Yerba Buena Center: Redevelopment and a Working Class Community’s Resistance

Historical Essay

By John Elrick

During the later years of the Depression (1937 in this photo), the Howard Street stretch between 3rd and 4th Streets became labeled as "Skid Row," setting the stage for the conflicts that emerged in the 1960s over redevelopment and building the Moscone Convention Center.

Photo: Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress

Unemployed men pause in front of the Salvation Army, April 1939, near 3rd and Howard.

Photo: Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress

After the passage of the federal Housing Act of 1949, a sea of urban renewal projects swept across the United States. By the mid-sixties supporters of redevelopment in San Francisco had solidified plans to transform an 87-acred plot of land in the South of Market district into the Yerba Buena Center. Standing in the way of the project were some 3000 residential hotel occupants and over 300 families. In 1969, several hundred project-area residents formed Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) in order to resist relocation efforts. During their struggle against the Yerba Buena Center redevelopment project, the members of TOOR expressed their identities as workers and unionists, Democrats and citizens, and as members of an established community.

An examination of the identity articulated by TOOR in relation to urban redevelopment also helps illuminate themes of continuity and change in San Francisco city politics and urban policy. TOOR’s working class roots and union loyalty stood in contrast to organized labor’s shifting stance on the Yerba Buena Center redevelopment project, highlighting San Francisco labor’s long-running adherence to the notion of business-labor cooperation, in particular since the onset of the Cold War. Likewise, an examination of TOOR’s expressed allegiance to the Democratic Party as the party of the working class, coupled with across-the-board political support of the project, exposes the development and solidification of the city’s pro-growth liberalism. Finally, as TOOR came into direct opposition over the issue of redevelopment with the organizations and political institutions its members had closely identified with as workers, the residents’ shared experiences, goals, and socioeconomic standing reinforced their status as community members and ultimately drove their fight against the Yerba Buena Center project. That TOOR came to oppose relocation primarily as a community group, rather than a class-based political organization, foreshadows the emergence of a new progressive movement in the city.

Mars Hotel, 193 4th Street, prior to demolition during Yerba Buena redevelopment, October 1970.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, TOR-0050

Selected Quotations

The Redevelopment of South of Market

Panama Hotel, 176 4th Street, and Mars Hotel, 193 4th Street, before demolition, October 1970.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, TOR-0049

In a 1925 study entitled “The Feasibility of Redevelopment in the South of Market Area,” the Redevelopment Agency expressed concern about “the problems of blight and with ways and means of improving the area through the use of the redevelopment process.”

“Here in San Francisco,” Justin Herman told a Senate Committee on Aging in 1962, “we have a 90-acre area running roughly from Mission Street to the freeway, and perhaps Third Street to midway between Fourth and Fifth Streets . . . well known to San Franciscans as the skid row.” In regards to the district’s “skid row” residents, the director remarked, “If you leave them where they are they deteriorate some of our most valuable areas in the community.”

“Yerba Buena Center is a small part – only 87 acres of South of Market’s 1100,” a tentative proposal for the redevelopment of South of Market stated, “when the 87 acres are freed of blighting influences . . . the economic growth will surely spread to the rest of South of Market.” Before the vision could be put into place, however, the Agency indicated, “individuals, families and businesses must be relocated.”

The Yerba Buena Center’s official citizen participatory organization, the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, released a study entitles “Prologue for Action” which mused, ‘If San Francisco chooses to emphasize its role of central city, and strengthen its academic-intellectual activities as a part of its program to do so, increased education levels for all citizens will result.”

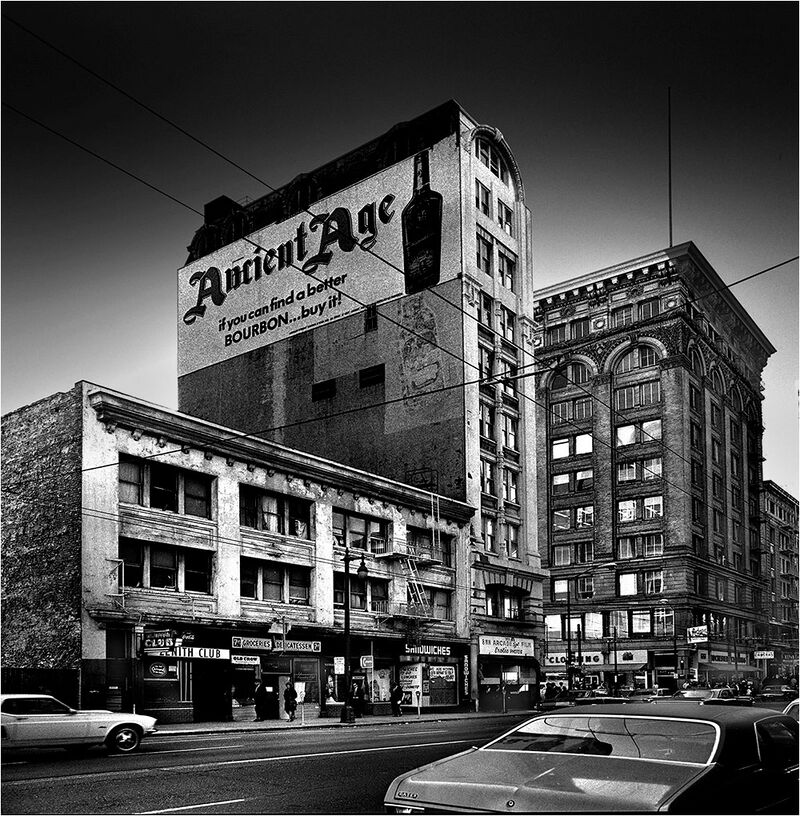

Third and Mission, c. 1968.

Photo: © Ted Kurihara

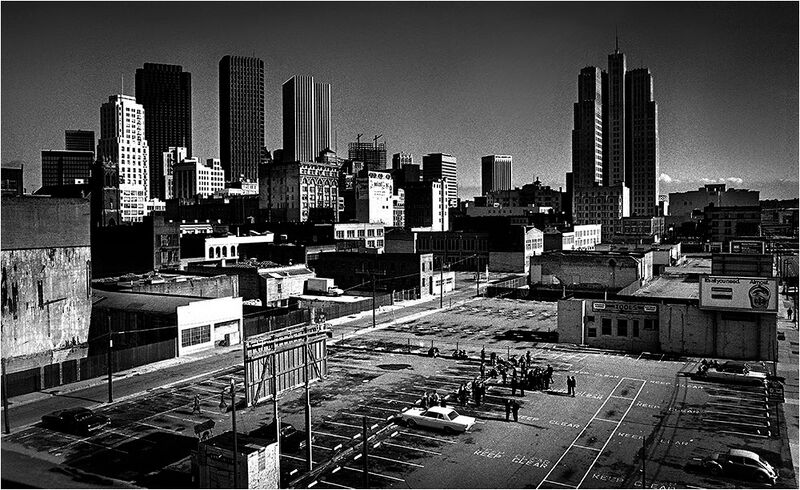

View east down Folsom Street from above 4th Street, 1968. Most of the area has been cleared for parking lots, prior to the underground construction of the Moscone Center.

Photo: © Ted Kurihara

TOOR Members as Workers and Unionists

Eighty year-old Milner Hotel resident Tom Thomas recounted, “I cam from Greece 59 years ago and have lived in the San Francisco area the whole time. I’ve been in all types of businesses – the railroad, the mills, laundry, and I even ran a wine and beer shop nearby.” The thought of leaving his hotel drove Thomas to write, “I don’t know what the hell I will do when I have t o leave. Things are terrible out there.”

David Johnson’s description of this career was representational of many TOOR members: “During the years before I retired, I worked primarily as a seaman and visited most of the ports of the world. I worked as a seaman during the First World War and continued in that type of work.”

In a letter produced by TOOR, the community activists summed up what their collective work history meant: “We have loaded and unloaded cargo on the docks of San Francisco. We have sailed the ships of this country to all the ports of the world. We have driven trucks to Reno, Sal Lake, Chicago, Des Moines, and New York. We have spent our lives keeping this country going.”

The founder and elected chairman of TOOR, eighty year-old Milner Hotel resident George Woolf, began his court affidavit by stating, “I have been active in the labor movement for over fifty years . . . I am still a member of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union.” Woolf helped organize rank and file longshoremen in 1932 and 1933, “took charge” of the Shipscalers’ and Painters’ Union, helped found and organize the Alaska Cannery Workers Union, and was the “California State Chairman of the successful movement to repeal the state Criminal Syndicalism Act.” “I do no want,” Woolf wrote, “to be pushed around and told where I am to live.”

While many TOOR members were retired union members, some were still employed and active in the unions. Thomas Nugent lamented, ”I just can’t see this house being torn down as it affords me very close proximity to my work being only 4 blocks from my work. . . . I am with the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union. In an official capacity.”

Organized Labor and the YBC

In an official bulletin of the San Francisco Labor Council, Secretary George Johns remarked, “skid row and broken bottles are presumably the targets [but] two minority groups, Negro families and the Aged, will be the most prominent victims of a massive eviction. It is no secret that unemployment in San Francisco is much too high. The present version of urban renewal and usual tampering with and elimination of industrial sites will only make it higher.”

San Francisco Labor, the council’s official organ, blasted the project in 1965: “Five thousand jobs or more and thousands of homes are doomed if the city’s Redevelopment Agency turns loose its bulldozers on the proposed 87-acre South of Market Yerba Buena project. As projects develop,” the paper stated,” it becomes obvious that the needs of people became secondary to the interests of speculators.”

When George Johns contested the intent of the original Yerba Buena plan, he also argued, “rehabilitation and conservation programs for Yerba Buena which are compatible with light industrial use would offer employment to workers in both construction and non-construction industries.”

Rather than seeing the city’s business interests as the enemy, though, organized labor remained “convinced that labor-management committee policy making can contribute an effective approach.”

With both rising joblessness and rising prices emerging as “issues for the seventies,” organized labor came to the position that “growth, not economic deterioration, is the way to fight unemployment and inflation.”

A combination of both continuity and change characterized labor’s switch from supporting the Yerba Buena project area residents to referring to the members of TOOR as “skid row residents [who] remain to be moved” in a pamphlet released jointly by the Labor Council, Building Trades Council, and the ILWU.

The Democratic Party and the Liberal Consensus

In a letter addressed to “Fellow Democrats,” TOOR claimed,” We have given our lives in support of our country. We have given you our votes. Will you give us our help?”

"Ever since F.D.R.’s victory in 1932, you have looked after the little people. You have known that little people – people without money or power or influence – are the source of greatness of our country. You have made democracy work in this country, and the little people have rewarded you with their votes.”

By the time TOOR demanded to know “Why, Now, Fellow Democrats Have You Sold Us Out?” the liberal consensus had been developing the city for decades.

During his retirement, George Johns explained, “During Jack Shelley’s time as [Labor Council] secretary, we had reached an understanding with Bill Story of the San Francisco Employers Council. This deal was essentially mutual recognition and a commitment to try to amicably resolve labor-management relations.”

By 1972, when Mayor Alioto addressed a west coast meeting of the ILWU, city leaders had long been able to cast redevelopment as in the interest of both organized labor and society as a whole. “In San Francisco,” Alioto told the union crowd, “we took the position we were going to push construction. To say you can cure inflation by unemployment is moral and economic bankruptcy.”

The Importance of Community

“The Milner Hotel is my home,” stated one resident, “and I enjoy it here with my friends. The people in the hotel are good to me – I do not want to be forced to leave.”

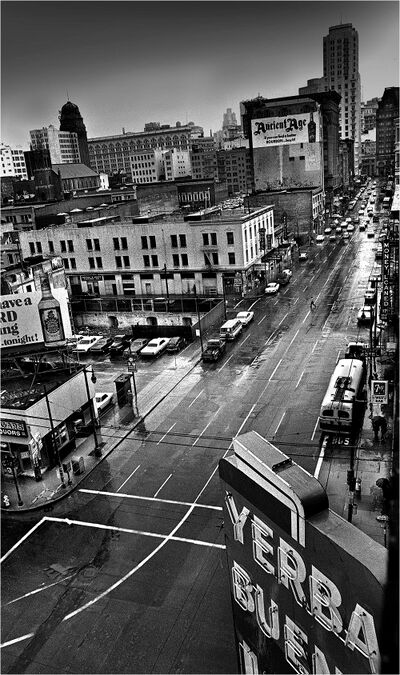

View of 3rd Street looking north from the Yerba Buena Hotel at Howard and 3rd, c. 1968.

Photo: © Ted Kurihara

A resident name Luther Briggs described to the court what the community meant to him: “I have lived in this South of Market district for 30 years. My whole little world and existence and my only friends are here. To be forced out of here would upset my whole existence.”

The Milner Hotel manager, Anne Nichols, referred to the hotel dwellers as “our people” and extrapolated, “They don’t just have a room here. This is their home. If they can’t afford a haircut, I see that someone does it for them free and have even shaved them and reminded them to go back and put their teeth in.”

For project area residents, the battle over the Yerba Buena Center was literally a life or death one, as exemplified by eighty-seven year old George Maurgen’s brief statement to the court: “I would like to die here.”

A decade after TOOR’s legal battle ended, former Chairman Pete Mendelsohn commented, “I still do the same thing I always did. I go around fighting evil wherever I find it.”

Yerba Buena area, c. 1970

Photo: © Ted Kurihara