The Goodman Building: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

''by Martha Senger'' | ''by Martha Senger'' | ||

{{#ev:archive_audio| | {{#ev:archive_audio|MarthaSengerGoodmanBuildingOnArtistsResidentialHotels_64kb|350}} | ||

Revision as of 19:36, 30 March 2009

Historical Essay

by Martha Senger

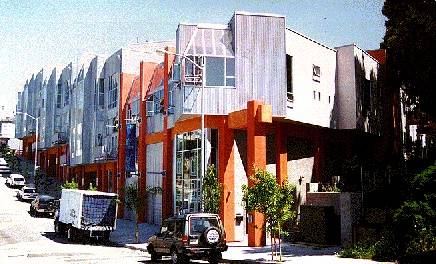

Goodman Bldg. #2 or 'G2'--1996

Photo: Chris Carlsson

File:Housing1$goodman-building-1.jpg

Goodman Bldg. #1, 1996

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In his book The Philosophy of Social Ecology anarchist philosopher Murray Bookchin wrote:

"The terrible tragedy of the present social era is not only that it is polluting the environment but also that it is simplifying natural eco-communities, social relationships, and even the human psyche. The pulverization of the natural world is being followed by the pulverization of the social world and the psychological."

In the growing recognition that the world ecological crisis is rooted in runaway industrialization, which itself is rooted in the reductionist-materialist mindset that established the modern era, various thinkers are looking to pre-modern and tribal cultures for healthier constructs. Constructs whose economies are integral aspects of multidimensional lifestyles. Lifestyles whose rewards are intrinsic rather than extrinsic, with notions of growth that are equated with aesthetic and spiritual satisfactions rather than material expansion. In short, the kind of organic growth that emerges from within, rather than from without.

This is about such a culture, but rather than being distant in time or place, it exists today in our urban midst, although constantly having to reinvent itself as its underground and illegal environments are continually turned to more profitable uses. A cell within the counterculture, it is the artists' living and working cooperative.

Unlike most, the culture I'll talk about had--or I should say seized--a chance to hunker down and really develop, in the true sense of that tragically misused term, and to actualize a potential that few have done before.

I stumbled onto it in a serendipitous way just as I was trying to make sense out of a deeply disturbing experience--several months spent living in the midst of the St. Louis housing projects. I had gone there to visit a friend--a priest and criminologist whose mission was to look for solutions to the violence that pervaded the projects, then as now. I would walk through them with him--endless rows of identical bunkers, interspersed with tiny plots of dead grass, windows and elevators broken, halls with pools of urine, balconies fenced with thick crossed wire. I was shocked and traumatized, both by their inert brutality and by the hopelessness and powerlessness of their residents. People who for the most part hadn't chosen to live there but had been forcibly 'relocated' to the projects when their old neighborhoods had been seized by the local Redevelopment Agency, then gentrified to make profits for favored developers.

That July, the largest of the projects, the Pruitt Igoe, was declared unliveable by the City of St. Louis and demolished. Three city blocks of what had been an internationally acclaimed model of "rational" "functional" design were bombed. Its destruction became a symbol of the death and failure of the modern architectural ideal, the Bauhaus vision of "worker's housing." Corbusier's "machine for living in."

What had gone wrong? Was it the form? Or was it the function? Or, was it both?

That fall I returned to California. But instead of going back to my studio in Big Sur, decided to come to San Francisco in the hope of finding in the midst of its more complex life clues to the social disaster I had seen. And to find a cheap place where I could live and paint.

A friend told me to check out the Goodman Building, an old artists' hotel on Geary Street, but warned I wouldn't be able to stay there long as it was soon to be torn down to make way for a highrise. And so from the start, I was confronted with that which I had sought, a complex situation that furthermore was fraught with contradictions--a highrise office building looming threateningly over an affordable artists' environment, and its being taken for granted that the highrise had some ordained priority to exist and the artists community to disperse.

Whence came this perverse prioritizing of things? In his book The Re-enchantment of Nature Morris Berman writes of its origins:

"For more than 99 percent of human history the world was enchanted and man saw himself as an integral part of it. Throughout the middle ages men and women continued to see the world primarily as a garment they wore rather than a collection of discrete objects they confronted. In the course of the 17th century, western Europe hammered out a new way of perceiving reality. The most important change was the shift from quality to quantity, from 'why' to 'how.' The universe, once seen as alive, possessing its own goals and purposes, is now a collection of inert matter hurrying around endlessly and meaninglessly.

I have argued that science became the integrating mythology of industrial society, and that because of fundamental errors of that epistemology, the whole system is now dysfunctional ... a view of reality structured on what is only conscious and empirical and excluding the tacit knowledge that any perception in fact depends upon, has brought us to an impasse ... some type of holistic, or participating consciousness and a corresponding socio-political formation have to emerge if we are to survive as a species. I have suggested that the split between analysis and affect which characterizes modern science cannot be extended any further without the virtual end of the human race, and that our only hope is a very different sort of integrating mythology."

I suggest that the story of the Goodman Group was such an integral myth. That it was the history of the becoming of an organic feeling and thinking totality; a totality achieved through integrating circuits, or spheres, that have been falsely separated during the modern era. These are 1) the sphere of the deep self and its creations, the integrated living/working sphere; 2) the sphere of the individual within community, and 3) the sphere of that wider self within the world, which became the making of an epic drama. The tap root that kept it all cohered was the Group's collective unconscious, their shared ideas, as it evolved in history.

I will look at the realms as they first presented themselves at the Goodman Building in the early seventies, and as they integrated during the decade of the Group's struggle.

THE LIVE/WORK SPHERE

It was both the depth and seamlessness of life that first struck me when I moved into the Goodman Building. Built in 1869, it was the last of the traditional hotel- type studio buildings left in San Francisco, having been used almost wholly by artists since the late forties when its rents had gone down to match its deteriorating condition. As the last survivor of this low rent, easy access, communal species, it had received many refugees from the famous Montgomery Block and other artists' hotels when they were demolished or converted to more profitable uses.

When I first moved in, some thirty artists and assorted visionaries lived there, including an anthropologist-filmmaker, an architect-astrologer, a Buddhist printmaker, two leaders of the neo-Dada movement, and a quite mad concert pianist on the top floor. Janis Joplin had lived in a small room on the second floor in the early sixties, as had Wes Wilson, who created the first Psychedelic posters in his studio there.

The entire building was intensely alive, and I would sit for hours on the stairs outside my studio, fascinated, watching the action that never ceased day or night. People would emerge from their private spaces to exchange ideas in the hall, the dining room or kitchen, then disappear into another's studio to look at their work or perhaps borrow a piece of equipment or get advice on some technique. Invariably they'd be given some information or opportunity they had been seeking though perhaps not consciously. The walls of the small second floor bathroom were a wild & crazy graffiti gallery where credos were daily announced and elaborated.

There was no line whatsoever between living and working, and the building's interior forms were as varied and fluid as this uninterrupted functioning. Dark, winding passages opened onto large spaces flooded with light, the intensely private onto spontaneous gatherings. It was a magic, thoroughly psychic structure, intricately interconnected and virtually unencumbered with obstructing regulations or nonessential activities to clog the circuits, the patterns, of the deep neural flow.

This labyrinthian and mysterious character came partly from the Goodman's original design, but even more as the result of the many remodelings that had been done to accommodate its changing history of use. Originally built in 1869 as twin Victorian townhouses, it had survived the earthquake and, because of the housing shortage that followed, was remodeled into a residential hotel, interspersed with offices. What had once been a top floor ballroom was converted to a photographer's studio with a spectacular La Boheme skylight . Then, around 1904, the whole thing was raised up and five storefronts added at the ground floor. Gold was rumored to be hidden in the stairway newel posts and we would hunt for it at parties. A skeleton was reported to be buried under the fallen, defunct elevator. And the ghost of the first owner's wife was said to walk the top floor late at night.

Having spent my first forty plus years in a nuclear, hierarchical family structure where my art-working life and studio were both physically and psychically partitioned from my 'living' life, the integrated flow of the Goodman Building was mind blowing. The contrast with the pathologically restricted functioning of the St. Louis housing projects was even more startling and, for me, deeply and permanently radicalizing.

This way of being of the urban artist, combining living and working under one roof, stems from the economic need to spend as little as possible on rent so as to leave as much time as possible to do art work, which is notoriously poorly paid. It also accommodates the creative continuum that knows no spatial or temporal separation. Functionally, it is that continuum that the artist-creator houses, along with the tools required to materialize it. There is a conspicuous lack of consumption of anything other than pure, unmediated experience. Thus live work space, particularly congregate use live-work space, is the original 'more with less' structure--housing more meaning and community with very little mass. A structure of uniquely frugal fecundity.

It will be my overriding thesis that it is the breaking apart of this continuum, this vital green link, that ultimately resulted in the breaking apart of all the other realms. The continuity of the creation or production process which to thinkers as diverse as Marx and Heidegger constitutes the very essence of human being-ness--the form that being takes in the world--and thus the ontological ground of life.

This process--this connection between the producer and produced, the in-former and the formed--was disastrously and traumatically breached by the industrial revolution. Lewis Mumford wrote in The Culture of Cities that prior to the industrial revolution, "there were no walls, visual or functional, between business, domesticity and education", and cautions in the strongest way, "a deliberate attempt must be made to reunite these aspects of life." But it was Marx to my mind who made the most poignant assessment of this cleavage when he stated that alienation itself began when the worker's "free labor"--his "free movement in matter"--was stolen from him by being turned into a commodity, causing the commodity to magically assume the character of a fetish. Which in turned changed what had been the relationship between persons into a relation between things.

We opened the building's five storefronts and turned them into galleries; a print and graphic workshop, classrooms and rehearsal spaces, and a theatre that over the years spawned several new companies, including Theatre Workers, The Next Stage, Theatre Rhinoceros, and the Lorraine Hansberrry Theatre. We held summer workshops with free classes for children in the neighborhood, and I remember a week long, all building institute for students from a high school in Marin, with classes in acting, maskmaking, painting and printmaking, and one in aesthetics which I taught. Nick wrote and directed and Tom Heinz filmed "The Payment of Teresa Videla" in the building using all resident actors.

Resident painters, sculptors, actors and writers worked on other productions in the theatre, making sets, doing lighting and scriptwriting. The building had become an electrical event generator, pouring out an incredible stream of events, concerts, and experimental work. Plus, the whole time we were creating complex strategies for saving the building, which I'll talk more about later. Also, people's individual work flourished at an unprecedented level throughout all this with the ongoing support of the Group which, unbelievably, met every Monday night for ten years! It was this that kept the whole thing sane and centered through an incredible number and variety of activities and changes. It was the Group that provided the self-ordering of our experimental chaos. It was the meaning vortex that sorted through and analyzed the total flow as it happened, integrating what people felt should be kept and discarding what didn't fit or work, and then imagining and planning what should be undertaken next. It was participatory democracy at its most intense and inspirational--new ideas and solutions and forms pouring in and out in an astonishing and coherent flow. This ongoing feedback and dialogue created a level of cooperation and coordination that raised the level of life there and changed its feel. I often felt part of an almost frictionless flow that was like descriptions I've read of superconductors. We had made a shift to phase space.

Sartre was fascinated by this phenomenon. He wrote,

"A group is an enterprise in a constant movement of integration. The fusion of the group is in fact the invention of each, in a spiral dialectical movement of synthesis upon synthesis. The unity of this fused group is in the interior of each synthesis. In this fused praxis there is the resurrection of freedom. This new total, this fusion of unity and plurality is not an easy operation to describe."

Lucien Goldmann writes similarly that "the group is born of the actions which it generates." Goldmann sees the group as a new plural--or what he calls trans-individual--subject. Its unity is achieved, as anarchist philosophers have always understood, not with a loss of individual freedom, but with the great enhancement of freedom and opportunity that the self activity of an affinity group makes possible.

Our struggle had begun to protect an environment that erected no walls between our individual lives and work. In 'owning' and managing that world, we had broken through another barrier and discovered our own unity and power, a wider identity, and an exhilarating new sense of freedom. . . .

With [a] radical sense of our situation, several of us took the threat of eviction as a call to dialogue, to respond to a deadened world with our organic idea--with a refusal to move that was also an affirmation of a different way of being.

Once the dialogue began, moreover, we found ourselves joined by dozens, that quickly grew to hundreds of helpers, eager to give our different scenario a chance; becoming part of us and adding knowledge and skills we needed but didn't have. This was the beginning of immersion in a tide of synchronistic responses that seemed to answer our every need and move in totally unplanned and unexpected ways. We seemed in sync with an unseen partner, like electrons whose movements, as physicist David Bohm claims, are coordinated by information carried by the wave function. A Neighborhood Legal Assistance attorney, Pam Dostal, built our legal defense based on our right to equal or better housing than we were being forced to give up. Thus we demanded to be relocated to a building where we could legally both live and work. And also to be relocated as a group, because our exchanges and interaction were such a necessary condition for producing our work.

It was a precedent setting case for wholeness. We eventually lost but not until we had taken it all the way to the State Supreme Court, arguing it on the basis of our first amendment right to assemble. Thus it was not just a precedent for congregate, live/work relocation and general consciousness raising, but valuable in giving us protected time to pursue other strategies.

To respond to the Agency's claim that the building was of no value and not worth saving, we undertook a two-year campaign to get it declared a City Landmark, researching its history and architecture with the help of architect and historic preservationist John Campbell who literally gave months of his life to the struggle. We succeeded, and despite furious opposition from the Redevelopment Agency, had the Landmark's Boards vote affirmed by the Board of Supervisors, most of whom made it clear they were supporting the designation not because of the building's architectural significance but because of its use by artists and the special value of that. I remember one said in voting, "this building is alive."

But since that designation only gave the building a limited stay of execution pending needed repairs, we also mounted a successful campaign to get it listed on the National Register of Historic Places which made it eligible for rehabilitation grants. Brad Paul, a photographer who had just moved into the building and begun work for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, pulled it off with great style and skill, knowing the preservation ropes. He later became the first president of our development corporation, leaving the board when Mayor Agnos named him Deputy Mayor for Housing. We began applying for and receiving grants to repair the building from the State Office of Historic Preservation, but as fast as we'd receive them, the Agency would send them back saying they were only a drop in the bucket of the amount needed to bring it to code. And besides, they'd say, we didn't own the building and probably never would. Through newspaper accounts of this obvious oppression, the public got a highly publicized account of the dirty tricks the Agency routinely played with the communities it destroyed in the name of urban renewal.

To show it was feasible to save the building, we got a $10,000 grant from the NEA and did a feasibility analysis, hiring an architectural firm and team of economists who put strategies together to buy the building and pay for its rehab. The study showed definitively that it was feasible to do all this if we pursued a low cost, low impact rehabilitation to bring the building to code as a residential hotel.

Then we formed a nonprofit development corporation, which we called GOODCO, that put these strategies together in an offer and presented it to the Agency. Our plan was supported by the State Housing Office, the State Architect, and the State Office of Appropriate Technology who all praised its economic and energy efficiency in providing both housing and work opportunities for thirty plus people in so little space with such frugal use of resources. It was a more-with-less prototype.

But needless to say, Redevelopment refused our offer, claiming that a residential hotel rehab didn't fit their standards that demanded individual self-contained 'units' each with its own kitchen and bath! A sad and dispiriting example of the power of bureaucracy to atomize community and disallow alternative kinds of development. But through it all, the press wrote and the City watched--and learned. In a letter to the Redevelopment Agency, SF Chronicle architectural critic Allan Temko wrote:

"Now that the building is to be saved, are we to lose everything we fought for?"

By the time of our eviction in 1983when the building was given over to a hugely wasteful development that took five million dollars in what little was then left of Section 8 subsidies to convert a lean and lively congregate use structure into an overblown, inert structure replete with individual baths and kitchens to meet HUD codes and reap huge profits for the developer who cashed in on our preservation efforts and attendant tax write-offs--a lot of consciousness had been raised and our ideas validated, even though we lost the building.

In our spiraling ten-year drama, we had responded, step by step, to the Agency's offers of parts and pieces with a totalizing solution, bootstrapped through our own shared consciousness, in the making of a whole, integral environment.

We had engaged the world and brought a measure of holistic ordering into a corner of mechanized waste and chaos. And along the way, reintroduced a dialectical tension between the poles of vision and matter; taken a step toward deconstructing the divides put up by Descartes and company and done it on the home planet, not outer space.

Our eviction press conference was a sad but mythic event, held in the theatre that the Group had converted from a trash filled storefront ten years before. The press recorded sardonic statements by Margo St. James, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and a relieved Sheriff Mike Hennessy, whose troops had been gathered a few blocks away the day before. Don Terner, Director of the State Housing Office, who had once been a member of the GOODCO Board, said to the press,

"This is craziness--you are watching madness."

And the San Francisco Mime Troupe drummed a dirge that echoed throughout the building and the City.

We had lost the Goodman Building but our idea was still very much alive. And because of all the very visible support, we were able to take with us a half million dollars that had been allocated to our development proposal by the State and City before Redevelopment and its outside developer won.

Jacques Derrida wrote "history releases the transcendent," echoing Hegel, coming alive again in all the movements from below stirring throughout the world, seeking liberation and new forms.

With our idea carrying us, we began the search for another building. And changed our name from GOODCO to ARTSDECO, the Artspace Development Corporation.

A nucleus of hard working true believers have carried on, now led by Steve Taber, an attorney who is also an expert in housing law and finance, and several other ardent live-work advocates. A small but critical mass of synchronized talents with a shared vision, persistently doing what Hegel called "the long and patient work of the negative"--to deconstruct the positivist death grip and reconstruct what we lost.

from Cohering Chaos: Restructuring From Below In The Inner City by Martha Senger

{{#ev:archive_audio|MarthaSengerGoodmanBuildingOnArtistsResidentialHotels_64kb|350}}