Twentieth Century Indigenous San Francisco

Historical Essay

by Cybele Zhang, 2019

Klamath River Hurok Chief Tim Williams addresses a crowd prior to the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969. The reclaiming of the island was integral in broadcasting the Red Power Movement to the nation from its epicenter in San Francisco.

Photo: National Library of Medicine—National Institutes of Health

| The 1950’s and 60’s saw a notable demographic shift in San Francisco as urban Native American populations swelled. Hippies enthusiastically accepted what they perceived as Native community values, religion, art, etc., and “Indian” culture became deeply intertwined in counterculture aesthetics. This appropriation was extremely problematic, however, as the hippie’s fetishization of all things “Indian” grew farther and farther away from the real tribes and the injustices they suffered. In order to fight back against this loss of culture, the Red Power movement grew nationally and climaxed in San Franciscan activism and the reclaiming of Alcatraz. |

On August 1, 1953, the federal government passed the House Concurrent Resolution 108, which was intended to eradicate poverty and harsh living conditions on Native American reservations through citizenship and assimilation, but the resolution instead resulted in loss of culture and the displacement of Native people. (1) The legislation gave each tribe the power to vote whether or not to “terminate” their federal status, but misinformation and enticements of extensive federal investment from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) lured 109 tribes — none of which had any legal representation — to give up sovereignty, native-owned land, and federal protections for promises that the BIA rarely fulfilled. (2)

Now without a home and thrown into the minefield of American law, indigenous people struggled to maintain their former way of life. (3) Jobs were scarce and the annual income of an indigenous man was less than a fifth of the national average.(4) Instead of placing resources into sustaining growth in Native communities, the BIA instead presented the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 — forcing over 100,000 Natives to find a new, urban life.(5) This gave rise to a phenomenon that the Oakland Museum dubs “Urban Indians.” (2) The act encouraged Native Americans to settle in one of ten designated cities, where tribes from across the nation would assimilate. Four of the relocation centers were in California: Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland. Los Angeles and San Francisco were designated as vocational training centers, where indigenous people were encouraged to move in order to learn a trade. Many who moved intended to sojourn, learn a skill, and return home. But the government did little to facilitate the transition, and this idealized plan fell apart for many. (6) Once in San Francisco, many Native people had trouble adjusting to foreign, urban life and never completed their vocational programs. (7)

Urban Indians

The act caused a notable demographic shift in SF, and the Native population in the city tripled in a single decade. In 1950, only 331 Native Americans lived in the city, but by 1960 the population was 1,068 — accounting for 0.1 percent of the total population. By 1970, that number was up to 2,900 — 0.4 percent of the total population.(4) These new San Francisco communities were multi-tribal, often including multiple relocated families from various parts of the country, so connections to specific tribes weakened over time.(8) Without land of their own, many indigenous people settled in poorer neighborhoods of the city, including in the Tenderloin and the Mission District — which subsequently became dubbed “Red Ghettos.”(9) Now without traditional spaces, many ceremonies, hunting and gathering rituals, and religious practices tied to the land were lost. Furthermore, indigenous languages began to die out in the Native Americans’ attempt to assimilate. (10)

Isolated from their tribal communities, Native Americans routinely faced racially based police brutality and still are one of the most disproportionately represented groups in prison.(9) Like other racial minorities in San Francisco, American Indians faced prejudices in hiring, leading to disproportionately high unemployment and homelessness rates — furthering a cycle of poverty.(11) Now urbanized and terminated, Native Americans were without the federal resources they previously had; one of the most catastrophic rights lost was healthcare. At the time, Indian Health Services could not be found outside a reservation, so most indigenous people were left with no coverage.(9) Chah-tah Gould notes that many Native people, faced with these growing challenges and with few places to seek help, turned to gang membership and struggled with alcoholism and depression.(11)

Additionally, countless social divisions kept Native people from ever fully integrating into dominant white society. Segregated housing manifested in segregated schools, businesses, and social networks. Stereotypes of cowboys and savage Indians were still rampant in popular Western movies, and this messaging shaped the San Francisco zeitgeist around indigenous people.(12) Nevertheless, although “Indians” were outcasts in dominant society, the hippie counterculture was extraordinarily receptive to the city’s new inhabitants — but not always for the right reasons.

Native Turns Hip

For many San Francisco hippies, who were largely blind to the true challenges Native people faced, “Indians” were celebrated as the ultimate free spirits. The Oracle Editor-in-Chief Allen Cohen said, “the hippies…shared with the Indians a sense of cultural alienation from American society. There was a general perception that urban society was a cancer and a scourge upon the earth.”(13) Apache actress and activist Sacheen Littlefeather noted that it was popular amongst hippies to claim “my ancestor was a Cherokee princess” in attempt to claim a stake in the intrigue of Native American culture.(12) Similarly, Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo writes, “[Hippies] were into playing Indian…probably because the western warrior or renegade fantasy meshed so neatly with the bad-boy, counterculture rebel” (14). Dakota activist John Trudell said, “In a way [hippies] were trying to imitate us, but they were trying to remember who they were.”(12)

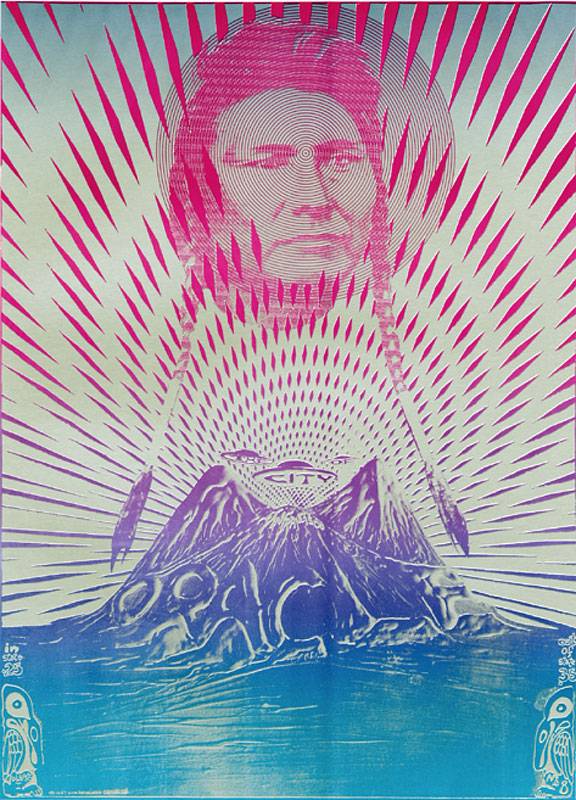

The cover of the “American Indian Tradition” issue of The Oracle, a popular hippie publication. The artwork commodifies indigenous people, a common and hip practice at the time in San Francisco.

Source: The Oracle facsimile edition

1960’s San Franciscans idolized supposed tribal connections to nature or spiritual world — ideas perpetuated in media caricatures of the “stoic Indian.”(12) Drawn to these false assumptions, hippies embraced indigenous people in what Sherry Smith dubs a “long-hair convergence.”(15) Movements like “Back-to-the-Land” encouraged hippies to live like Native people, while at the same time, the government prohibited indigenous people from doing the same.(16) Few hippies, most of whom were white, even sought to learn about true Native lifestyles and values, and many instead formulated their perception of indigenous people based on the caricatured plains Indians depicted in Hollywood — a far cry from diverse, contemporary Native people. Native Americans were not full humans in media but historical snapshots, and many viewers subconsciously accepted this terminal narrative; again and again American Indians were show as an extinct species, not a living people. In such movies, tribes were not illustrated as distinct entities, but as one homogenous “Indian” race. Thus the hippie definition of “Indian” became its own beast, unrecognizable to true indigenous people. The hippie movement celebrated the image of indigenous culture, but the people they sought to honor instead became fetishized commodities — not sentient people.(14)

Littlefeather recalled her first visit to Haight-Ashbury in 1966, where she arrived in native regalia. She said, “People would ask, ‘What are you? Are you a hippie?’ And I would say, ‘No, I’m an Indian. What’s a hippie?’ I went to see what a hippie looked like, and I thought, ‘I don’t look like that!’”(12) Stories like this emphasize how true Native cultures grew invisible because hippie caricatures overshadowed the plight of Native communities. Simon J. Ortiz’s early 70’s story in Kenneth Rosen’s anthology, The Man to Send Rain Clouds, emphasizes this blind fetishization. In the story an elderly Pueblo man travels to San Francisco in search of his lost granddaughter and befriends hippies, who themselves want to be “Indian.” They welcome the elder in hopes that he will teach them how to use peyote, ignoring his search for the child and leaving him helpless.(17) Although indigenous people were almost venerated in the counterculture, this trend of “dressing up as Indian” walked a fine line between admiration and cultural appropriation as indigenous culture was used for profit and social capital.

Activists Push Back

Heavily inspired by the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements of the 1960’s, Native Americans, too, pushed back against the injustices they faced. American Indian Movement, a militant group to protest police discrimination, was founded in July 1969 in Minneapolis, Minnesota — but similar sentiments soon spread to recently resettled indigenous people along the West Coast.(3) Just a year later, United Indians of All Tribes was founded in Seattle to provide social and educational services.(18)

Student activists in San Francisco became heavily involved in the Red Power Movement, which climaxed in the Occupation of Alcatraz. While the first attempt less than two weeks prior was largely ineffective, on November 20, 1969 an inter-tribal group at the San Francisco Indian Center for “Indians Of All Tribes” led a reclaiming of tribal land that would ultimately last 19 months. About 100 activists took back Alcatraz to demand governmental attention on Native issues including healthcare, education, unemployment, religious freedom, the return of ancestral artifacts and burial sites, etc.(3) The full intentions were artfully communicated in their proclamation.(19)

The effort was spearheaded by students — in particular a Native organizers Richard Oakes, a San Francisco State University student, and LaNada Means, a University of California, Berkeley student.(20) Trudell, a Vietnam veteran, served as a spokesperson. His radio show, “Free Alcatraz,” was integral in publicizing the occupation to a national audience.(21) Interestingly, the Ohlone, the tribe native to the region, did not participate because they believed the island was cursed.(3)

The protestors living on Alcatraz where ultimately forced to withdraw due to pressures from the federal government, but the occupation was still impactful.(22) It put the Red Power Movement on the map and sparked subsequent protests — most notably the armed conflict at Wounded Knee on February 27, 1973.(3) The occupation showed the power of the Native community and proved that they would not be taken advantage of.

Legacy and the Continued Fight

Although the Red Power Movement began over about fifty years ago, many of the same issues still exist, and few of the demands given at Alcatraz ever were fulfilled.(19) Nevertheless, the Bay area Native community is still strong despite the fact that populations in the city have been declining since a peak in 2000.(4) One small victory has been the integration of Native culture in university curricula due to the activism of many leaders involved in the Alcatraz occupation. Both SFSU and Cal now have Native American studies programs because of Oakes and Means, respectively.(23)

Inequality is still rampant in San Francisco, however, and debate over the portrayal of indigenous people in the city is still ongoing. Recently, historical monuments and artwork in particular have been called into question for their subjugation of Native people. The city removed one such controversial statue from San Francisco’s civic center just last year.(24) Native activists’ work still continues to reshape the narrative around indigenous people, especially in a city like San Francisco where much of their legacy is distorted or unknown.

Notes

1. "House Concurrent Resolution 108." Digital History. Date Accessed: 25 May 2019

2. “Unforgettable Change: 1960s: American Indians Occupy Alcatraz.” Picture This: California Perspectives on American History, Oakland Museum of California. Accessed: 24 May 2019

3. Hendrix, Levanne R. “1953 to 1969: Policy of Termination and Relocation.” Ethnogeriatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine. Accessed: 22 May 2019

4. “San Francisco Population.” San Francisco History, SFGenealogy. Accessed: 21 May 2019

5. “A History of American Indians in California.” (pdf) Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Accessed: 5 June 2019

6. “American Indian Urban Relocation.” Educator Resources, The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (15 August 2016) Accessed: 25 May 2019

7. “Relocation.” National Council of Urban Indian Health.

8. “Homogenization, Protests & Outright Rebellion: 1950s: Native Americans Move to the City—The Urban Relocation Program.” Picture This: California Perspectives on American History, Oakland Museum of California. Accessed: 24 May 2019

9. Ward, Brian, “1968: The Rise of the Red Power Movement,” Socialist Worker. 8 August 2018. Accessed: 2 June 2019

10. Beyond Recognition. Directed by Michelle Steinberg. Underexposed Films, 2014.

11. Whittle, Joe. “Most Native Americans live in cities, not reservations. Here are their stories,” The Guardian, 4 September 2017. Accessed: 3 June 2019.

12. Reel Injun. Directed by Neil Diamond and Catherine Bainbridge. National Film Board of Canada, 2009.

13. Allen Cohen, “The San Francisco Oracle: A Brief History,” from Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, Part 1, ed. Ken Wachsburger (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011).

14. Lemke-Santangelo, Gretchen. 2009. Daughters of Aquarius: Women of the Sixties Counterculture. Lawrence, Kan: University Press of Kansas.

15. Jawort, Adrian. “Hippies and Indians: Pathway to the Mainstream.” Indian Country Today, (20 August 2012). Accessed: 24 May 2019

16. Hippies Playing Indian. Performed by Lana Richards, Harriet Hilker, and Sherry Smith. Connecticut College, 2016. Accessed May 26, 2019.

17. Allen, Paula Gunn. "All the Good Indians." Social Text, no. 9/10 (1984): 226-29. doi:10.2307/466546.

18. “United Indians.” United Indians of all tribes Foundation, Accessed: 25 May 2019

19. “Alcatraz Proclamation.” Found SF. Accessed: 26 May 2019

20. “Women's History Month Special: Featured Guests.” Empowerment Works, Inc., (21 March 2018) Accessed: 25 May 2019

21. “Biography.” John Trudell. Accessed: 24 May 2019

22. Fortunate Eagle, Adam. “The Indian Occupation of Alcatraz.” Found SF. Accessed: 25 May 2019

23. “Alum Richard Oakes Featured on Google Doodle.” College of Liberal and Creative Arts, San Francisco State University, 22 May 2017, Accessed: 24 May 2019

24. Gold, Michael.“San Francisco Will Remove Controversial Statue of Native American Man,” The New York Times, 7 March 2018, Accessed: 22 May 2019