Sixth Street

Historical Essay

"I was there..."

by Mark Ellinger

Sixth and Minna, 18 April 1906.

Photo: Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

After the earthquake and fire of 1906, San Francisco’s Sixth Street was rebuilt with rooming houses and residential hotels—also known as SROs, or single room occupancy hotels—that for many decades housed the working class. These days, Sixth Street is where the poor are warehoused and the neighborhood’s working class origins are largely forgotten. As poverty is for many people an uncomfortable truth to be avoided, there are prejudicial blind spots in the general consensus regarding Sixth Street. In fact, most people wish Sixth Street would just go away.

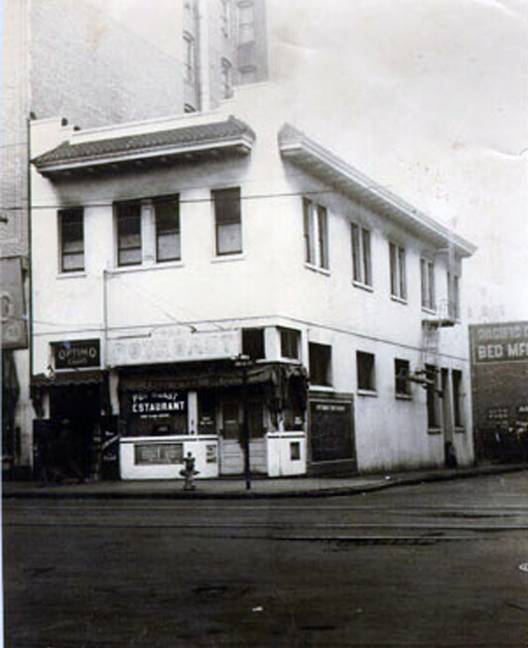

Pot Roast Restaurant, 1927. Long ago demolished, the Pot Roast was a Prohibition era speakeasy on the corner of Sixth and Jessie, next to the Hillsdale Hotel.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Daily life on Sixth Street has been documented since 1992 by the staff and students of the Sixth Street Photography Workshop, and some moving portraits of neighborhood residents comprise a chapter of the book Many Voices* by documentary photographer Virginia Allyn. I began my own portrait of Sixth Street by documenting its architecture and signs. By getting involved in the neighborhood, I got to know the people who live and work there. By listening to their stories, I learned some history. I got involved with the neighborhood by living in it.

*2005, Trafford Books.

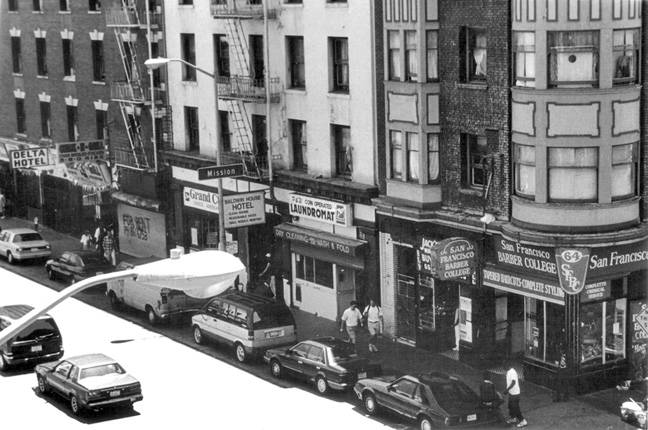

Sixth and Jessie, 1995. On the right is the Shree Ganeshai Hotel, and in the upper right corner are the three turret windows to my old room, #10.

Photo: Virginia Allyn

In mid-Spring 2001, I felt like the luckiest man alive when, with little more than the clothes on my back and a 690 dollar monthly income from State Disability Insurance (SDI), I moved into the Shree Ganeshai Hotel on the corner of Sixth and Jessie. From the moment I became a tenant until the day I moved out, that hotel was home, my sanctum; the world wherein I reinvented myself and the fundament in which Up from the Deep was sprouted. The seed was a cheap digital camera that I rescued from the trash.

"Conveniently Located"

Midtown Loans, 39 Sixth Street.

Whitaker Hotel, 41 Sixth Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

When I immigrated to San Francisco in 1968, the South of Market area was a working class neighborhood largely populated by laborers, off-season migrant workers, merchant marines, and retirees eking out their golden years on meager pensions; men whose sweat and toil helped make San Francisco a thriving, prosperous, world-renowned city. I soon discovered that most people thought of these men as bums and winos, characterizations that had been cultivated since the mid-50s by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency and downtown developers, instigated by hotelier and real estate mogul Ben Swig and promulgated by the San Francisco Chronicle and News Call-Bulletin, two of the City’s daily newspapers.

Newscopy: “Alcoholics on Skid Road.”(SF News Call-Bulletin photo, 1956)

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Following World War Two, the densest concentration of South of Market SROs was in the area known as Yerba Buena, just across Market Street from San Francisco’s business and shopping district. To Ben Swig, Yerba Buena was prime real estate for the expansion of commercial and civic functions. Realizing that the most expeditious way of clearing the area would be to have it declared blighted, he donated money to the redevelopment agency in 1954 for the preparation of a study. Even though the money was returned by agency director and future mayor Joseph Alioto, the plan moved forward.

Newscopy: “Men gathered on Skid Road.” (SF News Call-Bulletin photo, 1956) Look closely at the faces and attire of the men in this photograph and you will see that these same gentlemen were also posed in the next photo.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

In a campaign to discredit the neighborhood’s residents, the newspapers published articles that depicted South of Market SROs as flophouses inhabited by alcoholics and lowlifes, embellishing the stories by posing unwitting hotel residents in photos that purported to show them getting drunk on the sidewalks.

Newscopy: “SKID ROAD, SAN FRANCISCO–’No one along Skid Road is likely to shop carefully.’” (SF News Call-Bulletin photo, 1956)

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Little mention was made of the workers and retirees who were by far the majority of SRO residents. The intention was to mitigate concern for the thousands of people who were to be displaced by the razing of every SRO from Third Street to Fifth Street, thus allowing the City to save millions of dollars by sidestepping the issue of relocation. Who would care about the evictions of bums and ne’er-do-wells?

Newscopy: “SKID ROAD–This is a hotel in the wino district. It has 200 rooms renting from 50 to 75¢ a night, chiefly to old-age pensioners.” (SF News Call-Bulletin photo, 1954)

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

In 1969, many of those who would be affected joined together to form Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR), which took the City to court. After a grim and protracted battle during which people were killed, buildings burned, and political organizations suppressed, the City was forced to provide a modicum of relocation support and to build a couple of residential facilities for seniors before the area was completely gutted. Be that as it may, the cynical manipulation of public opinion successfully engendered a prejudice against hotel life that to this day shapes the common perception of Sixth Street.

Newscopy: “Slum area hotel at 259 Sixth St., owned by William H. H. Davis, president of the City Board of Permit Appeals.” (SF News Call-Bulletin photo by Sid Tate, 1961)

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

In recent years a sympathetic district supervisor helped to implement some needed improvements for the SROs that remain, but otherwise the policies of city government and law enforcement have created more problems than they have solved. As if filthy sidewalks and poorly maintained hotels with greedy owners and abusive managers were not bad enough, residents must also live with the continual threats of robbery and violence, because the police for years have used Sixth Street as a containment zone for crime. The corralling of criminal activity by the San Francisco Police Department and irregular, substandard maintenance by the Department of Public Works are underlying reasons why attempts to improve the appearance of the neighborhood never seem to make any lasting difference.

"Winter Evening, Sixth Street"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

Hotels that have been bought and refurbished by nonprofit housing corporations now have modern, better-maintained accommodations, a major improvement to be sure; but a system of tiered management tends to circumvent meaningful dialog with tenants who have valid complaints, and so-called supportive housing too often fails the very tenants who are least able to care for themselves. Ideally, supportive housing helps people with disabilities live independently by providing individualized services, including medical and psychiatric care, medication and appointment reminders, in-home healthcare assistance, addiction treatment, housekeeping, meal programs, and life coaching. In reality, what some nonprofits call supportive housing is little more than an administrative hierarchy of case managers who refer tenants to outside government and nonprofit service providers. Overwhelmed by sheer numbers and often lacking professional training and experience, such case managers have little time to spend with individual clients. Without on-site personal assistance and followup, some disabled tenants fall through the cracks. Unable to navigate their problems by themselves, they wind up in institutions or on the streets again.

Then there are the City’s master lease hotels, where crimes committed by staff and management — including embezzlement, drug dealing, property theft, pandering, rape and other forms of violent assault — are disturbingly pervasive yet receive little public attention, largely because victims are persuaded to settle out of court. Prominent among master lease hotels is the Seneca on Sixth Street; in essence a government-funded crack house, notorious for violence and open drug activity in the hallways.

Sixth Street, circa 1950.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

I have great love for Sixth Street, not for what it has become, but for what lies beneath the veneer of crime and decay, invisible to all except those who live and work there: its people and its history. Much of what I have learned comes from the stories of old-timers who have lived and worked on Sixth Street for many years. I also have the experience of living in a Sixth Street hotel for nearly six years, and personal memories that span the years since my landing in San Francisco. In all the extensive Bay Area photo archives, there are decidedly few historical images of Sixth Street, but my own photography will some day add a bit more to the record. Even though my portrait of Sixth Street is largely an expression of love, it is also an act of defiance whereby I call down the despoilers of individual lives and thumb my nose at the relentlessly onrushing forces of urbanization and redevelopment, which have no use for history.

"Sai"

Sai Hotel, 964 Howard Street

Photo: Mark Ellinger

Near the middle of February 2001 — one week out of the hospital and just beginning to recover from a six year nightmare of homelessness and heroin addiction — I rented lodgings at the Sai Hotel for 400 dollars a month.* As this was well below what other SROs were charging, it seemed like a bargain until I actually saw what I had rented. On the top floor at the back of the building, an undersized door opened inward on a room so absurdly small, it barely qualified as a crib. The bit of floorspace unoccupied by a single-width bed was a narrow strip along the length of the room, but this was mostly taken up by a small sink and a nightstand. All that remained empty was clearance for the door. To open or close the door from inside the room, I had no choice but to stand on the bed. Every time I shaved or washed my face, I risked electrocution by the ungrounded electrical outlet in an open utility box over the sink. For all practical purposes inaccessible, the lead-colored walls were entirely bare. A diminutive window above the nightstand provided meager illumination that barely dispelled the gloom. Suspended by a length of ancient cloth-insulated wire, a naked sixty-watt light bulb offered more light, but I rarely used it as the glare was intolerable. Every aspect of the room was uncomfortable and oppressive. It felt like a broom closet, in fact I think it had been one, but it was the first place I could call home after nearly six years on the streets.

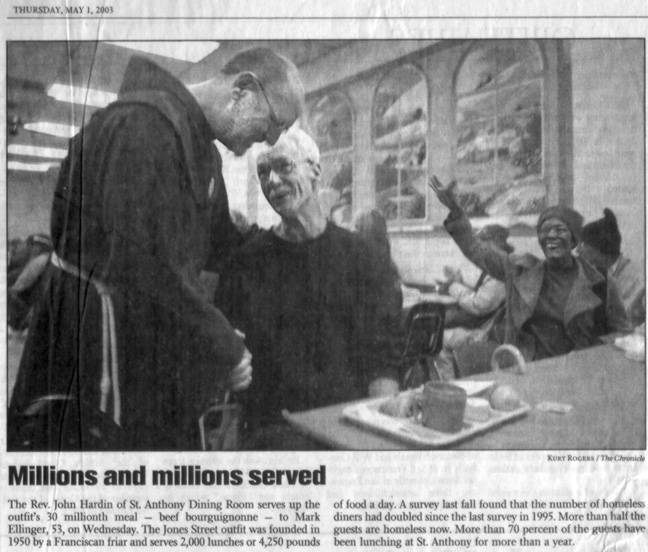

Surviving on 690 dollars a month was a constant struggle. For a long time, my one daily meal was lunch at St. Anthony’s Dining Room.

San Francisco Chronicle, 01 May 2003

Even though I was grateful to have it, my room was far too cheerless and confining to be more than a place to rest my head, so I spent very little time actually living at the Sai. It would be many months before my surgical wounds were more or less healed. Between thrice-weekly visits to the hospital wound clinic, I occupied much of my time reading and writing at the Main Public Library on Grove Street. Lunch at St. Anthony’s Dining Room was my daily bread. An acquaintance one day introduced me to his friend Jozsef, who invited us to tea in his room at the Shree Ganeshai Hotel. Jozsef was an artisan and house-painter who had fled from Hungary during the turmoil of 1989. We discovered in each other common sympathies shaped by hardship and our dialog filled a mutual need for intellectual stimulation. I was soon enjoying regular visits to Jozsef’s snug and homey room, where he had been living for several years. The Shree Ganeshai Hotel was small, quiet and affordable,* and management rented only to long-term tenants. It seemed ideal, and with Jozsef’s endorsement, the manager agreed to let me rent the next available room. I could only hope it would be soon.

*Monthly rent would be 520 dollars, leaving me 170 dollars on which to live.

"Fairfax"

Hotel Fairfax. 420 Eddy Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

Having lived a month in a dismal crib at the Sai, I was more than ready for a change, but the only vacancy I could find was a room at the Hotel Fairfax, a haven for heroin-addicted hustlers, prostitutes and crackheads. Peace and quiet were the rarest of commodities at the Fairfax. Management rarely ventured beyond their first-floor enclave, and hotel housekeeping was spotty and superficial at best. The upstairs bathrooms and toilets were unspeakably vile. For the most part, tenants were free to carry on however they pleased in shadowy hallways and on dark, winding stairs at all hours of the day and night. In need of a temporary hideout or a bathroom, or for reasons best left undiscovered, all kinds of unsavory characters would lurk about the upper floors late at night after sneaking up the rear fire escape. In the end, five weeks at the Fairfax was all I could stand.

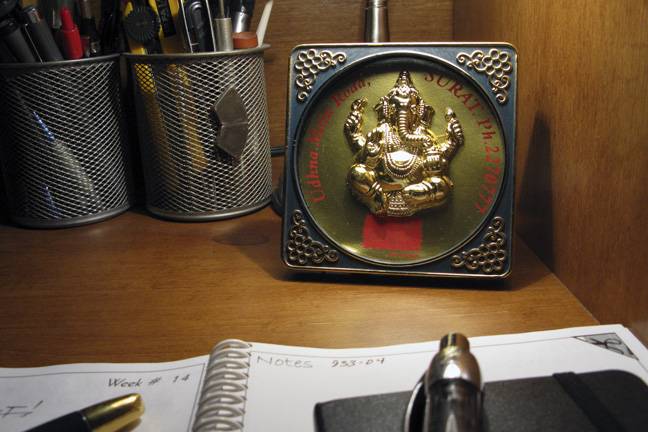

"Invocation"

Shree Ganeshai Hotel, 68 Sixth Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

For the next few weeks, I slept sitting upright in bus shelters. At last in mid-May, I took possession of a room at the Shree Ganeshai. The title of the photo “Invocation” is derived from the name of the hotel. Many centuries ago, Sanskrit scholars began their writings with an invocation to God, usually the one their family worshiped. One such invocation, to Ganesha,* was shree ganeshaya namah. Over time the invocation came to be used before starting any activity and was gradually shortened until shree ganesh sufficed as a prayer for an auspicious beginning. The phrase is used today before any beginning, be it a meal, a journey, or a task. During my stay at the Shree Ganeshai, it was comforting to know that the name of my home was an endless prayer to Ganesha for a bright and beneficent new beginning. To this day I keep on my bookshelf a small golden effigy of Ganesha, a gift from the Shree Ganeshai’s manager, Nagin.

*In the Hindu pantheon, Ganesha is the elephant-headed god of wisdom and auspicious beginnings, who brought writing to the world by breaking off one of his tusks to use as a pen.'

"Ganesha"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

A view from my old room.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

A view from Room #10.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

A corner of my room.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

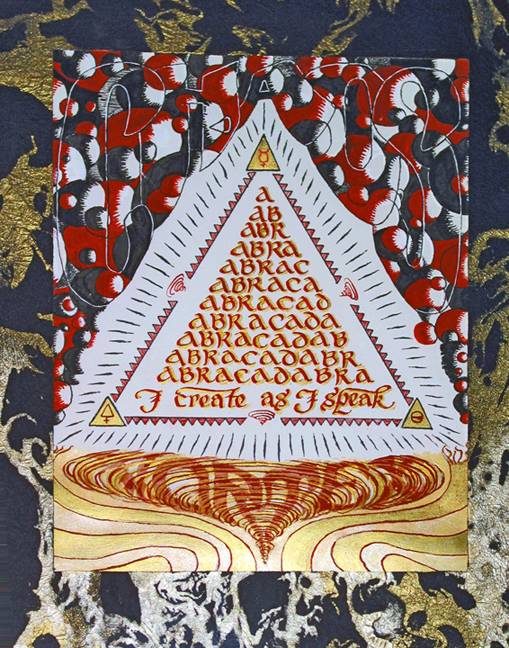

"abracadabra"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

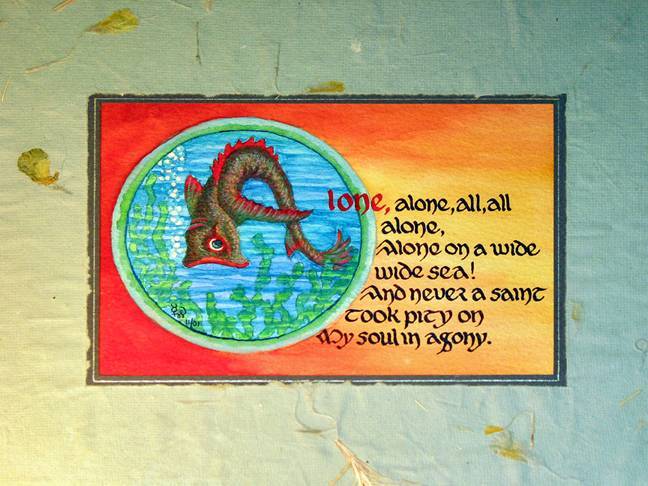

Reinventing myself meant foremost, rebuilding my sense of self by recovering memories of who I had been before life as a homeless junkie had annihilated my self-image; that, and reactivating parts of my brain that had fallen dormant during that time. To accomplish this, I used writing, drawing, painting and calligraphy as my primary tools. Above is the first of my pen-and-ink drawings, dated July 2001, my third month at the Shree Ganeshai Hotel. While hospitalized, I had rediscovered my love of language and symbolism when I read Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. Soon afterward, I started a journal and sketchbook. Once I had established myself at the Shree Ganeshai, I began poring over alchemical treatises and ars combinatoria of the Middle Ages, wherein I found the inspiration for many of my drawings, including “abracadabra.” Below, dated November 2001, is the first of three watercolor decorated letters that paid homage to poets whose writings had inspired me in years gone by. Near the end of 2002, after acquiring a castoff plastic camera, I began photographing my surroundings.

"Alone" (Stanza from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge)

Photo: Mark Ellinger

"Dawn – Rain's End"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

As an insomniac, I have seen many beautiful sunrises. I captured this one while seated at my computer one spring morning after a night of heavy rain. On the left is a corner of the Hillsdale Hotel. The stacks are part of a PG and E steam plant on Jessie Street. This particular view resonated very deeply with me, and the reasons for this are to be found in my childhood.

"Gray Day #3"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

I grew up in a Midwestern city in the 1950s, before urban renewal, corporatism, and the “form follows function” aesthetic of postmodern and corporate modernist architecture eviscerated much of this country’s soul. Grandpa “PR” Ellinger was a brakeman for the B and O Railroad. Some of my earliest memories are of freight trains being assembled in the yards by 0-8-0 switching engines, and of giant 4-8-2 locomotives waiting by the pit or in the roundhouse. Everywhere were the smells of coal smoke, oil and hot metal, and the sounds of herculean iron machines at work: a crashing and hissing of superheated steam punctuated by whistle blasts that telegraphed the movements of the trains.

"Island Out of Time"

Hillsdale Hotel, 51 Sixth Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

My other grandfather, “Red” Tobin, was a chemist for the city water purification plant, built circa 1912. When I was a boy, the plant’s enormous machinery, valves, pipes, filtration pools and conduits were still original, as were the many brass-handled controls and oversize gauges. Everything was perfectly maintained and housed in cavernous structures of iron and brick. All of this filled me with wonder and I idolized Grandpa Tobin, so at times when he had to check plant operations, I would beg him to take me along. Each time he would walk me throughout the enormous facility, patiently explaining everything in great detail. Most wondrous of all was the pump house, a brick building five stories high and three stories deep that had brass-railed ironwork galleries instead of floors, and walls that were lined with banks of indicator lights and old-fashioned recording gauges—all built around the colossal, steam-driven, Corliss flywheel pumps that fed the city’s water supply. Such are the archetypes that inform my world view.

"Hillsdale"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

It should therefore come as no surprise that I find poignant beauty in buildings most people regard as lowly, squalid eyesores. These old hotels have an archetypal quality that stirs my blood and attracts me like a magnet. So many people, so many stories, so much living has taken place within their walls. How can you not feel it? We are far too willing to dispose of anything that is old just because we are told that new things are somehow better. I would ask why we are being told this. Who benefits when we are divested of our history and culture?

"My Back Yard"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

The closest building in this photo is the Lawrence Hotel. Behind it is the Hotel Seneca, where windows to inner worlds glow as evening falls. The rear wall of Fascination can be seen peeking over the roof line of the Lawrence where it intersects with the edge of the Seneca. Between the Seneca and the McAllister Tower in the background is black-iron framework that once supported a water tank. Many of the older buildings in San Francisco have still-functioning rooftop water tanks, built in response to the 1906 conflagration that was catalyzed by earthquake-shattered water mains.

"Dentils of Metal"

Sunnyside Hotel, 135 Sixth Street.

Minna Lee Hotel, 149 Sixth Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

In Classical architecture, the repeating, box-shaped components of a cornice are called dentils. While their size and details vary, they are always symmetrical and look like rows of evenly spaced teeth, whence their name was derived.

"A Lost Art"

Sunset Hotel, 161 Sixth Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

Shown here is a small section of the cornice that crowns the Sunset Hotel. I like it for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the simplicity of its design. I also like the very large dentils and the medallion that decorates the bracket at the end. Rust reveals metal beneath the illusion of carved stone. Simplicity and neglect combine to make this architectural detail a perfect symbol for all old residential hotels.

"If Walls Could Speak"

Hugo Hotel, 200 Sixth Street.

Photo: Mark Ellinger

The Hugo was Sixth Street’s oldest hotel. Shuttered and vacant after a fire burned out several rooms in 1987, the unreinforced masonry building also suffered structural damage in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. In 1997 a group of artists led by Brian Goggin transformed the Hugo into an immense sculptural mural called "Defenestration." Scavenged furniture and appliances were modified by the artists to make them appear animate and then cleverly affixed to the hotel. Tables and chairs leapt from the roof and ran across the walls. Lamps corkscrewed from some windows, and sofas, refrigerators, bathtubs, even a grandfather clock squirmed and leapt from others. Sightseers took untold thousands of photographs of the Hugo and its famous furniture; a housing crisis turned into public art. I photographed the Hugo’s former service alley because it showed the only wall of the hotel that had not been altered, save by the hand of Time.

"Defenestration"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

"Defenestration" endured for nearly eighteen years, although most of the original sideshow-themed paintings disappeared beneath eye-popping murals of polychrome street art. As a work of conceptual art, the Hugo Hotel was universally appealing — everyone liked it — and I grew more attached to it with each passing year. Yet few people know the hotel remained empty for almost thirty years because its owners cared more about profits than people. They refused to repair and maintain the building as low income housing, but were unable to sell it because their asking price vastly exceeded the building’s actual market value. Their outspoken contempt* for those less fortunate reflects an attitude that for years has been tacitly encouraged by the policies of local government. After years of haggling with the owners, in January 2008 the redevelopment agency announced it was seizing the Hugo by eminent domain, foredooming the controversial landmark to demolition.

*”They can put the low-income people somewhere else… you can be homeless somewhere in Idaho.” — Varsha Patel, former owner, Hugo Hotel.

"Daybreak – Hugo Hotel"

Photo: Mark Ellinger

As embodied by the new Yerba Buena pavilions, galleries, malls and tourist hotels, and a widespread proliferation of drab and overbearing condominiums, modern urbanism has been steadily taking over the South of Market landscape for several decades. Demolished, plowed under and built over, the old “South of the Slot” district has been fragmented into near-oblivion, and Sixth Street for years has been slowly dying by attrition. The Hugo Hotel was at last razed in mid-Spring 2015. Inasmuch as it helped prevent the total dissolution of the old neighborhood by holding off encroaching urbanization and gentrification, the transformation of Sixth Street will no doubt proceed in earnest now that the hotel is gone. Despite its longtime closure in the face of a housing shortage, the Hugo was given new life and purpose by the artists who created "Defenestration." Transformed, the old hotel was a kind of signpost: a reminder of the past and a symbol of the present. It was a powerful presence that will not soon be forgotten.