destroy us.

—Paul Potter, president of SDS, speaking at Vietnam Day 17 April 1965

Landscape of the 1960’s

Through their participation in the Civil Rights Movement and then the Free Speech Movement, students in the San Francisco Bay Area came into their own as agents of change in the politically tumultuous sixties. In the second half of the sixties, as students nationwide became increasingly disillusioned with the war in Vietnam, they sought ways to translate their sentiments into collective, organized, action. At UC Berkeley, the political activism of the era, combined with student aspirations to oppose the war, led to the emergence of new political organizations such as the Vietnam Day Committee (VDC).

While the Committee stood on its own, the organization was born out of the political climate produced by the Free Speech Movement (FSM) as “one of the fruits of the FSM’s victory.”[2] Another organization with a large presence on the Berkeley campus was Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Many flyers for events hosted by VDC describe a partnership of “co-organizing with Students for a Democratic Society,” however such collaborative efforts did not exclude the VDC from organizing independently of the SDS.[3] While SDS published the Port Huron Statement against the war in 1962 on the national stage, the local branch of SDS created an “Anti-Draft Resolution.”[4] Still, SDS was at heart a multi-issue organization, and “unwilling to wait for SDS to pick up the ball on Vietnam, but [assuming] it would promote actions in the U.S., activists looking to conduct immediate actions formed the VDC.[5]

Meet the VDC

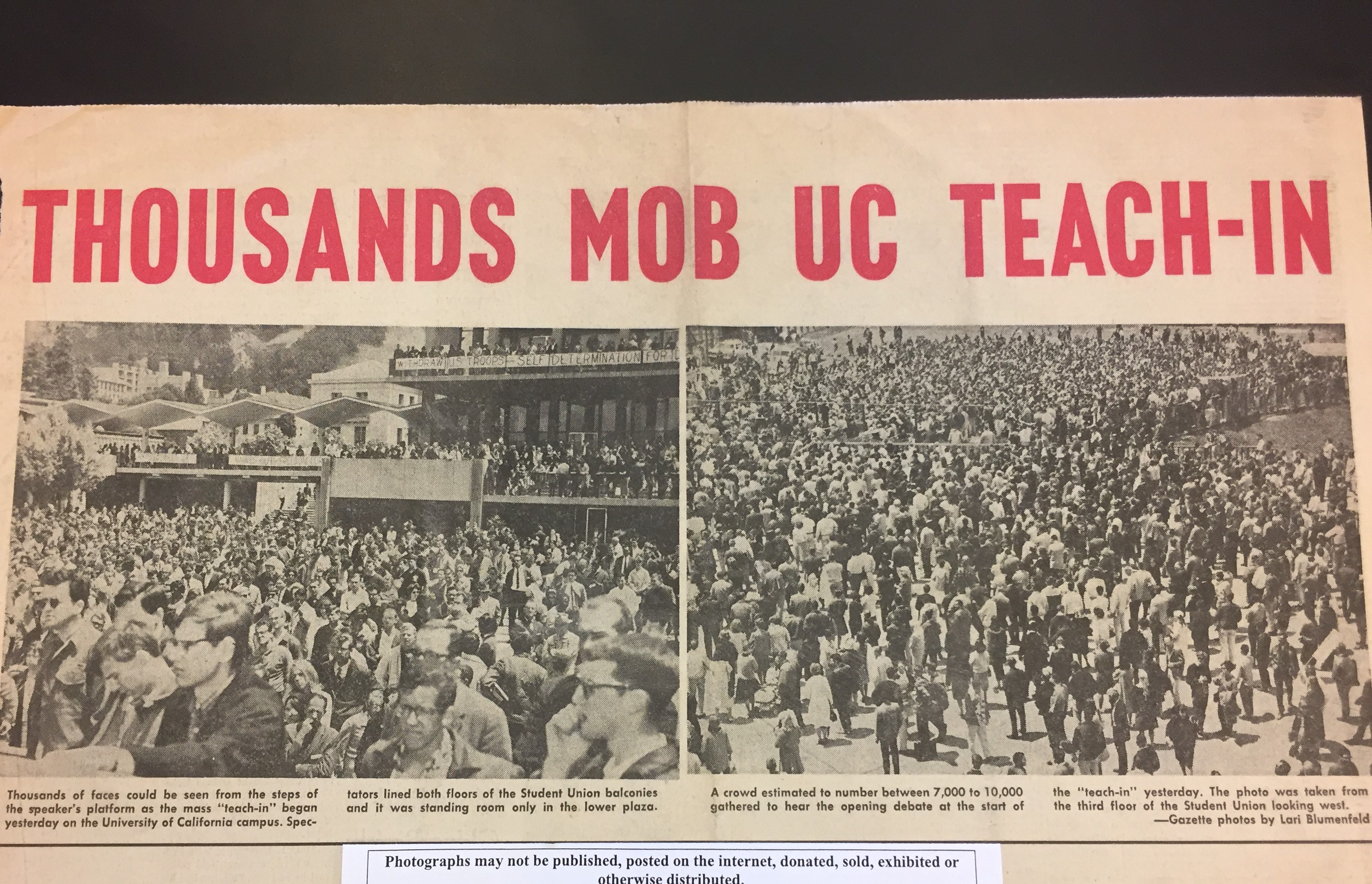

The VDC was born out of a 36-hour long teach-in called “Vietnam Day,” which featured famous speakers and activists, and attracted over 30,000 participants.[6] The organizers of the VDC include Jerry Rubin, Stephen Smale, Barbara Gullahorn, Paul Montauk, and a number of others. Rubin, a graduate student in the Sociology Department, and Smale, mathematician and professor, were highly influential among group members.

Members held weekly “discussions of tactics and their political implications” at the Vietnam Day Committee office at 2407 Fulton Street, Berkeley.[7] While no single, determinate set of politics grounded its organizing, the VDC did hold a set of principles highly influenced by the Free Speech Movement and the other civil rights movements occurring at the time, as their first statement of policy demonstrates:

The Vietnam Day Committee is a group of students, faculty and other members of the Bay Area community opposed to American intervention in Vietnam, the Dominican Republic and wherever else it may occur. Revolutionary struggles for self-determination are sweeping the world today. American suppression of these movements, we believe, is immoral, and a threat to the peace of the world. The Vietnam Day committee is organizing nonviolent direct actions, teach-in’s, door-to-door organizing and other educational activities to oppose American intervention. We believe that struggle for self- determination in other continent is related to the struggle for democracy in America — a democracy in which the people have the facts and the power to make decisions for themselves. The struggles in American against racism, poverty and bureaucratic conformity are part of the same movement as the struggle against American militarism.

We must build a New America, and join with those peoples in Asia, Africa and Latin America building a New World. Join the Vietnam Day Committee: only $0.25 makes you a card-carrying member!

—Vietnam Day Committee: statement of policy [8]

Aiming to tackle the war within the broader context of fighting “undemocratic power” and a “lack of representation,” the VDC envisioned the anti-war effort as another of many fronts in a unified, larger struggle.[9] A flier created by the VDC for a demonstration reads, “Vietnam, like Mississippi, it not an aberration—it is a mirror of America. Vietnam IS American foreign policy…. We must say to Johnson, if you want to go on killing Vietnamese, you must jail Americans.”[10]

Based off of these founding beliefs, the VDC utilized a multiplicity of tactics and means of engagement to achieve their aims. This included the serial distribution of anti-war literature — including a monthly newspaper, a bibliography of recommended reading material, and short cartoons and articles for troops overseas. The VDC also often spent time canvassing against the war, mainly in disenfranchised communities. [11] Most of all though, through their positionality as American students at an institution highly connected to the military, they sought to directly intervene in processes that enabled the continuance of American aggression abroad. In a most creative embodiment of such aims, some members tailed trucks transporting locally produced napalm in a pickup truck towing signage that read, “Danger, Napalm Bombs Ahead.”[12] However, the VDC would not limit itself to solely educational activism such as this, but would go on to implement mass civil disobedience tactics to advance their cause of immediate and complete withdrawal from Vietnam. In literature created by the VDC, the organization declares, “The primary strategy of the Vietnam Day Committee is primarily to mobilize as many of those people now opposed to Johnson as possible, rather than to attempt to rationally change the minds of those support Johnson, although of course we are trying that too.[13] Highly-coordinated, highly-publicized action will make people feel that they are not alone in speaking out.”[14]

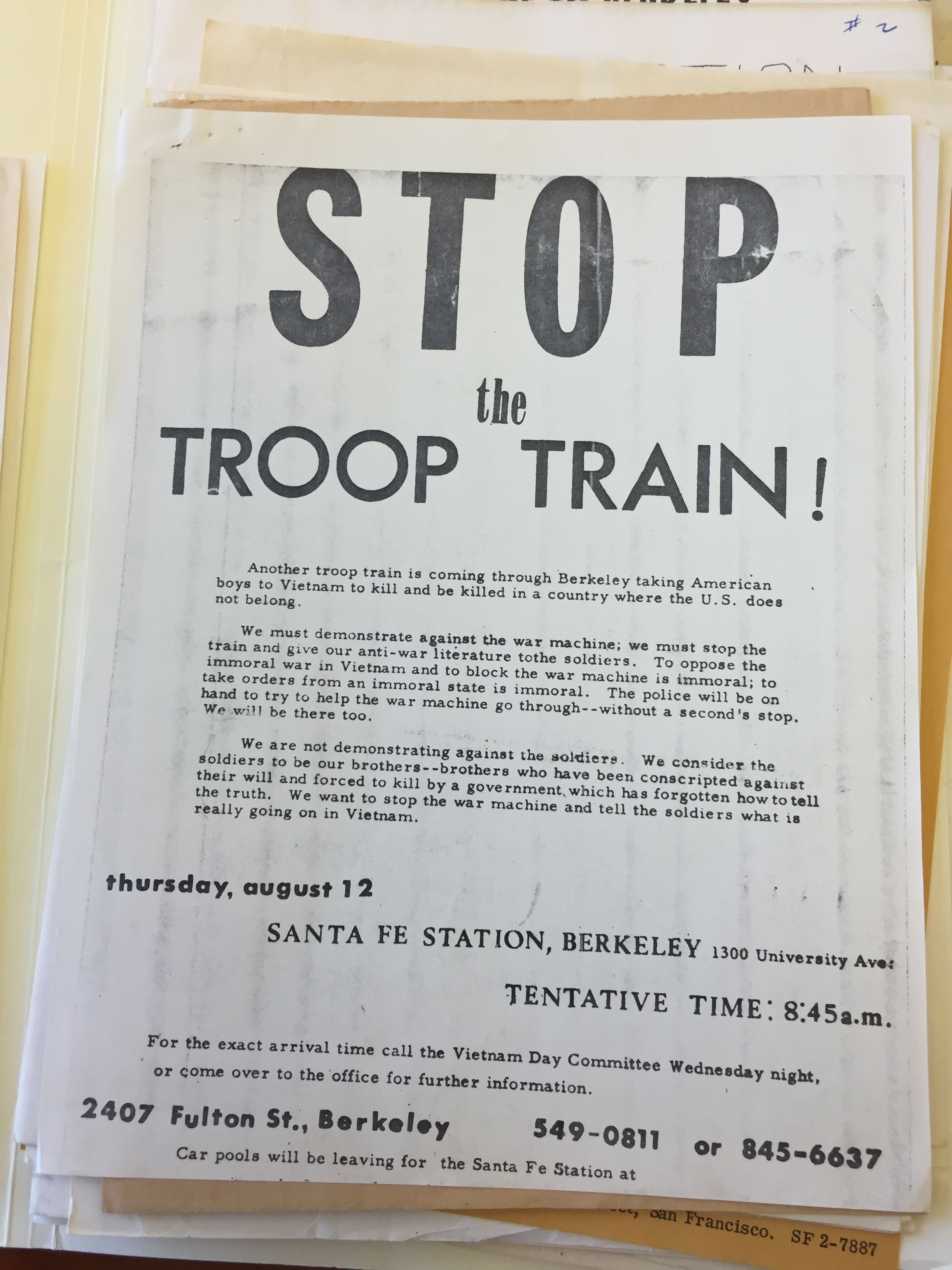

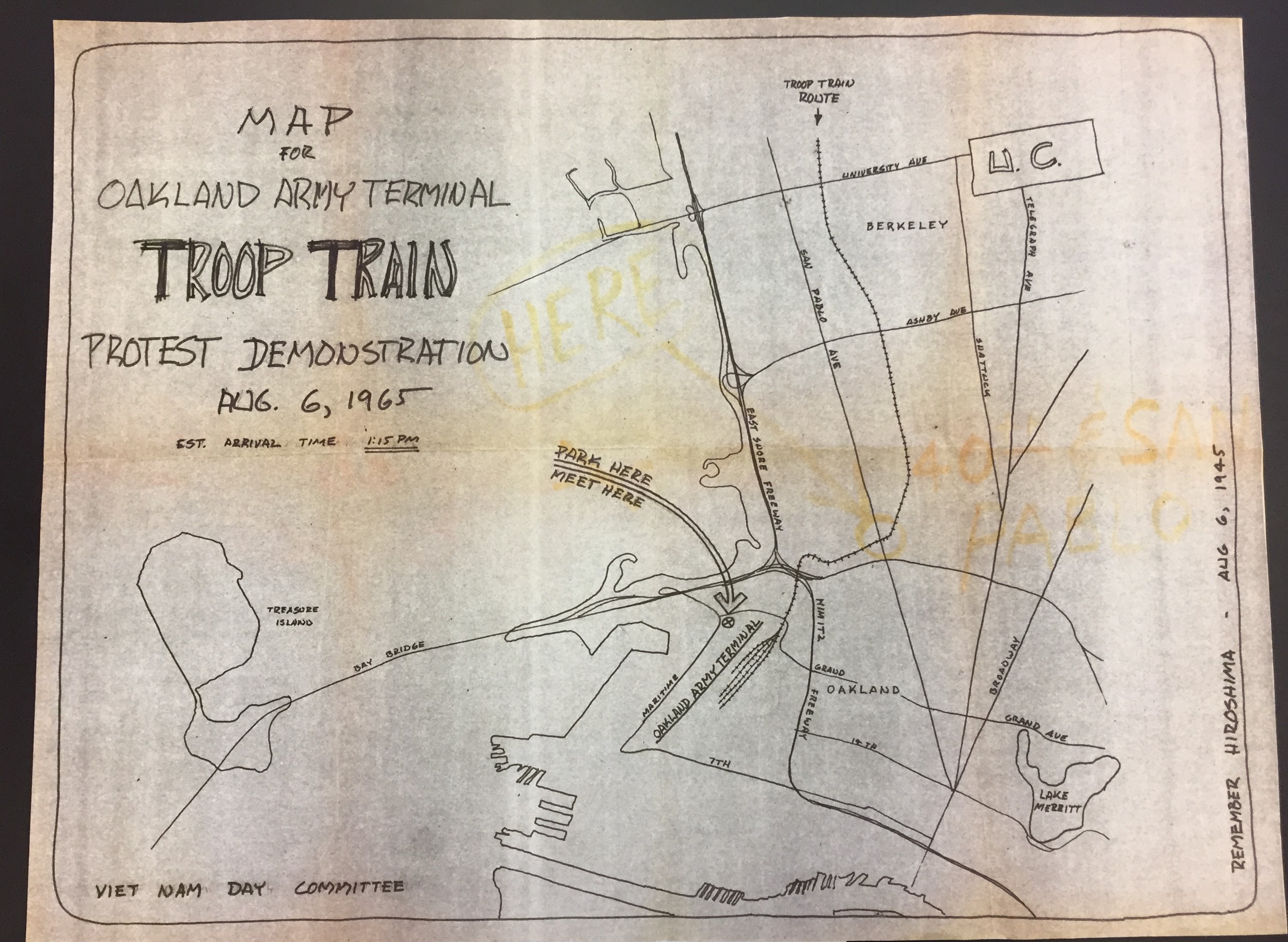

Troop Trains and Direct Action

As the war began to escalate rapidly, with about 20,000 soldiers sent to Vietnam every month, VDC stepped onto the stage. Many soldiers bound for Vietnam came through Berkeley and Oakland. A VDC newspaper articulated that “a troop train is not merely a train, it is a symbol; an extension of the war machine.”[15] In fliers calling for demonstrators to flock to the tracks, the VDC called for students and community members to “demonstrate against the war machine; [to] stop the train and give [their] anti-war literature to the soldiers.”[16]

The first of these demonstrations brought 150 people to the train tracks.[17] Some of these activists sat on the tracks to block trains carrying U.S. soldiers bound for Vietnam.[18] These trains did not stop or slow upon arriving before these youth however, and policemen in plain clothes often had to push activists off the tracks to prevent their otherwise imminent deaths. These actions immediately garnered national news coverage.[19] Although many soldiers did not react or seem sympathetic, a soldier in one car of a train was reported to have held up a sign to a window which read, “Keep it up. I don’t want to go.”[20] A total of four blockades took place in August.[21] The fourth included a thousand picketers. [22] “I loved that,” participant Marilyn Milligan said. “That seemed to be a clear expression of how I felt.”[23]

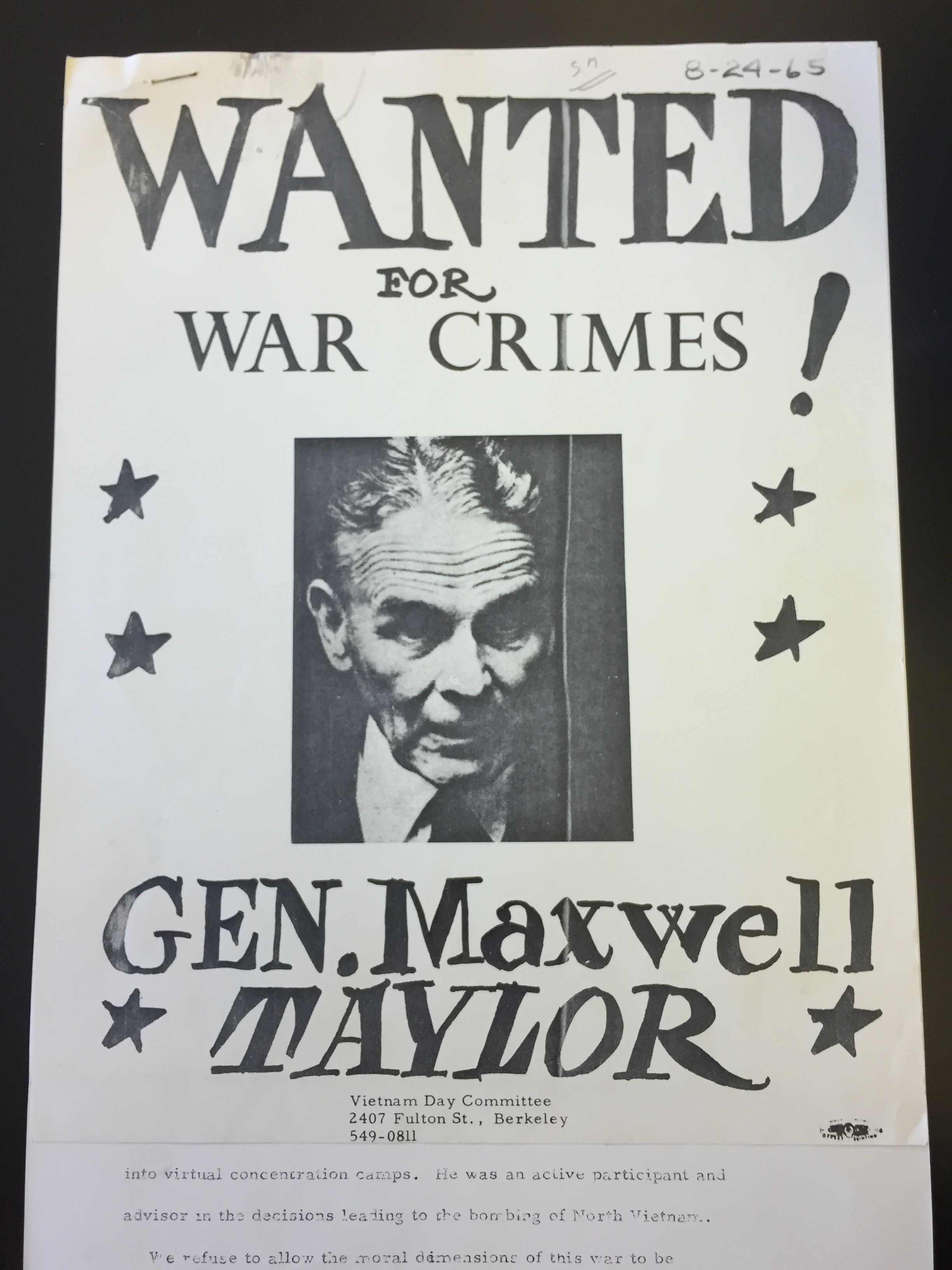

In another instance of direct action, the VDC organized a picket against General Maxwell Taylor. When Taylor arrived at San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel on August 24th, 1965, there were 100 VDC members awaiting his arrival.[24] Flyers depicting Taylor’s face and the declaration, “Wanted for War Crimes” were thrust at him and those who passed by.[25] Fleeing the commotion, the General was forced to take cover in the manager’s office.[26]

International Days of Protests, October 15-16th, 1965

The International Days of Protests rally was organized to manifest simultaneous antiwar protests overseas and within the U.S.[27] Rubin traveled to Washington to propose idea of “International Days of Protest” at the Assembly of Unrepresented People. According to the VDC, priorities for the peace movement included: national and international solidarity and coordination on action; militant action, including civil disobedience; extensive work in the community to develop off-campus grassroots opposition and to benefit from the militancy of direct action.[28] The state department, which originally intended to send a representative, withdrew from the program because it was “imbalanced.”[29] The National Guard of September 4, 1965 wrote, “Preparations are being made in about two dozen American cities for coordinated mass protests October 15-16th in opposition to U.S. aggression in Vietnam… in long-range benefit to the peace movement, for the emphasis of the ‘national days of protest’ is on community organization and education as well as on direct action against the war”.

The event attracted thousands of people in Berkeley.[30] Many students and professors took their first public steps against the war at the event’s workshops and teach-in’s. Media headlines regarding the protests also served to spread concern regarding U.S. foreign policy off of the campus as well.

Oakland Induction Center

As culmination of the International Days of Protests, the Vietnam Day Committee organized a seven-mile anti-war march to the Oakland Army terminal. The City of Oakland refused a permit for the demonstration, but the VDC voted to march anyways.[31] A member of the Committee said, “The Berkeley-San Francisco Bay Area aspect of the international protest will center around the ‘pacification’ of the Oakland Army Terminal.”[32] Flyers put out for the event by the VDC read, “We will tell them that under the 1949 London Treaty and The Nuremberg Codes they bear individual responsibility for committing war crimes, even if they are following the orders of a superior or obeying national law.”[33]

That night, police blocked people from approaching the terminal, and marchers were headed straight towards a collision with officers should they continue en route. Leading members of the march made the decision to turn the march around, not wanting to risk an unnecessary confrontation with the police. Jack Weinberg, a member of the Committee said, “I just decided that we were turning. I basically was the person who made that decision, but for years afterwards, got great degrees of shit for it, never knew if I did right or wrong. I still don't know if it was right or wrong decision.”[34]

The next day an even larger march that attempted to cross into Oakland found itself facing a police presence again. But this time, the marchers found themselves facing opposition from the Hells Angels as well. Breaking out into a scene of violent confrontation, members of the VDC described the event as a riot in which, “scenes of thousands of middle-class youth being carried away by military police [was] in every American living room… Massive disobedience on Vietnam [would] dramatize the issue throughout the country, express [their] personal rejection of the war machine, and expose the inability of traditional American institutions to cope with dissent.”

The End of The VDC, and Its Lasting Impact

The Vietnam Day Committee began to spread itself thin and lost a lot of momentum after the International Days of Protest. It even failed at pursuing electoral politics through Robert Scheer, a local antiwar activist and scholar. Organizers faced Scheer’s defeat as a final nail in the coffin, among other gradual VDC failures. VDC headquarters were bombed in April 1966 and a few months later UC Berkeley had banned the Committee from campus, on the grounds that many of its members were not students. While the VDC would continue to be active into the early 1970s, after the peak of activity in 1965-1966, the VDC began winding down.

However, while active, the Vietnam Day Committee succeeded in many ways, attracting thousands of people to its demonstrations between 1965 and 1966, and articulating antiwar perspectives that became immensely popular as America aggression escalated in Vietnam. These perspectives had previously garnered limited public support by “radicals” on or nearby the Berkeley campus. Prior to the mass activism of anti-war movements like the VDC, many Americans simply did not know enough about the war to take a strong stance. Student activists, such as those involved with the VDC, helped break this silence with their efforts aimed directly at the soldiers leaving from locations like the Oakland Army Base. “Now we have to continue to change this country,” said, Nancy Kurshan, an organizer with the Vietnam Day Committee— for activists such as Kurshan, the end of the war did not mean the end of the struggle. [35]

Notes

[1] Mark Kitchell, Berkeley in the 60s (New York, 1990)

[2] Vietnam Day Committee, We Accuse: A Powerful Statement of the New Political Anger in America, as Revealed in the Speeches Given at the 36-Hour ‘Vietnam Day’ Protest in Berkeley California (Berkeley: Diablo, 1965), 2.

[3]Rubin, Smale, Gullahorn

[4] flyer, Stephen Smale papers, 1950-1998, MSS 99/373, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[5]Tom Gitlin, The War Within: America’s Battle Over Vietnam (Berkeley, 1994), 51.

[6]Ibid, 24.

[7]Seth Rosenfeld, Subversives: The FBI's War on Student Radicals, and Reagan's Rise to Power (2012).

[8] flyer, Stephen Smale papers, 1950-1998, MSS 99/373, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[9]flyer, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU-495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[10]Vietnam Day Committee Newspaper, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU- 495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[11] Gitlin, 50.

[12]Ibid, 50.

[13] flyer, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU-495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Vietnam Day Committee Newspaper, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU- 495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[16] flyer, Stephen Smale papers, 1950-1998, MSS 99/373, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[17] Vietnam Day Committee Newspaper, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU- 495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[18] Gitlin, 50.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Vietnam Day Committee Newspaper, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU- 495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[21] Tom Gitlin, 50.

[22] Vietnam Day Committee Newspaper, Clark Kerr office files regarding the Free Speech Movement, CU- 495, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[23] Gitlin, 50.

[24] Steven Smale: The Mathematician Who Broke the Dimension Barrier.

[25] Gitlin, 50.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Gitlin, 51.

[28] flyer, Stephen Smale papers, 1950-1998, MSS 99/373, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[29] flyer, Stephen Smale papers, 1950-1998, MSS 99/373, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[30] Gitlin, 50.

[31] Mark Kitchell, Berkeley in the 60’s (New York, 1990).

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Steve Long May, The Barb (Berkeley, 1975), 11.